Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

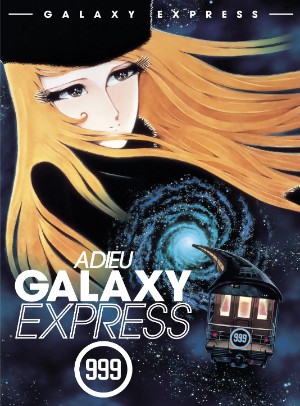

Anime Spotlight:

Galaxy Express 999

Adieu Galaxy Express 999

Released by Discotek Media

Galaxy Express is a space opera in the truest sense of the term, and from anime and manga's king of space operas, Leiji Matsumoto (Space Battleship Yamato, Space Pirate Captain Harlock). Though not a dead genre in anime/manga, it's one that now only makes its presence felt every couple years with the occasional, interesting non-success (see Heroic Age or Glass Fleet). Factor in the particular narrative, design and philosophical characteristics of Matsumoto's work, and you get a pair of anime movies from 1979 and 1981 that seem anything but current. In Japan, Galaxy Express 999 remains a landmark. Its willowy, to steal a line "Doctor Zhivago-lookin' shiksa" Maetel is basically a national totem, no less recognizable than Darth Vader is in North America. Every few years, 999 inspires some media-making tourism campaign or pachinko launch. While a beloved classic, anime and manga have drifted away.

As far as North American anime watchers go, divorced from their entrenched cultural position, the movies' age and nature leads to the question of whether they're dated or still appreciatable classic.

The core of Galaxy Express 999 has a mythic essentialism to it. Basically, a boy travels into mysterious distances with a beautiful surrogate mother/object of confused desire in search of immortality and revenge against the man who killed his birth mother. Far from missing or ignoring the Oedipal potential, it fully realizes it.

The epic is set in a future where fully biological humans are an underclass to a wealthy elite who have cast off their bodies in favor of an undying robotic existence. An ugly potato-ish kid in true Matsumoto form, young Tetsuro Hoshino lives a hardscrabble life, with a mother whose lithe beuaty transcends the near desolation in which they live. He hopes to comfort her by sharing his dream of acquiring the money needed to purchase a ticket to the Galaxy Express 999, an interstellar train that will carry them to Prometheum, the planet that dispenses robotic bodies. Then, tragedy strikes, when, on a snowy night, Count Mecha descends on Tetsuro, killing his mother and taking her body as a trophy.

Tetsuro matures into adolescence with a group of urban orphans, and with their help, in a scene of youthful movie orphan exuberance, he attempts to heist a boarding ticked to the Galaxy Express 999, still aspiring to get onto the 999, but now of hoping to use a new robot body to take revenge on Count Mecha. The robot Gestapo catch him in the act and commence hunting down Tetsuro. They would have killed him, if not for the timely intervention of blonde, black fur clad mystery lady Maetel, who takes him into her hidden lair. After pretty much showering in front of him and carrying on a mysterious conversation that suggests some duplicity, she favors Tetsuro beyond saving his life, taking him on board the 999 and guiding him on his journey.

Galaxy Express packs on a lot of baggage, but it also demonstrates an awareness of the weight in that it does not evoke lightly or accidentally.

In terms of it's span, the original 1977 manga went 21 volumes, with runs in Shonen Big Comic as well as its adult audience label-sibling. The 1978 TV series ran 113 episodes. In addition to featuring multiple journies, it managed to fill that expanse with a rule that the 999 must stop for one local day at each station on its route, peppering the stars with planetary stops for Tetsuro and Maetel to step off and encounter different speculative societies, forms of life and perspective on replacing biological existence with mechanical.

For the most part, the movies keep these possibly digressive sidetreck to the essential, such as a melancholy stop on frozen Pluto, where original bodies of the mechanized are mournfully locked away under ice.

The "Paradise Law" anarchy of terraformed Mars comes closest to going off the track, especially since it is introduced, then under resolved, but the visit to Mars serves as an exercise in another way in which Galaxy Express 999 tethers itself to something grand. As well as exploring the universe, it explores the Matsumoto-Verse.

