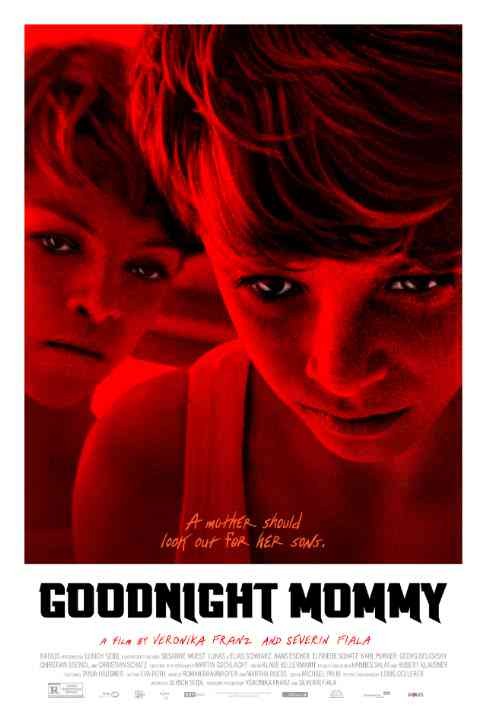

GOODNIGHT MOMMY is most certainly a horror film. It is also Austria’s official submission for the Best Foreign Film Academy Award.

The film, which first opened in September, is the chilling, moody story of two twins, Elias and Lukas (real-life twins Elias and Lukas Schwarz), who have spent some time by themselves in their nice, modern house in the woods. When the story starts, their mother has just come home from a major cosmetic surgery; you may have seen her bandaged face, as it’s the prominent image of the marketing. There’s something off about their mother, beyond her new looks. She’s violent and harsh to Elias, and essentially refuses to acknowledge the more quiet, angsty Lukas altogether. The two get it in their head that she’s somehow been replaced, and take it upon themselves to find out whether this woman, their only caregiver in their secluded house, is truly their mother, and if not, what the hell happened to her.

This is the first feature film from Severin Fiala and Veronika Franz, and it’s a bold statement of style, ambition, and intent. They shot on 35mm, and focus nearly the entirety of the film on the quiet, near-telepathic relationship between the two real-life twins. The scares are sourced from the fears of a child, and we’re put in the pair’s shoes as their distrust for their mother bubbles and eventually reaches a tipping point. There’s some violence, but the real tension comes from the notion that this person they are dependent on and are supposed to love has disappeared and been replaced, and the camera clues us in to the revelations that the script doesn’t. Fiala and Franz know how to keep you interested without busying the frame or cluttering the film with unnecessary dialogue, and the haunting interplay between Elias and Lukas distinguishes this from other entries in the “child horror” genre.

The two writer/directors are 15 or so years removed in age, but it’s obvious that they’re very close, and have formed a unique, successful collaboration. Read on for their thoughts on the genesis of their premise, the trick of extracting these great child performances, and why 35mm is a more viable alternative to digital than many give it credit for:

VINYARD: All I know about you guys biographically is that you worked on a few shorts and a documentary.

SEVERIN: We did a short, but no one knows about it. It’s like a secret short film. A drinking film that only shows us drinking alcohol ’til we don’t remember anything. But we did one documentary before that.

VINYARD: How did you guys meet?

SEVERIN: I was the babysitter of her children, actually, like fifteen years ago. Always wanted to make films, but I was from the countryside and had no possibility to watch films, so I had to go to Vienna where all the big cinemas and video stores were, and that was basically her job. Veronika used to be a film journalist back then, and she would rent VHS videotapes that we would watch together as a kind of payment. We found out that we liked the same stuff, we liked the same kinds of films, which was amazing for me back then that she liked John Carpenter and David Cronenberg films like I did. Out of that grew a friendship, somehow, and we never planned to make a film together at all.

It all like grew, because Veronika got to know this Austrian actor/director who was famous in the ‘70s who was called Peter Kern, who’s very charismatic and always insulting people. Really crazy guy, like 200 kilos big, and gay, and always shouting around, and not able to move properly. He’s crazy. And she said, “Someone should make a film on this guy!” We were asking around to other people we knew, “Don’t you want to make a film on this guy?” And they said no, because they were afraid he was so crazy. So we thought, let’s try and do it ourselves. We borrowed a camera from film school with a friend of mine doing the cinematography, and the three of us did this film (KERN) simply because we though this film should be made. While doing this and while editing it, we had the idea for GOODNIGHT MOMMY, and said, “Okay, let’s write the script for that for fun, as a distraction.” And we did. Then the next step was to say, “Let’s try and direct it together.” It wasn’t a career plan, more like a journey.

