Ahoy, squirts! Quint here. There's not a whole lot of movies that I evolve on. I pretty much know from first viewing the general ballpark my opinion on a movie will fall (and stay) in. We all have a few that we either way over-loved or drastically under-appreciated at first glance, that's just how art works, but it's pretty rare for me to revisit a film and completely re-evaluate it.

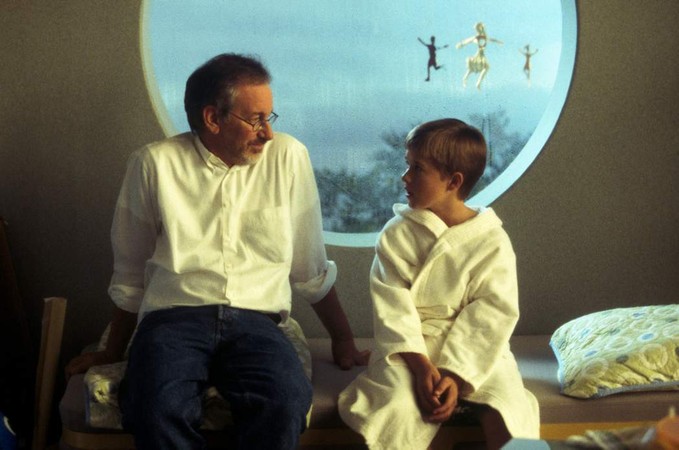

I did just that with Steven Spielberg's A.I.: Artificial Intelligence last weekend and I'm going to try to explain how that viewing altered my take on that film. Re-examining this fascinating entry in Spielberg's filmography isn't a new idea. I'm probably the fiftieth movie writer to do this and there'll be another fifty after me. I can't promise to be the smartest guy to try to peel back some layers on this film, but what I can uniquely do is filter this piece through the prism of my own personal experience, both in direct relation to the movie itself and in more broad human emotion terms.

It was around midnight when I decided to throw on some movie in the background while I multitasked packing for a pending international trip and tidying up my living room for a movie day with my 8 year old nephew. I scanned through the rarely visited movie section of HBOGo (I mean, most people use the streaming service for their original programming, no?) looking for something light and happy. Maybe a musical. Good background noise that'd make me smile when I'd glance up from folding socks.

Oddly enough the title that drew my eye first was A.I. Even though I scanned through their entire film list I kept coming back to A.I. It wasn't at all what I was looking for, but it had been about 5 years since I gave it a run so I figured what the hell?

Instead of having something interesting on in the background while I went about my business I was instantly and immediately hooked. Some two hours later I was crying as the credits rolled. No, crying's not the right word. Weeping. I couldn't stop the tears.

It's been many, many years since I emotionally engaged with a movie so thoroughly that I cried like that. Sure, I've gotten misty-eyed quite a bit. There's no denying I'm a softie, but I can't remember the last time a movie devastated me emotionally. And the kicker is I knew what was coming! It's not like I hadn't watched this movie before. I knew how it ended! But this viewing at this specific time in my life took me from appreciating the movie to flat out falling in love with it.

On the surface this leap wasn't a giant one. I've been defending the movie for years and have always been fascinated by the near perfect combination of Spielberg and Kubrick the final product turned out to be. You can feel Kubrick's clinical touch and sprinkles of weirdness throughout even though Spielberg's trademark anti-cynicism is the primary flavor.

Still, I was one of the many who thought it would have been a ballsier move to end the film with David trapped on the ocean floor, pleading with the Blue Fairy to turn him into a real boy. That felt like a Kubrick ending. That was the ending that told us no matter how much we want something, no matter how hard we struggle on the journey to achieve our greatest desires, sometimes things just don't work out. Sometimes reality gets in the way of our big dreams. So much better than crazy future robots giving our little Mecha hero everything he always wanted because yay, happy endings! Right?

I didn't expect that opinion to change on this viewing, but it did and it's the key to my evolved reaction to the film.

But let's start at the beginning.

One of the first major differences happens right at the top, after William Hurt's great opening scene. By the way, the effect of the Mecha secretary's head opening up is as impressive today as the last time I watched it, but that's not what drew my attention. I still appreciated Spielberg's brilliant visual storytelling (David's introduction is particularly effective), but it was with the characters of Monica and Henry Swinton that signaled the change of empathy that would so drastically alter my emotional connection to this film.

On first (and second and third) viewing I pretty much hated every single human character. Henry never seems invested in David as a son. He's more happy to be chosen by his company to test this new bit of tech. But even worse is Monica, who loves David just long enough to make his abandonment punch a hole in your heart. I saw in her all the people who wanted a cat or dog until they got too complicated and then just dumped them in the woods. I disliked her even more than her petty, borderline sociopathic asshole real son, Martin.