The pantheon of Leiji Matsumoto-created space heroes is not subject to narrative consistency. Galaxy Express puts itself adjacent to the various stories of black clad, skull emblazoned freedom fighter Space Pirate Captain Harlock and his space zeppelin/galley pilot female counterpart Queen Emeraldas, their stumpy but valiant companion Tochiro, and the millennial queen Promethia. Despite through lines, you're never going to construct a coherent time line for these characters.

However, there are fundamental principals that concern the various space operas. Reoccurring motifs reinforce each other, cementing a landscape of the universe. With their moral implications, they become Matsumoto's version of slaying a dragon or caputing a unicorn. For example Captain Harlocks's would-be aviation nemesis The Owen Stanly Witch shows up again in the middle of space as a part of a Scylla and Charybdis, and it is a it of reuse, but, additional instances of the vortex also suggest an operating law of Matsumoto's cosmology.

These figures like Harlock and Emeraldas who blow in and out of Galaxy Express 999 similarly serve to personality elemental laws of the universe. These are folks who raise sails and fly their banners in the vacuum of space. The guys whose existential determination supersede physics. And, they define the parameters that Tetsuro is measured against.

This vehemence marks Galaxy Express 999. It's anime that is not just rearticulating values that come along for the ride with the genre. Not just form, it's a vocal declaration of belief.

In a recent interview, "next Hayao Miyazaki" Makoto Shinkai answered a question about his next project saying

ust two and half months have passed since “Children Who Chase Lost Voices from Deep Below” was released in Japan, so I haven’t had any time to think about my next project.

One thing I can tell you for sure is the March earthquake in Japan changed the way I think about daily life. I used to try to capture everyday moments and their special meanings in my works but I’ve realized that things change every day for many reasons. Because of the earthquake, many Japanese people had to leave their homes. That is incredibly sad and tragic, but I want to find something positive in the sadness. So I’m thinking about doing something about leaving home but from a positive point of view. How to weave that into the story is my job as an animator.

This is a director who made his name with self-produced Voices of a Distant Star, about text messages between teenage couple separated when the girl travels into space at relativistic speeds to go fight a war. I imagine that the shift Shinkai intends for his work will reflect the general effect of the earthquake on anime/manga related media. It may not always be entirely discernable, but themes that were being evoked will now be constructed with reality in either the foreground or background of the minds of the media's creators.

Notions of destruction, tragedy and perseverance are prevalent throughout anime, but in recent decades, as anime became a field of dedicated fans creating anime for dedicated fans, these themes largely became extrapolations of earlier works in the medium. You'll find fewer recent works that considered what military service means than you will works that consider about what military service meant in Gundam. And, you'll find fewer works that consider the dynamic between radical political movements and government authority than you will works that evoke a bit of what was done by Katsuhiro Otomo or Mamoru Oshii.

It's not that Galaxy Express 999 isn't itself a response. It's a very traditional heroic quest, and it wound up looking to another essential hero's journey/space opera. Adieu was released a year after Empire Strikes Back, and it's incredible to think that often chambara inspired Star Wars didn't loop back and make a big impression on Matsumoto's work.

Even it's primary image is not a unique motif. In anime, a train's progress into the ethereal realm, whether it's the Galaxy Express 999 or the railway in the latter act of Spirited Away is inexorably linked to poet/children's author Kenji Miyazawa's landmark Night on the Galactic Railroad, the way that a talking animal divinity is inexorably linked to CS Lewis' Narnia books.

Matsumoto has a way of appropriating symbols and making them his own. The classic example of this is how Harlock's skull and bones is not a traditional pirate's warning of mortal peril, but instead is a declaration of the willingness to struggle until bleached bones are all that remain.

In the case of Galaxy Express 999, the iconic Maetel is inspired by the actress Marianne Hold... or she's an evolution of Starsha, a character Matsumoto drew at age 17 inspired by a portrait of a neighbor named Takako Mise who was the granddaughter of Philipp Franz Von Siebold, a Dutch doctor who was the first European to teach Western medicine in Japan during the Edo period.

Origins are complicated by Matsumoto's mutable accounts, but what's certain is that his works are inspired by the experience and not simply the sediments laid out by other's early stories.

Leiji Matsumoto was born in 1938. His father served as an air force officer during the war, and visions of the sky and beyond maintained a special significance in Matsumoto’s imagination.

