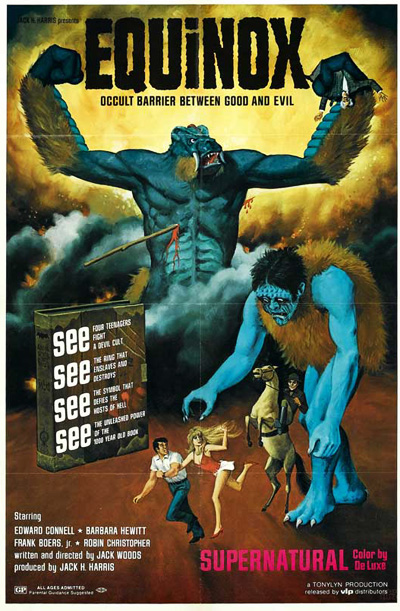

Hello ladies and gentlemen, your pal Muldoon here with a truly exciting read, a tiny peek into the mind of one of my personal cinematic heroes. You've seen his work in countless films, blockbusters that have pushed the medium forward in terms of spectacle, and no doubt have been moved by his work. The man's won nine Oscars and carved some of the most memorable shots out of some of our favorite directors' imaginations, bringing things to life that a given director simply couldn't do on their own. With MEET THE CREW, I really do hope to provide perspectives that aren't director/actor centric and again, that's absolutely not devaluing their hard work, but shining some light on all of the wonderfully challenging jobs behind the scenes that you might not know about, individuals who don't typically do the rounds come press time, folks who bring a given director's vision to life. Personally speaking, I'm not sure I'll ever be able to top this interview; it's brief, but we cover all sorts of topics, and topics I'm a big fan of - like the "go out and make your movie, not excuses" approach that he and his friends set out to do with EQUINOX. The man's accomplished so much, it would be so incredibly easy to chat with him about any given project for hours on end. I mean the man brought dinosaurs to life, gave us our favorite STAR WARS ships flying through space, gave life to the T-1000... The list goes on and while I certainly wish I could have picked his brain for hours and hours, I more than appreciate the time he was able to give me here. Opportunities like this one are the sole reason why I write for AICN, to dig into that intangible concept of "what makes a good movie great?" Hopefully you folks enjoy the chat as much as I did as there are some real genuine nuggets of great advice sprinkled throughout the interview. Thanks again to Mr. Muren for his time, modesty, and for sharing a few stories I'd never heard before.

DENNIS MUREN - VISUAL EFFECTS SUPERVISOR

Before we get started, I did want to thank you for taking the time today out of your busy schedule to chat with me. I’m a big, big fan of your work. So let’s just jump on in. Can you tell me a little bit about your relationship with Rick Baker? I had read that you had known each other growing up?

It was erroneously reported somewhere along the line, but yeah I’ve known Rick maybe since I was about twenty or so, which is not really childhood. I’ve known other guys much longer than him, that was in response to somebody asking me years ago “did I know anybody who had become really successful that I had known when I was younger.” I mentioned Rick, but really I was about twenty when I first met him, which at that time he was probably about fifteen or so and just doing amazing work. He was a young guy.

You two are obviously both legends in your own fields, so there was that “is this true?” question that popped up when I saw that.

Yeah, I was friends with this group in LA, and you probably know some of the names, Jim Danforth and Dave Allen, that both did EQUINOX. All those guys did and we were a pretty tight little group and then just kind of expanded and Rick was one of the guys that kind of came into it, but he was doing makeup and not so much doing stuff we were really into. It was actually that there were so few people in Los Angeles that were doing any of this stuff, not like what you would expect, because there was no industry really for effects back in those days in the sixties. So we sort of found each other, all of us younger people, and we called the old guys… We found them in the phone book like Howard Lydecker and stuff like that… Even Ray Harryhausen was in the phone book. You’d call them up and most of them were just thrilled talking.

I can’t even wrap my head around that, that it was that easy to call up these titans and they’d give you the time of day.

Yeah, yeah that’s right as so few people were interested in it that these guys were never bothered by a lot of people calling them. They were mostly just surprised that anybody was even interested and cared about them.

I guess times have changed, at least from where I’m sitting. You mentioned EQUINOX. It feels like that’s a film where you set out to prove something to yourself and I don’t want to put words in your mouth. Where did EQUINOX come from and how did you get it going?

