Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

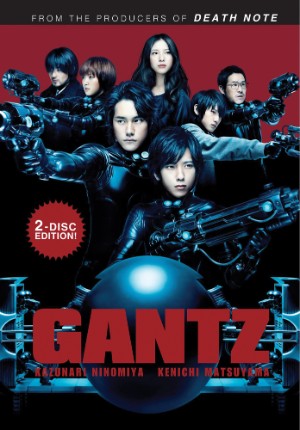

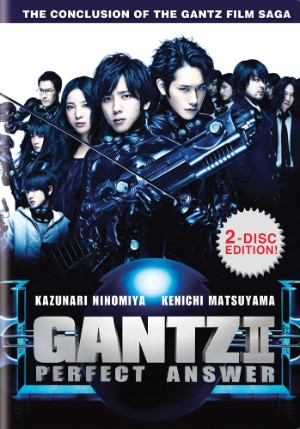

Live Action Spotlight: Gantz / Gantz II: The Pefect Answer

Released on DVD and Blu-ray by New People

Considering that I thought live action Gantz movies were a fundamentally bad idea - that films shouldn't get into a game of HORSE with a manga that aims to outdo what can be done in blockbuster movies; considering that I immediately rolled my eyes at the changes it made to the source material, I came away from the Gantz duology quite impressed. It's a frequently on the nose story that is not as provocative, nor as transgressive as the manga is in its better moments, but it does get a competent, entertaining story of regular, unprepared people dropped into superhero/first person shooter game danger out of a manga that is a serial of sensational events, which shouldn't translate across media.

The two Gantz movies maintain the manga's killer high concept and basic landscape. An unimpressive young guy named Kei Kurono bumps into long separated childhood friend Masaru Kato on a subway platform. Where once Kurono was the fearless kid who impressed his peers, he's gotten a bit stuck, not amounting to much. In contrast, Kato has grown into an imposingly tall, decisive young man. The contrast is starkly illustrated when a drunk stumbles onto the subway track. After Kato is the only one among the muttering gawkers to help, Kurono is guilted into joining the old friend, and the good deed is rewarded by the pair being crushed under an express train.

The splattered pair find themselves reconstituted in a bare apartment with a group of uncomfortable men from various walks of life, a snide looking teen, and an ominous black sphere. Kurono and Kato then watch in amazement as, cross section slice by cross section slice, a naked young woman about their age materializes in the room. One of the men observes that, implicitly except for the fact that they were clothed, Kurono and Kato entered the scene in the same bizarre fashion. Traces of blood on the young woman, Kei Kishimoto's wrist suggests that, beyond titillating the audience, she was naked due to a bathtub suicide attempt. A yakuza asshole from among the men makes some evil overtures towards Kishimoto, but a looming Kato puts an end to that.

Before the Kato/yakuza stare down can get ugly, the sphere awakens, playing morning pep music and pestering the disoriented assembly with trolling messages written on a low resolution display. The sphere then presents them a mission. They're given from fitting black sci-fi hero suits, an arsenal of first person shooter weapons, the mission to go out into the streets and kill an ugly looking alien boy, and 20 minutes to kill or be killed.

Consistent with the manga, regular, highly fallible folks are given the accoutrements and mission of a video game, then play out the dead match on familiar streets, neighborhood or parkling lots. And, the movie's inherit many of the manga's cruelties. There's the literal black box... well, black sphere, deciding and arbitrarily changing the rules by which the characters have to stake their lives. There's the more than niggling suggestion that going along with seeking and destroying these aliens might be morally dubious. And, both complexities are exacerbated by a point ladder, with scores awarded for killing the aliens, and 100 points being tradable for the resurrection of a fallen fellow player or escaping the game with its traumatic memories being erased.

While the movies take this framework for the manga, they introduce their differences in their opening moments. The manga's Kurono is a disgruntled teen - hormonal and unhappy. He hasn't done anything special, but that doesn't stop him from believing that's he's head and shoulders above the grey masses around him. On the opening subway platform, as he leafs through the pictures of bikini clad girls in a seinan magazine (not entirely unlike Gantz's publication, Weekly Young Jump), he passes nasty judgment on the commuters around him. The brutal irony is that's he's about to given a particularly violent opportunity to prove the superiority he presumes to possess.

In contrast the movie opens with Kurono repeating the words "I believe that each of us has a role in life. We all have something unique to offer; that there's a place where we can maximize our abilities." This Kurono is about four years older than the manga's. He's an earnest, if still a bit underachieving job hunting university student. The manga's thread of gut wrenching high school bullying is lost in the translation. A gentler reminder of his circumstances is a father, not absent on business as in the manga, who drops in to give this Kurono a bit of a disappointed prod. Recast as more of a sad sack than a malcontent, Kurono is played by boy band vet/singer/idol/actor Kazunari Ninomiya, who gives the character puppy dog quality. He could be the lead of anything from a rom com to an indie drama.

