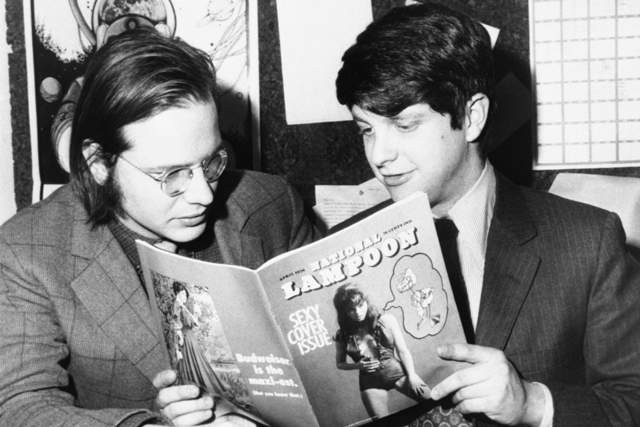

For most folks under 30, when you think of National Lampoon, you probably think of the movies. Maybe you go back to the days of ANIMAL HOUSE and NATIONAL LAMPOON’S VACATION, or maybe you recall the scores of NATIONAL LAMPOON cheap-o comedies that used to line the shelves at Blockbuster. Even though you know what the National Lampoon brand signifies, namely humor of a sexual, scatalogical, or generally irresponsible nature, it’s less likely you know where the brand originated: the National Lampoon magazine.

Doug Tirola’s film takes a look at that original run, spearheaded by Doug Kenney, Henry Beard, and Robert Hoffman, and tells the story of how the Lampoon empire expanded into radio, stage performances, and eventually cinema before being bought out and co-opted by, shall we say, less creatively-inclined entities. As Tirola mentions, this is no rote, talking-heads retrospective; to the director’s credit, he leans heavily on the mounds of glorious archival footage, audio clips, and magazine covers to convey just how funny, radical, and striking the Lampoon humor was, even to our modern eyes/ears. One of the most shocking aspects of the doc is just how far they were able to take their magazine and radio show into raunchy, often heavily sexual/political territory without having their hands bit off for reaching into the cookie jar, and the vast majority of the humor plays just as well now as I’m sure it did 40-plus years ago.

Plus, Tirola knew that with the talent involved with Lampoon you could let their comedy do the talking for you: we’re talking folks like Michael O’Dononohugh, John Hughes, John Belushi, Mike Reiss, Tony Hendra, Gilda Radner, P.J. O’Rourke, Chevy Chase, Harold Ramis, Al Jean, and both Bill and Brian-Doyle Murray. Even just getting a surface view of these various talents and what they contributed to the Lampoon pantheon conveys the genesis of the type of comedy that defined the late-’70s and early-‘80s and still influences TV and film to this day.

Tirola was unusually kind and generous (even letting me cut into his lunch time) as he discussed his personal history with Lampoon, getting (or failing to get) all these talents in front of the camera, and the tough times the brand has gone through over the past 25-or-so years:

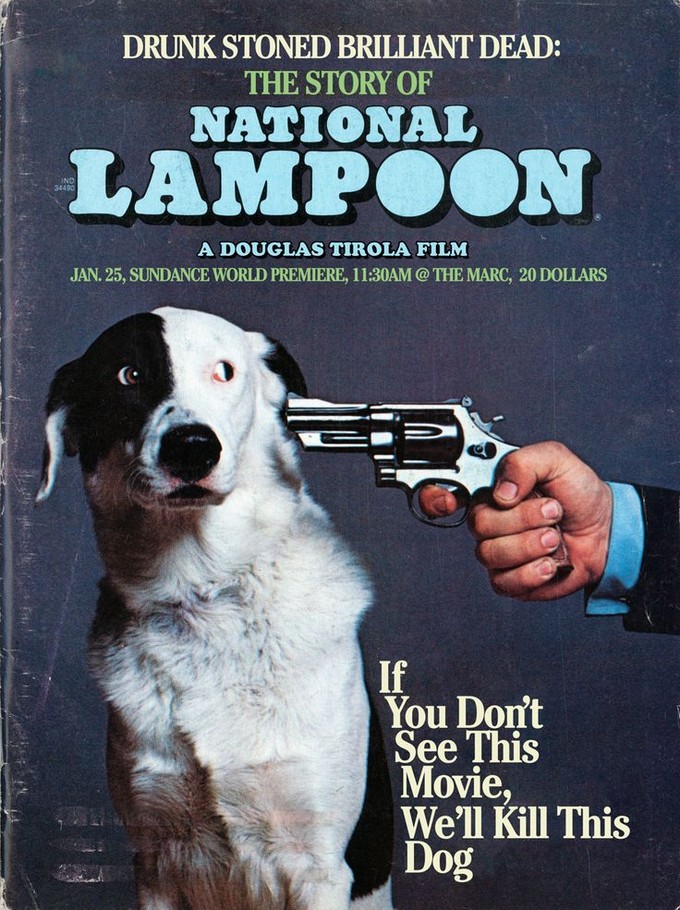

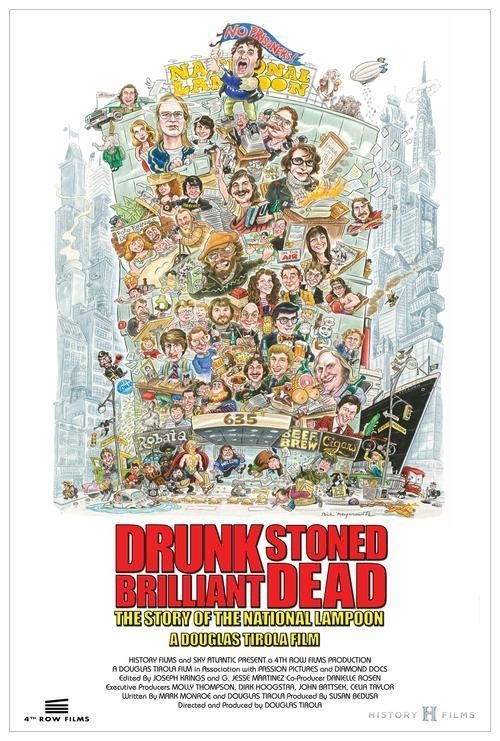

VINYARD: Let’s talk about the poster for a second.

TIROLA: Do you like it?

VINYARD: Yeah. “Rick Meyerowitz,” the guy who did the ANIMAL HOUSE poster, right?

TIROLA: You’re the only person that knew that. Rick Meyerowitz did the ANIMAL HOUSE poster. I actually own the ANIMAL HOUSE poster from when I was a kid. I love that poster. I went to ANIMAL house because of that poster. What had happened was, even before we started making the movie, I said to Susan (Bedusa, producer), “We’re gonna have to somehow convince Rick Meyerwitz to do the poster, and obviously it needs to look like the ANIMAL HOUSE poster.” So we got to know Rick, and he was great. He didn’t want to do a poster. I think he’d only done one other movie poster. Then he finally said he would, and he brought us a couple of sketches, and it was like this dog with the gun to its own head.

It was just…you know…”ANIMAL HOUSE had 48 characters, and this has to be that. Couldn’t it be more…” So after like six months of really going, “Come on,” he did it. He took a long time. The reason it’s shaded is there’s a second ANIMAL HOUSE poster when the studio re-released it where he uses that effect, so he wanted a shaded New York in it. He put the ANIMAL HOUSE on top of the New York City buildting. What I think is great about it is it has that ANIMAL HOUSE feel to all these different characters, so it’s like half people that worked there and half stuff they created. It really represents the look of the Lampoon, the magazine. One of the things that’s great about the Lampoon is that it’s sort of like a great movie in the sense that when you stop a frame of a great movie, you can tell that there was a 2-hour meeting about the ceiling panels, you know what I mean? “Did they have panels in this bar in 1930?” When you watch a great movie, everything is thought about. When you look at the Lampoon, every piece of that magazine- like if they do a parody of New York Times, there’s a joke in the numbers. It’s a little bit different than The Onion like that, where everything’s a little bit bigger. There’s not that level of detail.