VINYARD: How’d you come up with the idea for this story?

VERONIKA: Watching television, actually. We watched this reality show which, here, is called THE SWAN I guess, or TOTAL MAKEOVER or something, where 40, 50-plus women get, as Severin said yesterday, their faces renovated, getting their hair done, their cheekbones or whatever. They’re separated from their families for weeks or months, and after that, they are reunited at a red carpet event. The family will wait on one side and the mother would appear, and of course the husband would put on a smile.

SEVERIN: Fake smile.

VERONIKA: But the children, if you looked at them, they would stare. They could not speak. It would be like, “Oh god, is this my mother?” You could see that they are irritated. There was even one show where a girl says to her father, “This is not my mom.” This was the first idea that triggered the whole story. “What if they had maybe some more reasons to doubt that this woman who came home is actually their mother?”

SEVERIN: We like to play games, so we had this basic idea, then we were sitting next to each other with a laptop trying to surprise each other. “What if that would happen? What if this would happen?” And we’d write it down immediately. It was actually very fast. When we had the first version of the script, we had this method of reading it out loud to each other because that really makes you experience where it’s boring or bad. The other one who was listening was kind of like the first audience, and we completely trust each other when it comes to films, so if the first audience says, “That’s not a film I’d like to see,” or, “It’s boring here,” or, “That dialogue is bad,” we completely trust each other and changed it immediately. It wasn’t this lonely writing process where you’re in your office, all alone, doubting your decisions all the time. It was very fast. The only thing that has to be sure is that you trust one another. If you trust one another, and you know it’s not about vanity or just being right or ego, but about the film, then it’s easy.

VINYARD: You said you were watching a lot of films together. What in particular influenced the script and then the film?

SEVERIN: That’s so hard to say, because you never make a script or a film saying, “I want to put that exactly,” or “That inspiration comes from here or there.” We simply love cinema, and I think all the films we saw were kind of a part of ourselves, so they made us write the script that way, but we may not know why and what influenced us. It’s hard to say. There are some films we love. INVASION OF THE BODY SNATCHERS, the first one. SOCIETY by Brian Yuzna.

VERONIKA: I like SOCIETY by Brian Yuzna. It’s one of my favorites. When we had the script, we rewatched a lot of films about evil children. For example, there’s this Spanish film, WHO CAN KILL A CHILD?

VINYARD: Oh yeah, ‘70s movie.

VERONIKA: Yes. And also THE INNOCENTS by Jack Clayton, I love that very much too. BUNNY LAKE IS MISSING, do you know what by Otto Perminger?

SEVERIN: That’s the most important one. You have to see that.

VERONIKA: It’s such a good ending we didn’t come up with, unfortunately, with our own film. Really great. That’s the way you do it. Unfortunately, we missed some.

SEVERIN: People always ask us, “It’s so similar to that film,” THE OTHER?

VINYARD: The one by Amenabar?

SEVERIN: No, the old one from the ‘70s. Robert Mulligan. They’d say, “It’s the same movie, you made the same twist!”

VERONIKA: We didn’t see it!

SEVERIN: You’ll always miss some films, no matter how good you want to prepare.

VINYARD: (to Veronika) What about your experiences as a mother? Did that play into the script at all?

VERONIKA: Yeah, i think it does, because it’s about some different issues. You have different layers in the film. On one hand, it’s about identity, who you can be in different circumstances, and about masks, about surfaces, what’s behind them, these beautiful faces and the faces behind them. But also, as a mother, it talks about education maybe and how to communicate with your children, and also about, in our days, mothers are working and there’s not this sort of authoritative educational style that there used to be. Sometimes the children have the power, actually, and you feel, as a mother, you’re supposed to be in charge, but you get the feeling that you’re not because you have to work here, you have to do that there, and it’s really hard to educate children. It’s also about these questions to me. Sometimes I really felt kind of tied up because I didn’t know what to do. Children are very powerful, actually.

VINYARD: Another big part of the film is the isolation, in terms of the location. How did you guys settle on the location?

