Not to be snide, but most “coming-of-age” movies these days are total bullshit.

To be fair, it’s definitely a tried-and-true genre, but I mostly find them lacking, either too cute and unbelievable or simply too steeped in pretention and a misplaced sense of nostalgia. Even some of the ones that are purported to be autobiographical tend to scream of artifice, sentiment, and an overly precious depiction on what it’s like to be young and confused, and those first moments where the complexities of life seem to make some sort of subjective sense.

Not Morgan Krantz’s BABYSITTER.

His film is a darkly funny, yet wholly believable story of a teenager named Ray (Max Burkholder) who is caught between his parents, a successful filmmaker and a former actress, as they battle through a messy divorce. His younger sister is too young to realize what’s going on, but the shallowness, pettiness, and greed of the divorce proceedings are clear as day to poor, pot-smoking Ray, and is only making his sense of alienation and disillusionment stronger by the day. Enter Anjelika, the daughter of a late singer who Ray’s mom hires as a live-in babysitter for his sister. The mysterious young woman is all shy smiles on the surface, but she secretly backpacks around a Wiccan spellbook and some grade-A marijuana, and it’s not long before her and Ray create a tenuous, yet increasingly intense bond that creates all sorts of implications in both of their lives.

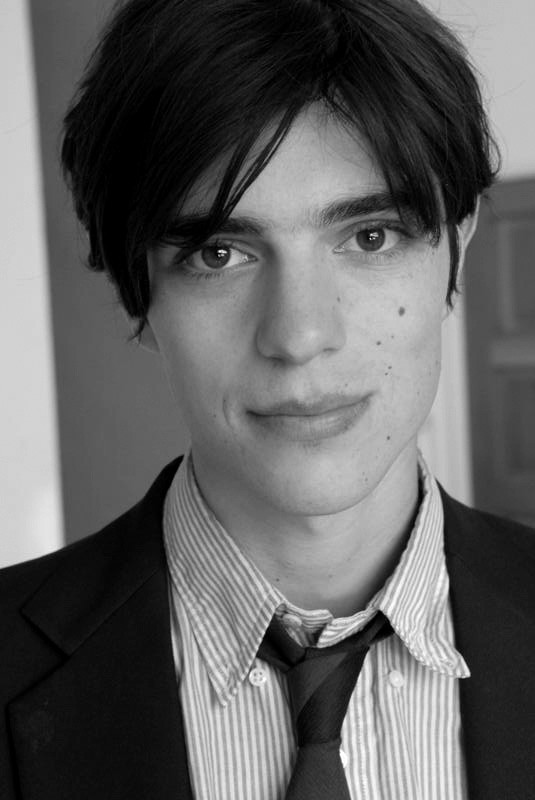

BABYSITTER is remarkable in it’s uncondescending, sometimes hard-to-swallow portrayal of its adolescent protagonist, and the “love story” that unfolds between him and Anjelika is believably messy and all the more powerful for it. It’s a terrific feature debut from the impossibly young-looking Krantz, and an equally powerful showcase for its cast, especially Burkholder.

I got to chat for the better part of an hour with Krantz and his producer, Luke Baybak, about how they shot the flick, what they’d learned, and how they achieved the sense of honest intimacy that gives the film much of its power and charm. Be warned, there are some light spoilers re: the film's ending later on in the discussion.

VINYARD: You guys worked on this movie, now you’re showing it around. What’s the experience like watching it an audience? What’s it like putting something that personal on the screen and then watching it with festival crowds again and again, doing Q & A’s and stuff like that? Has your feelings towards the movie changed at all?

MORGAN: There’s always a rock in your shoe about something, I think. In terms of the personalness of the film, I think it’s natural for me. I’m pretty open with people about things. I’m not like a super-private, cagey person, so it doesn’t feel particularly out of the ordinary to have my underpants shown, you know what I mean? There hasn’t been any instances where like I’ve been offended. I feel like even if it was less obviously personal, it still wouldn’t feel that different.

VINYARD: You mentioned some of your influences in the Q & A, AMERICAN BEAUTY and domestic dramas like that, but I couldn’t help but assume that the film was, some level, autobiographical. Was it at all?