I mean, look at this poster. It’s got everything! Here’s John Landis, who made KENTUCKY FRIED MOVIE, and here’s Kentucky Fried Chicken. I love this poster. What’s different about this poster today is, in a digital world where people are looking at everything in a smaller image than the smaller movie poster, you tend to have movie poster art that’s more a singular image because it reads easier. Magnolia’s great, they did two other posters. One has Mona the Gorilla, one has the dog. But the fact that they let us have this one as well, which, in the lobby at least, I think is great.

VINYARD: You mentioned that you saw ANIMAL HOUSE when you were a kid. What was your first exposure to the magazine?

TIROLA: My first exposure to the magazine…I have these memories of being at friends’ houses where they had older brothers, and it’s kinda just casually out. I think, in retrospect, they were probably thinking like, “This is as close as I’m gonna get to a Playboy living with my parents.” Even though I hope they looked at it more than for that reason. I think that some of those older brothers seemed like really smart, like the Holden Caulfield type kids, and I thought in retrospect like, “Wow, they were really intellectual for their age.”

For me, after ANIMAL HOUSE, there’s this 10th anniversary anthology that was done, this big hardcover book. The editors went on the Today Show to promote it, crazy to think about. That had a collection of everything from the Vietnamese baby book, Doug Kenney’s “My Favorite Blowjob,” all these different things, many of which, not by design, ended up in the movie. Not because I’m a slow-reader, but I’ve had that book with me since I bought it as a kid. Took it to college. You know how some items go with you wherever you go, they make it? Even past the first apartment in New York and moving to L.A., and back home to where I am now in New York, I still have the book. That was really a big deal. Then I worked on a radio station in college, and they had a collection of albums that you couldn’t play.

VINYARD: And that was in the stack?

TIROLA: That was in the stack. That’s Not Funny, That’s Sick, which was the great Sam Gross frog coming out of the kitchen in the French resturant which says “Frogs legs is the special,” and he’s got no legs left.

VINYARD: Which you animate at the very end of the movie.

TIROLA: Exactly, so you get a little surprise for turning the last page of the movie. So I took that album. They were like, “You can take these, because you’re not allowed to play ‘em.” It had Bill Murray, and Gilda Radner, and John Belushi on it, and that was just…that actually led me to buy an Eddie Murphy album, Richard Pryor album, comedy albums when people actually bought comedy albums.

VINYARD: How’d the documentary come about? The last thing you did was HEY BARTENDER, so what happened after that that led to this, because I believe this is your first showbiz doc?

TIROLA: Yes, it is. After I made my first movie, I produced a movie called MAKING THE BOYS, which is about this groundbreaking play that dealt with homosexuality called The Boys In The Band, which became the movie William Friedkin directed right before he did FRENCH CONNECTION. Very much like STONEWALL now, when the movie came out, the homosexual community boycotted it. That had a certain showbiz flair to it. I’d say HEY BARTENDER has a teeny bit of showbiz, in terms of these bartenders.

But what led to this is one, obviously I loved the Lampoon, and some things had happened that had reminded me that the Lampoon had a greater influence on my worldview than I had thought, especially in terms of the idea that there’s just no restraints on what you can say. Now, living in a little bit more conservative suburb, I’ve had a number people say to me, “You’re always going too far, Doug! I can’t believe you said that! Mr. Dangerous!” And I’m like, “Dangerous? What are you talking about?? I’m the least dangerous person!” I really thought about that, and that led me to thinking about making a movie about the Lampoon. We heard Barbara Kopple, multi-Oscar-winning director, was supposedly doing something, or maybe had tried to do something, but we couldn’t find anything about it.

