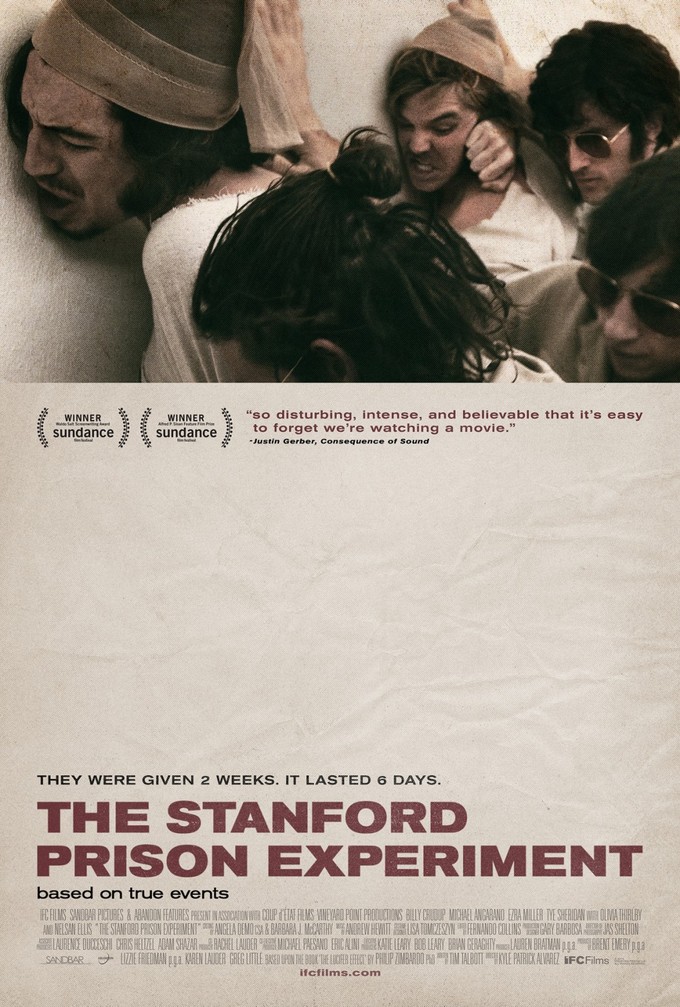

In August 1971, Stanford psychology professor Dr. Philip Zimbardo conducted a study in the basement of a campus building where he and a group of students simulated the experience of living and working in a real-life prison. Scheduled to last two weeks, the experiment was halted after six days; within the first 48 hours, the prisoners had begun showing the effects of severe psychological torture, and the guards (fellow students) were exhibiting abusive, domineering behavior towards their peers. Despite being something of a failed experiment, the study’s been taught in countless introductory psyche classes, and many students are aware of it and have seen at least some of the haunting footage Dr. Zimbardo compiled as he was conducting it.

It’s no surprise that Hollywood’s been banging at Dr. Zimbardo’s door for the past 30-plus years in an attempt to get this movie made; like he says below, there is something inherently dramatic and human about the experiment itself and the results it produced. After all, it was a bunch of young, intelligent men following an older, wiser teacher into a scenario that proved way more complicated and grueling than any of them initially thought. It’s almost like LORD OF THE RINGS or THE MATRIX, except instead of Hobbits or leather-clad badasses, you have dudes with big ‘70s haircuts wearing dresses and stockings over their heads while slowly losing their minds.

Kyle Alvarez film deals with the experience of the study from the perspectives of those taking part in it and those administrating it from behind desks and video monitors, and how the behavioral patterns of most of those involved were quickly, but surely warped and fractured by their participation. Most surprisingly, considering the psychologist professor’s personal involvement, it also highlights Zimbardo’s own culpability and ruthlessness while functioning as the “superintendent” of the makeshift prison. As Billy Crudup portrays him, the doctor’s presented as a man so driven to generate results from the experiment that he begins to overlook and indirectly approve of psychological and physical abuse towards the group of young boys that willingly volunteered for the study, and who keeps the audience’s sympathy at bay with an increasingly cold, destructive obsessiveness. He’s arguably the Machiavellian villain of the piece, and it’s a huge testament to Zimbardo’s objectivity that he not only allowed himself to be presented that way, but actually encouraged it and advised on it himself.

Because of my fascination with the original study and the level of moral ambiguity in Crudup’s portrayal, I felt particularly lucky to get a chance to pick Dr. Zimbardo’s brain a little bit. To prep for the interview, I watched two of his TED talks, one on "The Psychology Of Evil”, which relates to his book, The Lucifer Effect, and one on “The Psychology of Time”. I highly recommend checking out one or both before reading on, as I relate to them in my last couple of questions:

VINYARD: First, I want to get your history with (the movie). I heard a lot of people approached you since you wrote your summary of the study back in ’72. When were you first approached, and what was the path that eventually led to this movie getting made?

