It’s not an uncommon notion that Marlon Brando was the finest screen actor that ever lived. The roles he took were a huge part of that: STREETCAR, THE WILD ONE, ON THE WATERFRONT, THE GODFATHER, LAST TANGO IN PARIS, APOCALYPSE NOW. But there was something more to Brando than mere talent, something magnetic and mysterious in a way that very few movie stars could ever dream of emulating. His purchase of the French Polynesian location of MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY, his controversial acceptance (by proxy) of the 1972 Best Actor Oscar, and his increasingly erratic on-set behavior remain the stuff of legend, as does his penchant for improv and deep, intensive characterization. He lived a rather isolated life before he passed in 2004, leaving behind mysteries regarding his many love affairs, the relationships with his family (including his late children Cheyenne and Christian), and his conflicted feelings for the profession that made him wealthy and internationally respected.

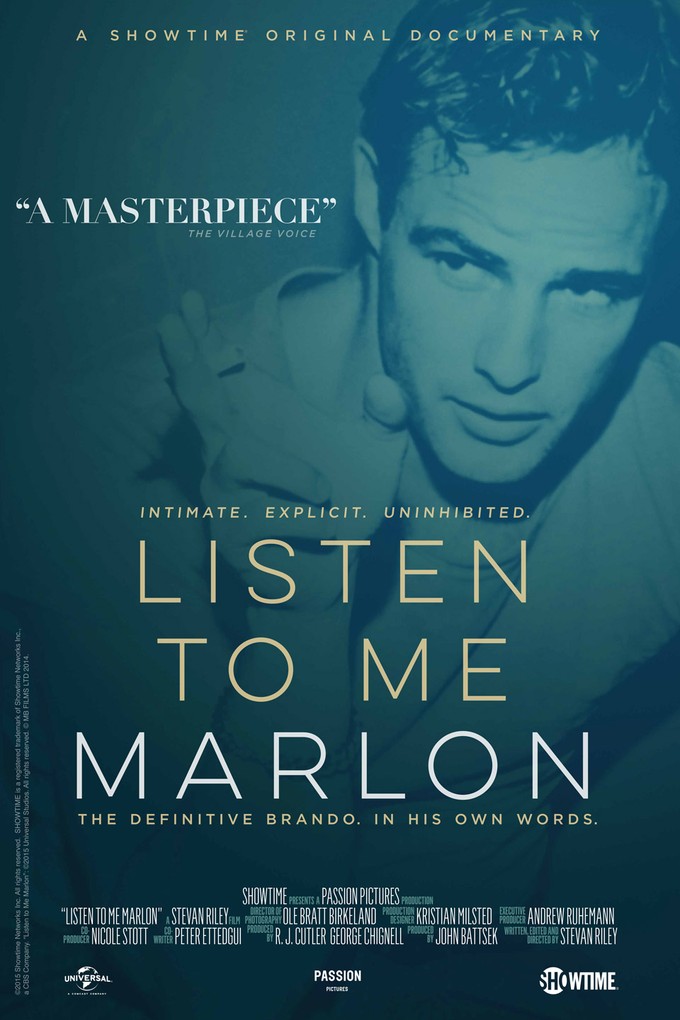

As it turns out, Brando recorded extensive audio of his thoughts and musings, which director Stevan Riley has whittled down into the Showtime-produced doc, LISTEN TO ME MARLON. By solely using Brando’s own personal accounts of the various events of his life accompanied by stills, movie footage, and home movies, Riley simultaneously avoids the pitfalls of by-the-numbers, “talking heads”-style documentaries about Hollywood, while also providing a closer, more intimate look at the two-time Oscar-winner than most have ever been afforded. Choosing his clips carefully, he creates a narrative that takes us from Brando’s beginnings as a young stage actor from Nebraska to the larger-than-life icon that struggled with his media image, his weight, and the balance between his personal life and his status as Hollywood royalty. It’s surprising to hear the notoriously reclusive Brando speak with such eloquence about the most personal (and juicy) facets of his life, and it’s a testament to Riley’s work with the late actor’s estate that the film feels very much like a “behind-the-curtain” look at someone many of us have wondered about or, at the very least, revered.

Riley, an Oxford-educated documentarian also responsible for the sports doc FIRE IN BABYLON and the James Bond-centric EVERYTHING OR NOTHING: THE UNTOLD STORY OF 007, spoke with a quietly lovely English accent about Brando, his looming legacy, and the process of condensing the man and his legend into a 100-minute film:

VINYARD: You’ve done a few documentaries, but this is the first one with a subject as loaded as Brando.