But this time I didn't.

And that realization happened early, when we see her reading to Martin, who begins the story in a coma. I felt her pain, her desperateness not to let go, to not lose hope, and I think that shift in empathy is entirely due to my own personal life experience in the years between the last viewing and this one.

I've always liked kids, which should be a no-brainer since I'm essentially a big kid at heart, but I was never very serious about having some of my own. I think I was a little too selfish, if I'm going to be really honest about it. I liked the freedom I had and the responsibilities of being a parent kind of frightened me.

However, in the last year I've really bonded with a little tyke named Rocco, who is the 8 year old son of some close friends. I was there when he was born and saw him a couple times a year when I'd come over to his parent's house to visit, but it was last year that I really started getting to know him. I'd bring over movies like Monster Squad and Neverending Story and that eventually turned into Rocco becoming my movie buddy.

I've taken him to see a bunch of old and new movies (the last run was a triple feature of ET, Abbott & Costello Meet Frankenstein and Ghostbusters, the latter two in 35mm) and was surprised to find myself looking forward to these movie days more than just about anything else in my life.

This quality time has awoken a paternal instinct in me I wasn't sure I had. Even though this kid isn't directly related to me I love him like he was my blood nephew. It might have taken me 34 years, but I guess this marks me finally growing up a little bit.

And I think that's why suddenly I didn't hate Monica. I could empathize with that basic need of caring for a child. I understood it beyond an intellectual level now. I'm starting to live my buddy Drew McWeeny's fantastic Film Nerd 2.0 column in real life and the tangible bond that it's producing between me and this kid has widened my empathy greatly and opened the door for A.I. to really hit me dead center.

Everything changes when you sympathize with Monica because then David's journey to return to her becomes something you are invested in, not just a plot point. She did a shitty thing, but you just know that if David got back to his mom things would work out. It has to work out! She needs him, he needs her and maybe they can just pop that little monster back into the coma machine and let them have a chance at a real life together.

I imagine this is why a lot of people (if not most of them) get more sensitive to movies after becoming a parent. You can't help but put yourself (and your loved ones) in the scene you're watching. I never emotionally connected at this point in the movie before, but when David's pleading not to be left behind and Monica's anguished refusal to reconsider her decision played out my first tears fell.

A lot of credit has to go to Haley Joel Osment really selling David's desperation and Frances O'Connor's ability to shift between determination, doubt, fear, sorrow and back to desperation again with just a few different facial expressions, but the more I think about it the more I'm convinced it's my own personal experience I brought with me this time that tipped me over.

And if I feel this way I can't imagine how hard this scene hits real parents. I'd take a bullet for Rocco, but even then I realize that's not close to the connection I saw when his dad held him for the first time.

The second act of the movie also fit in with my current slightly more adult life (just slightly more adult life, admittedly. I still have a Sixth Scale Han Solo due to be shipped to me any day now, after all) as David finds a new friend who looks after him, this time in the form of Jude Law's Gigolo Joe. If my emotional connection to Act 1 was the projection of my desire to have a kid of my own filtered through the super fun experiences I've been having with my nephew, Act 2 is actually a closer approximation to the real relationship between us.

No, I don't mean that I'm an utterly charming, thin, dancing love robot... not yet, at least. Gigolo Joe went through his day to day with a grin on his face doing what he's best at until he finds himself thrown together with a kid. Joe's chosen by David to be his friend and guide through the world. In my personal case I'm not preparing Rocco for a the hardships of real life (or protecting him from Brendan Gleeson riding a Moon), but I am guiding him through what I know in the form of movies. It might be a stretch, but that's how I relate to the movie, damn it!

Next to the very end, this was the section of the movie that threw me for the biggest loop on first viewing. The family stuff might have elicited a different reaction from 2001 me, but it did invest me in the movie. Then Spielberg changes gears in about the most abrupt way he can. He uses an emotional blow to transition out of a fairly normal and relatable upper middle class setting to showing us humanity's last gasp in a world that's falling apart.

As a quick aside, the setting of the movie is more timely now than when it was released. It's essentially a global warming scare flick that doesn't beat around the bush about our chances should we let things get too far. The crazy whacked out sci-fi opening narration describing melting ice caps and flooded cities doesn't sound too far off the mark these days.

Anyway, Act 2 shows us this harsh world where humans are looking for a scapegoat for all their problems. Their salvation was supposed to be in the creation of the Mecha, but instead of embracing the machines they fear them.