Older than his manga counterpart, the movie's Kato still watches over a younger brother, but the burden is shouldered in a different way. Here, he's the boy's guardian rather than a Dickensian indifferent aunt, and here, he's seen/done some shit - so, Kenichi Matsuyama (the Death Note movies' L) plays him like he's constantly in pain. It takes some suspicion of disbelief to get some of these characters out of their awkward teen years. As in the source material, shy, wannabe-be manga artist Tae Kojima is introduced as a love interest, and, personality wise, she's a great compliment to the movie Korono, but no matter how sweetly she suggests it, it's hard to believe that someone who looks like actress Yuriko Yoshitaka is going to be "invisible."

Ultimately, the movies are not entire for or against playing with the manga's adolescent wish fulfillment attack. On one hand, Natsuna Watanabe works hard as Kishimoto, a role that ask her to repeat what the character does in the manga, that's more superfluous fanservice to get the readers going than it is service the story and prompt a Korono, who, in the movie is a bit of herbivore man. On the other hand, the psuedo-Laura Croft doesn't turn up. But, perhaps a better example is how Kurono and Kato's death is handled. It's not a gorey spectacle, nor is there the notes of misanthropy display has the manga shows bystanders taking cell phone pictures of the gruesome accident.

Kurono picking up a mission, power, the ability to protect others in the small sphere of the Gantz death games and even right the damage that the conflict causes casts the movie as something of a superhero feature with more potential for tragedy.

The black sphere is an object. So, despite the fact that it declares that it will be governing their lives, despite its taunt, threats and deadly changes in mission parameters, it's hard to see it as an adversary. Basically, it's what that opening monologue describes:" a place where we can maximize our abilities." Reminders of the ancillary moral conundrums, such as the concern that killing anonymous aliens at the behest of a black sphere is asking for some nasty blow back don't detract from the focus on rising to the occasion, working as a group for mutual survival, and working the that harsh points ladder to resurrect fallen comrades. In a potentially messy plot, full of mysteries, aliens a plenty and the trope of sending the heroes against evil versions of themselves this heroic arc lends a sensible structure of the Gantz duology.

The manga took plenty of angles on its violent premise, some of which were daring, troubling, smart or deconstructive. Some of these, had the manga stuck with and developed them, might have elevated the material above a sectionalist blast for action seeking gorehounds... as the manga stands, it's great if you want transgressive violence, skippable if you don't, While it would have been welcome to see some of the more insightful approaches brought into the movie, the manga also made adaptation difficult by making a point out of meandering and blowing up its status quo. We've seen an anime series try, and ultimately fail to contend with adapting the mercurial manga. The notion of regular people working together to find the heroism that they didn't know they had is more broadly entertaining than the sharper angles taken by the manga, and it's one that the features can cohere around.

The features put bold highlights around what it believes is essential, and in that traces path that is almost a character driven, or at least character focused. The whole duology is as unsubtle as that first monologue suggests; full of on the nose moments such as a bridge between the two movies in which Korono returns to the subway tracks, and Tae pulls him up, so he can stand on his own feet. And the acting goes along with that. Everyone is very attractive and or trying their hardest to play to type. I think it's Slate that has a joke/criticism of Chloë Moretz that she plays every role as it she was declaring "I'm acting!" Gantz ensemble goes for the same pitch. Here, whether it's the pained Kato or the very attractive Tae trying to get noticed, they're doing their damnest to emote their point.

The broad, a bit dark, but also a bit goofy tone, this takes the movies past the second basic problem intrinsic problem of adaptation Gantz. The original is inspired by movies: Die Hard's vulnerable to pain action hero, Back to the Future's twists and pacing, Hissatsu: Sure Death's assassins living hidden in society and so on. The manga then used the medium's freedom from movie budgets and reduced scrutiny to build a spectacle bigger, weirder and more gruesome than the blockbusters it emulated. With a bit of charisma on the part of its actors, with a bit of a nod to the absurd, the movies jump over the large cap in what they can't do.

The movies try to recapture the action of the manga with the openly articulated intension of toning down the lad mag graphic violence for a more general audience. Because of this, and because it's budget was never going to rival Hollywood's broad sci-fi action fare, when it tries to stick too closely to the manga, it skirts underwhelmingness, its dangerous aliens and the havoc that they cause look too obscured in darkness; its heroes look like slender actors in tight black suits rather than people newly capable of super-heroic feats. Fortunately, the movies do figure out how to best navigate their mediated way. The manga hits "Oh fuck!" chords as a hulking alien claws the guts out of a group of people, or a bully starts extracting teeth, or a sociopath puts on black face and starts gunning down random people in the street, or a shape shifter is all of a sudden covered in human breasts. The manga is more of an "oh, yikes!" thrill and it embraces that magnitude. It has an old school tokusatsu love for unsubtle sound effects. The cast seem to have picked up a few pro-wrestling moves and cinematic swashbuckling flourishes, and as the action heat up, they trot these out with zeal. It's at its best when it complements the slightly violent, but not entirely serious action with foes that are both dangerous and fun, such as the Tanaka bots - robot shell boys with bowl cuts and Kazuo Umezu style red and white striped shirts, that rocket around a parking lot, spitting out deadly blasts from their mouths.

