Nordling here.

This gets personal.

I was 22 in September, 1991. I lived alone, in a one-bedroom apartment in Houston right outside of the parking lot of a mega-supermarket in the southwest side. My apartment was a complete shambles – most of the time I didn’t even have lights because I couldn’t afford them with the meager paycheck I had from my job. I had enough for rent, some chicken burritos I’d get at Taco Bell, and what I didn’t spend on bus money, I spent on CDs or going to the movies. My CD player was surgically attached to my hip, because all I really had was music. When I had enough money to go to the movies, I’d go. Sometimes with friends, who had no idea of the depression and the desperation I was living through. Maybe they knew. But they never really said anything.

My father died four years before, and a year after that, I was living on my own. I was so depressed, I think, that I didn’t even truly know what the word meant. I thought of suicide, but I was too scared and too Catholic to do anything about it. A year before, I was in a relationship – if it could really be called that – that ended badly for me. I read more into it than she did. My mom was seeing her first husband again, and that also ended in cancer. The family that I knew was destroyed, and I embraced my friends in a way that was probably off-putting to them. Maybe they knew how bad I was. But I never said anything either.

Still, the movies, the music. R.E.M., the Pixies, Sonic Youth, Fugazi. I was pissed off, rejected, and only in the darkness of a movie theater, or in my apartment, headphones on, did I feel truly free. I bought Nirvana’s NEVERMIND the week it came out. All the music critics I read, who had gotten the CD weeks before, said it was a must-buy, that it changed everything. I’d heard “Smells Like Teen Spirit” already on the radio, during one of those interludes when I had power in my apartment, and hearing those chords knocked me for a loop. I remember the first time I heard that song almost perfectly. Nothing was the same.

Nirvana didn’t save my life. They just reminded me that I still had one, that I could do anything I wanted with it. That there were people who did care for me, and that I wasn’t alone. It wasn’t an instant thing, and the music wasn’t solely responsible. But it wasn’t an accident, either, I don’t think. In December 1991, I’d joined a band for about a month, singing, of all things, 1950s and 1960s rock and soul music. Things got better. Got laid. Met my wife. Got a better job. Got married. Had a daughter. Bought a house. Started writing in earnest. Got creative. These days, I’m happy. There are simple pleasures – a Nirvana song, a superhero movie, a great comic book or novel. No, Nirvana didn’t save my life. I did. But they helped.

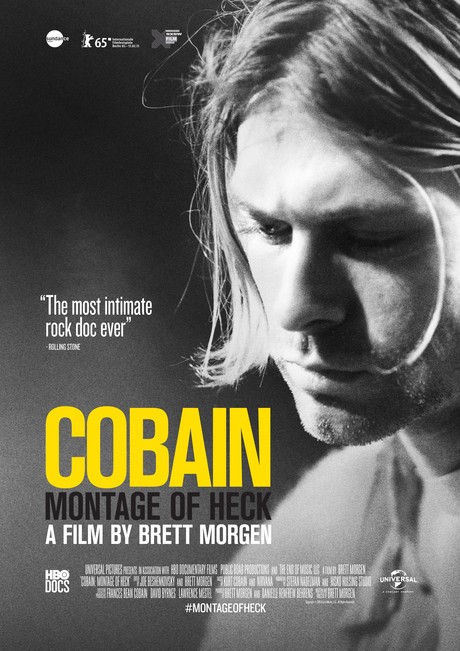

Kurt Cobain got saddled with the “spokesman of a generation” handle, and he always hated it. That’s because he wasn’t a spokesman, not the voice of Gen X, not the symbol for disaffected youth. He was just a man who said what we were all thinking. But he was as flawed and broken as the rest of us. Perhaps that’s why we listened, because he never pretended to be above it all. Brett Morgen’s remarkable documentary, KURT COBAIN: MONTAGE OF HECK, respects Kurt Cobain enough to be honest about the fact that Cobain was a hurting man, deeply depressed and addicted, a weak vessel for all of our hopes and ambitions. Kurt was both hero and asshole. A father who completely loved his wife and daughter, but couldn’t break out of his own self-doubt and his addiction to heroin. Full of contradictions, as we all are, except his contradictions were under a spotlight for all the world to see.

Morgen’s film, created from hundreds of hours of art, music, video, and the most intimate moments of Kurt and Courtney Love’s marriage, is stunning in its power, because outside of all the bombast and the way Kurt’s world exploded beneath him, Morgen wisely remembers that Kurt was a sensitive man who was not equipped with what stardom brought. Even as Kurt wanted to shy away from the limelight, he craved it; he showed his disdain for the rock lifestyle, even when he fell victim to its most addictive trappings; Kurt put the people who cared for him at a distance, but he also wanted to be accepted, embraced, loved. Contradictions.

Morgen animates some audio sequences, and the effect is striking. One sequence, as Kurt describes his first sexual experience, is raw and brutally honest. MONTAGE OF HECK also features interviews with Krist Novoselic, Courtney Love, Kurt’s mother and first girlfriend, and they all describe a person whose public face was at odds with his private one – a man who could not stand to be humiliated, afraid of rejection, but one who was undeniably talented and happiest when he was performing. Kurt recorded sound collages which make up much of the soundtrack, and even those audio assortments are startlingly original, showcasing Kurt’s formidable talent. Morgen marks the passage of time with snippets of Kurt’s writing and art, animating several of his paintings to gorgeous effect (even the album covers). Although the important pieces of Nirvana’s history are there – their signing to Sub-Pop, the recordings of the albums, the Lynn Hirschberg hatchet job in Vanity Fair – they are delegated to the context of Kurt’s life, instead of being front and center. This gives MONTAGE OF HECK an elegance and a flow – we’re exploring a life, not a history lesson.

The best, most heartbreaking scenes are the moments where we see Kurt and Courtney enjoying simple married life. Seeing their love for each other shine in their eyes, and their love for little Frances, and yet… it still wasn’t enough. MONTAGE OF HECK demonstrates just how insidious addiction and depression can be – even in those happy, lovely moments, the specter of what is to come hangs over those sequences. Simpler minds will look at these scenes and wonder how Kurt could do what he did, and dismiss just how debilitating and crippling the diseases of addiction and depression can be. Many fight them every day, with the victories counted in days. Some simply can’t bear the weight. MONTAGE OF HECK never makes excuses for Kurt, never tries to deify or idolize him. But at the same time, Morgen takes great pains to show us that this was a life in turmoil, under a constant barrage. If his closest friends and family couldn’t get to him, what chance do any of us have under that relentless burden?

In December, 1993, I saw Nirvana perform, with the Breeders and Shonen Knife. I had met my wife (though neither of us had realized it yet), and I saw the show with my two best friends at the time. I hadn’t won the fight, because life is always a fight. Your triumphs are in the little things, the simple pleasures of the heart. I suspect that most people my age who see MONTAGE OF HECK will add all their personal baggage of their lives to it, which is understandable. I know I did – Kurt Cobain entered into my life at its most critical juncture, and even though time has given me distance and perspective, seeing this film made all those emotions and memories come rushing back. But Brett Morgen’s film is more than a simple look at a time now gone. MONTAGE OF HECK celebrates a life, and yet reminds us of what was lost – a father, a son, a husband, and an artist. This is one of the best films of the year, and you can see it this month on HBO.

Nordling, out.