After the war, trains were one of the few functioning systems in the profoundly damaged Japan, and that made an impression on Matsumoto. And, after a childhood of sketching manga inspired by American cartoons, HG Wells and Japanese sci-fi author Jyuza Unno, and maturing in the difficult living of the post war era, after watching a "For Tokyo" train for years, Matsumoto pawned his possessions, bought writing tools and a ticket and went to Tokyo to establish a career as a manga author.

Born in 1941, Galaxy Express 999 director Rintaro is of an age with Matsumoto, and the echoes of profound destruction similarly resonate through his prolific career, in works like Doomed Megalopolis, X, Metropolis, and Harmagedon.

The result is a rich fairytale with an genuine spirit, and that elevates the material. The first movie allows Tetsuro to be a kid. He's determined, but he's also impulsive and reactive. He tests rather than thinks. He does things bound to aggravate an adult watcher and at the same time, the movie gives him not only opportunity, but deference. Everyone sees a hero in him. However, the rationale doesn't simply seem to be favoring the kid hero to connect to a kid audience. There's a discernable, appreciatable point of view. The Matsumoto quotient distinguishes the parable, and your mileage may vary as far as how much as you're given to liking a hero's quest into the stars, but if you want media with distinguishing characteristics, you need to watch Tetsuro's travels towards the ideals of Harlock and Matsumoto.

Adieu's climax has some unsatisfying flaws. The Star Wars parallels are an issue. It builds to a fight scene that may have been from a primordial age of video games, but which is still unfortunately video-gamey. Still the foundation of Adieu has pressure on the chest power. This time around, Tetsuro is aged to a point where he's old enough to take responsibility ,but young enough not to be worn down by experience. More than that, the movie puts a terrible weight on his shoulders. As it opens, it finds him with fighting with and losing adult comrades on a battle ravaged planet, It comes to imply that he is, or is effectively, the last child of Earth. Then, as he explores the universe again, and finds not just sadness and anarchy, but industrialized processing human bodies. This is anime from people who have seen desvistation, produced on a large scale with a large budget. When they stop to take a long look at the consequences of the trouble laid out in the previous movie, the visions with which they fill the screen are potent.

I wouldn't be surprised if there were anime gurus out there who could name every anime movie made by a major producer. There aren't that many anime features like the works of Katushiro Otomo, Hayao Miyazaki Isao Takahata, Mamoru Oshii or Satoshi Kon. There aren't many secret gems that you wouldn't have heard of if you spend much time reading about anime. But, factor in the cloud of lesser anime movies... There are some bad ones out there, and sometimes it seems like most of the ones not by the acclaimed masters have serious problems, especially in the scripting, especially the way that they erect rickety plot bridges to connect set piece islands. And factoring that in, apart from popular franchises that turn out movies on an annual basis (One Piece, Naruto, Bleach, Pretty Cure, Crayon Shinchan, Doraemon), there still has never been that many anime movies produced. OVAs came and largely went. TV production boomed and settled, remaining the chief focus of anime production. But, the economics of making anime movies have always been a risky venture.

Rintaro doesn't always produce entirely successful work, but as someone who has directed a considerable share of those movies, he is an important figure in anime. Magnitude is one of his specialties and with a work like Galaxy Express 999 he can produce something spectacular. Coupled with Matsumoto's mindset, he produces an interestingly distinctive experience with Galaxy Express 999. With Adieu, the contest between bleak and hopeful visions creates something classically powerful.

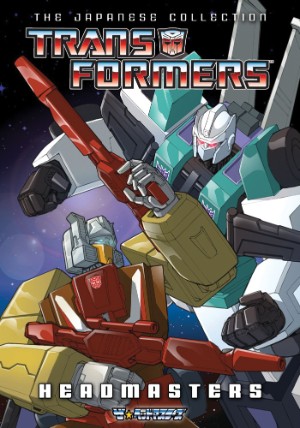

Anime Spotlight: Transformers: The Japanese Collection

Headmasters

Released by Shout! Factory

North America got the Headmasters toys, ones in which the cars, helicopters, and alligators had little pilots that transformed into the robot mode's heads. And, the American Transformers show closed down with a three episode story that introduced Chromedome, Highbrow, Skullcruncher, Weirdwolf and this company.