Yeah, the whole deal was it was my project in the beginning. I had been making short films since I was… probably since it was with still photos, so I was about six or seven years old with special effects stuff. I had been making little movies since I was about ten and you know, you make these little movies with friends and stuff packed with effects and show them to people. After doing that for seven or eight years, you’d just sort of get tired of it, because nobody else could see it. So I had a summer coming up, a vacation, while I was in college. It was the summer after my freshmen year and before my sophomore year and I started thinking around that Christmas time before the vacation, “Can we just make a movie?” I mean I just figured I’d made a lot of shorts and “what’s the difference between making a short and making a feature?” I had this love for the Harryhuasen films, THE THIEF OF BAGDAD, and things like that. They’re all really episodic, right? They’re all like little films within themselves going from this event to that event, a spectacle. So I thought “a feature film is nothing but little episodes and heck, we could do that if I could just get some people who wanted to work on it.” So my grandfather had put away $3,500 for college for me to go to a school like USC or something like that. Well I never had the grades, so I just went to the local Pasadena Community College and I asked him if I could have that money to make the film and he said, “Okay, good luck.” So I budgeted out how much money it would cost with 16 mm to shoot the movie, how much to buy the film, to have it processed, to have it printed, to somehow put the sound on it. I think we were going to shoot it silent and add he sound later on and all it came out to was like $2,800 and so there we go, we could do it.

So I started calling around and I talked to Mark McGee, who was a friend a couple of years younger than I was and who is a writer… He was seventeen. I was eighteen and so he wasn’t really “a writer,” like I wasn’t “really a director” or “a producer” or anything else… Except he agreed to write the script for it and I think this is probably like January or February and my idea was shooting in like June, since we all got out in June and we would shoot for two weeks. I figured we could definitely get the thing done in two weeks while looking at LITTLE SHOP OF HORRORS that took something like three days… We heard stories like that and thought “We can make this thing in no time” and I just used my Bolex camera to shoot it with. I just got 100 ft rolls of film…

So Mark wrote the script, David Allen agreed to do some visual effects for it. In the script, Mark had this flying demon and Dave said, “Yeah, I’ll make this flying demon creature.” I moved to do a forced perspective sequence, so I had Mark add in this thing where a green giant walks around. There were a lot of other forced perspective things in it… So Mark came up with the story and my friend Jim Danforth came on board and we found the actors, which was a big deal. The girl in the film came right from my high school, Barbara [Hewitt] and the other one came from Arcadia High school where Mark went to school and the two guys we found in an ad that we put out in The Hollywood Reporter and neither of them had really acted that much before, but they all agreed to do it. We started shooting and we found some nice locations right outside of LA and after about a week of shooting, or a week and a half, we realized two things: One is the script that Mark had written would have only made about a thirty minute movie. He had no way of judging that and we shot most of it, but we just didn’t have enough for the film, so we were kind of like “Hey a movie’s got to be an hour or an hour and a half, something like that…” So that was kind of the end of it. We just stopped and said, “What the heck are we going to do?” That’s why the movie took two years to make, because Mark kept working and then we went back to school, so (Laughs) we were distracted by that and we just wrote sequences that we could put in the thing, like five or seven minutes of a movie. We’d go off on a weekend and shoot that seven minutes. We just kept doing that for the next year and then we got it to seventy-one minutes or so and then when that was done… And during this whole time we are all doing the effects. I was doing the effects with Dave Allen on our own also. So that’s kind of it. We got the thing done. I could afford to make three prints, three 16 mm prints, and I found a local guy in Pasadena who had a sound studio and we raised $2,000 from some investors who threw money in to do the sound and he was a great guy. So he did the sound for it and I entered it myself, just literally physically cutting it with the film in a little backhouse we had. There was no camera to look at, it was literally just cut ins. I’d run it through the projector and look at it, that’s how I would judge it. Then it was done and we showed it. I think it was seventy-one minutes and I think that’s the version that’s on the Criterion disk, our version of it. After about a year or so somebody said, “You need to show this to Jack Harris.” The man had done DINOSAURUS! and THE BLOB and stuff like that, but he also bought… which I didn’t know anything about, these foreign films and he would dub them and change the editing and release them. This guy I knew, Tim Baar, who worked on DINOSAURUS! said, “you should talk to Jack” and I ended up selling the movie to Jack.

