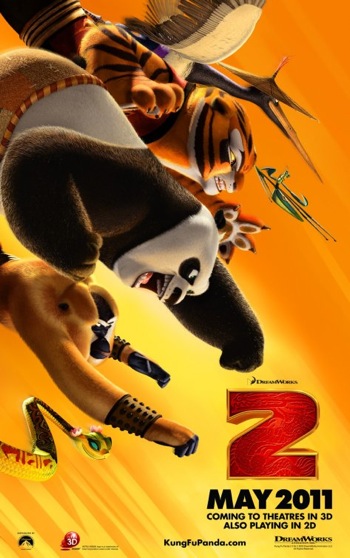

About six years ago, while researching an article on anime, a director in the employ of DreamWorks Animation told me about a forthcoming project called KUNG FU PANDA. Though the film was still a few years from release, he had seen some early footage, and was genuinely excited. This wasn't your typical DreamWorks Animation film, he said; it wasn't crammed with pop culture references and nonstop groin assaults. No, it was basically a child's first Shaw Bros; the simple story of a portly panda's improbable transformation from noodle server to almighty "Dragon Warrior". movie. I loved everything about that idea.

Amazingly, KUNG FU PANDA more than matched that hype. It was a tremendously entertaining martial arts flick that just happened to be animated and pitched to families. Though it was stocked with instantly-identifiable voice actors like Jack Black, Dustin Hoffman and Angelina Jolie, there was no sense of pandering at all. This was a movie made by people who loved the genre, who wanted nothing more than to make an action-comedy that stood shoulder-to-shoulder with the likes of DRUNKEN MASTER (while, content-wise, being appropriate for all ages). It was ninety minutes of pure chopsocky joy.

And they've done it again with KUNG FU PANDA 2, a sequel that recaptures the rambunctious energy of the first film while exploring its protagonist's abandoned past with surprising sensitivity (seriously, this is one of the best family movies in recent memory to deal with the topic of adoption). Unlike most of this summer's offerings thus far, there's nothing lazy or recycled about KUNG FU PANDA 2; at every turn, it knocks itself out trying to top the first. And since there have been some key changes behind the scenes (Jennifer Yuh has taken the directorial reins from Mark Osborne and John Stevenson), one has to give a good deal of credit for the sequel's success to returning screenwriters Jonathan Aibel and Glenn Berger.

A writing duo for the better part of two decades, Aibel and Berger honed their all-ages expertise during their six-year run on Mike Judge's animated TV series, KING OF THE HILL. Though that show had more of an adult bent, they still had to be mindful of the show's broad appeal - which, it seems, broke them of the desire to smuggle ribald material into family entertainment. Now that they have families of their own, they're focused on crafting four-quadrant movies that respect the audience's intelligence, even when the four-quadrant movie in question is an adaptation of the board game CANDY LAND (which they vigorously defend in the below interview).

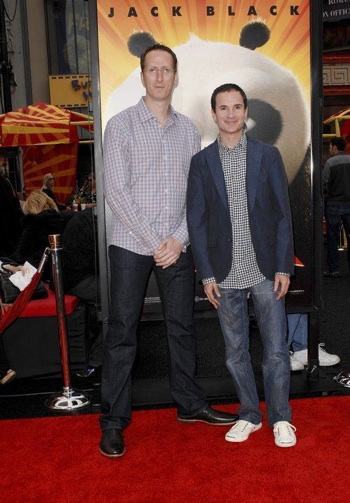

When I chatted with the affable Aibel and Berger last week in Hollywood (Aibel in person, Berger via speakerphone), I figured we'd cover every aspect of how they write as a team (including how they manage the transition from KUNG FU PANDA 2 to, say, ALVIN AND THE CHIMPMUNKS: CHIP-WRECKED). Fortunately, the fellas are very forthcoming about their experiences in the studio system. As with my recent Craig Mazin interview, if you've any interest in one day cracking the professional screenwriter ranks, this is a pretty good read.

One thing I did not expect, however, was to kick off the interview talking about Harry's twelve-year-old rave for their unproduced FREDDY VS. JASON screenplay (which was nearly directed by makeup f/x maestro Rob Bottin). That was a fun little detour.

(l. to r. Glenn Berger, Jonathan Aibel)

Jonathan Aibel: We're thrilled to be here with Ain't It Cool News. You guys were among the first to tell the world that KUNG FU PANDA wasn't going to a stupid kids' kung-fu parody.