MORGAN: Yeah, definitely. In the characters in the feelings, I think, but not necessarily the events. The people are all kind of based on people…my mother was going through a divorce, not with my father, but with my sister’s father. I was around Ray’s age, so I kinda just remember the nastiness of that environment. It’s like a composite of a bunch of things. I did lose my virginity to the babysitter.

VINYARD: It was funny to hear you describe Ray as, “a little shit.”

MORGAN: I find him very sympathetic, personally. He definitely is a shithead in a way that I find endearing.

VINYARD: But you also follow that up in the film by saying, “Everybody in the film is kind of a shithead.”

MORGAN: Did I?

VINYARD: Well, not like a shithead. That was a different question, but when someone asked about the nastiness of the female characters in the film, you said, “Well, the male characters aren’t much better.” How was that in terms of writing?

MORGAN: That’s a perception I have now showing it to people, but when I was writing, I was in love with all the people. I like all of them. So I was never writing down to them, or trying to mock them. Some things came out more satirical than maybe was intended, but I was always trying to be inside of their head, not like judgmental. After showing it to people, you get people’s perceptions of it, and then you go, “Oh yeah, I guess he is kind of a little shit,” and stuff like that. That was an after thing. That wasn’t in the process.

VINYARD: The performance of Ray (Max Burkholder) really did pull me into the film. He’s in every scene of the film, and we see everything through his perspective, and I never did get that feeling that he was “a little shit,” maybe because we were seeing it through his eyes.

MORGAN: You shouldn’t have! I guess that one guy did…that’s something that comes from parental audiences, and a lot of females that have watched it, you know? I don’t feel that way. You’re meant to view Ray nostalgically. We’re a little more aware of him than he’s aware of himself, which makes for a kind of specific viewing experience. Even though his decisions are big decisions- it’s a movie about kids for adults. So as an adult, you’re obviously drawing parallels between what’s happening in his family, what’s happening with his babysitter, and his mother, and these are things that he’s not thinking about. That, to me, is part of the pleasure of watching it, having more of a psychological insight into him. I think we all look back on our childhood, and in retrospect, we come to the realization like, “Oh yeah, I probably did this because of this,” you know? Things you definitely didn’t know at the time. I guess it still happens. In 10 years, we’ll be looking at this, and being like, “Well, it went this way maybe because of this,” you know? It’s meant to be humorous in that reflective kind of way.

VINYARD: How old was Max when you guys shot?

MORGAN: 16.

VINYARD: So how did you communicate this stuff to him? ‘Cause presumably, he’s of the same age where he doesn’t have that level of insight, etc.

MORGAN: He’s pretty smart! He’s not at all like the character. He’s also been acting since he was like three or something, and he’s really good. He’s nothing like the character, he’s a total invention. We communicated very candidly. Totally transparently. I could give him very directorial notes that were like about beats and the rhythm and stuff, and he’d be like, “Oh, yeah. I got it.” He’s very professional. Once he clicked into it, it was easy. It was never like I was talking to a kid. The only times it was like that was when he brought a certain authenticness or genuineness into certain scenes. For instance, the scene where he presents himself as the new drug dealer to the current drug dealer in the school, his take on that was very much like in Ray’s perspective, which is a testament to how invested he was. I was really more interested in the awkward humor of it. He was like in SCARFACE, you know what I’m saying? Things like that, where he was so invested in the character that I’d have to have conversations with him about the tone, and make him understand why it was funny, ‘cause in his mind, he was like, you know, taking over the school!

VINYARD: How did you find him?

MORGAN: We just auditioned. We auditioned like 100 kids. We had these amazing casting directors, Danielle Aufiero and Amber Horn. We boiled it down to two kids, and I did my due diligence to figure out which one to go with. I don’t know what this means or anything, but both of the kids had my birthday! Weird. Which wasn’t why I went with them or anything. I just took it as a good sign.

Our other choice for the role was a more comedic-minded actor, which I love. But I think Max was great because he just approached everything very straightforward. He played it all very straight. He was never trying to go for a laugh. If anything, I was trying to coax him into certain things like that. But I think it was much better to start in a place where he was just trying to keep it real, know what I mean?

VINYARD: Did you test him and Danielle together?

MORGAN: We did a chemistry read, and it was pretty awesome. They have great chemistry.