I had this movie come out called AN OMAR BROADWAY FILM. We premiered at Tribeca, HBO had bought it, which as a doc filmmaker, you can’t do any better than that. Then I had this movie that was just on the festival circuit called ALL IN: THE POKER MOVIE. It won an award at this great festival that doesn’t exist anymore called CineVegas, which was run by a lot of the Sundance programmers, Trevor Groth in particular, Michael Plante. And that was about to go on the arthouse circuit, and Showtime had picked up the TV rights, so my producer said, “Just call the people at the Lampoon.” I went, “They’re not gonna know me,” but he went, “Even if they don’t know you, they know what Tribeca is, and they know HBO and Showtime, and that you’re playing down at the Laemmle in two weeks!” So we met with them, and I sort of said, “Here’s my vision for the movie,” and after a lot of lunches, they finally were able to make a deal.

Which was important, because I had this vision that, if we’re going to make the magazine, this idea, which hopefully works, is that we didn’t have archive footage- we had archive footage that had never been seen of the radio show, and the off-Broadway shows, and images of the people that worked there that have never been seen- if it wasn’t that, we weren’t going to do the more basic, talking-heads, where you lay over footage of something that they’re talking about, but you don’t have that footage, so you get something that sorta visualizes it. In our film, when Doug and Henry go to pitch the idea of a national humor magazine in New York, obviously no one has footage of that, so a typical doc would have someone talking about that and you’d go to the NBC news archive or some other history house, and you’d find grainy footage of people walking around Manhattan in the ’70s, and you put that over when they’re talking. I had had this idea from the beginning, “We’re gonna pretend that option doesn’t even exist. Every time you have the instinct or the need to do that, we’re gonna find things from the magazine.” So some cases, like the example I just brought up, it works pretty directly. There’s a great two-page cartoon called, “Afternoon in St. Mark’s Place in the Late 1970s.” We took Doug and Henry, who were cartoons in the magazine, animated them over that, and that becomes the big New York establishing shot, which I think is pretty clear.

Then you have some things that are more asking the audience to dive into the idea, so when you have the scene of Doug Kenney, like we used to say, “Doug having too much fun,” in Los Angeles, where he’s getting the success of ANIMAL HOUSE, doing way too much cocaine, and talking about that ride, I decided to use this piece called, “The Rich, Pretty Person’s Game of Life.” It’s an imaginary board game where you move around the board doing things like going to discos, and calling a friend from a restaurant for cocaine, and feeding your pet room service in a hotel, and having sex on a big bed in a hotel on Sunset Boulevard and doing too much cocaine. There’s like ten references in this. We were like, “This is how we’re gonna tell this.” Again, a more typical documentary would go into a dark room, and shoot baby powder with a filter, and get this hand. The idea was that this would do a couple things: one, it would keep us in the Lampoon era, the ‘70s and ‘80s, because we’re seeing things from the point of view of the art of the time, but it would also allow us, once we finished talking specifically about the magazine, to continue having the images from the magazine in it. You really feel, as I would say, not to overstate it, but you’re in this FANTASIA. You’re just immersed in this world, like when WIZARD OF OZ goes to color, throughout the movie.

I’ve been very lucky to produce some excellent films that are pure, cinema verite made by filmmakers that are much more artists than I’ll ever be, so I’m aware that for some people, you see an old guy in a chair in the first three minutes of the movie, and, “Oh, talking heads movie! It sucks, I’m outta here.” But for our movie, there are a couple things. One is that some of these people are well known, so it’s interesting to see them. I had the advantage to meet with all these people before we interviewed with them, or at least spoke to them on the phone, not seeing their age- when I say that, I mean they seem much younger, they’re animated, they’re alive. My feeling was that if we followed them around in today’s world, it brings us to 2015, and I want to stay in 1975, or therabouts. By shooting them in these big frame shots, not your typical overlit, “Here’s the close-up, wide-shot,” beautifully lit, almost like a TV show room with the obligatory plant and lamp behind you. We asked everybody to shoot in their homes, or where they worked. You see that these are people surrounded by books, by music. They’re at their artist table. Except for one guy, the hippie art director who we shot at Venice Beach, which works in its own way, but again, big wide shots. These guys are giving performances. They’re telling the story in real time. Usually you see this talking-heads thing, there’s all this commentary, and people rolling back to the old days. No one compares this to now. Even the people that didn’t work on Lampoon, like Judd Apatow, Christopher Buckley, John Goodman, or Billy Bob Thorton, they’re talking about the magazine as they read it at that time. It’s not like, “Well, now they don’t do this.” All that is in service of making it feel like a story. Hopefully, you get all the politics anyway.