SEVERIN: I think we wanted to strip everything away that would distract from the basic conflict. We were trying to have it as pure and simple as possible to intensify it as much as possible. Of course, if it was in a big city, the children could simply leave the house and go to the next house and say, “My mother’s crazy!”

VERONIKA: It’s over, the film is over! (laughs)

SEVERIN: We tried to keep it up as long as possible and as intense as possible and as pure as possible, so there are no people who are not relevant to this core conflict.

VERONIKA: Actually, the house was more difficult to find than the twins, because it’s a rich man’s house, and rich men don’t need money. They don’t want to rent their house to a film team, so it was hard to find. We wanted the house to be the extension of the mother’s character, because the first part of the film is told from the perspective of the children, so we could not tell you much about the mother, so we tried to use the house and all the closed blinds, the images on the walls, which are out of focus, of a woman you can’t quite get a hold on, so we tried to think of the house as a protagonist.

SEVERIN: It’s so hard if you want to tell this story, then you can’t reveal too much information obviously because then it’s not serious anymore, but you want to know something about this mother and her problems, and that’s what we used the house for. Not just the house, but also this kind of game where the mother has to guess who she is, and she has written on her face that she’s the mother. For us, at the same time, it gets stranger and more mysterious because she doesn’t get it, and at the same time we get information about the real mother. That’s something we came up with to give information and to make it mysterious at the same time.

VINYARD: There’s something I noticed about the film, which is that the twists aren’t really revealed in the script as much as they’re revealed through the aesthetic, through the camera, showing not telling.

SEVERIN: I think the film is telling, but it’s telling through cinematic means. It’s telling by images and by visuals and not by people talking about it.

VERONIKA: When we figured it out, we thought, “How can we tell this not with dialogue, but with images. My ideal would be a silent film, because I think that’s the most cinematic experience, just to tell a story with images.

SEVERIN: The weakness of many films is that they don’t trust the audience, and they speak out everything aloud very clearly in the dialogue, and like three times. They think the people are stupid. We feel that if you concentrate and submit yourselves to this film experience, you get everything.

VINYARD: A big part of communicating that subtext is the actors, and in this case you have two young actors. You said they were not that hard to find. How did you find these kids that you had to trust your whole movie with?

VERONIKA: The first step is you call schools and ask principals if they have twins in the school. Then you gather about 125 pairs of twins in an audition room, which is kind of scary. We experienced that, with most of the twins, one was the better actor than the other, so the task was to find two equally talented children. In the end, we had three pairs of children we all liked, and we had this last audition round where we tied an actress to a chair and told the kids, “This woman is not your mom. You can do whatever you want. You have to find out where your mom is.” Two pairs of them circled around and shouted at her, “Where’s our mom?! Where’s our mom?!” The final pair grabbed a pencil and pinched her in her arm, so we thought, “Okay, that’s a courageous thing to do.” (laughs)

SEVERIN: We’re not so much into dialogue.

VERONIKA: So we like pinching people! (laughs) To overcome that border of, “This is an adult, this is an actress, and I’m an 11-year-old,” that’s a courageous thing to do. They were the best ones. But then you need luck, because you don’t know if they’re resilient enough, because they’re children. You don’t know whether after two weeks they’ll be like, “This is boring.”

SEVERIN: Let’s go home.

VERONIKA: We had to figure out a method how to do it. We shot it in sequence, we didn’t give them the full story.

SEVERIN: Every day, we gave them a little more information to keep them interested.

VERONIKA: So they tried to find out. They tried to ask the whole crew.

SEVERIN: And of course, it’s luck, as you put it, but at the same time you have to work for the luck. We have this hail scene in the film, which was kind of luck that it hailed, but at the same time, you have to be open to accept those gifts and presents you get. Because when it hailed, most film crews would probably say, “We have to shoot this scene inside because it hailed and we can’t shoot.” We’re like, “It’s fantastic! Let’s run out and get the hail!” You have to be open for that. You have to be open to accept luck and the presents you get.

VINYARD: One thing I love about the kids’ performances is how comfortable they are with each other. They’re very violent towards each other, there are scenes of them fighting, and running around fire towards the end. In the U.S., it’s very hard to get permission to use child actors for stuff like this.

VERONIKA: Really?

VINYARD: Yeah. Very long turnarounds, they have guardians constantly on set, things like that.

