I don’t think Francis Ford Coppola gets a fair shake.

Yes, I know that THE GODFATHER ranks number two on both AFI and IMDB’s lists of the best regarded films of all time, and that it makes it to the number one spot on even more lists. I know that THE GODFATHER: PART II is the only sequel to a Best Picture winner to win Best Picture itself, and was the only sequel ever to land the award until LORD OF THE RINGS: RETURN OF THE KING back in ’03. I know that many have proclaimed his APOCALYPSE NOW as being the finest movie ever made about the war in Vietnam (“My film is not a movie, it’s not about Vietnam. It is Vietnam.”). And, to be sure, I know that he’s personally a six-time Academy Award winner, having most recently been honored with the Irving G. Thalberg award for his prolific career as a producer (via his production company, American Zoetrope).

So why don’t I think Coppola gets his proper due for his work?

Well, for one, I think that the critical and financial success of THE GODFATHER was quickly dominated by JAWS and, later, STAR WARS as the defining cinematic moment of the 1970s. Coppola was at the head of the pack of late-60s/early-70s filmmakers which included Peter Bogdanovich, Michael Cimino, William Friedkin, and Bob Rafelson, but when Spielberg and Lucas came in with their record-breaking blockbusters, all those guys, with their personal stories ladled with tragedy and ugliness, took a back seat. All of a sudden, the industry was watching the older crew fail, one-by-one, and Coppola’s ONE FROM THE HEART was as epic a failure as any of them (save for possibly Cimino) were forced to suffer through.

But more than that, I believe it’s because he was an anomaly in the American film industry a dude who was pulling in unheard-of-sized crowds with something resembling actual ART, rather than the spectacle-based star vehicles that defined the ‘50s and ‘60s. His movies were saying something, were impeccably crafted, and they were really successful…at least for a while. Someone of Coppola’s ambition, stature, and talent was always doomed to fail in this industry, and the crashes of his career were nearly catastrophic enough to overwhelm the hits. He was too big and too daring for his failures to be anything less than spectacular, and I’d argue that even when he doesn’t quite stick the landing, his results are never even remotely uninteresting or devoid of merit.

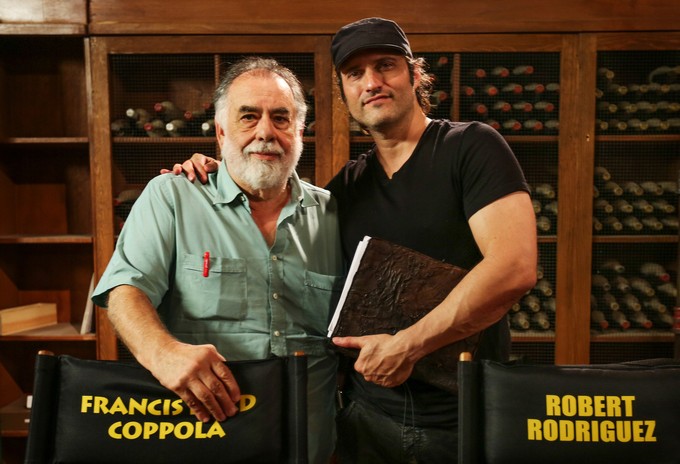

So it’s awesome to see that he’s the latest subject of Robert Rodriguez’ DIRECTOR’S CHAIR series for the El Rey Network. If you’ve never seen the show, it has Rodriguez sitting down with legendary filmmakers (the previous guests have been John Carpenter, Guillermo Del Toro, and his buddy Quentin Tarantino) and inquiring about their lives and the various cinematic classics that they’ve produced. It’s an hour-long show (meaning about 42 minutes in reality), so there’s no time to delve deep into the directors’ “lesser” works, but Rodriguez knows how to prod for the choice tidbits and fanboy trivia that gets us all excited about stuff like this.

Rodriguez sits in a wine cellar with Mr. Copplola at his Inglenook Winery in Napa Valley, and we see some stills of the director in his youth as well as footage of the Disney films that inspired him. He claims that, when he was attending Hofstra, he was in all the clubs, “like the kid from RUSHMORE, if you remember RUSHMORE.” (quick reminder: that kid from RUSHMORE was played by his nephew, Jason Schwartzman). At UCLA, his creative efforts so prolific that younger students at the nearby USC were seeking his tutelage. The most significant of these young talents: George Lucas, whom Coppola describes as “like a kid brother” to him. Apparently, Lucas’ came up with an idea to rig a truck with filmmaking equipment and drive around the country, filming on the go, and improvising the story; this idea became Coppola’s THE RAIN PEOPLE. The truck was dubbed Zoetrope Studios, and was the beginning of Coppola’s production company of the same name, which he quickly grounded on Folsom Street in San Francisco.