VINYARD: She mentioned in there that there was some concern from both you guys about playing her as “the magical negro.”

MORGAN: Well, we intentionally play her as “the magical negro,” and then wee rip it out.

VINYARD: From a story perspective, what was the purpose of putting in the Wiccan stuff? Why add that to her character? It’s a very interesting touch.

MORGAN: Thanks. The basis of the character was…I always imagined her before he walks in the house, she just had a very tough time, motherless and all that. I just wanted something to express the fact that she was trying to have some control of her life. Presumably, she’s kind of like this orphan, and I just feel like when you’re in that position of ruin, you’re gonna grab onto something, religion, or drugs, or a person, or Wicca. I just thoguht the movie was vaguely supposed to be in the ‘90s, and THE CRAFT was very big, and I remember girls being into that stuff. It’s interesting for a black girl to be into it, because she’s a black girl, but she’s a black girl who was raised in L.A. in the entertainment industry. She wasn’t raised among other black people, you know what I mean? That was kinda the thinking behind it.

The “magical negro” thing is interesting to me, because I sort of caught myself writing it. I caught myself doing the cliche, and then I was like, “Oh, this is bad!” But then we figured out a way. I like the idea of introducing an archetype that you know, and then kind of twisting it. Particularly this archetype, which is like offensive. Some guy came up to me right now and said how mad he was at the beginning, when he pulls out that Wiccan spellbook, and it looks like we’re going fully for the magical negro thing, and for the first two-thirds of the movie, or the first half, we are in the magical negro thing. I always thought of her having identity issues, with her family and stuff, so I thought it was cool to have this black girl who was essentially pitching herself as the magical negro, you know what I mean?

I think people do that. If you walk into a new situation, we grab the nearest archetype to try and present ourselves, to try and make ourselves as adjustable as possible, you know? So I thought that was cool that she was really the one responsible for this perception of her.

VINYARD: All those songs in the movie, they’re original songs, right?

MORGAN: Original songs by Josh Grondin.

VINYARD: Cool. How was that like? How many did you get?

MORGAN: Two original songs, outside of the score. That’s a great story, actually. He made the songs early on, and we recorded a girl doing it and it was great, but it wasn’t the right vibe at all. It was just like a friend of ours. We tried casting singers for like several weeks, and we just couldn’t find one. Luke had an idea to go to a gospel church:

LUKE: It was like Saturday, like two in the morning, and we were on a huge deadline.

MORGAN: This was like three weeks ago. No joke.

LUKE: And we were like, “What are we gonna do? We need the right singer!” And we were searching, trying to find it, and we were like, “Let’s just go down to Crenshaw and find an amazing gospel singer.” So we put on suits, and we went there, and ended up finding this girl who’s really cool and awesome and has a really cool voice. She came that night and recorded the tracks, and we really felt it in the room. She really threw it down. It was awesome.

VINYARD: It sounds like a 20-year-old song.

MORGAN: Josh is super talented. I originally just brought him on to make those songs, ‘cause he makes music music, but he’s never done a film. But he did those songs, and we had such a good time collaborating. The first time he sent me anything, i could tell that he cared a lot. His conversation’s really nice. After he sent us two songs, then I asked him to do the whole score. I think he did a really amazing job.

VINYARD: It’s a coming-of-age movie, but it’s a coming-of-age movie with werewolf effects. Pair of questions. A. why did you feel you needed to put that in the movie from a story perspective, and B. can you talk about the technical aspect of working with makeup effects?

MORGAN: On a story level, I felt like the movie needed something to elevate it, and sort of enrich it in some way. I really like surrealism. That came in the second shoot. We did a few legs of shooting. The whole story of the werewolf was a speech that Ray says in the film, just a normal speech. I kept moving it around in the cut, and I never knew where to put it, but I really liked it, Then one night, we sat back to watch the cut before we went to do more shooting, and I just kind of had the idea. Perfect collaboration, because Luke was talking about adding voice-over. I think it adds perspective. It adds a subjectivity to the film, which I think is needed because the film is very real, but also takes liberties. Not in the acting, the acting’s all very natural I feel, but the story structure is subjective and I wanted it to feel subjective and singular, and that helps that. By essentially starting the film in his mind, more or less.