The warm, inviting photography of the Swinton's home is replaced by a darker, harsher look as David sees what life's like for rogue Mechas and I don't think that's a choice just to propel the audience into a more hazardous territory as the futuristic fairy tale journey really kicks off. I read it as the reality around the Swintons' home being an illusion, an insulated bubble blissfully shielding them from the reality of humanity's pending demise.

In that regard, the most human thing about David is that he's chasing something that isn't real. Ironically his quest to become a real boy is the thing that makes him more than just 1s and 0s clicking away.

My memory of the Flesh Fair sequence in no way prepared me for how brutal it plays out. I think it's because the Chris Rock cameo is so weirdly out of place, but I kind of wrote the scene off on first viewing. Stan Winston and team's work on the various robots here is spectacular. When one softly asks another to remove its pain sensors before being dragged out in front of a bloodthirsty (or should I say oilthirsty?) crowd and torn apart I felt a lump in my throat.

It was the quiet dignity of the request that got me. If the machine had been frightened I don't think it would have gotten to me as much, but it was resigned to its fate and that moment really underlined how regressive humanity had become. The screaming crowd might as well have been cavemen and cavewomen at this point.

Yet Spielberg smartly builds this scene filled with death and destruction to a conclusion that offers a glimpse of hope. When David and Joe are taken out to be melted, the crowd doesn't see a robot child programed to preserve itself, they see themselves.

It might be the bare minimum they could do as a group of people, but they recognize what they're doing is wrong, if only because they can relate to the thing being hurt. You see the exact same behavior in people who are prejudiced against homosexuals until their brother or sister or daughter or son comes out. It becomes real then, not just some sort of “other” to be angry at.

In this scene Spielberg at once condemns and praises humanity, which gives it a complexity that I didn't fully appreciate at first glance and could very well be the last spark of kindness from human beings that we see before time and ice wipes them away.

Time was has been kind to the Rouge City sequence as well, made particularly bittersweet by Robin Williams' tragic passing. The only negative effect the passage of time has had on this scene is that Vinnie Chase is one of the dude-bros who gives our Mecha heroes a lift into the city. Adrian Grenier is fine, it's just a bit distracting.

Rouge City is the most overtly Kubrickian section of the movie as well. I've seen a lot of his original storyboards thanks the LACMA's fantastic Kubrick exhibit and you can tell that Spielberg very much stuck closely to his friend's vision here. The design of the overly sexualized neon buildings is almost parody levels of over-the-top, but it works because of the way Spielberg and Janusz Kaminski photograph it. They don't dwell on it, opting instead to throw in some foreshadowing imagery (the Blue Fairy-like neon angel at the church, for example) and get right into the Dr. Know sequence, which is smartly part riddle, part smart-ass and part hopeful.

Enough can't be said about the importance of Gigolo Joe to this section of the movie. He's so likeable that even when things are at their darkest he injects hope and lightness. I've always liked Jude Law, but I think his spot on performance here is sometimes overlooked in lieu of Haley Joel Osment's quite remarkably complex work. Law makes it look easy, but consider that he's tasked with being so charismatic while also not being as advanced as David. Joe's humanity is based in his programming while David's journey is about him discovering real human emotion.

What's amazing about the character of David in the second act is that his simple desire to be human not only achieves that goal for himself, but he also pushes Joe along as well. He inspires the robot to be more than the sum of his parts, which culminates in two wonderful little moments at the beginning of the third act.

The first moment that struck me is a great bit of subtle imagery that Spielberg gives us when David throws himself into the waters of Man-Hattan. Joe is watching from the amphibicopter and Spielberg shows Joe's concerned face reflected in the window, the falling boy drawing a tear line down from his eye as David plummets towards the water. It's a beautiful bit of symbolism.

Then, after rescuing David from the cold waters, Joe is stripped away from him. Before he's sucked up into a police amphibicopter, presumably to be dismantled in connection to the murder of one of his clients, Joe utters “I am. I was.”

Putting the symbolism of the tear so close to Joe essentially saying “Remember me” tells us that he has evolved emotionally. He desires a legacy. Joe's journey isn't as drastic as David's, but it's clear the needle has moved. It's also worth noting that his final act is to protect the boy and send him along to his Blue Fairy.

We've just about covered Gigolo Joe's part in the third act. Now it's time to turn to David.

The majority of the end of David's story is a big ol' fat bummer. He finally tracks down Professor Hobby, who he believes will be able to make him a real boy, only to discover that his mantra of being special and unique is about as wrong as wrong can be.

When confronted by another David after everything he has witnessed, our David has about the most human reaction possible: kill it.