The original Gantz was built around what could be done in manga, both in of terms visual storytelling, and ability to really attack what an audience of young men might looking for. Making a movie out of it certainly didn't seem impossible, but, it did seem besides the point and otherwise destined to be underwhelming. In practice, Shinsuke Sato's Gantz movies lacks some of the manga's interesting acerbic spirit, had some superfluous bits, and had some trouble chasing too closely to the manga, yet still they got a solid arc, with a sufficiently endearing lead and fun set pieces out of the endeavor. That's so much more than I thought you could hope for from a Gantz movie that I can't help but be impressed by the duology.

Manga Spotlight: Dororo Omnibus Edition

By Osamu Tezuka

Released by Vertical

Three years after their prestigious Eisner Award winning publication of Osamu Tezuka's Dororo, Vertical has collected the three volume manga in one gargantuan omnibus. This comes coincidentally weeks after the revelation that The Fast and the Furious: Tokyo Drift director Justin Lin is developing a Hollywood adaptation of "God of Manga", creator of Astro Boy and Kimba the White Lion, Osamu's Tezuka venture into the territory of the dark and strange.

The title, "Dororo" is a childish mispronunciation of doronbo or thief, and actually refers to the manga's spunky young sidekick. modern versions of the story, especially the 2007 Japanese live action adaptation, focus on the character's tragic past, in the classic, 1967 boy's adventure manga, the mischievous young thief's role is spirited counter-point to the story's grittier protagonist, Hyakkimaru, as that swordsman wages a personal war against the things that go bump in the night.

Hyakkimaru, whose name roughly translates to Child of 100 Demons, is a physically ravaged swordsman in the tradition of the heroes of Blade of the Immortal or Berserk. His story opens with a war lord prostrating himself in a demonic temple and promising its infernal statues any prize in exchange for victory in battle. A newborn mouse falls onto the floor of the temple, inspiring the lord to promise the body of his soon to be born child. So, on a bright morning, with birds chirping, the lord's wife gave birth to a child with 48 body parts taken by the demons. Noting that the child lacked eyes, nose, ears, and limbs, the lord is overjoyed with the realization that the deal had been consummated. The most that the grieving mother could do for her son is put the newborn into a basket and let it float down the nearby river.

The basket is found by a doctor, who further discovers that the baby's super human will to live is so strong, he can find food without the help of any normal senses. The doctor further aids the boy that he names Hyakkimaru by creating a prosthetic body. However, their happiness is broken by the demons drawn to the doctor's hut by Hyakkimaru's presence. Before the slobbering nasties and rock throwing imps can drive out Hyakkimaru, the doctor outfits his arms with a pair of swords, with which he can recapture his human body from the demon.

Beyond their importance in shaping the landscape of modern manga, a large element of what makes Tezuka's manga still worth reading decades after their original publication is the complexities of their multi-faceted nature. Tezuka could write for young audiences while incorporating hard aspects of his humanistic world view. He could address light entertainment with dark edges and bleak stories with moments of perseverance and optimism.

Dororo was a boys' manga series, and, more than that, it was one from 1967. Modern, post war manga wasn't that old at the time. Writers were just starting to think about the possibility of children growing up reading manga and growing out of young audience stories. As such, young readers were still the primary audience for Dororo and Tezuka hoped to engage them by playing to fascination with monsters and the grotesque. In this, he was following the path laid out by Shigeru Mizuki's still phenomenally popular horror adventure Graveyard Kitaro. "Dororo" as much as tips its hat to Mizuki in its dialog. What Tezuka brought to this was the grand, cinematic vision that helped establish his fame. Here, his visual ambitions yield literally awesome set piece battles with giant demon sharks, possessed subterranean statues and nightmare ghost horses.

Dororo was an adventure written for young audiences, from a time when you didn't get sprawling, developing manga series like later shonen serials, with a notoriously abbreviated ending. Yet, there is more than enough sophistication to what Tezuka was writing to satisfy modern and mature audiences.

The manga is set during the Sengoku or "period of warring states" that ran from the 15th to the 17th century. In the absence of a strong central government, Japan fragmented into contesting ruled domains. Crucially, in Dororo, the supernatural beings that took Hyakkimaru's body and haunt his adventures aren't the chief cause the era's acute human suffering. They're its reflection. In this, Tezuka spins his ghost stories into dark political parables, such as the powerful "Banmon, " about the haunted wall at the center of disputed territories that can stand in for any number of real world conflicts.

This provocative complexity is further underscored by the irony of Hyakkimaru's quest. As he trades a pieces of the artificial body that make him an effective warrior for more fallibly human pieces, his experiences with wars and suffering bleeds him of his once super-human attachment to life. Though an adventure written for young readers, Dororo is far from simple and disquieting as often as it is exciting.