VERONIKA: Okay. Yeah, it’s easier in Europe, maybe it’s easier in Austria. There are laws, of course, of working hours with children. They had their parents not on set, but at the hotel, so when they came home, they were there. There was a psychiatrist, and if she had the feeling that something was wrong with the children, she would’ve interfered. But they said it was the best summer of their lives, so…speaking of violence, it’s totally different how you see it in the film than how we shot it. The most challenging scene for the boys was this long fight in the bathroom because they didn’t like to do that actually.

SEVERIN: You see the way it’s filmed, you see they really have to fight with each other, but like the stuff later in the film, it’s all technical and doesn’t involve any violence at all.

VERONIKA: We gave them, “That’s maybe not your mom, and you need to find out.” That was one point, to protect them, the idea that it’s not their mom. The other was that they’re fighting for something, they’re trying to get their mom back. That’s the most powerful thing you can have, maybe.

VINYARD: And the mom is so crucial. She’s the only adult character in the movie. How did you settle on Susanne Wuest for the role?

SEVERIN: We knew her before, and we always knew her face had to be in some kind of scary or horror films. Halfway through the screenplay, we got the idea that she could play it. Then, we wrote it with her in mind.

VINYARD: You shot on 35mm. Why the decision to shoot in 35?

SEVERIN: Because we love it. We tested very many formats of shooting, and we thought it’s the best and most beautiful, the one that had the most secret to it. It’s like alive, it feels somewhat alive. All the technicians that were sitting with us in the cinema watching the screen test said, “Are you sure? That looks out of focus, it’s not as clear.” Yeah, but we like it. It’s alive, and we love it. That’s the main reason for doing it. The second important reason is that if you shoot on a digital camera, and we were advised to do so because we’re first-time directors and we’re working with children and animals and whatever, they say, “You can just press the button on a digital camera and let it roll forever and something good’s gonna come up after maybe 10, 15 minutes.” We thought, “Maybe that’s right, but everyone else falls asleep!” Even the cinematographer falls asleep, because he’s watching it for 20 minutes. We felt like shooting it in 35 would be a completely different kind of concentration and focus on the set, because you press the button and it’s like holy. In the next 20 seconds, the good stuff is gonna come up, and everyone knows.

VERONIKA: It’s a completely different energy. It’s very interesting to talk to cinematographers about the changes that come up now that they mainly work on digitally-shot films. They always tell you, “We can do this in post-production. You can do everything in post-production!”

SEVERIN: You have to do it all in post-production.

VERONIKA: And that makes it different, what you want to achieve on the set, what you want to try and get out of the actors and the situation.

SEVERIN: I don’t think it’s cheaper shooting digital, because in post-production you need a lot more time and more work. I think it costs the same. We decided on 35 because we like to decide everything on the set. We wanted to decide the look of the film on the set, and not later on with some technicians in a lab.

VINYARD: How did you choose your cinematographer (RAVANCHE lenser Martin Gschlacht)?

SEVERIN: He was recommended to us by our producer, Ulrich Seidl, who said, “You can make the decision yourself, but the cinematographer is very important and I want him to have worked, and this will be a good one.” He’s very professional, and very experienced, so we had a bad feeling that he wouldn’t be interested in working with us and working on this story, because it’s our first film and he did three films that year already. We felt kind of uncomfortable, and we were proved completely wrong. He is like the most curious and dedicated person. He really wanted to find out how we want to make the film. It wasn’t like, “I’ll do it the same way I do every film,” he was very interested. He was also fighting for the film when it came to working with other people. Normally, many technicians aren’t too interested, and if they think you do it differently, then they deem is as unprofessional and they roll their eyes and look bored. This would’ve never happened with our cinematographer. He would go up and say, “They’ve spent so much time thinking about how they want to do it and the script, and you’re just here for one day, so stop rolling your eyes!” He was always fighting for the film, the story, and for us. Really great experience.

VINYARD: How did you hook up with Ulrich?

VERONIKA: I got to know Ulrich 20 years ago. I am his collaborator. I’ve co-wrote all his films for 18 years, since DOG DAYS. We also have two children.

SEVERIN: They live together.

VERONIKA: He had nothing to do with the script, we wrote it by ourselves. Then we gave it to him, because he also has a Dutch company. He said he liked the script. He was a very generous producer because he’s interested in money, but he knows that it’s more important that you have the freedom to do what you envisioned or what you think is right for the film, so he always puts the artistic vision first before the money.