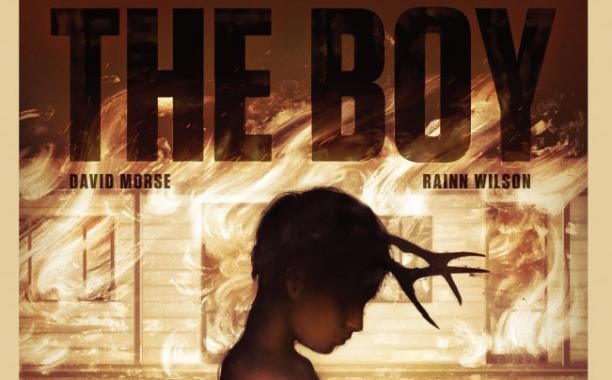

THE BOY, dir. Craig Macneill

Some will describe THE BOY as a horror movie. I don’t know if I’d necessarily agree with that. Sure, it was produced by Chiller Films and Elijah Wood’s SpectreVision. Sure, you could argue that there’s a creepy, foreboding tone during much of the film. And sure, some stuff eventually goes down that is certainly familiar to the horror genre. But this is something else. It’s even less of a horror movie than something like Jim Mickle’s WE ARE WHAT WE ARE or SpectreVision’s own A GIRL WALKS HOME ALONE AT NIGHT, which lull you in with their genre trappings and end up working on their own different, surprising terms. Not THE BOY. Even at it’s most horror-y, it never stops feeling like an intense, dramatic character study, and its chief concern is not in terrifying you, but in putting you in the shoes of the odd, haunting 9-year-old boy of the title.

Ted lives in an off-highway motel in the middle of nowhere that his dad (David Morse) runs. They don’t have much business; each guest that comes through is something of an event in and of itself, and Ted spends most of his time scraping roadkill off the pavement for quarters and shifting around a nearby junkyard. His dad’s a lonely, sad guy, resigned to carrying out his days turning down beds and manning a desk for guests that never come, but Ted is even worse off; he misses his mom, who has apparently run off to sunny Florida, and he’s so starved for human contact that he doesn’t know how to interact with people when he finally gets a chance. One day, he decides to forcibly stimulate a little business by causing a car accident right in front of the motel, necessitating the driver to hunker down for the night. This driver (Rainn Wilson) seems to have some quirks of his own, and it’s not long before he and Ted create a tenuous, yet natural bond. But these people are all damaged, and it’s not long before Ted’s father becomes suspicious, leading to a chain of events that bring out the worst in everyone involved.

Morse and Wilson get the bulk of the dialogue, and achieve a level of quiet power that helps set the mood for the film. Wilson, in particular, is more in HESHER mode than he is like his legendary Dwight Schrute or the Crimson Bolt, and gets to play a number of tones as the mysterious, haunted traveler. But this is called THE BOY for a reason, and young Jared Breeze is in all but one scene in the film, and holds your attention for every minute of it. I can see a bunch of writers and directors having a particular idea of how this character should be depicted, and the tendency to play him as a Norman Bates or Damien Thorne-type must’ve been attractive to the filmmakers. Breeze and director Craig William Macneill do something way cooler; they let you develop a natural empathy for the character, as you relate to his sense of loneliness, desperation, and even playfulness. He’s a damaged kid, and engages in extremely questionable, sometimes horrifying behavior, but we don’t hate him or fear him for it. We only wish that his circumstances were such that he’d be aware, or have control, over what he did and how he related to people. Breeze is the center of the film, and somehow Macneill was able to cast and direct the young actor to an degree that any horror director of any age should aspire to emulate.

The tone is melancholic rather than menacing, and the drab, desert-y color palate creates an almost post-apocalyptic environment that fits the story. The absence of a prominent female character, or a bunch of side characters on general, makes the motel feel like a place forgotten by time, making Ted’s attempts at escaping his surrounds all the more immediate. Macneill and co-writer Clay McLeod Chapman pace the film very deliberately, dispersing information carefully and not always in chronological order. There’s a specific rhythm to this film that is, again, almost anti-horror, and the awkward messiness of the various scenes is allowed to sink in and fester. It was originally made as a short, and there are some story elements in the feature-length expansion that maybe aren’t crucial to the film, but often these scenes create a natural, laid-back feeling that helps create the idea of this place where there’s nothing to do except meander and dream of greener pastures.