However, 1987's Transformers: The Headmasters was the first of a trilogy of Transformers shows, also including 1988's Transformers: Chôjin Master Force, and 1989's Transformers: Victory, that were never broadcast in North America. These series, in which Takara took the franchise in a Japan-exclusive direction, have been collectively referred to by fans as the "Takara Transformers."

The Japanese in-story origin of the Headmasters is different from the American one, in which Spike Witwicky teamed with Cerebros, who in turn Transformed into the head of the battle ship, Fortress Maximus, and alien Nebulons became the heads of the other new Transformers.

The Japanese origin of the Headmasters is one of the more intriguing elements of the show. Four million years ago (the series is set in the far future year of 2011), a group of tiny Cybertronians flee their war torn planet. The refugees crash on the planet Master and its harsh environments takes the lives of many until the survivors develop larger Transtectors bodies to connection to.

(The back of the anime's box uses the Japanese naming conventions, featuring Convoy and his Cybertrons versus the Destrons, but the English subtitles, there's no English audio dub here, uses the American naming conventions. So, Cerebros, rather than Fortress is the subtitled name of the robot who becomes the head of the giant Fortress Maximus).

The anime manages some interesting moments regarding the divergent perspectives, such as the Autobot aligned Headmasters getting a bit more angry than you'd expect from most of the non-dinosaur based members of the heroic faction. Yet, this is not exactly a brilliantly written toy commercial. You've heard of machine intelligence? Well, Headmasters manages machine stupidity. New wave of toy/characters will show up mid-series, such as the Horrorcons: gorilla Apeface and ghidorah thing Snapdragon. The characters will act confused, engage the new character, then, mid confrontation, all of a sudden remember their log history with the new characters. "Wait! We knows these guys. Remember that history we had together on Planet Master..."

It's not the most mature, sophisticated genre, but I will admit that I remain a fan of giant robot anime. Super-heroes don't do it for me unless the action is really good. Pro-wrestling seems kindof interesting in the abstract, but I can't get into actually following it. You're not going to catch me watching NASCAR. Probably because I was imprinted as a kid by Transformers and Voltron, as colorful power totems go, it's pretty much just giant robots that commend my attention.

Chuck Klosterman said of "guilty pleasures"

People who use [the term "guilty pleasure"] are usually talking about why they like Joan of Arcadia, or the music of Nelly, or Patrick Swayze's Road House. This troubles me for two reasons: Labeling things like Patrick Swayze movies a guilty pleasure implies that a) people should feel bad for liking things they sincerely enjoy, and b) if these same people were not somehow coerced into watching Road House every time it's on TBS, they'd probably be reading A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man.

I'm a consistent "guilty pleasure" denier, and yet, I'm not exactly proud of the fact that likes giant robots do the trick for 30-something year old me. I'll at least sample just about any giant robot anime.

So, take it from a guy who has watched more than his fair share of this genre, if you're looking to recapture some the buzz you felt as a child watching Optimus Prime lead teams of cars and dinosaurs against Megatron's jets, tape decks and ground shaking mini-robots, you can do better than Headmasters. Go for the operatic spectacle of Giant Robo. The second quarter of the series is a real, repetitive rough watch, but GaoGaiGar is like the great Transformers series you never knew existing. New Getter Robo has a crazed, ass kicking spirit.

In the case of Headmasters, I can almost picture Keisuke Fujikawa, a writer on a lot of the Leiji Matsumoto anime, including Space Battleship Yamato/Star Blazers and a bunch of Galaxy Express 999, rubbing his eyes, trying to figure out how to write all these toys in and out of their planet hopping war.

There is some consistency to be found. Usually, at a point or two in an episode, the Autobots Headmasters will manage to display some personality. Decepticon Emporer Galvatron is a dangerous nut, but there is a core of follower such as Cyclonus and Scourge loyal to him, while new rival Scorponok shows himself to be a black hearted schemer. Beyond that, it's all up for grabs.

Spike's son Daniel is a constant presence on Headmasters, least you forget that you're watching a kid's cartoon. He and child Transformer Wheelie constitute some platonic distillation of the annoying kid character, eager to get in the way, prone to pranks and tantrums. But, in practice, Daniel doesn't have much of a consistent personality beyond a fit-to-the-circumstance child. One episode he's hardly phased when being attacked by the Godzilla sized Trypticon, but before long, his bravery is being questioned (the Headmasters are always good for questioning other hero's fortitude) when he's deathly affraid of the much more boring challenge of going into space to deal with an asteroid.