STEVAN: It’s a bit more adult than the other ones I’ve done, in a strange way. I did a couple of sports docs. Last one was on James Bond.

VINYARD: Sure, EVERYTHING OR NOTHING.

STEVAN: But this was a chance to do something quite different, and slow the pace up, and try a different space, no talking heads. Deal with some more adult themes. Bond felt a bit flippant at times, even though it was dealing with personal, behind-the-scenes stuff. This was like a very layered, introspective journey, which I thought would be really nice for me to tackle. It felt like a nice departure.

VINYARD: What led you to the story of Brando?

STEVAN: The films I’ve done with Passion (Pictures), they’ll call me up and say that the access is there. “Are you interested in doing a film on Bond?” And I kind of go off and find my own way in. It’s never really predicated on my own interest in it. As it happens, I love Brando’s roles, but I knew nothing about his life. I do character pieces on the whole, so I thought that his would be an interesting one because he’s so complex. To try and crack at untangling this knotty riddle around his life was very interesting for me. That’s how I first got involved.

VINYARD: So they approached you?

STEVAN: It was with the access. 10 years after Marlon’s death, the estate was getting their whole act together. They were archiving and labeling all of Marlon’s personal effects that had been in storage for 10 years. Boxes and boxes and boxes, just sitting in Hollywood vaults, hadn’t been touched, hadn’t been labeled. At the same time, the idea for a documentary came up. They were talking about doing something to just sort of keep his legacy alive.

One of the guys in the archive, called Austin (Wilkin), had helped in the production on another film for Passion, so he knew John Battsek. He got in touch with John, said, “Would you like to do this?” John phoned me up and said, “Would you be interested in doing this? Would this be up your street? Would you want to develop the story and direct it?” I went off and wrote the treatment, which was based on lots of things.

I normally just get all the books. The first thing that I do, I get every single book I can. Read a lot of books for three weeks and researched everything I could. I had a handful of tapes- all the archive boxes were coming out, and there were these tapes that were quite exciting. I was given about six or seven initially to listen to, and I was very fortunate that some of these tapes were very revealing, and would end up being some of the more important tapes in the film. One tape had a couple of private conversations with his friends where he was very open.

Then, I just had this fanciful idea initially, “Could you imagine if you could tell it in Marlon’s own words, how interesting that would be?” But it was really not a possibility. I structured the proposal around it, the pitch, but I never knew it would be possible. You knew there were more tapes, but what was on them? It could’ve just been recordings of anything, it could’ve been dead or empty tapes. We got approval from the estate on the back of that pitch, it was called, LISTEN TO ME MARLON, and then the thinking becomes, “Okay, now we have funding, shit, we’ll try and do this now.”

I was a bit worried that it wasn’t even a possibility, so just in case, I went out and did research. I was quietly looking for people in case I needed interviews. But the more books I read, and the further I got in, you were still left with some different version of Marlon, as we all have different friends who all have a different perspective on you. There was no one who was with him that entire time to tell his full life story. There was a potpourri of heads giving half-baked impressions of him. So I started getting more and more encouraged and attached to the first idea. To clear up all those myths, and to do it in his own voice would be a lot cleaner, narratively speaking, and would just clear up the riddle better than anyone else could, including myself.

Then, the push was to get everything out of boxes, record the tapes. Down to the last minute, more tapes were coming through, more tapes were getting transcribed. They got through the lot of them in about a year. I was in the edit for about 9 months, and stuff was still coming, imagine that. When I got 5, 10, 15 minutes into the edit, it was all taking shape. Initially, it was all a black screen, but I just put the music and the audio together, so I was comfortable with the narrative thread. I had ideas for the visuals, but I wanted to sort that out later.

VINYARD: Was it the estate who were the ones rifling through the unlabeled tapes and letting you know how they fit into your treatment?

STEVAN: No, they would just digitize them and send them over with a rough idea of what might be on them. But everything came over. They had their work cut out trying to do all the documentation and the photos. I was kind of pressuring them to label it so I could use it in the edit, put numbers on it and things so I could actually conform the film at the end. So they were helpful in shifting their whole archive process to serve the edit, in the end.

I had really good relations with them, and if something popped up, I might phone up and just tap their shoulders and say, “Could you look into this? Are their any documents around?” and stuff like that. They were always a willing resource, and understood that the film would go into these more difficult areas, including his addiction and the shooting. All that stuff was within limits because we were talking about it, and I was quite encouraged that they’d indulge those conversations with me and they wouldn’t close it off and helped me find stuff I needed.