So much of his hopes and dreams of becoming a real boy was pinned on believing he was unique. Seeing an exact duplicate of himself shatters that illusion and though he doesn't realize it the fact he gets angry before he gets depressed throws away any doubt that David is different. That new David he meets is doing what it was programmed to do, to be the surrogate child for a grieving parent. It seems like a real kid, but it's just as much a supertoy as Teddy.

It's quite a brilliant scene when you think about it. The very thing that proves to the viewing audience that David is a real boy is the thing that convinces the character he isn't. And how does he react? By moving into a stage of grief, another very human reaction.

David loses hope and throws himself off the building only to have that hope reignited when he sees the quite literal Blue Fairy.

Now to the great divide. No matter how much the person you're talking movies with worships Spielberg you can never tell how they fall on the ending of this film.

Is the final 15 minutes a tacked on happy ending or is it the closure the movie needed? That's the question. I get both sides as I've now strongly believed in both opinions. I won't call anybody stupid for thinking the movie should have ended earlier. Spielberg takes a little blame here because he uses filmmaking language to signal the film is over. The long pullback, the narration from the opening returning... he's saying “The End” visually, so when it doesn't end you're put off balance. You almost have to resettle into the movie.

I won't fight you if you think the shift is too radical, but here's where I will aggressively defend my opinion: say what you will about the 2,000 year time jump, but it's in no way a happy ending. Yes, David gets the closure he needed so desperately, but at a huge cost.

There's two ways to read the ending. The one I think they intended is actually the darker of the two interpretations. You can either say the Future Robots are lying when they tell David they can bring people back from the dead and create an elaborate illusion (ala the Blue Fairy that actually speaks with David) to give him the closure he needs or, even worse, they're telling the truth about the space time continuum storing reflections of every person who has ever existed.

For a while I bought into the illusion argument, but these last two viewings convinced me I was wrong and that the Future Robots have no reason to trick David.

I guess you could call the ending bittersweet in that case because then the interaction David has with Monica is real, but it comes with one giant condition. The process of bringing her back is a one-time thing and only lasts for a day and, as they describe it, uses up essentially the last bit of her “soul” that is documented in the fabric of space time.

In short, for David to be with his mother he has to kill her. Not only kill her, but wipe away any trace of her that's left in this universe. Even knowing all that, he doesn't hesitate.

Yes, he has the perfect day and the waterworks began falling. Some of them were happy tears. Seeing David get what he wanted and seeing Monica so open to receiving his love was cathartic after all the shit that poor robo-kid had to go through, but the inevitable finality was looming over everything as that day wound down.

When Monica, literally on her death bed, finally tells David that she loves him and he cries I was a giant mess myself. Then he crawls up next to her, holds her hand and Teddy climbs up, takes a permanent seat at the corner of the bed as the camera pulls out and Mr. Narrator comes back in to tell us that David has finally gone to the place where dreams are born and I just started fucking sobbing.

I don't use that term lightly. I was a mess and all because I bought into that bit of closure a little more thanks to my recent bonding experience with my nephew. This isn't even taking into account that it's still up for debate whether David dies when he goes “to the place where dreams are born.” I know John Williams has said he scored that moment as if he was scoring David's death, but that's actually the happier of the two endings.

The other option is he doesn't die, but becomes fully human just in time to lose everything and everyone he's ever loved. That possibility depresses me so much that I'm happy to assume he's dead, which is why I'll now start getting upset when people write the ending off as a “tacked on happy ending.” No, sir or madam. Incorrect. The “happy ending” in this instance is that a child dies before the void of eternal loss engulfs him. Yep, real audience pleaser, right?

So, I know why you're confused, but you're fucking wrong if you think A.I. has a happy ending. It's a dark fairy tale, after all.

So, that's my spiel. Thanks for reading along as I've wrestled with a bunch of thoughts on this film and on my life in general. I really hope it all doesn't come off as incredibly self-indulgent and if it did, I apologize. However I hope this ridiculously long piece has at the very least sparked something in your mind and might give some of you an excuse to revisit the film yourselves.

It's very interesting how A.I. is aging. There's still so much I didn't really touch on, like how it's a pretty rad retelling of Pinocchio or how perfect of an effect Teddy is and that I want one so bad you have no idea, but this piece was already stupid long. It didn't need to be a novella.

Thanks for bearing with me and putting up with my doting over my rather awesome nephew. Do me a favor, though. If you do decide to rewatch A.I., leave a comment about it in the talkbacks below. Let me and the rest of the readers know what you thought and if your opinion has changed, either positively or negatively. I'm convinced A.I. is a grower and am very curious to see if I'm right or just being way too sappy because I'm getting all verklempt over my own little guy in my life.

Cool? Cool. Thanks for reading!

-Eric Vespe

”Quint”

quint@aintitcool.com

Follow Me On Twitter