After this intro, Rodriguez gets into the meat of Coppola’s incredible filmography, starting with:

THE GODFATHER

”I didn’t want to do THE GODFATHER…I realized it’s kinda like being a prostitute, in terms of…even though you’re this prostitute and you have to perform this act that should only be done for love, you must look at the prospective client and say, ‘Well, he has nice hair, there’s a kindness to him…’”

When applying to film school, they inevitably ask you to talk about a film that inspired you and made you fall in love with cinema and the art of filmmaking. I always chose THE GODFATHER. Not just because it is one of my favorite films of all time, as well as being unmatched in my mind in terms of sheer craft and technical opulence. It is, but that’s less significant than the film’s place in pop culture. It’s a staple of the cultural lexicon, like Adventures of Huckleberry Finn or Norman Rockwell or Mickey Mouse. You can quote the movie freely, or call people you know the names of characters from the film, and, for the most part, folks will understand you’re talking about. It’s up there with GONE WITH THE WIND and Lucas’ own STAR WARS in terms of ubiquity, and I don’t know anyone who thinks that status is anything less than wholly deserved.

It’s not like there weren’t dramas about the tumultuous lives of well-to-do families before THE GODFATHER, and there certainly was no shortage of bloody gangster pictures. The genius of THE GODFATHER was the melding of the two: the high drama of the Corleone family saga mixed perfectly with the bloody murders and pulpy criminal behavior. It’s filled to the brim with all the elements people want from their movies, from romance to family tensions to violent shootouts to period settings to gorgeous, arch cinematography and, of course, terrific actors of both the old guard (Brando, Sterling Hayden, Richard Conte) and the ‘70s renaissance (Pacino, Caan, Keaton, Cazale).

It is well known that it was something of a for-hire gig for Coppola, and that the chair was originally offered to Sergio Leone (who refused in order to work on his own crime epic, ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA), and many of our favorite elements and moments were the result of on-the-fly improvisation. It seems that he was just as surprised by the impact of THE GODFATHER as anyone else, and he remembers his excitement when he first watched the climactic baptism montage with the organ music over it, when he realized he had something special. It really does lend to the notion that the film is one of the happy accidents of contemporary cinema, something that, in all likelihood, should never have existed, and which may never be replicated again.

THE CONVERSATION

”I wrote THE CONVERSATION in those days, at this time, absolutely nobody was interested in giving me the money to do it, and it wasn’t even a lot of money! So you always had this idea, ‘Well I’ll do that film, and I’ll make a lot of money on that film ‘cause it’ll be a regular film, and then I’ll take that lotta money and I’ll come back and I’ll make this film.”

Before I’d seen it, I’d hear people talk about THE CONVERSATION like it was that great, misunderstood masterpiece from a proven genius. Like someone saying, “Everybody loves Dark Side of the Moon, but you don’t know Pink Floyd until you’ve heard Animals.” THE CONVERSATION seemed like the “cool” Coppola ‘70s flick, like THX-1138 for Lucas or DUEL for Spielberg. So of course, I was a little surprised it was an intense, slow-burn thriller with a very reserved, middle-aged lead, but even more surprising was how palpably affected I was by it.

Now, I’m not going to go too deeply into how its story of a surveillance expert in over his head remains relevant to this day, but I will say that Coppola (with the assistance of sound svengali Walter Murch) creates a tangible sense of what it would be like to be watched all the time about 40 years before that would become a pervasive factor of modern society. The writer/producer/director does a killer job of using his cinematic trickery to put you in the shoes of Gene Hackman’s Harry Caul as he falls deeper and deeper into the rabbit hole of paranoia. It’s got one of those rough, ambiguous ‘70s endings, and it does you few favors in terms of dispersing the plot in a clear, obvious way, but it’s all told with such a confident restraint and professionalism that it sucks you right in. Caul is an inscrutable codge, who even his co-workers have a hard time hanging around, yet through Hackman’s subtle performance and Coppola’s direction, we feel every tinge of his increasing fear as he finds out just how dangerous his recordings are.

THE CONVERSATION was nominated right alongside Coppola’s other ’74 masterpiece, THE GODFATHER: PART II, for a Best Picture Oscar, as well as winning the Palm d’Or at Cannes, but unfortunately THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR doesn’t spend much time on what the film meant to the director, or even how prophetic it’s subject matter was. So if you don’t know why THE CONVERSATION is so great, this episode ain’t gonna do it for you: you gotta go check it out for yourself.