VINYARD: And he’s not a glib guy, but he’s already told you something about himself.

MORGAN: Yeah. And I think it’s funny, the concept of seeing his mother get eaten.

LUKE: Making the werewolf head is a cool story.

MORGAN: I acted in HOUSE OF LIES, the Showtime show, and they had to make a dick for me, a prosthetic. I played an old high-school boyfriend of Kristen Bell, so I had this whole dick made and stuff. It was a very weird experience, very funny scene. Obviously, the guys who made the dick for me and put it on me and stuff, we got very close. We build a rapport, as you do when people put dicks on you. When the time came, we had zero money, and we were literally shopping on Target.com, looking at these horrible costumes. I called the guys who made the dick and went, “Hey, it’s Morgan,” and they remembered me, thank god. They had this intern…they said he was an intern, but the guy actually has five years experience here in the film world in Austin, just moved to L.A. Benjamin Ploughman. It was so lucky. It was just a real blessing, ‘cause they just threw him at me, we spent a week talking about it a lot, and after the initial conversation, he just went to work. They let him use the labs there. He really nailed it. It could’ve been so bad! It could’ve been really, really bad.

VINYARD: You shot in L.A., and I thought it was a very unconventional way you lensed L.A. It didn’t feel like an L.A. movie. Was that deliberate on your part, to shoot L.A. in a different way?

MORGAN: It’s hard when you picture a story in L.A. I picture the worst version. I wanted it to feel like intimate and specific. We didn’t have the budget to close down streets and go to the locations I find very special in L.A., so I was really trying to keep it more about the faces. I liked the palm trees, showing palm trees in a way that’s not sunshiny palm trees, the classic driving down Sunset Blvd. pointing up at the sky thing.

VINYARD: Randy Newman blasting.

MORGAN: Exactly. I wanted to avoid the Randy Newman of it all. We shot a lot on tight lenses. My favorite scenes are the ones that are like really dark, the night scenes. L.A.’s so big. You’ve probably seen LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF. There’s no one way to shoot L.A. It’s so big, and it’s not even a specific place at all. There is no specificity to L.A., which is why everybody shoots there. That’s why L.A. became L.A., because of the oceans and the deserts and mountains and stuff.

LUKE: The Valley sort of has a different feel.

MORGAN: It takes place in the Valley, and the Valley just sort of feels like any weird ‘burb. It was all about the performances and the faces anyway.

VINYARD: There’s a lot of pot use in the movie involving teens, which, as a teenager who smoked pot, I completely understood and believed. But like you said, there were older people in the audience who were a little turned off by some of the behavior.

MORGAN: They were concerned.

VINYARD: Was that ever an issue? Was that intentional on your part, to show teenagers in a way that is more attuned to what’s actually going on, rather than the cutesy stuff you normally see?

MORGAN: Yeah, I hate cute. Hate cute. That was my experience as a teenager. I don’t smoke weed, actually, so the weed for me was just Ray…as a teenager, I just used weed as a manner of connecting. It’s your flag, like “This is who I am. I’m the weed guy. I smoke weed, I listen to rock and roll.” It was much more about social dynamics than it ever was about getting high. That became fun too, of course. That was just my experience growing up, so I wasn’t trying to water it down.

VINYARD: It also adds to the intimacy of the night scenes that you were talking about. How did you get everybody in the mood to be more relaxed, and get in that state of being very open and very honest? Was there any improv at all between Max and Daniele?

MORGAN: There’s very little improv. I do a lot of series, so I would throw a lot of lines and shoot series. Very little improv, but I think a good way to keep it loose and keep people relaxed is to be super transparent. As an actor, that’s really the only thing I know how to do, is to be really transparent. Maybe too much. When you’re watching it, you just have to be really honest, and say, “I don’t know, I don’t like it.” You don’t have to know why. I hate when the director is withholding information. I hate when they’re perceiving something, and they’re trying to twist it in a way to get me to do what they want. I’d rather they just tell me, “Yeah, I’m not feeling it, I don’t know why.” Then we can discuss it. I think that keeps everybody pretty chill, because it doesn’t make the actors feel edgy, it just makes them trust you. They will let you know if it’s not working, they’ll say so. And I’ll help them figure it out.

