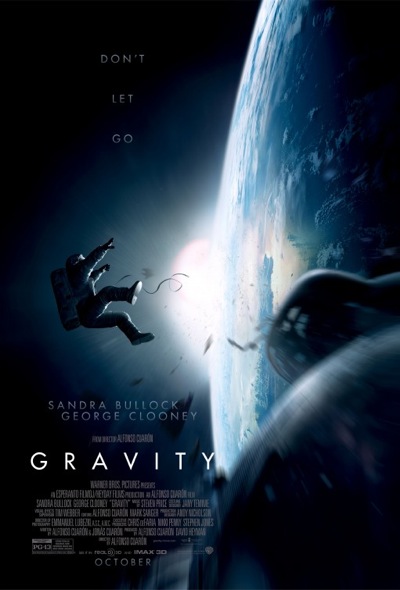

Blessed with the technical audacity of James Cameron and the visual storytelling chops of Steven Spielberg, Alfonso Cuaron might be the most talented studio filmmaker working today. He's certainly done everything in his power to prove this with GRAVITY, an awe-inspiring "space adventure" that utilizes every high-end trick of the trade to convince the viewer that they're floating in space with a couple of imperiled astronauts played by Sandra Bullock and George Clooney. Viewed in IMAX or Dolby Atmos, the film is an exhilarating reminder of why the big screen experience matters, as well as an emotionally involving tale of survival under the most dire circumstances. Clocking in at a little over ninety minutes (thanks to a tightly-structured screenplay written by Cuaron and his son Jonas), it is refreshingly devoid of extraneous backstory; for the most part, you're invested in the plight of these astronauts because you feel like you're marooned out in space with them.

Cuaron announced himself as one of Hollywood's most gifted stylists right out of the gate with 1995's A LITTLE PRINCESS. Working in tandem with his equally brilliant cinematographer Emmanuel "Chivo" Lubezki, the films have gone from sumptuous (GREAT EXPECTATIONS) to sensual (Y TU MAMA TAMBIEN) to grim (CHILDREN OF MEN), but they have never lacked for visual invention. If anything, there's been an escalating sense of daring in his movies: the erotic escapades of Y TU MAMA TAMBIEN brazenly pushed sexual boundaries, while the single-take set pieces in CHILDREN OF MEN found Cuaron pushing himself as a filmmaker. And yet it never feels like Cuaron is showing off. There's a higher purpose to his virtuoso craftsmanship; he's searching for truth, immediacy and, in the case of GRAVITY, rebirth.

As a piece of cinema, GRAVITY is a glorious experience. Moment to moment, you're transfixed by the spectacle; once it's done, you're at a loss as to how they pulled the damn thing off. All I know is that for an hour-and-a-half, I felt like I was watching a movie shot in space. When I spoke over the phone with Cuaron a couple of weeks ago, I was curious to learn where his fascination with space began, and how willing he was to compromise when the reality of the situation didn't quite conform to his dramatic needs. We also talked about the movie's masterful sound design, and how he used Steven Price's beautiful score to drown out the deafening silence of space.

Mr. Beaks: Can you point back to a moment in your life, perhaps even back to childhood, where you said, "I have to make a movie about space"?

Alfonso Cuaron: It was very early in my life. Like ninety percent of children, I wanted to be an astronaut. When I was a young child, I said, "I'm going to be an astronaut, and I'm going to be a movie director." At some point, being Mexican, thinking of being an astronaut was very unlikely, so I decided I was going to be a movie director, and maybe one day I would do a film about space.

Beaks: Before you got to GRAVITY, were you offered any space-bound science-fiction projects?

Cuaron: Throughout the years, yes, but the difference is that what I've been offered is stuff that uses space as a setting for some other thing, either a fantasy or horror, and not necessarily taking space seriously in terms of how you're bonded to it by physics and dynamics.

Beaks: In constructing the story, did you study any real-life incidents?

Cuaron: As a kid, I followed so closely the last part of the Apollo program, and going then into the shuttle years later. I was just fascinated by space. I kept following the MIR and the ISS that were put together and different missions. Then I grew up, and I started making films and doing my own stuff, but here and there still catching up with what was going on. So through the years, yes, I learned about a lot of different incidents that happened. Something that I learned years ago was what is called the Kessler Syndrome, which was proposed by a NASA scientist in the '80s. He said that the density of objects in space was so dense that any collision - because those objects travel so fast, and we're talking about satellites, probes or just space junk; tthere's a lot of space junk - will create these little explosions where hundreds or thousands of tiny pieces will go out flying everywhere, hitting other objects and creating a chain reaction. And if that would happen, around the earth would be orbiting this cloud of debris that would make further exploration or satellites impossible. That was in the '80s. That's something that, when we started writing the screenplay, I knew about. And I also knew about, a few years ago, the Russians hitting their own spy satellite and there was a fear of debris. In the last few years, there have been alerts about debris around the ISS.