THE GODFATHER: PART II

Another allegedly “for-hire” gig for Coppola (this one so he could make THE CONVERSATION), another undisputed masterpiece.

This and TERMINATOR 2 are the cliche examples for sequels that didn’t piss on the legacy of the original, but unlike Cameron’s bigger-badder follow-up, GODFATHER: PART II is a completely different monkey than it’s predecessor. It’s novelistic approach of following two parallel plotlines, one telling Vito’s story and the other Michael’s, is the thing that either distances you from the film or is it’s badge of distinction among the rest of Coppola’s filmography.

If the Corleone saga is the story of the American Dream, then PART II is the one that tells the story about America itself, from the influx of immigrants into Ellis Island at the turn of the century to the mob infiltration of Nevada in the ‘50s. We see the idealism of Vito Corleone’s pragmatic family man give way to the cutthroat viciousness and paranoia of Michael’s reign as boss, and watch as the hope of those first steps towards prosperity is slowly whittled away by fate, betrayal, and most uncompromisingly, time. It’s just Michael and Connie in the end, with only a flashback scene to remind us at how much life the Corleone household once contained. This one doesn’t have the cuteness of Luca Brasi or “Take the gun, leave the cannolis,” nor the sweeping romance of Michael’s exile to Italy (though the Corleone sequences are stunning in their sun-baked homeyness). It’s both brutal and beautiful, and complements the original film without once feeling like a cash-in or a money grab.

Coppola tells Rodriguez that his original plan was only to work on the script for PART II and to help Paramount find a new director. His choice: a young upstart by the name of Martin Scorsese. The studio balked, and agreed to Coppola’s terms to return as director (including barring former studio head Robert Evans from the set). He originally blew it off as a “one for them,” but he used the opportunity to work out an idea for a story involving a father and son at the same point in their respective lives, and thus set the standard for every sequel that’s come since.

I have to think that his begrudging approach to making both GODFATHERs is intrinsic to how successful and well-received they were. Perhaps it was the perfect combination of overthinking and underthinking, of planning and improvisation, of “wouldn’t it be great if…” and “oh fuck it, let’s shoot it!.” Whatever it was, it was a one-two (or one-two-three, if you count THE CONVERSATION) punch up there with any in ‘70s American filmmaking, and one thing was for sure: whatever this guy had up his sleeve for his next film was going to be something worth looking out for…

APOCALYPSE NOW

”I said, ‘I’ll make it like THE GUNS OF NAVARONE, some big movie, and I’ll make all this money with the big studio war film and I’ll make little art films.’ Then APOCALYPSE turned out to be this ridiculously big art film…worse, one that had become so strange that I didn’t know how to end it.”

There are a ton of movies about Vietnam, but only a couple struck a chord with the American consciousness, and I’d argue none as successfully as APOCALYPSE NOW. There’s something to be said for the hellish brutality of films like CASUALTIES OF WAR and JACOB’S LADDER, or the tragic loss of innocence of THE DEER HUNTER and PLATOON, and even the cold cynicism of FULL METAL JACKET. But the insanity…nothing ever showed just how fucking mad the war must’ve been, or the madness it brought out in the boys and soldiers that went over there, like APOCALYPSE NOW.

There’s Looney Tunes all over this picture. The surf-obsessed Kilgore, and his acid-popping idol Lance. The increasingly unhinged Chef. The desperate attempts at control by Chief. The central mission itself, a covert assassination of the most effective general in the whole war. Even the lead, Martin Sheen’s Captain Willard, enters the film attempting to drink and air-fu out his frustrations as he sweats away in a Saigon hotel room. And of course, there’s Kurtz, all-powerful, sitting in the darkness, spouting off his seemingly crystal-clear ruminations on the nature of war while taunting his prospective assassin to finish him off.

To get a real glimpse of how close to the edge this film drove Coppola, you have to check out the 1991 documentary HEARTS OF DARKNESS. You hear the crippling fear and uncertainty in the director’s voice as he tells his wife (in unknowingly recorded conversations) about how he’s wasting all his money and sending his production off the rails. But, as he tells Rodriguez in THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR, he went on “the journey,” and came up with something that is both unlike anything that came before it and that is wholly, undeniably his.

And if you haven’t seen it on the big screen, do so the next time the chance comes along. It is one of cinema’s truly BIG films.

ONE FROM THE HEART

”I really intended to do it live, and I chickened out at the last moment.”