VINYARD: I think Matty Simmons is the one who says, when you start to get into later parts of the Lampoon story, that “I’d rather not talk about this,” and I think that’s in reference to the dilution of the brand over the past 25 years or so since the company got bought out.

TIROLA: That’s a great question. We end the movie in the late-80s when the last of the original Lampoon people left. The magazine starts to be on the skids. To be clear, I think people put down the mags in the ‘80s, but there’s some great work in the ‘80s. I mean, Larry David wrote a story about a fictional date with Mary Tyler Moore, which is awesome, because she’s a great looking lady, and he goes into the fantasy of dating her. There are other things, but that’s just an example. It’s sorta like James Bond. Some people think Pierce Brosnan is the best James Bond.

But the story comes to an end there. We did do interviews to tell what happens in that period. Tim Matheson we interviewed, who takes over. They did do the LOADED WEAPON movie during that time. People forget, those are pretty good. It’s not ANIMAL HOUSE, but it’s not trying to be ANIMAL HOUSE, and they’re pretty good. Then what happens is someone takes over, and their business model is to license the name out. One thing I wish we could’ve made known by having that section is that the original movies of the Lampoon were all things that came from the magazine, and people from the magazine were working on them. When you get to VAN WILDER, which is maybe the best one of those, and Tim Matheson’s even in it, you start this period where the power of that National Lampoon brand on a movie, specifically when you have things that are about or feel like they’re about college or high school, because of the success of ANIMAL HOUSE, people are getting those because they think, “Well, it’s gonna be a worse ANIMAL HOUSE.” But that was a business model where you could go with a certain amount of money, and get the name and put it on your movie, and I’m sure that the people who were making those movies were like, “Hey, these movies are gonna be okay, and the brand will attract people, and they’ll see it was good even though they wouldn’t have come to the movie without it.”

Unfortunately, they’re not that great. The one with the title I like the most, because it shows the exploitation of it in its purity, is NATIONAL LAMPOON’S MASTER DEBATERS. It’s about a college debating team, so the title works, but right there it tells you, you know, “Master Debaters,” and I think it sorta says it all. Then you get into this thing where two guys from Indiana come, one manipulates the stock, a nice guy, Dan Laikin, who goes to jail for a little bit. The other person takes over and gets arrested for things that have nothing to do with Lampoon, and I can’t remember his name at the moment, but if you Google “Bernie Madoff of the Midwest,” you find the other person (Tim Durham). Now you have two nice guys from New Orleans who have possession of the brand, and I think they are much more in tune with at least honoring the history of what the National Lampoon was, not trying to be what it probably can’t be, and trying to use some of the great resources that the Lampoon has, like John Hughes stories and other things. I mean, there’s pieces of art you could base movies on if you wanted to. I don’t wanna…the people there are trying in a sincere way.

But the feeling was this: if you know the story of ROCKY, there’s a scene, and if you have the soundtrack album there’s even a song, called “The Morning After.” So the end of ROCKY originally ended with a scene that’s very much like NORTH DALLAS FORTY with Nick Nolte begins, which is a scene of Monday morning, where he’s all beat up and has to take a bunch of pills to just function. ROCKY originally ended with seeing Rocky and Apollo in their settings all beat up after the fight. Ending with that would change the tone, or maybe the message, of that movie. My feeling was if you watched our movie with that story, which really becomes a business story, not about creatives or artists or writers or drinking and fighting and trying to create great things, but a company trying to stay alive story, that’s for CNBC. I would love to do the one-hour CNBC version of that story. But it’s a totally different tone. If you had composition, a lot of the music in the movie is pop songs, but you’d have different pop songs, a differnet composer. It’d even sound different. So my thinking was that if you compare it to ROCKY, not that anyone would ever compare, except myself, National Lampoon to the ROCKY story, it’s like they achieved all this stuff, and when the movie ends, they don’t exactly win, because the thing is fading, but ROCKY didn’t win that first one. It ends with this sort of, “Look at what we’ve accomplished.” That’s what our story is about, what they accomplished, that special period of their life, and they went through all these challenges, so there’s enough drama there for a movie already.