Glenn Berger: Jon, I thought you were going to say that Ain't It Cool News gave us our first positive review ever. Fifteen years ago, Harry Knowles was slipped an early draft of FREDDY VS. JASON that we wrote. It was the first screenplay we'd ever written; we'd never even written a spec. We were TV writers. We were on KING OF THE HILL, and they were looking for writers for FREDDY VS. JASON. And the director at the time, Rob Bottin, who ended up not staying with it, was a fan of the show. We somehow got this job, wrote a draft, and someone slipped it to Harry. We had our screenplay reviewed, and Harry... it was so flattering and so cool, that even though we were, like, number eleven out of twentysomething writers, and not a single thing we wrote ended up in the final movie, we still hold onto that as one of our best reviews.

Mr. Beaks: God, I didn't know that!

Berger: It's in your archives. We actually met Harry, and I don't think we had the guts to bring it up to him because it would've seemed like ass-kissing. So now we can just say it to you.

Beaks: That film went through so many permutations, but a Rob Bottin-directed FREDDY VS. JASON is something that I would've liked.

Aibel: We, too. He's incredible. He was really intense, but really fun to work with. He has - or had - a cool house filled with memorabilia from his movies. You walk in, and he's got the dog from THE THING, where everything burst out of it. And he's got ROBOCOP.

Berger: Take that, Guillermo del Toro! They should be roommates. They should just pool their collections and hang out together.

Beaks: I think they're friends.

Aibel: Well, they worked on MIMIC. Rob did some creature design for that.

Beaks: And if they're still friends after MIMIC, then it's a real friendship.

Berger: I didn't know we'd be talking about Rob Bottin today. That's so weird.

Aibel: We're tired of talking about us! Let's talk about Rob!

Beaks: Well, let's start talking about you guys. You really knocked it out of the park with the first film. It was a rarity in that it satisfied adults as much as children. Stepping back in, how do you capture lightning in a bottle twice?

Berger: The first problem is, you knock it out of the park the first time around, then they build a bigger park. They move the outfield fence further back, and they give you a smaller bat. (Laughs) Actually, they give us a bigger bat. The challenge was always to keep what was good about the first movie without just remaking the first movie in a new place with a different villain. I think we were fortunate in that we have a wonderfully imperfect main character. Po is vulnerable in such a deep, emotional way, that, just because his dreams came true at the end of the first movie and he beat Tai Lung, it's not the end of his journey. I think what's really cool for us personally is that he represents people who have the outward trappings of success - in his case it's the Dragon Warrior-ness; for other people it's money or good looks or fame or power - and the realization is "Well, that's not necessarily enough. That's not going to make me 100% happy." And if you're not happy fundamentally with who you are - or in Po's case, if you don't know fundamentally who you are because there's a mystery surrounding your birth and identity - then that's something that needs to be addressed. So we felt like there was a lot of emotional meat on the bone that we could gnaw on for a few more movies. That was the biggest gift we were given: the happy accident of him being adopted in the first movie.

Beaks: So that wasn't intentional? You weren't thinking ahead to the second film with the orphan thing?

Aibel: It was a gift we gave ourselves. We didn't even know. It's like we wrapped it, and then three years later looked under the tree.

Berger: We hid it somewhere where the kids couldn't find it, forgot about it, found it, opened it again, and were surprised that we ever bought it and liked it.

Beaks: In this era of franchise building, whenever you're writing a film that's intended to be stretched out over several chapters, you have to take all of these elements into account. As you were writing KUNG FU PANDA 2, did you have to stop and think, "Okay, we're going to be on the hook for a couple more of these?"

Aibel: I don't think anyone ever thinks that. It's hard enough just to make the movie you're making. I've never heard anyone say, "No, no, don't put that in! Save that for the third or the fourth!"

Berger: As Jeffrey [Katzenberg] would say, "If you've got a good idea, put it in now because who ever knows if you're going to get another chance. The only way you get to make another one is if you make this one as good as you can make it - and that involves using all of your greatest ideas now." On the other hand, Jon and I came from television. We did six seasons of KING OF THE HILL. That's hundreds of episodes. And you just have faith when you're doing episodic television... that well-conceived characters are three-dimensional enough that there's always going to be more to tell as long as you treat them realistically. It's only when you have cartoon versions of a character that you run out of things to do with them.