Beaks: With your dedication to scientific accuracy and creating characters who must inhabit this largely realistic environment... how did you strike that balance?

Cuaron: First of all, this is not a documentary. We tried to be as accurate as possible in the frame of our feature. Sometimes, occurrences would shape our fiction. In a very early draft, we had some scenes that an expert read and said, "That would never happen." So we adapted into a completely different scenario. In saying so, I know that we're keeping certain conventions that would be very unlikely to happen in space, but we're trying to treat those while respecting the immediate laws of physics, meaning zero gravity and zero resistance. It's so complex what happens up there in terms of when you want to control something. At some point... we were honoring every single thing, but it became about that. And we wanted it to be about our characters. That was the balance that we had to keep our awareness on. There's a lot of fascinating stuff about how you accelerate and how you decelerate in space. If you want to accelerate, what you have to do is decelerate. It's a very counterintuitive situation what happens up there. In one breath, we were trying to honor all of that stuff, but it was 300 pages of just technical information.

Beaks: And it is a very tight story. It comes in at just a little over ninety minutes. A lot of this is due to the limited amount of backstory. Why did you take such a terse approach?

Cuaron: We wanted to keep as little backstory as possible, to keep everything in the present tense. This was Jonas's input. The idea was if you keep everything in the present tense, the characters become vessels for the audience's own emotions and experiences. So we wanted to limit the backstory, and whatever was the backstory to try to make it about loss - and in this case that is a child. Through our life, we all have losses. It could be a dear one or a job. It could be many things. But we defined early on that the themes of the film are adversity and the possible outcome of them as a rebirth or gaining new knowledge of ourself. We wanted audiences to be able to channel their own experience with adversity through the journey of our character.

Beaks: Knowing that silence was going to be such an integral element of the film, did this force you to heighten the visual excitement?

Cuaron: I think the visuals were always going to be like that. At one point, we did experiment with complete silence, and it was an alienating experience for the audience. We were pushing them too far away. Silence makes sense in contrast with sound, but we were clear that we didn't want to do something like putting sound in space. So the only sound that you hear as effects is whenever there is interaction with their bodies, because the vibrations would resonate in their ears. And then we took the approach of using music to convey a certain sense of energy. An interesting thing that Steven Price did is that it's music composed for surround. In other words, conventional music comes stereo right and left of the screen; here, it's a bunch of split tracks coming from every single one of the speakers, but not all of them at the same time. Sometimes it's a harmony that appears behind you and starts traveling around and converges with a harmony that is going in the opposite direction. What was important was to create an immersive experience, where you feel like an extra astronaut that is floating next to our characters.

Beaks: You're a master of staging long-playing shots. There's always something very exciting about shots like that, where you know it's a single take; it's like a high-wire act. How far in advance do you plan those shots, and how do you keep it from feeling like you're showing off?

Cuaron: I try to avoid the whole "look ma, no hands" kind of shot. There's a theory behind the shot that I work very closely with both Jonas and Chivo. There's a temptation to keep on going, and either me or Chivo says, "No, we have to cut or it starts to become about that." Here, it was very simple. First of all, with Chivo, I've been exploring for the last few films, since Y TU MAMA TAMBIEN, that character and environment carry the same weight, and it is a tension between one and the other. In this case specifically, we said we wanted it to look like a Discovery Channel documentary going wrong. If you see space exploration documentaries and footage, it's single shots. The luxury of cutting around doesn't exist in space. So we wanted to start by observing our characters on a banal mission, and we're following them objectively. Then disaster strikes, and we follow our character as she's floating away objectively. Then the camera starts coming closer and closer to her until we actually go inside the visor and the camera becomes a POV first-person kind of narrative. But then the camera starts coming out, and the intention that we had is that once it starts coming out of the visor, suddenly it's not objective or in the first-person; it's like you're a second character that is floating next to her. We were trying to create that experience as if you're floating next to them. And by the way, I cut before that. I remember Sandy saying "If we don't cut before, it is going to be about calling attention to the shot rather than following the experience."

There has never been an experience like GRAVITY. Get out and see it this weekend in IMAX or Dolby Atmos. And get ready to see it again. This is an astonishing film.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks