Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Manga Spotlight: Katsuya Terada’s The Monkey King Volume 2

Released by Dark Horse

Like Katsuhiro Otomo and Jiro Taniguchi, illustrator/designer Katsuya Terada is admittedly influenced by European comic artists such as Moebius. However, rather than the fine lines and details noted in other Euro-connect manga authors, Terada's work is remarkably fleshy. As seen in his Blood: the Last Vampire design, his style is marked by prominent human anatomy, with character that boast lips and muscle that you have to notice.

That style the perfect complement to Monkey King aims... a Métal Hurlant spirited take figure with a spiritual origin... taking a figure with gigantic cultural prominence, known for his mischievous, belligerent attitude, bestial half-humanity and phallic extendable rod, and magnify those defining features to an obscene extreme.

Journey to the West (aka Saiyuki in Japan), along with Romance Of the Three Kingsdoms (aka Sangokushi), Water Margin (aka Outlaws of the Marsh aka Suikoden), and Dream of the Red Chamber, make up what are considered on the pillars of Chinese literature. I'm probably butchering this a bit, but the general notion that I don't think I remember exactly correctly is that you introduce children to spiritual values with the parables of the Journey to the West. Teens learn politics and Confucian tenants in Romance of the Three Kingdoms. As an adult you read Water Margin, since reading its tales of rebellion would reinforce that tendency in adolescents and teens (conversely, Three Kingdoms would reinforce adult tendencies to be plotting and wily). Then, you settle down for the manners and subtleness of Dream of the Red Chamber.

In Journey to the West, the Buddhist monk Xuanzang, also known as Tripitaka or Genjyo Sanzo as the name appears in the Monkey King manga, makes a pilgrimage west to retrieve the Three Collections of Buddhist Sutras. He's beset by malevolent beings looking to gain immortality by devouring him, but he has three monstrous disciples protecting him (and for the purpose of the parables, the objects of some lessons and the instruments of imparting others) ... Zhu Bajie the pig man, Sha Wujing the river sand demon and Sun Wukong/Son Goku the monkey king.

Now, Journey to the West runs a 100 odd chapters, and a couple thousand pages in English translation. In video games terms, that's one truly long escort mission. In the many pop culture adaptations, from Leiji Matsumoto's Science Fiction Saiyuki Starzinger to Dragon Ball, it's not uncommon to try to make Xuanzang a little more interesting changing this gender. Which does win him/her some fans in some versions. (It's Bulma in Dragon Ball). Piggy and Sandy take the sidekick roles (Oolong and Yamacha in Dragon Ball) and as comic relief/long suffering second bananas win some affection. Meanwhile the violent, tricky Monkey King headlines as hero, or at least star attraction.

Probably the best remembered bit of Journey to the West is the prologue featuring the Monkey King's origin story, in which he is invited to the heavenly kingdom in hopes that station will calm him down. All the efforts of heaven to subdue him only make him stronger until Buddha takes charge of the problem, tricking the Monkey King and imprisoning him under a mountain. Leashed by a magic head-band, the Monkey King is drafted to accompany Xuanzang on his pilgrimage to India. After that, there are some adventurous encounters with the likes of Ox-King Gyumaoh and his wife Princess Iron Fan that people remember. After that, I'm guessing that most people who grew up with the story remember little and people who aren't culturally connected are more than like to come up entirely blank.

Terada's Monkey King ran in Ultra Jump, home of busty, bloody fare like Tenjo Tenge and Bastard!! In that context, the full colored depictions of ripped muscular ape man Goku savaging mythic foes is an especially vibrant expression of the magazine's niche of offering "mature" shonen for readers who have outgrown shonen. (like the rest of the Jump magazines, Ultra Jump is published by Viz part owner Shueisha, so this is a case like Gantz where Dark Horse picked up an especially outrageous manga that Viz apparently opted out of).

Outside that context, there's an essential caveats that need to come with Monkey King (beyond its testosterone soaked gender politics, explicit violent, gore, rape and so on). Katsuya Terada is a distinctive, evocative character designer and illustrator. As such, each and every of the manga's panels is an impactful image. However, he's an artist illustrating manga not a manga artist. You can say that each image tells a story, but neither in terms of plot, nor in terms fo graphic flow does Monkey King stand up well. Both are missing far too much connective tissue.

Graphically, one frame of action doesn't set up the next, such that it sometimes require a bit of backtrack re-reading to figure out how the fights are progressing. There's no question that Goku is going to come out of the fight with his adversary impaled, disemboweled, or decapitated, and specific images of that are spectacular, but without a blow and build of action, there's no impression left by the larger battle.

In terms of plot, though there is some continuity, there isn't much of an ongoing narrative. The source material doesn't help in this respect since it gets the best bit out of the way early with the Monkey King origin story, after which the series offers its particular slaughter filled reimagining of chapter long parables. And, contrary to the Ultra Jump recipe, Terada doesn't seem inclined to script the narrative into a juiced up version of the Shonen Jump formula. You couldn't really say that the chapters are failing to build on each other, because they're not even trying.

The result is that Monkey King is not a manga to sit down and read. The surest way to make this ripping, piercing, blood and guts and tits manga boring is to devote your full attention to it for more than 10 minutes. It's the kind of material that is gravy for an anthology, impactful to open up and glance at, or catch or a second when flipping through, but brutal to read end to end. Given that, wouldn't want all manga to be like this bawdy spectacle, but it's nice to have this one around.

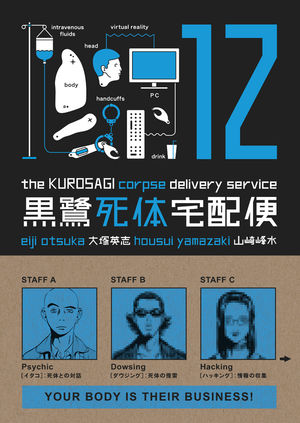

Manga Spotlight: Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service

Volume 12

Writer Eiji Otsuka

Artist:Housui Yamazaki

Released by Dark Horse Manga

Available digitally

Vertical Inc. recently licensed Tsutomu Nihei’s "Knights of Sidonia," an all-over-the-place in a good way teens in space sci-fi drama from an author known for techno-organic action horror like Blame. Nihei's earlier Biomega had a talking bear with a sniper rifle that set all sorts of comics/manga commentators talking and recommending the series. Sidonia likewise has a talking bear, and I believe the amazing absurdity will do the trick again.

It's a shame that because it's shrink wrapped... because finding a book store stocking older audeince manga has becomes a bit tricky... people can't flip through this volume of Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service.

Volume twelve's first story opens with a sequence of a couple of men wearing funny animal masks who are not-too-unwillingly seduced by a cultishly attired woman... ending up with a porn movie like scene of a bunny masked man and the woman fucking in a tree house. Add to that the next page is a man whose face and finger tips have been cut off, and the opening bit of Kurosagi 12 has the same sort of burst out the niche, bear with a sniper rifle level attention grabbing money shot...beyond being sufficiently mystifying to alert devotees of the series to the fact that they're about to read one of its highlight horror puzzlers, this winning bit also just happens to be very NSFW.

Back in the mid 00's, a lot of horror manga were getting licensed. The fact that, unlike most, Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service wasn't cancelled outright is some indication that its sales weren't entirely in the basement, but its reprieve seems largely based on the fact that it has a core of cult followers who hound Dark Horse for more releases while most other manga fans, to say nothing of genre fans, ignore it.

Also, back in the mid 00's, Kurosagi was one of the numerous horror manga to be licensed for Hollywood adaptation when that was in vogue. I'm never terribly optimistic about that sort of thing, but I think Kurosagi could have made an interesting, relevant movie then, and I think it would have make an interesting, even more relevant movie now. Considering how socially engaged it is, considering how key under employment is to its backdrop, it's really an outstanding great-recession/new normal horror premise.

Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service follows a group of five students who graduate a Buddhist university and find that their area of study isn't in terribly high demand in the work force. The fact that one is an itako (traditionally blind, traditionally female - he's neither) shaman who can communicate with the dead, and another is able to dowse for corpses, and a third claims to possess a psychic connection to an alien intelligence doesn't sweeten their job prospects. Their solution is to take some entrepreneurial initiative and create a business for themselves. The Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service will find bodies of the dead... crime victims... suicide victims and the like... and take them where they're meant to be. This brings them repeatedly into the notorious Aokigahara forest suicide hot spot, police morgues, atrocity sites, grisly crime scenes, and basically anywhere bound to be stinking and maggot infested. Karmicly this might be rewarding, but finically, it means that the cast still scramble to make ends meet with odd jobs.

Kurosagi isn't a case like Monkey King where it's best not to try to read more than a chapter at a go. Sitting down for a volume long collection of three of its stories is really far from a bad thing. But it is another case where the long, serial story isn't the emphasis. Here, it's not that the manga isn't going anywhere, so much as that it's not the appeal. It's televisual, at least televisual when TV wasn't as ongoing story minded. However, development and revelation is happening so slowly, so infrequently, with so much reticence to bring any overarching element to a head, that that character growth/reconciliation is evidently not a priority for the manga. Character histories and destinies aren't unimportant, but they aren't the focus either. What in post X-Files parlance could be called "mythology" stoories aren't what you read the manga for. Like many seinen series, the manga is developing by having the characters reconcile with their pasts. Those chapters are painful personal episodes that tie the characters to historical crimes, their own families or their nation's. Like a TV series, it's occasionally gives a glimpse into some history that makes the characters richer.

From that first scene with the funny animal mask sex, the volume's first story just gets odder and more complex, drawing in technology, cultural shifts, and esoteric psychological disorders in the convoluted mystery. The pleasure of Kurosagi is the dawning realization of exactly what you're reading. Do yourself a favor and don't study the front cover or read the back of this volume. They too much of a give away. Following the reasoning, and seeing the unfolding of what is very weird and also very considered and thought through what makes Kurosagi must read manga.

What writer (here, creative duty is split between a writer and a distinct illustrator) Eiji Otsuka does is appears something along the lines of what Warren Ellis does in some of his comics like Global Frequency or Osamu Tezuka did in some of his manga like Black Jack: take something that they read in a paper or a science journal or a cultural trend and extrapolate it out into a genre story.

Otsuka's a real knowledge omnivore, resulting in some real go-for-broke monuments of stacked topics. He knows plenty of esoteric subjects. He's on top of what's current, and, his gift is weaving together disparate subject from folklore and Japanese history to recent technological breath through and cultural concerns and stringing them all together into specific episodes of Kurosagi Corpse Delivery Service.

Manga has plenty of authors who study subjects well enough to write about them convincingly. Lone Wolf and Cub's Kazuo Koike who can create realism in his absurd manga through fascination with details and process. Famous wine manga Drops of God's Tadashi Agi (penname) is a professional writer with credits in a stack of manga, novels and screen plays. Those are all dedicated writers, but you also see the sort of dedication in plenty of other single creators who write well about a topic from a studied perspective, all the sports and cooking and food other subject based manga are filled with examples.

Otsuka ranges in and out of areas with which he had prior expertise, but what's especially noteworthy about him as a writer is his background as an editor, academic and social critic. He's curious. His creative engine certainly seems to get primed by new developments in culture and technology, as well as studies into the past. He's also professionally equipped to tease out significant factors and draw connections. It's funny the number of time that his stories pre-figure real world events. Now, while it's a coincidence that he wrote about the death of a certain world leader in this volume shortly prior to that figure's real death, it's interesting to see him thinking around something that was a credible concern at the time, which happened to become a real concern, and it's truly amazing to see the connections that he draws and threads that he ropes into the story.

There are plenty of manga that deserve to be niche or which I'm fine to see fight for attention in the crowded entertainment landscape, but Kurosagi is one that I wish would find a wider audience. It's one of the most gruesome crime mysteries you can find and at the same time one of the smartest. It's perfect for a curious reader. Otsuka weaves together relevant and/or fascinating subjects with real insight in a way that few do. If it'd takes animal masked people fucking to get this book some attention, fine by me. It's certainly not entirely inappropriate to the series.

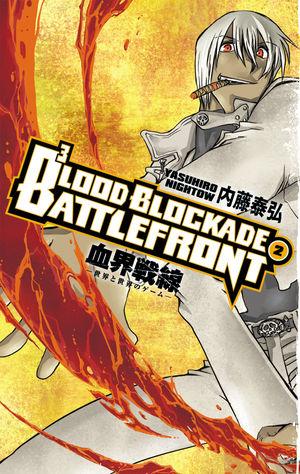

Manga Spotlight: Blood Blockade Battlefront

Volume 2

by Yasuhiro Nightow

Released by Dark Horse

Recently, while discussing his book on CPSN, Colin Powel shared a Japanese corporate executive's anecdote about being asked for directions while visiting New York City. The point of that micro-narrative, the notion of New York as an immigrant city is key to Blood Blockade Battlefront. Like Yasuhiro Nightow's earlier hit, Trigun, B3 is an immigrant story, with the western pioneer settlers swapped for a more 20th century urban take.

Three years ago, a gateway between Earth and The Beyond opened over the city of New York. In one terrible night, the American metropolis was destroyed, and rebuilt, trapping its human residents and extra dimensional creatures alike in a new paranormal melting pot rechristened New Jerusalem (or "Jerusalem's Lot"). The results are something new, which, as this second volume makes the point, pure humans are a minatory in a reconfigured city.

The point of view character, Leonard Watch, had a prior tragic experiences with a demon that gave him enhanced eyes that allow him to see the horror that still remain invisible in the occult integrated landscape. Returning to New Jerusalem, finds himself roped into joining Libra, a secret society (the purpose for the secrecy, or even why anyone is supposed to assume that they actually are secret is far from obvious), determined to keep Jerusalem’s Lot's troubles to a mild pandemonium, and on a team with violent, cigar chomping, blood weapon wielding Zap Ranfro; fanged, shaggy and intense Klaus V. Reinhertz and busty, acerbic, cool suit wearing Chain Sumeragi.

Later volumes may become more plot dominated, but these early volumes have a light novel like interest in exploring the world.

A collision of human and demonic worlds isn't terribly new or on its face fascinating. As a concept, there is little fresh here. But, Nightow does have an engaging take on it. Visually, Leonard proves to be an interesting point of view. He isn't just a newcomer demon amalgamated city, he's a small town bred newcomer to the city. Nightow suggests that the scale of the human erected place is new and alien to him. Even before it bleeds into the supernatural, he generally looks a bit lost among the glass and metal of the skyscrappers. Horror manga, most notably Akira creator Katushiro Otomo's Domu can effectively use the claustrophobic, walling in scale of cityscapes. B3 plays with horror, rather than commits to it, but it still have a particular awareness of how imposing such a place can be, especially to a newcomer.

At the same time, Leonard's mind seems very keen to cast all the extreme supernatural in a more reasonably natural light. The volume is bookended by short gags in which Leonard envisions some comely young women, then wakes up to find himself staring at some tumorous beastie vaguely shaped like some part of the antinomy of a busty lass.

The manga itself plays a similar game. It goes for big threats; elder uber-vampires that can taunt humanity by constructing crucifies out of hundreds of piled corpses, beasts that could destroy cities out of super nova rage; horrific demonic entities that can inflict eternal suffering on those who don't amuse them. But while dire, it's not serious. The darkness and destruction looking to overtake the city is always framed by chasing a monkey-like creature, a squabble among the heroes or obsession with a puzzle video game.

On one hand, Nightow pulls off the blend of light and dark, human and alien because it's not so much a balancing act as all of a piece. Like Trigun, or maybe even more-so, B3 has identity. Visually, conceptually, it asserts its own kind of sense.

On the other, the manga is a bit scrambled. B3 is a work that's intentionally a bit confused, and that's what Nightow is interested in doing. At the same time, he's never been the strongest, most coherent story teller. As much as he seems attracted to this material, it magnifies his less than completely disciplined style of illustration. Everything is frantic. Jumping between busy panels depicting busy moments in the action, it's nosy and jumbled on the border of barely coherent.

Nightow seems disinterest in, or doesn't have time for the details, given the manga where that isn't the case, B3 doesn't compared favorably. If there's a game that's central to one of B3's stories, Nightow will let play out through short hand, which looks bad next to something like Hunter x Hunter, which would invent some mechanics for the game, even if was going to come an go quickly. If there's a multi-fronted battle in another story, Nightow will cut around it, joining just in the climactic moments. Ultimately, B3 conveys the spirit more than the moment to moment development of its episodic stories, and, defying a real investment in flow of events, the net is that the manga turns out to be attention holding without really being exciting.

Especially in volume two, which is less the grand tour of the first volume and more engaged with the corners and particulars Nightow constructs a convincingly interesting world to visit in B3, but not one you want to inhabit. It's an easy manga to like and hard one to love. With Trigun, Nightow had a single, attention grabbing point (Vash the Stampede) from which he could enthusiastically build out a world. And, he really seemed to be having fun with it, down to spoofs scrawled on the insider covers of the collections. And, here it's the opposite. He has the world, and working hard, he finds plenty that is funny, exciting or spectacular, but nothing has convincingly grabbed him about it, nor had he constructed a focal point to hook the reader.

And for something more all ages...

Following a successful effort to raise funds to publish "God of Manga" Osamu Tezuka's dark, mature audience work Barbara, Digital Manga Publishing has gone to the other end of the spectrum with a new Kickstarter for the release of the Astro Boy creator's Sanrio collaboration, Unico.

In 1976, "God of Manga" Osamu Tezuka developed the character Unico for shoujo anthologyRirika, published by character goods makers Sanrio, of Hello Kitty fame. Sanrio would then feature this character in productions during the 1977 to 1985 period in which the company attempted to make anime movies for an international audience. The anime adaptation has recently been released by Discotek media.

DMP aims to raise $20,500 (they're already almost at $5,000 less than a day in) to publish the manga in a single, full color volume. They explain:

Dozens of volumes of manga by Osamu Tezuka have now come to American shores, many to great acclaim. The vast majority of them have been stories written for adults. Yet many of Tezuka's most famous characters in Japan appear in manga meant for children. We think it's unfortunate that so few of Tezuka's manga for kids are in print in English, so we set out to publish "Tezuka manga to read with your kids."

The obvious choice was Unico.

Unico is a little unicorn who possesses the magical power to help those who love him. His story begins in the Greece of mythology, with Tezuka's take on the story of Psyche. In his version, Unico brings great happiness to the mortal Psyche, who in return cares for him and loves him. But the goddess Venus is jealous of Psyche, tricking her and ordering Zephyrus, the West Wind, to kidnap and banish the unicorn to someplace far away after wiping his memory. Before Unico can spend too long in one place, Zephyrus returns to carry him away again.

Unico: "Hey, why is Venus so mean to me?"

Zephyrus: "Because Venus is the goddess of beauty, and it is a cruel thing to be beautiful."

Unico's adventures take him to the Wild West, medieval times and more, and along the way he meets kids, animals and supernatural creatures, discovering who his true friends are and transforming their lives.

Think Quantum Leap meets classic Disney, with a dose of Tezuka's unique, humane spiritual sensibility.

Tezuka originally drew Unico for Lyrica, a glossy magazine published by Sanrio, the company that owns Hello Kitty. That magazine was in full color, which means Unico is one of the few Tezuka manga to be created in color from the beginning. Publishing manga in color is difficult and incredibly expensive, so almost all of the editions of the Unico manga in Japan are in black and white. In fact, the color edition has been out of print in Japan for years.