Aibel: At the very, very end of [KUNG FU PANDA 2], there's a little tag that everyone will see and say, "Oh, that's just so they could set up the third one!" But without giving it away, that isn't the point of it. The point is that the movie ends with Po saying, "I know who I am," and then there's a little thing that says, "Do you really?" That's kind of Po's journey: just when you get to the place where you're sure you've got it all figured out, there's always something else coming that causes you to question everything all over again. That's what that means to us.

Beaks: Since you brought up Jeffrey Katzenberg, how involved is he?

Aibel: He's incredibly hands-on, but incredibly respectful of the process. When we were coming up with the idea, we would send him outlines and pitch him the story; he would give us his take, but he would never say, "It has to be this." He definitely watches every frame of the movie, but never in a way where he's saying, "You must do this." Often he'll say, "Here's an idea!" But it's sort of at your peril to just do that idea. If you present that idea to him and he says, "That's no good," and you say, "But Jeffrey, that was your idea," he'll say, "I don't care if it was my idea! Your job is to give me something better than my ideas!" He's never happy if you just give him what he says he wants; he'll give you ideas, but your goal is to let that be the floor rather than the ceiling. And for us, it's a rare studio where you can sit face-to-face with the head of the studio and say, "We have this idea, we have this concern..." and then get a copy of your script with his notes written on it. Or if you have a question, you can email him or call him and ask him about it. That doesn't happen anywhere else. It's wonderful. It really is a place where the executives are very collaborative with the directors and the animators; every storyboard artist gets a chance to pitch their sequences to Jeffrey, and he loves working with the animators and watching what they do.

Beaks: So does working for someone like Jeffrey spoil you when you go to write for other studios?

Berger: I think he knows that. He's always very gracious. In our seven years there, we've seen many people come and go. We've done outside projects. But every time someone is saying, "I think the grass is greener, and I want to go," he's always gracious and says, "Please go, and do whatever you dream of doing. But always know the door is open, and you're always welcome here."

Aibel: It's very Amish in a way.

Berger: (Laughs) I think he only can do that because he's worked at other places. He knows he's got a special place [at DreamWorks] where you're supported. I think that's the key word. You are given all of the freedom to fail or succeed: he'll give you all the resources to help you succeed, and he'll also give you full responsibility. DreamWorks Animation is just a remarkably free place. I think Jon and I can appreciate it more than others because we are simultaneously working elsewhere. For the people who have only worked at DreamWorks, you may have illusions about what it's like elsewhere, that maybe it's better. But DreamWorks is an amazing place.

Beaks: Did you know which voice actors you were writing for on the first film? If not, did knowing who you were writing for this time out make it easier?

Aibel: On the first film, Jack was cast, and I believe Ian McShane and Dustin were, too. But the Furious Five hadn't been cast. So we were there when Angelina was added. And then you get David Cross. I think Lucy Liu and Jackie Chan had been cast, but then you get Seth Rogen. So you start hearing these other voices, and it's like, "Okay, now that I know Seth Rogen is Mantis, that's great. Give that joke to Mantis." On the second one, we knew who all these people were, so that was great. One of the frustrations with the first movie was that we spent so much time dealing with Po's origin story that we didn't get the screen time with the Furious Five we wanted. And when you have all of these comic actors, you want to give them as many lines as possible. In this case, it was great to have them on the journey with Po, and let them have a little more screen time.

Beaks: How do you guys break up the work?

Berger: We do everything together. We've learned. We've done this long enough to know that two heads are better than one. If we split up stuff at all, it's always at the stage when the very detailed outline has to be turned in, the rough first draft of the script. So instead of both of us staring at the same blank Final Draft screen, we'll say, "You take that half, I'll take that half," and you put it in from descriptive paragraph in the outline to the actual slug line of "INT. JADE PALACE". You get that out, and now we're no longer looking at a blank screen; we're looking at some magical elf over the night gave you a first draft, and you get to rewrite it for the first time. But other than that, everything from breaking the story with index cards and a cork board to the final proofread, we do it together.

Beaks: How do you guys resolve conflict?

Aibel: Usually if one has one idea and the other has a different idea, we'll just argue, debate and discuss and ultimately come up with a third way that makes us both happy and hopefully is better. Or one of us will say, "You know what? I just don't care anymore. Put it in."