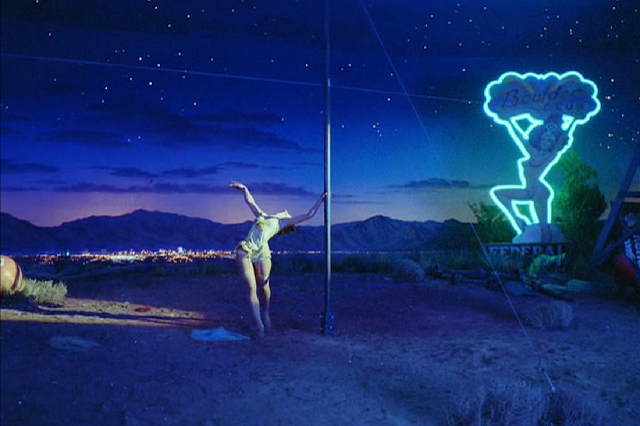

ONE FROM THE HEART is known more for its sinking of American Zoetrope as it is for anything about it as an actual movie. It really is a shame that the musical-romance about an estranged married couple in Las Vegas ended up costing as much as it did, which was mostly due to the decisions to build Sin City on a set and to implement a patented early form of the now-standard “video village.” It’s a visually extravagant, yet simple little tale, and it has an infectious, lively energy in its best moments. It’s got a cast headed up by Teri Garr, Frederic Forrest, Raul Julia, and Natassja Kinski, and a lovely score by Tom Waits. It’s no disaster, by any means, but THE GODFATHER it ain’t, and it lost so much money for Coppola that he spent the next decade-and-a-half working in the salt mines of for-hire studio filmmaking to pay off his debts.

Still, it’s another prime example of Coppola going for it, and attempting to do something that could only come from his own wild imagination. It’s just the one that caused the most damage.

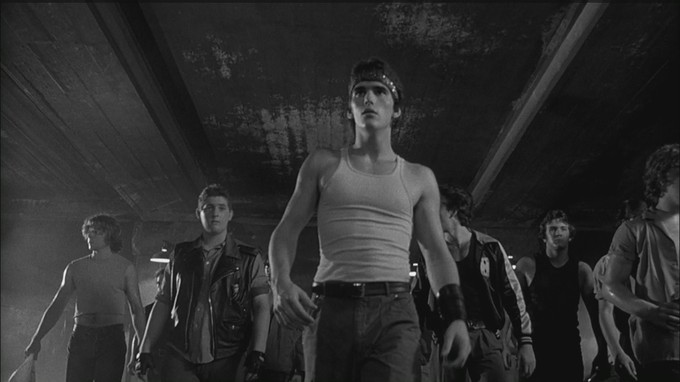

THE OUTSIDERS

”The idea of THE OUTSIDERS, the concept was that the boys in THE OUTSIDERS were all reading GONE WITH THE WIND, and they loved GONE WITH THE WIND. So I said, ‘I’ll make it a little like GONE WITH THE WIND.’ But then it started to look too saccharine to me, and the music was schmaltzy, and I started to worry about it.”

I somehow got through elementary/middle school without reading THE OUTSIDERS, but in my school, I was the exception to the rule. I knew a ton of people who had read S.E. Hinton’s book, but none could tell me squat about that movie that boasted one of the star-studdest covers in all of Blockbuster.

We’re talking Matt Dillon, Ralph Macchio, Patrick Swayze, Emilio Estevez, Rob Lowe, and Tom Freakin’ Cruise. And SOUL MAN.

Even Coppola admits the flick’s a little “saccharine,” but it recalls the “angry young man” melodramas of the ‘50s, and there’s a certain infectious sincerity to the bro-ing out between the lead characters. All the future stars get something to do, especially in the “Complete Novel” director’s cut, and Coppola paints the Y.A. story with a level of nostalgia that adds color to the posturing and teen angst. I always liked the film despite it’s sometimes overwhelming corniness, and I give Coppola credit for casting and shooting the film in such a way that it is visually striking and never boring.

Still, as far as Coppola-directed Hinton adaptations, THE OUTSIDERS was about to have its ass kicked by the filmmaker’s next…

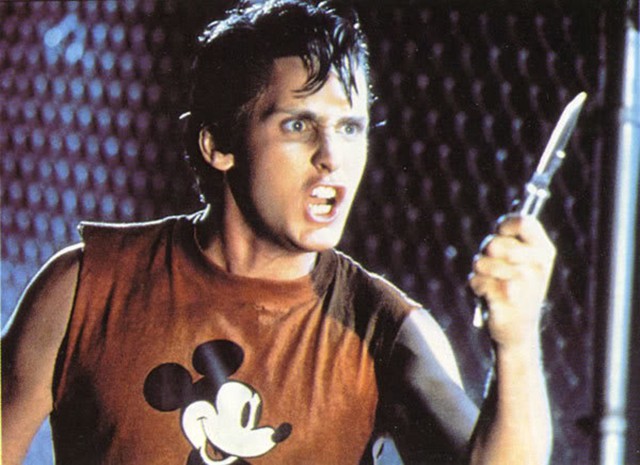

RUMBLE FISH

”I was noodling through this Rumble FIsh book, and it struck me, ‘This could be black-and-white!’”

I wouldn’t say RUMBLE FISH is the “best” movie in Coppola’s filmography, but I’ll be damned if it isn’t the coolest.

From the score by The Police drummer Stewart Copeland to the gorgeous black-and-white photography to one of the best Mickey Rourke tough guy performances amidst a career of tough guy performances, everything in this flick is just plain bad (in the immortal words of Run DMC, “Not bad meaning bad, but bad meaning good”). Coppola’s “art film for kids” uses experimental photography, vague storytelling, and an existentialist bent to depict the relationship between Matt Dillon’s Rusty James and his older brother, the immortal “Motorcycle Boy” (Rourke).

Its cast may even be a contender against THE OUTSIDERS’: Dillon, Rourke, Diane Lane, Nicolas Cage, Laurence Fishburne, Dennis Hopper, Chris Penn, Tom Waits, and a tiny, spunky Sofia Coppola.

It’s a brisk 94 minutes, shorter than everything Coppola has done aside from DEMENTIA 13 and TWIXT, and it has a poppy, beat-era energy that is unique among his directing output. It’s sad, but not sappy, stylized but not self-conscious, low-key but not boring. I don’t know if it’s for kids, as Coppola had intended, but it’s definitely an underrated entry in Coppola’s filmography, and a unique look at what it’s like to be an angry young man.

And did I mention that Mickey Rourke is just all sorts of cool in it?

BRAM STOKER’S DRACULA

”The story of Dracula was written at the same time that the cinema was invented, so I thought, ‘What if they made the story of Dracula as if we were making it with the technology of the turn of the century?’”

This was the first Coppola film I was actually aware of as a child, due to the omnipresent and striking promotional art, and I was always intrigued by the little bits I’d catch here and there. But while I like the look of the film, and the baroque intensity with which Coppola tells the tale of the most famous vampire of western lore, I find the film somewhat hollow. Coppola doesn’t seem too concerned with any of his characters, Dracula included, but rather on creating the sort of grand spectacle his old boss Roger Corman would never dare to spring for. There’s literally geysers of blood in this thing (an element which was well-spoofed in Mel Brooks’ DRACULA: DEAD AND LOVING IT), and the in-camera effects by Coppola’s son, Roman, remain breathtaking to this day.

But man, with this cast, I’d like a little more character. Keanu’s blandness and shitty accent are stuff of legend, but everyone else is pitch-perfect on paper: Winona Ryder, Richard E. Grant, Sadie Frost, Billy Campbell, Monica Bellucci, and Gary Oldman as the titular bloodsucker. Everyone does servicable work, and some even get solo moments to shine, but they’re washed away by the grandiose nature of the production, leaving camera tricks and Michael Ballhaus’ compositions to provide personality. Only Tom Waits and a post-Hannibal Lecter Anthony Hopkins jump off the screen as Renfield and Van Helsing, respectively.

Add to that a perfunctory action-movie climax which never quite sat well with me, and you have a flick that, while being one of Coppola’s more lucrative latter-day works, feels more like the studio gig that it is than an inspired take on the classic monster. Stylish, yes, but a case of “style over substance” to me. Definitely fun to watch though.

The DIRECTOR’S CHAIR episode closes with a few thoughts from Coppola (including the badass reveal that there’s a 4K Blu-ray coming for a director’s cut of THE COTTON CLUB). While I would’ve liked more extensive discussion about THE CONVERSATION, THE COTTON CLUB, THE RAINMAKER, or any of Coppola’s recent independent work, I can understand that there’s only so much you can fit into a 42-minute program. It’s not like they’re going to allot time for his thoughts on SUPERNOVA.

Rodriguez defines Coppola by his technical savvy, his affinity for both family and food, and his unwillingness to play along with the studio system, and all are crucial aspects of what makes Coppola’s career stand apart from the rest. I also give him credit for doing what most commercial filmmakers only dream of: creating something artful and special that can also connect with people on a mass scale.

” When you give yourself totally into making a film, the film is also sort of making you.”

THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR with Francis Ford Coppola airs tonight at 8PM ET/8:30 PT on the El Rey network.