But to put that on the end of it- and I tried it. I had 10 minutes that came after, but 80 minutes of all this stuff, then you end with these 10 minutes. I even did a scene to “Holiday Road” to get all the information really quick, and disguise it with Lindsay Buckingham, ‘cause people love it. I love “Holiday Road,” it’s a great song. It’s a great movie song. It’s just “wah-wah-wah” at the end, where you kind of want to feel more reflective and emotional.

VINYARD: Celebratory…

TIROLA: It’s a bittersweet celebration at the end. I always used to say, “I hope we get a song we can afford,” then luckily, the music supervisor made this great deal so we could bookend it with “Holiday Road.” I don’t like it when music’s used in movies to condense things into one, and “We’ll put a great song over it!” Music, especially at the beginnings and ends of movies, sort of adds something. You feel something at the end, and you would’ve felt something different if we’d added that onto it. People can find that story online, or I’m sure it will be on our DVD, but it was a huge decision not to have it in there, because I knew that people would be like, “What about all that?” But it’s just a different part of the story. What happened there, it had just run its time. I think something could’ve happened to make it survive, but it was just too far gone at that point.

Then they brought someone in who…people might argue that Matty Simmons wasn’t a creative guy, but he had an appreciation of it, and he had written a book, and he had done some things, and he came from more of a showbiz PR background, and the next guy was an executive at Disney cable. The thing that he’d done which is probably the best known is the DORF Tim Conway videos. Go look those up; Tim Conway did these videos where plays a dwarf named Dorf who teaches you how to play golf. I’m sure people loved it, but if you think about the DORF video running the thing that did “Children’s Letter to the Gestapo”…what’s funny about it is that Tim Conway is from the same town as Doug Kenney, Chagrin Falls, Ohio. And I’m sure Chagrin Falls was much more proud of DORF than Doug Kenney, at least at the time.

Also, at one point, I remember saying, “Do we give up like 30 seconds of Gilda Radner for NATIONAL LAMPOON’S MASTER DEBATERS?” There’s just so much. If someone would let me do the Ken Burns version…if Ken Burns would do one of these long movies with, you know, nudity and cocaine and David Bowie music, then we could do like the 9-hour PBS version of this.

VINYARD: That sounds great!

TIROLA: (laughs) There’s a lot of stories there, but you have to know your format. Documentary, you got this much time, and you gotta tell the story within that, and not try and tell a story you can’t tell within that, and end up with a bad movie. Ultimately, it’s a documentary, but it’s a documentary movie, and we tried to not lose sight of the movie part of it.

VINYARD: Was there anyone you tried to get that you couldn’t?

TIROLA: Christopher Guest. Bob Balaban, who’s an actor and who produced GOSFORD PARK, he had optioned a screenplay of mine, and we had a TV project at MTV that we worked on together. Great guy, and I’m thinking, “This is where it pays off! All that other work has led me to this casual friendship with this guy, and he’s in all the Christopher Guest movies!” Tried to get Christopher Guest, and I don’t want to misquote him, but I heard, “Christopher Guest is tricky.” I think he said, “I thought he’d want to be in it!” That was the one we tried to get and couldn’t.

Bill Murray we kind of approached, but I think once we got Chevy Chase, I was almost afraid, “We’re going to end up putting Bill Murray in every frame of this thing.” Because it’s Bill Murray, and I love Bill Murray, and he’d be great, but he really has a specific part in this story. I think that’s covered by other people well. Certainly, I’d love to hear what he thinks of the movie!