Daniel's inexplicable shifts between fearless and frightening are a manifestation of a quality of the show that isn't going to sit well with an older viewer who isn't simply transfixed by the bright colors and thunking robots.

Giant robot anime evolved along two, rarely entirely distinct paths. You have the "Super Robot" subgenre (robots that are not bound by the laws of physics, for example, a machine given strength by the protagonist's heroism) and the "Real Robot" subgenre (robots created with some sense of speculative realism, including elements like limited ammunition or power supply.) In the former, shouting or willpower might character the robot, but that doesn't mean that a compelling super robot show is going to be arbitrary.

Despite some rituals, particularly relating to Cerebros' transformation into the giant Fortress Maximus, Headmasters is a profoundly arbitrary show. Particularly once a battle is engaged, random characters will show up, everyone will start hitting each other, and there's no sense what will decide the conflict. Two characters square up, repeatedly blast each other, and if the engagement isn't simply called off, after landing some random count of ineffectual hits, something may prove damaging, or even in a couple of cases, fatal ("fatal" being until the character/toy is replaced by a new color scheme/redesign). Maybe this unpredictability is preferable to a more entrenched formula, but this is a show about robots at war... when it defies getting a handle on how the conflict is supposed to play out, it's difficult for excitement or drama to develop in the robot rockem sockeming.

Even as the genre goes, it's far from top tier. Previously mentioned GaoGaiGar is a toy commecial based on a Takara line, but it's a passionately constructed, bombastically entertaining one.

Still, Headmasters is far, far from meritless.

There is the nostalgia value of seeing a toy that remember owning in animated action. I had the helicopter Headmaster, Highbrow and certainly smiled a bit when he got some screen time. And, more generally, the notions with which it works are a nice time capsule for an 80's toy geek to open up. A cross over with Battle Beasts is icing on the cake.

The filminess of the show works in its favor in some respects. I don't want to fall back on "so bad its good, but since Headmasters isn't great, wonkiness becomes its greatest strength. It's a chance to smirk at past innocence. While not as painful as the worst of Thundercats or He-Man, it still affords an opportunity to sit in stunned amazement at what you would have thought was solid entertainment in your youth.

Ultimately, it might be best enjoyed ironically. The show's end credits have Spike and Daniel trying to do tandem pantomimes of the Headmaster's vehicle modes. It's difficult to take this too seriously. In particular, Headmasters reflex reaction to misfortune, tragedy or cataclysm is generally to get really weird. Basically, the anime is at its wonderfully strangest when its trying to establish the significance of an event.

In episode two or three, Blaster and Soundwave destroy each other in one of those exchange of attacks that inexplicably goes from ineffective to devastating. Both come back shortly in even more gaudily colored reconstituted form. During Blaster's brief time in Robo-purgatory ,Hot Rod assigns the Autobot tapes a mission to go spy on the Decepticons with the aim of ferreting out the secret weakness of their new Madmachine WMD. And the cassettes that turn into lions or human sized robots are sitting around sulking over the death of their senior partner. You've never seen something sadder than a depressed robot rhino. So, then the other Autobots, particularly the Headmasters start calling them cowards, The best part is when Hot Rod stops, with a look like he just remembered something and promises that they'll revive Blaster, then he gives the camera a look like "wow, these assholes are really going to believe me."

In another weird turn from tragedy into celebration, starts with Scorponok setting off a series of bomb tha render Cybertron a burnt out husk. The main Autobot leadership deal with this by traveling into deep space, leaving the Headmasters in charge. The transition is marked with a party that climaxes with the tank Headmaster getting drunk and badgering the tape player Autobot into playing karaoke.

Headmasters is probably going to be one of the best selling mecha anime in recent years. And, given that there's plenty of pleasure to be had in a collection of 35 episodes of regularly amusing robot fights that retails for $35, I don't feel too bad about its success, or even about recommending it. I would however point out that if you want a real testament to the fun that can be had with the animated exploits of mecha, you can pick up a collection of Giant Robo for all of $15. Yeah, there's value in Headmasters' tie in to a toy that you know and maybe love, but there's fun to be had in giant robots that aren't simply being featured in route episodic commercials.