VINYARD: Who were you specifically speaking to?

STEVAN: Two people there. One lady called Avra Douglas and Austin Wilkin. They were in there pretty much full time. Once we locked the tapes, as soon as the tapes would come in, we’d send them to get transcribed. There were folders upon folders. I would sift through each folder with a cup of coffee, and just go through with a highlighter and break down all the transcripts into tiny story elements that I’d label in the margin, which confirmed to the shooting script.

So I had to know what my labels were, because I had a rough idea of how I wanted to approach it, in terms of it being his postmortem, and having the layers of the boy and the old man. Starting with the killing. That was all in the proposal. Then I would do these little margin notes, and then I had 400 headings across two sheets. It was all movable stuff.

VINYARD: Was there anything in the transcriptions that made you want to add something to the script that wasn’t there before?

STEVAN: There’s always nice surprises and things that would pop up. I wasn’t aware of some anecdotal stuff, like that he was interested in theology, that was really interesting. I could see his worldview, about how we lose track of the truth, how we just lose our grip of the truth really quickly when myths start coming into play. The myth of evil people, which he was obsessed with, informed his choice of roles, THE GODFATHER, YOUNG LIONS. He’d revel in playing evil characters in educating the audience on the nature of evil, the hypocrisy of ourselves, that we’re all good people capable of extreme violence within very short notice.

VINYARD: You think that’s part of what appealed to postwar audiences and made him the biggest movie star of his generation?

STEVAN: My mum’s from former Yugoslavia, she’s from Montenegro. She had a poster of Brando on her wall as a kid, and she knew I was doing the piece. I said, “What’d you like about him when you were growing up?” And she said, “He just seemed like a nice, honest person, and humane.” All these sort of things that I was finding out in the course of the research were sort of instinctive to a foreigner. She couldn’t speak English at the time, but she just felt this presence on the screen.

He was the first tortured leading man. He brought faults into the leading character. It was always faults that we could see in ourselves, that made him more sympathetic. Even the documentary reinforces that, because we see that he delves into his own insecurities and goes to places that a lot of us…probably do ourselves, but not in as structured of a way as he resolved these issues that he found troubling.

VINYARD: Do you think that when the cultural tide shifted in the ’60s and then later in the ’80s, do you think that contributed to his career slumps as well?

STEVAN: Maybe. He created problems, he ran into problems with Hollywood. He had about 13 box-office flops in a row, which wasn’t that great. So he wasn’t that gold midas touch anymore. By the time of THE GODFATHER, he needed a success, and I think he realized that, because he was running short on money. He had lots of debts, lots of legal cases with his exes, he was looking after all these kids and dependents, properties, and Tahiti, everything he had paid for. He got $50,000 for THE GODFATHER, then he sold his gross points for next to nothing.

There were a few reasons. There was the myth that he was uncontrollable. I think he could be…he could definitely be difficult. He’d take on directors and producers. I think there was also something about the diligent work horse about him. Under the right supervision with the right script, you could see all his ideas coming back. I mean, he wanted to do well. I think it upset him when he performed below par. He was quite a perfectionist when he was committed.

VINYARD: I heard one story, I believe it was about THE ISLAND OF DR. MOREAU, where someone said that Brando would meet a director, and within five minutes of meeting them and hearing their vision, he’d decide whether he was actually going to work with them, or if they were nothing and unworthy of his energy.

STEVAN: Yeah, I think so. There were only a few times where he felt like he was really nurtured. He needed that, because he realized that it was a terrifying leap to take, as an actor. You want someone to hold your hand, you want a good director there who’s going to encourage you to do the right things and push you in different directions. Have a team, who doesn’t want that? I think he had good experiences with Kazan, obviously, although he criticized Kazan in other breaths. Always that conflict, even with the people he loved.

He liked Coppola, but you hear him ranting against Coppola in the film. For good reason there, though. I agree with him. I think there’s a bit of hypocrisy in HEARTS OF DARKNESS, when Coppola says, you know, “It was a mess, and I didn’t have a script, and what are we gonna do?!”, and then he criticizes Brando for running over by two weeks! The option was either hold the production and go and rewrite the script for a few months, or improvise with Brando. Anyway, he did improvise with Brando, and then ruptures him for it. Brando wasn’t that overweight. It wasn’t obscene.

VINYARD: I was surprised. You see the behind-the-scenes footage of him on-set, and I went, “Why did he have to frame him like that in the film?” I always thought he was gargantuan, and that’s why all the framing was up-close.