VINYARD: Especially seeing him and Brian-Doyle Murray together.

TIROLA: I love Brian-Doyle Murray. People forget how good he is as an actor in things. He co-wrote CADDYSHACK! It’s really based on the Murray brothers growing up. I think just seeing a young Bill Murray is good.

But for the hardcore Lampoon fans, Henry Beard was probably a bigger catch than anyone else. He’s energetic as well. A lot of these guys, if they were actors, they play their range down. They’re energetic, they’re giving their performances.

VINYARD: P.J. O’Rourke has a very specific rhythm.

TIROLA: He has a cadence, but I think he’s had that cadence since about 1980. Once he cut his hair, he started to have that cadence. But P.J. O’Rourke plays P.J. O’Rourke perfectly. He’s funny. He performs too, when he’s talking about the high-school yearbook. He’s great. I think he’d make a great narrator to something. He has a very specific voice.

VINYARD: A nature documentary or something.

TIROLA: To me, if you listen to him, he sounds like a three-cocktail version of Michael Moore. If you just hear his voice. They’re both from…one’s from northern Ohio, the other’s from Michigan. They probably grew up like two hours away from each other.

VINYARD: Was there anyone you had to cut?

TIROLA: Yeah, we cut a number of people from ANIMAL HOUSE. I love ANIMAL HOUSE, so we interviewed a lot of people, and then we realized, “This is going to turn into a big ANIMAL HOUSE DVD extra,” because there were lots of stories about ANIMAL HOUSE, but ANIMAL HOUSE in terms of the plot of the movie just moves it forward. It has a very specific role in our Lampoon story. Stories about the making-of and going to a fraternity and getting in a fight, and John Landis putting the Deltas in one hotel and the Omegas in another one, that’s for a DVD extra about ANIMAL HOUSE.

But that would be like Karen Allen, Stephen Furst, Peter Riegert. Stan Lee, I interviewed Stan Lee early on just talking about the artwork and talking about going from a creator to being a boss, which was sort of to comment on Henry Beard, ‘cause you’re doing this thing then you’re a manager, and how difficult that is. But that was cut. Stan Lee was in the NATIONAL LAMPOON movie, there’s something to be said for that.

VINYARD: The artwork is such a key part of the magazine, but I think that ANIMAL HOUSE is the relic of the era that people latch onto the most. Why do you think things like the artwork, the magazine covers, the articles like the one you mentioned by Larry David, the Lemmings show which was recored in both album and video form, aren’t more prominent in pop culture? With folks like John Hughes, Harold Ramis, Bill Murray attached to these things, they could make some money off of this!

TIROLA: I think the unfortunate thing is that it comes down more to the business side of it. ANIMAL HOUSE is owned by Universal, and they’re great at getting ANIMAL HOUSE out there. There’s like 4 different DVD versions of it. It’s everywhere. There’s reunions, there’s all sorts of things. It’s just in the era where if a TV show was off the air, the only way you’d see this was at the Paley Center, but now they’re on DVDs. Everything’s on DVD, even stuff that was on for two seasons. The translation of magazines to that format, to a digital world, just has not done well. There was like a CD-ROM, like what the hell is that? It had all the magazines with a big watermark on them, and it’s not that great. Lemmings the recording isn’t that great. I’m hoping that the movie will…if you wanted to get Led Zeppelin’s music, you had to go to a used record store and find their albums, and some of their best songs were on B-sides to 45s you couldn’t find, and suddenly there was this invention of the box set, where someone curated this great thing. Hopefully, someone will figure out between the magazine, and DISCO BEAVER FROM OUTER SPACE, and all these things, and put them together in a way that’s relevant for now. But I think they were licensing the name when someone else might have been saying, “What about a great book of John Hughes short stories?”

VINYARD: The most heartbreaking thing for me is that, aside from ANIMAL HOUSE, the other recognizable evidence of Lampoon and their core staff was CADDYSHACK, and when you see and hear about Doug Kenney putting himself out there as the sole producer of CADDYSHACK when the movie wasn’t well-received. Which, circa-2015, sounds ridiculous.