ZIMBARDO: The experiment has an inherent dramatic quality, because its the only research in which you can see character transformation. It’s one of the earliest studies that also had video of what was happening. Early on, probably five years after the study, I actually was invited to the Brown Derby, a famous restaurant in Hollywood, to meet with the guy who had just won the Oscar for IN THE HEAT OF THE NIGHT, Stirling Silliphant, who was very much interested in doing a movie about the experiment. He came up with an outlined initial script, and then he went on to do some blockbuster, I don’t know (THE POSEIDON ADVENTURE), and then this was too small a show for him.

After that, there were endless scripts that were sent to me by different production companies that took out options. Leonardo DiCaprio was going to be in the movie once, and then he went and did TITANIC. The movie has long legs, and it was only about 13 years ago that Brent Emery, from a small production company here, Coup d’Etat Films, committed to getting this made. Only three years ago, he put me with a production company who came up with the two-million-dollar budget to make the film. The film was actually made in a very short time. I think it started filming only two and three years ago.

VINYARD: Kyle (Alvarez) told me they were shooting 12-15 pages a day, which is very fast.

ZIMBARD: They shot all the prison guards scenes first, separately in Burbank. They were shooting like 12 hours a day. Then, they shot all the scenes with my character and my staff, and then all the parole board hearings, the visiting day, and so forth, and I was on set for some of that in South Hollywood. They shot all that in less than two weeks. The whole movie was shot in probably a month. In a funny way, doing it that created an intensity. When I was on the set, they went until midnight or 1 o’clock every night! But it was almost like a fraternity feeling, that everyone had made this commitment, and was going to do this unusual thing and do it really well.

Kyle Alvarez is a young guy. He related, on a very personal level, to the prisoners. I can see it now afterwards, as we meet with Ezra Miller and Michael Angarano, who play the most rebellious prisoner and the worst guard, they still have a very personal rapport.

VINYARD: The set and all the costumes are so closely designed to match the footage from the original experiment. Was it bizarre being on set and seeing all this dramatized?

ZIMBARDO: I’m looking at a monitor on the set, and I could not tell the difference. They actually had another monitor from the real prison study, the videos I had made, and you couldn’t tell the difference. They sent the production crew down to Stanford, and spent a day, maybe more, videotaping and measuring every single thing, so things in the movie are within an inch of what they were actually. The only thing was, in order for the drama of the scene, they arranged so that either the ceiling or or the back walls of the cells could be opened so that you get the camera dollying from cell to cell. With that exception, it’s the Stanford basement. The Stanford Jordan Hall Psychology basement.

VINYARD: Was it bizarre to see Billy Crudup playing you?

ZIMBARDO: Yeah. For sure. It’s bizarre to see anyone playing you. Especially the first time I saw it. Somebody’d say, “Hey Phil,” or “Dr. Zimbardo!” I’m sitting up in my seat, about to say, “Yes, what?” But I think he does a very good job. It’s the makeup, but also, he just grew his hair. It’s 1971, everybody had hair. I mean, I had loooong hair, mutton chops. I’ve always had this goatee, this mustache and beard. It’s become sort of a Dr. Z signature. I used to wear a vest like that. They looked at old warddrobe pictures. The big fat tie, you’d wear that when you were teaching. (Crudup) got really into the period as well as into me.

VINYARD: Did you work closely with him?

ZIMBARDO: For a couple of days. He’s a professional. Almost everyone, including a lot of the guys playing prisoners and guards, they’d all read Lucifer Effect. Many of them went to my website, many of them looked at the videos. We had 12 hours of videos, and most of them on PrisonEXP.org, a website devoted to the Stanford prison study, which has files and videos and almost everything I’ve written. Most of the cast, especially Billy, was really well-informed about the reality of that whole thing. Again, it’s acting. It’s not a documentary. They’re not recreating the whole thing. They are interpreting what they think is important as they bring the science and the study into film. And they do a great job.

VINYARD: Kyle mentioned that you were actually writing The Lucifer Effect while Tim Talbott was writing the screenplay.

ZIMBARDO: Exactly, same time. Again, Tim Talbott was hired almost as a writing consultant. They didn’t have the money for a production crew. I think he was hired on contingency of something, and took a chance. He put in a huge amount of time. I think his first script was like 300 pages because he was taking big chunks of what I was sending him and just plopping him in, and they kept saying, “No. Cut it down, cut it down, cut it down.” I don’t know what the final script was.

He was just wonderful to work with. We sent e-mails, he’s calling like, “I don’t understand this, what about this? Can I change this?” Things like that. For me, it was the first time doing it, and at that point, neither he or I had any sense that it was going to be a film. It was like shooting in the dark. “Maybe if we do a good enough script, maybe we can persuade producers to put up the money and make the movie.”

VINYARD: What do you think the biggest changes were as they fictionalized it?

ZIMBARDO: They had to crunch six days into two hours! So there were a lot of very dramatic scenes in the experiment which they couldn’t put in at all. There were a lot of scenes they couldn’t put in because they didn’t have the budget for it.