Berger: (Laughs) We used to have systems in place; each one of us had a certain number of chips you can use. But we've been doing this so long now that, as Jon said, it's easy to gauge when someone is passionate about something. So the choices are, "He seems really passionate, and I don't care enough to fight," or, more likely, we both care a lot, we're both fighting and it doesn't get resolved until there's a third option - which is something I keep trying to bring to bear on my marriage, and my wife is refusing to accept it. Endless arguing is not the sign of a troubled marriage, but a healthy partnership!

Aibel: I'll talk to her. Also, you could be writing a scene, and you just don't know how to start a scene. "It has to start this way." "No, it has to start this way." So you put them both down, and you come back to it a week or a month later, and you both say, "Oh, it's so obvious." Sometimes you just don't know in the moment, and you're convinced it's the most important thing, but then when you get past it, decisions you make later have affected that and you can approach things more clearly.

Berger: Most likely if we were are arguing that much about a joke or a scene, there is something so fundamentally wrong with that scene that the basis of the debate is moot. We just wasted a whole bunch of time because all we've done is point out that that scene shouldn't exist at all. But that's useful, too. Another virtue of experience is... when we first showed up at DreamWorks, people were like, "You guys argue a lot." To us, that's our exploration. As much as an artist would use pencil before they start using a marker, we verbally discuss and figure out what we have to do by talking about it.

Aibel: The key, of course, is to discuss, discuss, discuss, and then decide and execute. But you have to get to the execute part, or else you're just discussing and nothing gets done. That's something you hear at DreamWorks directed to all the filmmakers: "Decide and do it." Because the sooner you decide and do it, the sooner you can change your mind and redo it. But if you don't pick one and start that, it's just talking and talking. And you don't know: you might end up liking what you've done.

Beaks: Because you're writing for a family audience, do you ever come up with a joke and say, "God, that's great, but we can't possibly put that in a family film?"

Berger: Yeah, but that's been happening to us since our second job in Hollywood, which was a Nickelodeon sketch comedy show. We have a career's worth of jokes that are funny to us, and inappropriate for a family audience. You laugh at them and you move on, or you put them in a special folder, and some day when we write our hard R-rated comedy, we'll get to use them all. The nature of any writer's room is that you're going to end up with a bunch of jokes that make you laugh that you know you can never use. That's just the side-benefit of the job.

Aibel: Having done this long enough, we don't get thrills out of, "Let's try to sneak that in!" Something that will scandalize the parents, but the kids won't get it? That's something you get out of your system pretty early.

Berger: We definitely did that, though. We did it in our twenties before we had kids.

Aibel: Now, you have to be responsible. You think, "I don't want to have to explain that joke to my kid!" On KING OF THE HILL, there would often be slightly more risque stuff, but Greg Daniels would always say, "Make sure you have an explanation in there, so the parent can turn to his child and say, 'This is what it is.'" So when we added... (Laughs)

Berger: The raccoon one?

Aibel: (Laughing) Yeah. Bobby heard bed springs next door. Was it his grandpa or grandma? And when he heard the squeaking, he said, "Dad, the raccoons are out again!" So when kids would ask, "Why was he hearing squeaking?", parents could say, "It's because he though the raccoons were out." And hopefully you don't get to the point where they ask, "But what was it really?"

Beaks: That reminds me. I interviewed Mike Judge a couple of years ago, and he said whenever people in the KING OF THE HILL writers room would get out of control with dirty jokes, Greg Daniels would just top it with something really nasty as if to say, "Can we move on?"

Berger: That's so funny. We were younger writers then, and I guess now we're realizing, when you say that, that that was an effective management technique. We just thought Greg was as funny and as filthy as all of us. I guess once something is taken to the nth level, there's no need to keep going. Huh. Well, good for Greg. He fooled us.

Beaks: Do you have a desire to go off and do something more adult? And, if so, does your management or agency worry that it might hurt your image as family film writers?

Aibel: No one tells us what to do! (Laughs) I don't know. You see something like THE HANGOVER PART II and say, "Wow, to write such edgy stuff would be awesome!" But at the same time, we were at the premiere with our kids, and to be able to sit there in a movie with your family and see your spouse and your kids enjoying it together... that's pretty good. Maybe we need to wait for the kids to hate our movies before we start doing [R-rated comedies].