He wanted to shoot more stuff and make it longer, more professional. I was just tired of it. I didn’t want to keep at it and nobody else did, so he just did this whole other version on his own. He used a lot of our footage, but then also a lot of other footage. That’s the version that got released and it’s pretty amazing actually, because he never ever… It got a “major release” you could say, but I thought it was going to be very simple to sell it when we were done. I thought we could sell it to the TV stations, because there were a lot of movies on TV that were pretty darn bad and this had visual effects in it that weren’t great, but weren’t the worst. I couldn’t’ find any of the channels around LA that would buy the film at all. What I found out years later is what they do is they buy packages from studios, like twenty or forty films and they will get two good ones and about thirty bad ones, but they weren’t about buying a singular film, so that’s why I ended up selling it to Jack. I tried all different ways to get the film a release, essentially talking to anybody that was interested in doing it, and Jack was clever enough to see that it there was something in there and he could make it look professional.

It clearly got out there and it’s packed with all sorts of fun effects. I remember that giant you mentioned and the fact that you guys were essentially kids and still had your day jobs, going to school, and doing other effects. That’s something I guess most folks don’t do… stop talking about making something and just finding a way. I can’t imagine there were too many eighteen year olds doing that at the time or even now.

That’s how Criterion felt about it also. L had never seen it that way until somebody brought it up, recognizing it as a “do it yourself” film. I knew some people who tried it and they have never finished their films, other people have and they’ve gotten them out. Ours was just a way, way over reach as far as the money and script. Even though we were about an half an hour from Hollywood, we really didn’t know anything about how movies were made. We had no clue… no clue about how long the script needed to be… Oh, and I shot the thing also and did a bit of directing and Mark directed… We thought these things were made without the editing. We thought they were edited when you shot it, so we didn’t do any coverage. We would just shoot for cut per cut and so when you see a close up of an actor saying something, that forty frames was all we shot. When you see a shot of the whole group talking and they talked for like twelve seconds, that was all we shot, the twelve seconds. So the actors had no ability, no time to get into character, because we didn’t think that’s the way films were made.

Well you did save money on film stock, though… So that’s not too terrible.

(Laughs) Absolutely.

I saw your name was attached to the original WILLY WONKA and FLESH GORDON and I’ll be honest, those movies don’t feel like films I’d associate you with. Nine Oscars… countless blockbusters… What did you do on WILLY WONKA and FLESH GORDON? I’m more curious about the stuff that people don’t really talk about on “behind the scenes” bonus features… What were some of your duties on those earlier films of yours?

Well with WILLY WONKA I was working for Jim Danforth and he did these two shots of the wonkavator flying and he was working at a company called Project Unlimited. I was friends with Jim. I was seven years younger or so, but I did the motion tracking and projected the background plate onto the rear screen and I sort of plotted the camera movements the helicopter had made, so that he could try and correct the animation frame by frame of the wonkavator in front of that background, because he didn’t have any way to stabilize the background image. There was really no way in those days to do that.

So that’s what I did on that show, but it was just a couple of weekends and we had to do them on the weekend, because they were a normal business that was busy with so many other shows during the week. I was still in high school when that was going on and then on FLESH GORDON some friends of mine got the job and I came to do some of the modeling work on that and I was on that for a long time shooting miniatures just flying through the air. I was just working with a bunch of friends and by that time all of us younger people in LA, the total of like ten of us or whatever that were doing effects, that was a show we all came together on and got a lot of work. The chance to work for two months and make some money… And the show just really grooved. It was originally a soft core porn movie, but my friend Mike Minor got the job on it helping with the Art Direction and they saw how wonderful the movie was looking and decided to try and turn it into a regular film, maybe an R rated film or something like that and they put more money into it. They wanted to add more and more effects to it, and there weren’t that many chances to get to work with 35 mm, which all the effects and everything were shot in 35 mm.

I can assume back then especially that that was a giant step up, a different playground to play around in. That’s not cheap stuff.

It definitely was a step up. (Laughs) There were no steps “down.” There was no place where we could go, because we were already as low as could be! There were no jobs, no ways to get into the industry. You had to be a union person, but you couldn’t get into the union very well, and there just weren’t many movies with effects. They made about one or two a year at the most, like THE TOWERING INFERNO or EARTHQUAKE, something like that and here those were big studio movies and nobody really wanted us to work on those. So we were just out of work.

Speaking of “big studio movies,” I don’t even want to try to list off all of yours… I can’t believe I didn’t lead with this one, but what exactly is it you do? If you had to describe what you do to a person who is completely unfamiliar with visual effects, how would you do it? What are some of your duties that aren’t necessarily romantic, not “having lunch with Steven Spielberg while pitching him some cool idea…” What are some duties that are real world, tasks that don’t pop up when one first thinks about visual effects?