One of the opening scenes, the police arrest one of the would-be prisoners. The dramatic part was bringing them down to the real police station, to the jail, seeing the prison there, taking the photographs, putting them in a prison cell. That’s really powerful, because everyone knew it was an experiment, but now the authorities are taking away your freedom. It was very different, and that’s why I did it. It’s very different than if the kids came out and said, “Hey, I’m here to be in the study.” If they gave up their freedom voluntarily, at every point, they’d know it was an experiment and they could take it back. But now, really down deep in their psyche, it was police that took away your freedom. It was the police who said, “You are wanted in violation of Penal Code 4592C blah-blah-blah.” Because they didn’t have the budget to go to a jail, they just had a single arrest. That’s one of the things.

When we thought there was gonna be a prison break, that 8612 was going to come back with his buddies, I was prepared to bring all the prisoners back to that jail, the real jail. It was an old jail that was empty. So it was very dramatic, we put bags over the prisoners heads, we put them in cars to bring them down. I persuaded the sergeant to let us do that, and he canceled at the last minute, saying that it would be an insurance problem for the city if anybody got hurt, so we couldn’t do it.

It would’ve been a very powerful scene, and it would’ve shown how crazy I had gotten. I had become too immersed in my situation. All I’m saying is, everything in this film is an accurate reflection. Nothing is overdramatized. If anything, there’s a lot of drama that we left on the cutting room floor or that never even made it into the script.

VINYARD: Was there ever a concern about how you were being portrayed in the film?

ZIMBARDO: I didn’t have influence on it. It was a bit extreme. In The Lucifer Effect, I made it clear that, in retrospect, I felt guilty that I had created a trap and then fell into it. I observed human suffering, and ignored it. The only thing I did was say guards could not physically punish prisoners, but I did not say they could not psychologically punish them. Psychological punishment’s worse. If somebody uses physical punishment against you, you get angry. In psychological punishment against you, you develop helplessness, and then you break down. That’s the thing I felt guilty about. If anything, I think there’s not enough of my earlier, more positive persona being transformed into a negative.

The good part is that if you look at the beginning of the movie, when I’m moving in with Christina (Maslach), we’re starting to live together, that is soft. I am, as a character, soft. I’m very loving, romantic. That’s the transformation. So when I’m on the prison set at the beginning, I’m curious, "Will it work? Will it not work?" But then I think maybe too soon the switch is thrown, and I become too negative.

VINYARD: I watched your TED talk about The Lucifer Effect, and specifically the three types of evil you mentioned: dispositional, situational, and systemic. Internal evil, external evil, or systemic evil. What do you think the experiment was most indicative of, in terms of how the guards were acting, how the prisoners reacted, and how you were acting as superintendant?

ZIMBARDO: I’m glad you picked that up. In general, when there is some “evil” event, we always say, “It was a few bad apples.” This is what Bush’s administration and the military said about Abu Ghraib. Whenever there’s a scandal at the police department, the fire department, the schools, it’s a few bad apples. What that does is it takes off the hook, “What was the situation that they were in?” And then it really takes off the hook, “Who created it?”

I think I’m the first one to say you really have to have nuanced analysis when something goes wrong. How much do the individuals involved contribute? How much is it that those people were just trapped in a situation where anybody put in there would do the same thing? Where is the real power? It’s legal, it’s economic, cultural, historical. When you want to change individual behavior, it’s not enough to do therapy, it’s not enough to put them in prison. We have to change the situation that promotes that behavior.

Ultimately, the hard thing is we have to change the situation. When the economic crash came, it was all systemic. It was all big banks, it was all federal regulations, it was accountants. There’s not any one person that causes worldwide disaster. The sad thing is that nobody ever went to prison for it, which obviously they should have.

VINYARD: In terms of time, do you think the guards and prisoners were thinking in terms of Present (Fatalism), and that’s sort of the trap they fell into?

ZIMBARDO: Oh, sure. What made the study worse for the prisoners and guards is they were living in the moment. They were living in the Present (Fatalist)-ic moment. They never talked about their future or their past, so they were trapped. Psychologically, they were trapped in the moment, and the moment was horrible. Physically horrible, psychologically horrible. So they made it into a psychological prison.

VINYARD: We currently have the highest incarceration rate in the world. Do you think there’s anything that could be done to make it less of a hopeless situation for the people inside?

ZIMBARDO: Absolutely. Just today, President Obama became the first president in American history to visit a prison. He is actually beginning to call for prison reform. Valerie Jarett, his aide, was my student at Stanford. I gotta get her and say, “Hey, have a look at this movie!” (Dr.) Craig Haney, who is my graduate student, is the leading prison litigation lawyer. He was involved in the Supreme Court decision that solitary confinement is cruel and unusual punishment.

There’s so much that can be done, but you have to begin by saying, “We gotta change the law.” We gotta change the three-strikes law. We gotta stop putting black men in prison for using methamphetamines, etc. So there’s lots that could be done. The disgrace is that 2.3 million Americans are in incarceration. That means millions of our dollars of taxpayers’ money thrown away because prisons don’t rehabilitate, prisons don’t reform. They just produce angry men who’ve been abused for years at a time

THE STANFORD PRISON EXPERIMENT is currently playing in limited theaters around the country, and is available on VOD.