Berger: Gary Oldman's said that he's doing [KUNG FU PANDA 2] so he can share one of his work experiences with his children. I mean, they're not going to watch SID & NANCY.

Clearly, that's not what's driving our desire to do these movies; there are other things we can watch with our kids that we didn't happen to write. The truth is that these are movies that we love to see and we love to do; if we're going to spend the three or four years that we spend on these things working our butts off trying to make them as good as possible, we want as many people as possible to see the movie. We're not doing this as a small art-house film. We think it's good, we think it's funny, we'd love to share it with as many people as possible, and if that means it has to be in a family genre... well, that's the way to do it. Plus, it's kung fu. Who doesn't love kung fu?

Beaks: Someone described the first film to me as a gateway drug for kids to kung-fu movies.

Berger: Oh, I can't wait to show my kids SHAOLIN SOCCER. Or KUNG FU HUSTLE. That's one of our favorite movies. It's weird. KUNG FU PANDA, in a way, is an homage to those movies. And now our kids will come at it from an opposite direction, which is to say, "You like KUNG FU PANDA? Maybe you'll like [KUNG FU HUSTLE]."

Aibel: My favorite is ONG-BAK.

Berger: And ONG-BAK is perfect, too, because there's not too much blood; it's just amazing physical prowess.

Aibel: I don't know if it comes through, but ONG-BAK was an early inspiration for [KUNG FU PANDA 2], the idea of the innocent going to the village. At one point we were thinking, "Oh, it'd be great if we had these crime lords in this town and a fight club, and Po had to mix it up with them!" That didn't quite come through, but the early Tony Jaa feeling of the naive guy coming into this town, saying, "I'm gonna show this town!", and no one in the town cares.

Beaks: When you see the finished films, do you ever see scenes executed differently than you imagined?

Aibel: I think the entire moviemaking process in any movie is you see something in your head, and it's never going to be that way. Something as simple as, "In my head, I see the Peacock's Palace a certain way." Then you see the design of the Peacock's Palace, and you're like, "Oh, my god, that thing is huge and ornate! If I could imagine it that way, I'd probably be a set designer instead!" But everything is about... we as the writers are bringing a piece to it, but that's just one of the many pieces, and it's [director Jennifer Yuh's] job to pull all the visions together and make it her own, then take her vision and communicate it to everyone. I think we realized a long time ago that the end product isn't just supposed to be the movie we envisioned, but the movie that everyone collectively envisioned.

Berger: And thank god, too. The other virtue of DreamWorks is that it's a collection of some of the best people in their respective fields. I'd say any time something deviates from what I imagined in my head, it's because I wasn't thinking big enough, and they've just done it bigger and better and more beautiful. I hadn't seen the movie in three months before I saw it at the premiere, and the full 3D and the music... I was blown away. That's not self-congratulatory; that's just totally blown away by the work all the other departments did making this movie beautiful and gigantic.

Aibel: I was talking to someone at the premiere who'd been in London on the scoring stage when the orchestra was recording. He said they were talking about a bassoon part, and discussing it and recording it, and it wasn't right, so they recorded it again. He was convinced this was the most important cue in the movie. Then he watched the movie, and he could vaguely in the background hear this bassoon part. And that's what this movie is: it's everyone being convinced that what they're doing is the most important thing in the movie. And it is as you're doing it. But then someone has to come in and put everything in perspective and say, "The dialogue there is important, but not as important as the visual." Everyone works so incredibly hard on it, that you do kind of lose perspective on what it is we're trying to do here. That's why the director and the producer really have to manage these hundreds of people and corral them. It's a huge undertaking.

Beaks: I'll be blunt with this one: how do you do CANDY LAND as a film?

Berger: The same way we did KUNG FU PANDA. Which is to say that, on the face of it, if ten years ago someone said "KUNG FU PANDA", you could easily get to, "Oh, it'll be a schlocky parody of the kung-fu genre starring a plush toy. It'll be talking down to kids. It'll be filled with fart jokes and people getting kicked in the nuts a lot." Luckily, it was shepherded by a whole bunch of people who were committed to honoring the genre, taking the characters and their situations seriously, making it look beautiful, not having any reference jokes, creating its own world, having its own internal logic and not referring to anything outside of its world.

