If you only see one movie this year see “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs”. There’s nothing like it. It’s the best film I’ve seen since “Wolf of Wall Street”. The Coens have given us at least a couple of great short films in the past (their entries into “The to Each His Own Cinema” and “Paris J’Etaime” omnibuses were classics) and Ethan Coen had his “Almost an Evening of one act Plays”, so it should come as no surprise that the Coens have a small backlog of short film scripts. They’ve produced six of these in this lavish collection framed as a book called “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs and Other Tales of the Frontier”, a Louis L’amour-esque volume complete with fully written pages and illustrations accompanying each story that manage to underscore and enrich the films they accompany. The stories have no narrative through-line, though the stories do manage to work as a progression of mood to a feeling of conclusion. The Coens havelikened the different stories to tracks on an album. In that spirit let us look at each story, chapter, song, and bullet in the six-shooter separately.

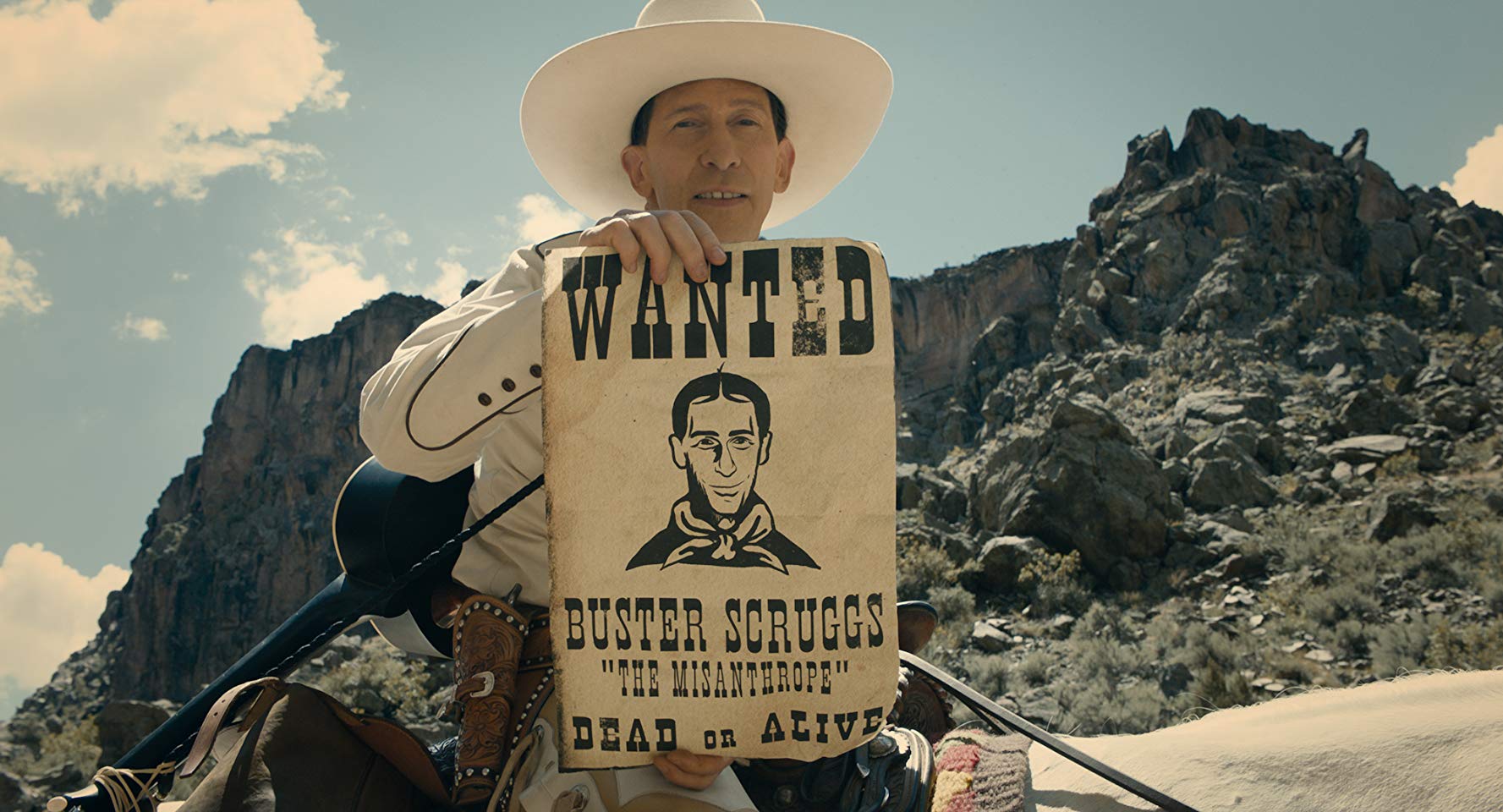

Chapter 1: “The Ballad of Buster Scruggs”

After hooking you with the marvelously shot opening bookend that assures us that this will be as meticulously made and beautiful as anything the Coens have done (they have not taken Netflix’s money and run), they kick off in the most weightless of the stories with Tim Blake Nelson in the role of a lifetime as a singing, highly skilled gunslinger who finds constant challenges to violence when he reaches a town. It is comedy gold and the most gleefully bloody thing the Coens have done. A lot of critics have likened this to Peckinpah meets Roy Rogers, but this one has notes of all kinds of things, Tarantino, Bugs Bunny, Terence Hill, and for me the funniest part was the tone of Tim Blake Nelson’s murder virtuoso’s dialogue which called to mind the first person narration of Jim Thompson. This story is like listening to Alex Chilton do Volare, and it’s magically light, a short Hudsucker-esque shoot-em-up.