(Laughs) Well I don’t really pitch ideas unless we’re on set, but what the job title involves is the directors have got to have somebody that shares their vision or sees what their vision is, so they can talk to one person that’s going to get that vision done. That’s what I… With everything I’ve done, if you look at… If you look at our old movies, like EQUINOX or the other films I did before STAR WARS, I always had an idea in my mind what the finished scene should look like. George Lucas would always say “You’re a filmmaker” and I truly was, but not from the director’s side, more from the effects side. I sort of saw the finished scene in my head and I could assemble the stuff needed to get that scene and then I would shoot them myself. Other people for example will be specialists. There will be a person who just loves to do matte paintings and make models or be an effects camera man and they get hired to set up the cameras, but I always had another view of it, so when I work with Steven or George or someone like that and they are talking about an idea for this one shot, like in STAR WARS, I immediately had in my head a vision of what that whole shot would look like and in my mind seeing the right angles to shoot it from, the speed it should go, George or Steven’s intent with it was, and then I would assemble the people to make it that, because I certainly couldn’t do it myself as there were too many departments and I’m not good at like model making or much of anything except photography. So I worked on the storyboards with the Art Director and go shoot it and say “Yeah, that’s right.” That’s kind of what it is and the good thing for me is my vision, what I saw in my head was sort of the same as George and Steven and Jim Cameron’s. If you don’t have a shared vision as those guys, then you’re sort of screwed and they are kind of screwed also. But since we are all sort of the same age and all grew up with the same films… Steven said one time on the set of a show “I want this to look like the creature from THE MAN FROM PLANET X” and I guarantee the other two hundred people on the set had no idea what he was talking about and I knew exactly what he was talking about. I don’t know if you’ve seen the movie, but the face is static and it’s only in a few shots of the film, but I knew what his idea was where other people had no idea.

So it’s called “Effects Supervising,” but what I’m doing is more like “Effects Directing” and I represent the vision of the director and make sure they get what they need.

It sounds like you speak the language of some of the greatest storytellers in the past century. Looking back, where there many people who early on “gave you a shot?” I know you had worked with multiple friends essentially building magic out of nothing, but was there ever a specific moment when someone gave you a job because they believed in you before you were “Dennis Muren?”

Yeah, you know Cascade California Effects Department doing television commercials. That’s where Jim Danforth was working and he gave me a job there and I was sort of on and off for years, so it wasn’t until about two years later that I became a permanent employee there, but I didn’t really have… One of my critical thinking skills came from Jim Danforth as I was really close with Jim and he was very open and taught me all sorts of things, one of the main things being about critical thinking or how to see things fro ma different point of view and begin able to look at your work critically and not just being thrilled by it, but also “I can solve this.” That’s usually really hard to learn for somebody or to learn at all. Those guys were sort of the ones to really believe in me when I was young, but I’ve got to say I kind of had nobody. When I went out for STAR WARS I had to interview for that job and had just found out coincidentally that it was being done. I didn’t know any of the people that were doing the effects on it, but I had met John Dykstra once before and ended up claling him up for something to see if there was any work and showed him some stop motion work I had been doing at Cascade, just whatever I sort of had, and ended up getting hired on that show. But that was because I had a reel of stuff that I had been doing for years and also I was eager to learn all about the motion control stuff. He saw my stop motion background might be useful and had me programming these spaceships moving around. So that’s what he saw in me and it was great, I just picked it up.

It sounds like maybe you already had it instilled in you, but an attention to detail and an eagerness to learn something new. Those two things I’ve always found to be massive when looking at successful people, in anything, not just film. You know I’ve seen a few interviews of yours where people ask you “what’s the future of visual effects? Where’s to headed?” So your thoughts on that are out there, but how about “What’s stayed true throughout the years?” What are some obvious lessons that maybe you learned along the way in your wild career that always seem to hold true? Does that even make sense?