It’s hard to make a serious, mature film through the eyes of a little kid, and it’s even harder to do that with this sparse dialogue and sparser environment, but Macneill, McLeod, and Breeze have pulled it off. A lot of us film geeks get where a film is going very early on in the narrative, but I was still trying to put the pieces together well into the film, all the while still being entranced by every tidbit of info or action that went down. THE BOY doesn’t reinvent the wheel or anything; later in the film, something develops that gives anyone with a cursory knowledge of horror films some idea of where things are going. But much like its protagonist, it is a unique little beast, and if you let the dark, broody tone suck you in, both the ride and the payoff should give you your 12 bucks worth.

BONE IN THE THROAT, dir. Graham Henman

Even though Anthony Bourdain’s novel, Bone in the Throat was published 20 years ago, it’s somehow appropriate that it didn’t get made into a movie until now. The foodie scene is bustling bigger than ever, particularly in England, where director Graham Henman has transplanted the story from Bourdain’s original Little Italy setting. It was only a matter of time before someone would make a thriller set in and around the kitchen of a high-class eatery, with an ambitious young chef as the lead. And who better to spin a tale about coke-addled cooks, crooked restauranteurs, and food-crazy gangsters than Anthony Bourdain?

Ed Westwick plays the lead, Will, who works as a line cook at FORK, a hot London sushi joint. His boss, Rupert (Rupert Graves, looking not unlike Bourdain himself with his slicked back grey hair) is deeply in debt to a gangster named Charlie, who regularly sends Will’s hoodlum uncle “Ronnie The Rug” (Andy Nyman) to skim a percentage of the profits off the restaurant. One night, Ronnie sees Rupert getting into the car of a detective (Steven Mackintosh), and deduces that he’s been serving as an informant as part of a long op to get to Charlie and his underling, Lewis (Neil Maskell). Ronnie and his muscle, Skinny, goes back that night and slits Rupert throat right in front of (or rather, right behind) the unwitting Will. Ronnie, happy to have Will in the fold of his criminal activities, cleans up the mess and kindly reminds his nephew to keep his mouth shut, lest he suffer the same fate. But the detective, Will’s girlfriend (who also happens to be Rupert’s daughter), and the mobsters are all watching the aspiring chef like a hawk, and the young lad has is forced to stay one step ahead of everyone involved in order to remain out of jail, or worse, a coffin.

Henman specifically mentioned after the film that, although he decided to move the story to his native London, he did not want the film to feel like Guy Ritchie’s cockney gangster films. Thankfully, he’s successful in depicting a rhythm, cadence, and environment that feel completely removed from SNATCH or LOCK, STOCK, AND TWO SMOKING BARRELS. These gangsters are both filthier and more refined than their Ritchie counterparts: Charlie and Lewis pose as straight businessmen (not like Wilkinson’s powerful kingpin in Ritchie’s ROCKNROLLA), and look down at the filthy, near-psychotic Ronnie. Nyman, as Ronnie, walks away with the movie in his pocket. Walking around with an unquenchable bloodlust, the horrible wig that earned him his namesake, and a fresh fish dangling out of his trenchcoat (his notorious taste for rank fish is well-known and oft-mocked), Ronnie the Rug comes off as both pathetic and extremely dangerous; not a combination you often get in these films.

The film opens with an abrasive montage of close-ups of people eating (a motif that continues through the whole film) set to a thrashing rock song, and proceeds to move at a steady clip, introducing its collection of characters quickly without shortchanging us of any key info. By mixing the world of London crime and gourmet cuisine, the film feels hip and modern, and the scenes in the fast-paced, highly competitive kitchen feel authentic and believable. As the plot machinations stack up, and Will starts having to figure his way out of his predicament, the energy of the film starts to deflate a bit; this is another one of those films where the protagonist is the least interesting character in his own movie, with his one interesting action (keeping the murder weapon as a sort of consolation prize) ending up pretty much ignored by the end. The third act has a couple of things that stretch the plot way past the point of believability. Without getting into specific, it’s one of those denouements where the lead knows exactly how certain characters will behave, down to the millisecond. It’s jarring and annoying enough to hurt the film as a whole, and sent me walking out a lot more miffed than I expected at the halfway point.

Even though the film opens far better than it closes, BONE IN THE THROAT is certainly no dud of a gangster flick. The dialogue is concise and often funny, the characters are archetypal but memorable, and the emphasis on food and restauranteurs gives it a very signature feeling. Every time a character takes a bite of food, there’s a close-up on their mouth, and most of the time you end up salivating over the courses on display. This is one of those BIG NIGHT, CHEF-type movies where you’ll really want to get a big meal afterwards (I was more than mildly irked that all the sushi places in Austin had already closed by the time we got out). Not the best British gangster film I’ve ever seen, but ample evidence that there’s plenty of room in the genre for fresh, original takes.