VINYARD: Besides that, what did directing teach you about acting and being an actor that you didn’t know before?

MORGAN: Certainly, when you direct, it enriches your acting. I cut it too, and in cutting I think I definitely became a better actor, because you spend hours and hours just watching performance and marking the moments that you like, so it just sharpens your taste, you know what I mean? You watch movies all the time, but those are selects. When you watch like ten takes- I shoot a lot of takes- whatever the ratio is, you mark every moment that appeals to you, and you learn something about what is good acting I guess.

VINYARD: Was there anything you wanted to keep in there that you ended up having to jettison?

MORGAN: Yeah, there were so many great scenes. We shot like really sprawlingly, and there was some funny stuff that didn’t make the cut. There was a scene where they find the movie in her car. She slept in her car with a guy that she met, and they find her sleeping with some dude she just banged. My neighbor was this great actor who played the guy, and it was a very funny scene, it just didn’t fit anywhere. I hope to exhibit it somewhere, because it’s funny. But we didn’t need it, and I guess the rule is if you don’t absolutely need it, it’s got to go. There was a lot of stuff like that. A lot of moments from the actors that I wish I could put all of them in, but you only have so much real estate.

VINYARD: What about your next go-around as a director? A. specifically what are your plans, and B. what will you do or what won’t you do that you did or didn’t do?

MORGAN: I have two projects. One, I made this webseries that I act in and made with my friend Alex Mirecki called NEUROTICA, which we just sold to Endemol. It’s fun, and they’re financing a second season, so we’re making that. It’s a really funny and crazy webseries. I have a movie that I’d like to do as soon as possibile which is similar in tone to this, but is more about fathers and brothers and men, you know? I’m really excited to start writing, actually.

I think there’s really an infinite number of lessons I’ve learned. I keep meaning to sit down and like write them all out for myself so I never forget. I think the big thing that I want to apply is…there’s so many levels of it from every perspective, but from a craft level, I think the lessons I’ve learned about story structure and the audience’s relationship with the characters is something I don’t think you get until you make shit. Every time you make something, you learn more about that. I feel I’ve learned more about empathy…I think I might be better next time at manipulating the audience. I found there was huge gaps between how I perceived the scene while making it and how the audience perceived the scene. There maybe still is. I’d think something was hilarious, and you’d find that the majority of the audience finds it sad, or something.

For instance, when the father breaks into the house with a video camera, I think it’s very funny, but people seem to take it very dramatically or heavy. The original ending I shot for the film was different in a big way. The babysitter brings the cops, and this whole thing, and that was the original thing we wrote. What I realized was that, in my mind, I thought, “Oh, isn’t it sweet that she left the deposition to come do this,” and all that. What I wasn’t counting on was that people are buying into her and care about the characters. It was kinda news to me. I didn’t expect people to care as much about the characters, and I didn’t realize, “Oh they’re going to care about this girl so much that if you throw her in jail, it’s really gonna bum people out.”

It’s a hard thing to describe, but the understanding of the fabric of the audience relationships is something I think I’d advanced on a little bit. One thing I think as a director is trusting your taste in people is very important. I think there were a lot of victories in this way. But of course, in any situation, there are missteps as well. It’s just about trusting your taste. I feel like when you write, you’re just in this bubble. You think you’re a genius, and you’re totally willing to take all of these risks and not give a fuck, and suddenly you have money, you have people, they’re asking questions, all very heavy, and it’s like this avalanche. it can crush you. From the shorts I’ve done, I’ve become less and less crushed. I let those pressures influence the creative decisions less and less. But if I look back on stuff I made a long time ago, I see how that pressure caved me in, and made me go for something that was easier, or clearer, or more accessible, and I think you just get more and more resilient to that I hope.

I think next time around I want to take bigger risks, and be even more single-minded and less pandering. Not that I feel like I was in this movie, at all. I think I did a good job of protecting this film from those pressures. ‘Cause when you put a black girl in a maid’s outfit and your movie isn’t about slavery, people are asking quesitons! And you start to think, “Oh fuck, man, I might get fucked up for this!” You know? You think people are gonna see this and be like, “You’re racist,” then what am I gonna say?! It’s super weird. The personal elements of the film too, it could just be this diary movie, and all that stuff. There’s nothing you can make that some fears don’t enter in, and whatever weak spots you have will be brought out in making a film. You just hope they become less weak next time.