Chapter 2: Near Algodones

This is the James Franco story with the very funny line from the trailers. I’m going to spoil this one completely because I’m still working through it and the trailers have already blown the payoff. Franco is first seen approaching a bank. Our first look at his face is one of the most memorable images in the film. A review called the cinematography of Scruggs ‘hyperrealistic’ and for damned good reason. We see every pore on his face in a way that feels beautiful and strange. This is an odd bank with only one teller played by the beloved Stephen Root. Franco’s hold-up of Root was perhaps my favorite scene in the film, it had great action, detail, and Root running wild with endless dialogue. The heist goes awry and Franco wakes up in a noose with his sentence about to be carried out in before being delivered from his jury by a Native American (Comanche I think it was said) attack. This is another amazingly funny and action-packed scene. Both of these skirmishes rate with the action in “No Country for Old Men” in quality, however, audiences may note here that the Native Americans are only portrayed as faceless marauders in this picture. This is a movie uncommonly populated, especially in roles of agency by pale-faced men. This occurred to me in three of the stories. This was the first. Back to the story. Franco gets left by the Comanches to be found by a lone cattle driver who rescues Franco, takes him on, endlessly bends Franco’s ear, then runs away when men are spotted on the horizon. Franco doesn’t run and is convicted of rustling the cattle before being promptly hung, this time for real. This story is also quite light, and perhaps we are to take it easy in the vein of it’s dim protagonist, but it also felt somewhat unfulfilling at the end. Guess what? I still loved it. It was filled with laughs and Franco, the modern Nicolas Cage, fits right in with H.I. MacDonough in the Coen dim doofus hall of heroes. Odd film but fun.

Chapter 3: Meal Ticket

Through these first three frontier stories the movie really does resemble an album or Western mix-tape. There’s an upbeat rocker, an even rockier rocker, then comes track three where things slow down and get heavy. And boy is “Meal Ticket” heavy. And dark. It’s a Flannery O’Connor tour de bleak about a traveling orator deprived of his arms and legs played wonderfully (this film has so many brilliant performances it’s a wonder one doesn’t lose track of them) by Harry Melling and his caretaker and impresario Liam Neeson as perhaps the most awful human ever conceived by the Coens. I won’t give away details of this one, because the plot is the thing with it, but I was taken by the way this story took its time with showing the act in different cities and the repetitive nature of traveling performance. Often in modern movies, one feels resolutions are unearned and isn’t sure how the problem could be fixed. One solution we’ve forgotten that was employed by films like “All the President’s Men” is slow repetition, a technique we’ve kind of vilified as self-indulgent and ineffective in film. This chapter feels the most like a classic short story that would be just as effective in print as on film, but that would discount certain pleasures like the way the Coens have cast the biggest star in the picture and how they reveal him.

Chapter 4: All Gold Canyon

This feels like the tail to a coin with ‘Meal Ticket’ as the head. The cold winter nights of the Neeson chapter are traded for lush, bright mountain country with Tom Waits, an actor who instantly inspires love in the way of a Stephen Root, as a solitary, old gold prospector, working every day, singing, talking to the sun, and taking in the local wildlife which includes a big buck straight out of “Shane”. Like “Meal Ticket” this story features fairly languid montage of routine; watching Waits work and not give up, the song never leaving his heart. It’s insane how effective it is at making you want him to succeed. No backstory no conflict except that we feel this old,hard-working man deserves good things. There is a dark twist to this story here, and there may be no more vintage Coen bit of gore than watching a wound slowly soak a shirt with blood. This one had me exclaiming to the movie aloud things like “Fuck yeah!” and “Oh no!” Higher praise I do not have.

Chapter 5: The Gal Who Got Rattled

I believe this is the longest and the strangest of the chapters. It begins with a long, unsettling dinner scene before Zoe Kazan as the titular Gal and Jefferson Mays as her brother set out with a wagon train on the Oregon Trail with their dog, cutely named President Pierce. This one reallyluxuriates in nature photography, the sky, in particular, this time, a sky maybe just a little too big for the nervous Kazan. Kazan’s character seems particularly out of place as a heroine in 2018 (she kicks zero ass and is very reliant on men), and we get another bloodthirsty native attack in this one, but the strangeness I refer to is in the shape of the narrative, and that Kazan is by far the most famous of its cast. This is a cold story that recalls Peckinpah and Cormac McCarthy and builds quite slowly. There is repeated mention of President Pierce’s incessant barking, but we seldom hear barks. Kazan may not be the most important character in the story, and what was up at that dinner? The action climax is amazing and the ending is a pip. You’ll wonder where this one is going almost up to its final beats, and you won’t be disappointed. Shout outs to Bill Heck and Grainger Hines, who probably still can’t believe they got parts this good.

Chapter 6: Mortal Remains

Scruggs closes with a shorter piece that could easily be a play about five passengers on in a stagecoach journey. The passengers are Brendan Gleeson and Jonjo O’Neill as two mysterious men transporting a body, Tyne Daily as a religious woman on her way to her estranged husband, Saul Rubinek as a French bon vivant, and Chelcie Ross (yet another revelation) as a fur trapper. They talk of love, morality, life, death, and entertainment. At some point, you realize the twist and think you’ve outsmarted the Coen Brothers on this one, but it turns out you’ve only figured it out exactly when they want you to. What seems like a dark ride is really just a chance to luxuriate in Coen Brothers dialogue, wit, and control. The story ends with Rubinek giving a perfect grace note telling us not to care too much, life and death are life and death, let’s just have a good story.

And here we have six good stories and so many more great beats, lines, scenes, characters, shots, and moments. The Coens continue to give us much. Here they have given us their best film in years.

-Deckard