That's precisely, I think, why we got the job on CANDY LAND. But that's also why we were excited about getting the job on CANDY LAND. It's something that, on the face of it, seems like a huge challenge: it's a board game for kids, and there's no strategy involved. But what it does have is the opportunity to set an action movie in a world made of candy. So when we meet with the director, Kevin Lima, and he says, "I want this to be LORD OF THE RINGS but with candy," you could either laugh at that, or say, "If you could pull that off, that would be really cool. We'd love to be a part of that because we love LORD OF THE RINGS and we love candy."

Another thing that's really important to us is amazing action sequences with character-based comedy, and characters having an emotional story that rings true - and we don't care if that takes place in mythical China where animals do kung fu, or in a world of M&Ms, or in our world. Frankly, we'd rather do it in CANDY LAND, because, fundamentally, we're going to bring to bear the same skill set we'd bring to any movie, and the same emotional story. There's something very unique about if you can do that same thing, but set in world of candy, that's going to be unlike most movies.

Aibel: Every movie is about the execution. I don't think there's a great movie where if you said the logline to it, someone wouldn't say, "That sounds terrible!" If someone said, "There's this archaeologist, and he tries to steal this relic from the Nazis," you be like, "I don't know, that sounds kind of lame." Anything is going to be in how it's done. And hopefully this will be done well. We're certainly approaching it in the spirit of sincerity. We want to tell a great story, and it just happens to be based on CANDY LAND. Kevin and everyone at Hasbro aren't just like, "Let's just take this board game, and make a movie to sell more board games." It isn't that at all.

Beaks: And you're doing the next ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS?

Berger: We already did it. We wrote that probably a year ago now, and they're just doing the post on that.

Beaks: Is it a different skill set you're bringing to those films?

Berger: The biggest difference with the ALVIN movies is... in KUNG FU PANDA and CANDY LAND, we're involved in creating the whole world - with a whole lot of people, of course, but there are world-creation aspects. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS, aside from the fact that it's a fifty-year-old property that the Bagdasarians get to shepherd, already existed both in the popular culture and in the modern movie version of it. So we were coming into something that already existed, and trying to be true to that vision, but certainly having to color within those lines.

Aibel: But I would say that when we're approached with ALVIN 3, the thing that makes us decide whether we want to do it is, even if it's singing animals or kung fu pandas or candy people, you have to figure out some way to put yourself in the story and find something meaningful. I know that sounds crazy with singing animals, but for us it's a father-son story, and we're fathers. In this case, it's called CHIP-WRECKED; it's about what happens if a father and his sons are separated. That's something you can relate to, and that's how you find your way into a project. In that case, all projects are similar; you're saying, "What can I say in the story that's meaningful to me." Process-wise, it's a little different because our involvement in the CHIPMUNKS movies is "Here's the script, get notes, here's the rewrite..." and they go off and make it. In a fully-animated movie, the making of the movie is the discovery of the movie. So the process of making it is, in a sense, the writing of it, too. So we're involved in that as it's being made over the two-and-a-half years, versus the standard, "Here's the script. Go film it." That's more the model ALVIN follows.

Beaks: Do you guys have directing aspirations?

Aibel: Maybe if the right project came along. We keep saying, "Let's wait for someone to ruin one of our movies before we decide to take it on our own." We really love what we're doing, and enjoying it, but we may get to the point where we say, "You know what? This is a small, personal story that we'd like to tell on our own." I think certainly Judd [Apatow] has paved the way for people to realize, "I can tell stories that speak to my experience and what I'm going through, and now direct them." That's definitely a model we look to in the future. Directing a movie takes a lot of time. Not that writing doesn't, but we have the luxury to do a number of projects simultaneously. With KUNG FU PANDA, it's many years, but it becomes part-time and lets us do other movies, too. It's nice to be able to drop your head into different worlds instead of being in one for a year or two or three.

Berger: I also think that, temperamentally, I'd rather be in the position of imaging an amazing world than have to then be the person tasked with designing and executing and building that world, and then being asked, "Is that world the exact color you had in your head?" I just trust that there are so many people who are good at that, I'd rather just say, "Here's what I came up with. Now go do it!" As Jon pointed out, so far we've been astounded and impressed with what people have come up with, so why would we want to mess with that?

Here's hoping they don't mess with the KUNG FU PANDA formula, because it's working beautifully at the moment. I see no reason why they can't keep this series running for another few films.

KUNG FU PANDA 2 is currently in theaters, and is well worth your time and money. Check it out.

Faithfully submitted,