(Laughs) It makes sense to me, but then I look at some of the work on screen and think “That doesn’t look very good…” and I start to think “Well there are no lessons,” but it has to do really with it being art and principles of gravity and design, of course creativity. To me, the technology is something I’ve never actually been interested in and I’ve pursued it, but it’s always been with the intention of creating something I couldn’t make with the technology at hand. So those are the principles that I think are the most interesting, which are the aesthetics. So I can look at some of the aesthetics like what John Fulton did in THE INVISIBLE MAN RETURNS and definitely apply the same ideas he used in something that I’m doing today, absolutely directly, except the tools are completely different and it’s probably a lot easier for me to do it. But there’s some really clever stuff done… like Harryhuasen who had more to do with aesthetics and stuff like that, like how the shot unfolds and how the shot is designed, being daring on something. Setting up the shot and shooting the shot really takes place only after the really important work has been done when you’ve designed everything in your head and you know from the director that he trusts you enough to change things around or add things to it. I don’t think any of that has changed. I think you could put a talented filmmaker in any era and their work would be super good. It’s not the tools. It appears to be the tools, because you could look at the tool set and sort of focus on it and say, “The computers did this.” Yes, well the computers did make them look more real, but in the hands of someone who doesn’t understand how to tell the story or what reality looks like, it just looks fake and stupid.

Ultimately the shot itself can be as pretty and wild and crazy with explosions and all sorts of fun stuff comped in there, but if the story’s not good, then that magic isn’t there and the audience is almost robbed of truly feeling engrossed in the effects at play.

Oh yeah and the story can be a four second shot, it’s all about how it reveals itself. The shots I like the most are called “evolving shots,” because it may only last three or ten seconds, but they move from one idea to another within one shot. I just like those the most.

I really don’t want to eat up much more of your time, but I write as “Muldoon” on the site, an obvious JURASSIC PARK reference… That’s “my STAR WARS…” and I know I’m not alone there, but still that’s the movie that got me working in film myself and writing here on the site, so with JURASSIC WORLD… That’s a movie I honestly never thought I’d get to see and I’m so glad I did. I’m so glad everything came together.

Yeah, I had no clue if it was actually ever going to get done.

No doubt there were many iterations one what it could have been, with scripts whipped up by some of the best writers out there, and then it seemed to get pushed right before it was to start production… The dinosaurs in that film… You guys went all out on the CG and some people might say that almost dismissively, but I was honestly blown away with the liveliness of the creatures. They all felt real, like when they moved their head, their fat jiggled. There are those details that sold the whole thing. I’ll probably be burned at the stake for saying, it but other than the animatronic Apatosaurus, I don’t think I missed the puppets as much as I thought I would. Clearly it’s whatever looks best and help provide the actors with something to play off of, but I wasn’t expecting as much CG oddly enough. What did you bring to that show? I know that’s a giant question, but what are you most proud of when you watch the film?

I sort of thought that we really hadn’t topped the first JURASSIC PARK very much. There are a few things in the second one and the third, or that anybody else has really done even, but that original film just really nailed it and when I was doing that I thought that it was over. “This movie will be obsolete in five years,” because I knew it was missing the muscles moving under the skin and the sense of weight and reverberation through the body. I mean you could see it in real animals when they are moving, but we just couldn’t get it with any technology that we had at that time and we had been talking at ILM for years about what to do to make that look better and then this show came up and the guys just bought into it and everyone did a great job from the director up. We wanted to top that film and we had a lot of meetings about it and I while I was really encouraging, I didn’t really contribute artistically much. I did really help encourage them to do the motion capture for the dinosaurs, because I thought that it was too hard to animate those really with any sort of computer animation or key framing or whatever kind of animation and so Glen McIntosh worked really hard on getting mocap with it, but all the guys we had playing the animals, but a lot of it ended up being key framed, but they had that original mocap stuff to look at, which had the weight in it, you know? So I didn’t contribute much and I don’t want to say that I did, but I was really glad that everybody wanted to really come up with something different. I helped Tim Alexander a little bit with the lighting and a few things he was having trouble with that you lose sight of when you’re working on it. It helped the director just loved the first movie also. He’s terrific and he’s going to be doing the final STAR WARS film too.

Colin Trevorrow. Who would have seen that? It’s exciting. I guess Frank Marshall and everybody there really saw something in him with SAFETY NOT GUARANTEED and his shorts… Now the rest of the world has as well.

Yeah, the guy’s terrific.

I’d love to talk with him some day, but we will see. (Laughs) It’s no small feat that with the first JURASSIC that you brought life to these digital assets and gave us all something special with seeing living dinosaurs in such a wild story of a film. To wrap this up a little bit and gear it back towards my MEET THE CREW style questions, when are you typically brought on to a given project? It feels like it could be last minute or something where you’ve had many years in prep for. What’s the average that you’ve come to find?