STEVAN: It even served the creativity, because Brando was the one, and this has been confirmed by Vittorio (Storaro), who dictated the lighting there. So even if he’s wearing a black top and he’s coming in out of the light, it’s all about his face. It worked out great, it was a happy accident. He shaved his own head. I spoke to his personal assistant, who said he had read Heart of Darkness, and had all the papers on his bed. She was quite surprised when she read about that later, ‘cause she’d gone to clear his bed up and saw his books on there.

I read all the correspondence between Coppola and Brando in the aftermath. Brando was threatening to sue Coppola, because he owed him a million for (APOCALYPSE NOW). Partly because he only got $50,000 for THE GODFATHER, didn’t get hired for GODFATHER: PART II because he didn’t have enough money, he just wanted his money come the third crack of the whip. When Coppola was saying, “I don’t got it,” that was another beef going on in the background. Coppola did that interview with Life Magazine, which is pretty scathing, and then Brando wrote him a letter, peeved, and then Coppola wrote back and apologized, saying it was all taken out of context.

Anyway, long story, but as much as I wanted to, I felt a bit awkward putting that quote in, ‘cause I love Coppola, and it’s a shame to put any bad vibes out, but I think Brando had the right to actually…he might’ve been a dick on other films, I mean he definitely was, but in that instance, he actually did make that film. It didn’t have an ending, and that was all Brando’s musing. I know, ‘cause I heard the tapes. As I was listening to them, it was quite hypnotic, him just riffing as Kurtz. All those things, he was already interested in.

He took the character of Kurtz from the script of APOCALYPSE NOW- which, when you read it, he was a reprobate character, and he was very ostentatious, and had concubines, and all this sort of stuff- but Brando stripped that right down, and said, “This guys the embodiment of pure evil, and logical at that. How can you rationalize genocide? These are things which he did, and that he set out to do.” And that was it. You see it in HEARTS OF DARKNESS, he just waited ‘till Brando ran out of lines, and he’d go, “Again, again!”

Anyway, I thought Coppola couldn’t have his cake and eat it, in that instance.

VINYARD: And those two films turned out so well.

STEVAN: I think he had a lot of respect for Coppola. There was only a handful of directors- I’d probably say Bertolucci, Gillo Pontecorvo when he did BURN, Coppola, and Kazan, I think those were the ones he really…maybe a little bit with Arthur Penn. They just got on, but I don’t really think he was as inspired as much as with those four. I think those were kind of the top experiences of his life, and he treasured that. For Bertolucci, he went out of his comfort zone. Bertolucci was constantly coaxing him, saying, “We can achieve reality in cinema!” Which was always his ambition since Stella (Adler), when they used to do “truths”. It was almost a rekindling of his idealism with Bertolucci, but he was shocked at the result, I think. When it all trimmed down to an edit, it condensed all of Brando’s insecurities. I think he might’ve balked at that.

VINYARD: Did you consider putting those tapes of him riffing as Kurtz in the film?

STEVAN: There are some bits. You hear some of his prep notes, and before you see Kurtz for the first time, he goes, “So they lie, presidents, congressmen, all of them. They lie when they’re asleep, they lie when they’re alone.” That’s all from Kurtz. And that’s his preparation, it’s not in the film. That’s the kind of stuff he was going for it. Again, he was obsessed with the notion of lies, and myth, and the life we’re living. Even his film ONE-EYED JACKS, the title “one-eyed jack” means “a liar”. You only see one side of their face on a card. Truth, and lies, and honesty, and trust, were just really dominant.

VINYARD: It’s a similarity he shares with Orson Welles, I think. They both were very upfront about how they thought what they were doing was a lie, and that they were charlatans, but they also…you hear Marlon saying, he has an immense respect for the power of film and what the human face can do when shot correctly and performed correctly. That contradiction is powerful, and I think necessary to create a talent like Brando’s.

STEVAN: I think it depended what mode he was in. He knew the tricks of his craft, which were things that Stella taught him, even the idea that you lie in interactions. Like if you feel like shit, the first lie of the day is, “Oh, I feel good, thanks,” when you actually feel awful. Then the cock crows, and you just keep lying ‘till sunset. He said, “You’re lucky if you survive until sunset without a lie, otherwise you’d be dead.” You can employ all of that trickery to acting. That was fine when he was doing a film with a message, then it was all with a good purpose.

But when some film went aground…like MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY for example. In act three, he wanted to recreate what it would be if you started from scratch, and had the chance to build a model society on Pitcairn Island. That was what he got excited about, but act three when in a different direction than what he wanted. A lot of the conflict was there. It was all based on an ideal, you know?