TIROLA: I’ll give you a personal example. I get that. There’s so many independent films made a year, right? So we’ve gotten films that have gotten really good reviews, and you need a butterfly net to get someone to go see it, or a distributor doesn’t do it the way you thought about it, and it’s supremely disappointing. Then we’ve had other movies where it’s a financial success and you see it with audiences, and the critics don’t like it. And you’re like, “I’ve been in audiences where they don’t even know we’re there, and they like it!” It hurts. You take his particular personality, you add what “not getting a lot of sleep” does, which you can read as “doing too much drugs and drinking,” which amps every emotion up, and it’s understandable why he would have gotten depressed. I personally don’t think he killed himself. I don’t think he got to that level, but you can understand how he became so depressed.

Judy Belushi, in her interview, which didn’t work its way into the movie, she was really insightful. She talked about her husband, John, and the disappointments he’d had with 1941, where he was sort of front-and-center in that movie when it came out, and it was seen as a bomb and not well received. Then he’d done a serious movie, CONTINENTAL DIVIDE, which didn’t get the reaction he wanted, and then he went to pitch something at Paramount and they turned him down and offered him a National Lampoon movie called THE JOY OF SEX. She said a week after that, he was gone. You put it in that context, it’s rejection, and especially when you think it’s gonna be good…like maybe he knew CADDYSHACK was good.

VINYARD: It IS good!

TIROLA: We put that Gene Shalit interview in the movie, because it’s kind of brutal.

VINYARD: And he’s a character.

TIROLA: He’s a character, and it speaks to the era. The stereo cabinets remind you of the era and stuff. But it’s like…you can tell Judd Apatow is a real movie guy, which is awesome, because he remembered the review from his local paper! A lot of people remember the movies, but they don’t remember reviews for movies they didn’t make! If Judd Apatow is offended 30 years later at CADDYSHACK’s review, imagine how Doug Kenney felt that Friday afternoon when the movie came out.

VINYARD: They mention that it was a very loose set, and a very Doug Kenney set. They mention drugs and all that, but that’s probably not as unusual for that time as some of the other stuff that was going on. Did you get any good tidbits about what they were referring to in terms of the unusual production? ‘Cause when you watch it, it seems very unusual. Not incoherent, but definitely loose.

TIROLA: I’ve been on sets where directors play music. Cameron Crowe will have music playing in the background, and it sets a tone. I’ve done that on a scripted film of mine. But usually, you have that counterbalance with this producer who is always like, “Let’s keep it goin’!” If the person who’s in charge of keeping it going is the person who’s creating some of the looseness, that could part of the problem. The clip that we’re going to release- because I’ve been releasing all these outtakes on the internet ‘cause it’s nice to have ‘em live somewhere- there’s one set to be released tomorrow where Chevy Chase tells the story of the Murrays coming to his room at the CADDYSHACK hotel asking if he had pot in the middle of the night, knowing he didn’t, and then convincing him to go to Rodney Dangerfield’s room to try and get drugs from him. So that probably gives you an idea.

What’s great about the story is that Chevy Chase sorta tells it like, “You know, that’s the problem: you don’t have stuff like that nowadays.” I don’t think he’s referring to the drug part of it, he’s referring to the fun of it, being up on a school night doing stuff that you’re not supposed to do. Now, they’d be working on their proposal for a product, and preparing to do yoga in the morning.

VINYARD: I can’t remember if it was P.J. O’Rourke or maybe Tony Hendra who says, “I hope every person gets five years like when we were all at Lampoon.

TIROLA: Sean Kelly. They all said stuff like that, but he just gave the best performance of it.

DRUNK STONED BRILLIANT DEAD: THE STORY OF THE NATIONAL LAMPOON is available on iTunes/VOD, and will be playing at the IFC Center in New York and the Nuart in L.A. this week, with Tirola in attendance for the 7:30 and 9:50 shows at Nuart tonight and tomorrow, Saturday.