You mean how do I normally do a show? I’m mostly half-retired now. I’m only at ILM two days a week and I’m not doing shows, I’m looking at the work and commenting on stuff and talking with the producers and stuff like that. I’m not some sort of guru master who is directing everybody through magic or anything, but I’m there just to sort of pass on stuff. So occasionally, like in SUPER 8 I’m brought in to find stuff at the end and I got pulled into that… I don’t know how that came about, but the stuff before that is pretty much the stuff where they’ve asked for me to be on and if it’s something I want to do, then I’ll jump on it. I always like to work with directors that are really good. The directors lead everything.

That makes total sense and speaking of good directors, you’ve literally worked with some of the biggest blockbuster-building directors out there. I assume they all have a few similar traits. What’s are a few key traits you see in the greats as opposed to the “bad ones?”

Well the directors that I like are the ones the ones that know what they want and they’re not always the most fun movies to work on. The most fun movies are when the director says, “Hey, do whatever you want here, just design a sequence and do it.” That does happen and a lot of films happen that way where you just… Look, I don’t do this very much, but you work on creating an entire sequence and the director looks it over and maybe gives you storyboards… I find that those movies are not as good, because the director is not seeing the effects as if they are an animal or something, a character, and they should be. So all of the guys that I think, the top effects guys like the Camerons, the Spielbergs, the Lucas’s… those guys understand effects very well and know pretty much what they want. They are all open to ideas and changes, but they know the intent of what they are trying to do and they have the designs worked out with the emotions they are trying to create. Those are the best guys to work with in my opinion and they’re not the easiest to work with, but the film will be better in the end and that’s all I care about, the end result and not the process. Another thing that can happen is you can have somebody with a really strong personality and knows exactly what he wants and it be something the audience just doesn’t care about. That could have been STAR WARS. For whatever reason, if it were five years earlier and the baby boomers weren’t ready to see it and it just came out and went away like 2001, and didn’t make a splash or leave you anything… that’s the other side of what can happen. I was just really lucky that the audience was ready to see STAR WARS and everything that’s happened since in the last forty years.

Clearly STAR WARS is an insane empire now with more merchandising that I can even wrap my head around. I assume every day of your life you are asked questions about STAR WARS, so I’m not going to go there now although I’d like to. I know we’re already ten minutes over what we expected for this interview, but I do have a silly question… Where do you keep all of your Oscars?

They’re all over the place. I’ve got friends here that have them, relatives, and stuff like that. They’re just all around. They migrate around.

That’s fair. Well, Mr. Muren, thank you genuinely for talking with me. I’m a little bit beside myself as a massive, massive fan of yours. I’d love to talk your ears off about each and every film you’ve been a part of and in great detail, but I know you just don’t have time for that, no one would, but I did want to thank you sincerely for taking the time today to chat with me.

Yeah, well sure. I’ve followed the website since it was first created.

Well, have a great evening.

You too. Maybe we will meet up some time for something.

(Laughs) I would more than love that. Have a nice night, Mr. Muren.

All right, bye.

There we go, ladies and gents - a little insight into Mr. Muren's world, that of a legendary Visual Effects Supervisor. I can't express enough how cool it was of him to lend an ear for MEET THE CREW. One thing that's different with MEET THE CREW, just something to remember, is it's not part of any press tours - it's not an opportunity that pops up via a PR agency hired to promote a film, instead it's real people talking about what they are passionate about. To me, those are the only folks I want to talk to, people who do what they do because they love it. I hope you enjoyed the read above, and remember there are more MEET THE CREW articles with all sorts of positions below, so if you see a name/position you'd want to know more about, click the link below:

If you work in film or television and feel like shedding some light on what exactly your position entails, then please feel free to shoot me an email with the subject line "MTC - (Your Name) - (Your Position)." I'm not here to get scoops or dirt on anyone, simply here to educate and ask for advice to any of our filmmakers in the audience.

If you folks are interested in finding out what other positions on a film are like, then check out any of the links below:

Robby Baumgartner - Director of Photography

Thomas S. Hammock - Production Designer

Seamus Tierney - Cinematographer

Brian McQuery - 1st Assistant Director

Shannon Shea - Creature/VFX Supervisor

Christopher A. Nelson - Special Makeup Effects Artist

William Greenfield - Unit Production Manager

Jeff Errico - Storyboard Artist

Monique Champagne - Set Decorator

Arthur Tarnowski - Film Editor

Justin Lubin - Stills Photographer

Jason Bonnell - Location Manager

- Mike McCutchen

"Muldoon"

Mike@aintitcool.com

![]()