VINYARD: I’m a huge fan of CLUE, so seeing Leslie Ann Warren show up at the end was awesome. Why’d you go with her, and what was it like landing her?

LUKE: She was one of the few that actually didn’t end up auditioning, understandably.

MORGAN: She’s Leslie Ann fuckin’ Warren, man!

LUKE: She was just super into the story. Her and Morgan hit it off right away.

MORGAN: When I first met her, she literally opened with a story about dating Bob Fosse. I was like, “Alright, I just wanna hang out.”

VINYARD: “More of this.”

LUKE: She’s been great. She came to our premiere, she’s been super supportive of the movie. She’s been acting for a really long time, and it’s awesome to have her just doing an indie movie. I think she was rolling with it, and I don’t want to put words in her mouth, but I think she also got a good experience. Having been in the industry for so long and having been part of so many different things, this was like a new spin on it. i

MORGAN: She’s very hip, she’s super hip. I don’t think she was quite prepared for how indie we were, and I don’t think we were prepared for how unprepared she was at how indie we were. I think it’s awesome she’s so open to working with a first-time director on a script that’s kinda weird and everything. She was really open to it. She has really good taste too. The things she liked about the script were the things I liked. She’s just cool, man. I think it’s awesome and smart to do this. I think a lot of actresses her age aren’t down to do that at this stage, so it’s very cool.

VINYARD: You said that there was a break in the shooting where you watched a cut of the movie and filled in some blanks. Can you talk about the shooting schedule?

MORGAN: We shot the movie for 16 days.

VINYARD: How much was in the can at that point?

MORGAN: Like two-thirds. We shot a lot really fast. 5-9 pages a day, which is a testament to the cinematographer who works really quick and made it look great. Then we cut for a while, and BOYHOOD is the prime example of why this is beneficial, because every director wants to do this, and if you can swing it, you should. To do reshoots I mean. You can look at a script, and tere’s only so much you can get from the script, but if you can actually start working with the material of the film which is the film, so like cutting the actual shit together…I don’t know if this is healthy or not, but I think it works. I always regard the film as its own thing, and, “This is what the film wants.” It also let me off the hook, so when I go to Luke, I go, “Well, the movie wants this, man! The movie told me this is what it wants! I am only the vessel!” You know? But honestly, without being too pretentious about it, it’s how I really think about it. I just watch the movie, and listen to it. A lot of people do this with shorts too. If you just sit back and listen to the film at a point where you still have the ability to shoot more, I think it’s awesome. It’s nice to be loose that way. I also didn’t go to film school, so I have no preconceived notions that like the script I wrote was perfect. I am very willing to acknowledge what I don’t know, which is good and can sometimes be bad, you know? I just take it all from the movie, so I just watch it and be like, “Oh it needs that.” It was a really great experience, and Luke was the one that made it happen and got behind it. It’s an awkward conversaiton when you shoot all this stuff and you champion it, like “This is the fuckin’ movie, this is what it is, and I need this and I need this and we’re gonna spend so many thousands of dollars,” then you have to go back to your producer and be like, “Yeah, so…new idea.”

VINYARD: “Can we get a werewolf mask?”

MORGAN: Yeah, especially that idea. “Actually, we’re gonna close this out with a werewolf.” I actually sat on that epiphany for a week, because I was so scared, but it’s a testament to him, because as stressful as it probably was for him, he saw that it was good, so he made it happen.

VINYARD: How did you guys pitch the film to financiers?

LUKE: It was like, you know, friends and family. we had a lot of private investors, equity type things. It’s almost like Kickstarting the movie, but Kickstarting it to a ton of individual people. When you see a Kickstarter page with all the information, and the whole pitch pack, and videos, and everything to give them what’s that like. It’s the same thing. To Kickstart something, it takes a lot of time and energy, and you can’t just put something and be like, “The money is there!” It’s a similar thing, you just have to Kickstart individuals.

MORGAN: But it’s just as much work. You can nickle-and-dime all these business guys, or you can go on Kickstarter. Because even after, “Yeah, we’ll give you a couple of bucks,” you have to follow up, you have to get it.