VINYARD: I thought he was a lot more in change of MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY than it sounds like he actually was.

STEVAN: It’s fascinating. I’ve spoken to people who appreciate that film. When he plays the fop, the English fop…it’s such a clever idea to start with someone who’s so flippant and nonchalant and cotton-wrapped, who then has the weight of the world on his shoulders. That was Brando being Brando again, just finding his own character arc.

He was so considerate about it in all his studies and craft. It’s not in the film, but he said, “Your brain is your enemy. Your brain, your thoughts will kill you when acting, not having that spontaneity , that emotion.” If you could cultivate this first, and once you were really immersed in the emotion on your own, and bring those to the forefront, then he says, “Good, you’ve got that, now let’s bring your brain back. Now you have to develop your rational self.” And you fill your brain with as much information as possible, more information than you need, so that it’s so crammed and well-packed that when the moment comes, you can get at it because it will all be there for you, neatly arranged, if you need that info.

He wasn’t actually a seat-of-his-pants actor, he was really studied in his craft, and observed, and was meticulous, almost to the point of annoyance, especially to the women around him, because he’d probe and find you and figure out your weaknesses.

VINYARD: You see footage and you hear a lot about him being a prankster, and him playing a lot of pranks on set, in part to achieve some of that spontaneity, I’m sure. Do you think that the industry didn’t have room for someone like that?

STEVAN: I think it all comes down to control, doesn’t it? Production always wants control over their people under contract and their actors, and they don’t want you to speak your mind. Things would become difficult, and things would become complicated. I suppose Brando was adamant about what he wanted. I think he did use his star power as much as he could. I think he fancied his own intelligence.

He was a very good writer. He had a knack with words and with dialogue, even his improvisations. If you look at THE GODFATHER script and you look at Vito Corleone’s lines against what Marlon said, all the time he’s just manipulating and molding lines to make them sound more natural and more appropriate to the character that he wanted.

When it was used for good, him having control of the script, the ability to rewrite, improvise- obviously not Shakespeare or Tennessee Williams, but if he’s doing other stuff- it’d be good, but if he ran into opposition and didn’t agree with the director’s view, there’s loads of examples where he just felt disillusioned. When he did the film CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS (THE DISCOVERY), and he went in there with so many high ambitions, but he thought it was ridiculous in the end. He thought this is an opportunity to just go completely…

VINYARD: He plays Torquemada, right?

STEVAN: Yeah. I know he was desperately disappointed with that. He thought, “Oh my god, fuck this.”

VINYARD: I love when he says that he’d wear the little hearing aid in his ear, and they’d feed him “the template of the line,” and he’d make the line up basically on the fly, because he could.

STEVAN: The lady at the archive would often do that for him, she was the one on the speaker. He would get a bit frustrated if she didn’t find the right moment, but she was in a Winnebago just trying to figure out what the hell was going on.

VINYARD: Just trying to keep up.

STEVAN: Yeah.

VINYARD: Was there anything you found that you chose not to put in?

STEVAN: There was one scene, actually, that included a love of his, a lady that he had a close relationship with. They had a very tempestuous affair. He pushed her away, she ended up leaving him. I think they were very close friends, and she did stand up to him, which he needed, and I think he missed her terribly when she was gone. She was a white lady, not really his regular type in the sense that she was from near where he was born in Nebraska. I don’t know, maybe he was following into his mother’s figure, but she was a lot different than his mum, and functional and solid for him.

But they got back together. He saw her at a party, and he said it felt like he’d been hit in the heart by a mortar shell. He went up and spoke to her, and then within a few weeks of them getting back together, she died at a car crash. There’s a picture of her at the front of the film, but I edited a scene- it was around LAST TANGO, ‘cause it was contemporaneous with that- I took that out, because it just disrupted the balance of the film. The tragedy, it was just too much, made it a bit too heavy.

He talks about having trust issues. You see him on LAST TANGO when he says, “You’ve always wanted love, but you’ve been distrustful of people.” That really was the story of this other woman. I felt satisfied that it’s there, you still got the anatomy of his character without that anecdote

VINYARD: Would you make that scene available?

STEVAN: I don’t think it’s gonna be on the DVD, unfortunately. There’s no extra scenes. They did not request that. That was Showtime’s lookout.

LISTEN TO ME MARLON is now playing at the Landmark in New York and will pla the Landmark in L.A. beginning on Friday. It will air on Showtime later this year.