By Jeremy Smith

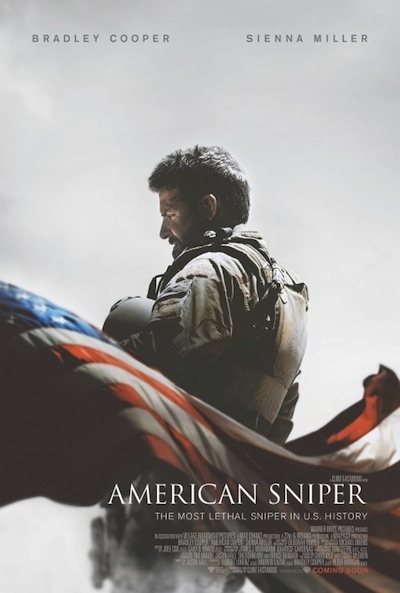

Clint Eastwood's AMERICAN SNIPER is a portrait of a great killer named Chris Kyle. There was also a real Chris Kyle: Eastwood's film is based on the bestselling autobiography of the former Navy SEAL who racked up 160 confirmed kills over ten years of vigorous service in the United States Navy. But let's leave real life out of this. Real life is messy and contradictory and, in Eastwood's film, largely left to the periphery. AMERICAN SNIPER, as written by Jason Hall, is simply a close-quarters study of a man blessed with skill, certainty and an unswerving devotion to his country; this clarity is crucial to understanding Kyle's deadly efficacy, and the film's oft-rousing depiction of warfare.

The film opens with a jarring aural juxtaposition: a Muslim call to prayer wafts over the Warner Bros logo, but is quickly drowned out by the rubble-crunching tread of a tank. These sounds ominously hang over a bombed-out Fallujah neighborhood, where a company of U.S. soldiers methodically hunt for insurgents. They're boxed in, exposed, but far from defenseless thanks to the sharp-eyed "Legend" perched on a nearby rooftop. This is Chris Kyle in his natural habitat, taking a god's-eye view of the world through his rifle scope; should someone stray into his line of sight, their life is officially, unwittingly on the clock. One false move, and pop goes the noggin - regardless of age or gender.

This is the initial conundrum faced by Kyle: does he have enough visual information to take down an Iraqi woman and her young son, both of whom appear to be approaching his fellow soldiers with a bomb? It's a split-second call, but one that comes naturally to Kyle. You see, he's always been right. About everything. Just before he pulls the trigger on the boy, Eastwood flashes back to Kyle's childhood, where he learned two important lessons: he has a gift for shooting, and, metaphorically speaking, he is a sheepdog. Both of these realizations are drilled into Kyle by his father, who informs him that the the world is made up of three kinds of animals: wolves, sheep and sheepdogs. The Sheepdog, says the elder Kyle, walks the hero's path; he protects the sheep from the amoral wolves. "We protect our own." Cut to a shot of adult Kyle donning a white cowboy hat. Coming from a director who owes his career to westerns, it's a stirring moment presented with zero irony; Kyle, at least in his own mind, is the hero. Does Eastwood agree?

When you lead with an image as on-the-nose as a white cowboy hat, you've loaded every subsequent composition with potential meaning. Visually speaking, Eastwood is addressing the audience with a basic cinematic vocabulary, but, as we've seen in masterpieces like UNFORGIVEN and A PERFECT WORLD, no one possesses a defter touch when it comes to subverting the accepted definition of these tropes. So you pay close attention not just to Kyle's behavior throughout the film, but his attire and accoutrement. When, in battle, he opts for a beige ball cap worn backwards, does this shading suggest the creeping onset of doubt? Or when he sports a tattoo of a Jerusalem cross, does this mean he's committed himself to a literal Holy War? What's going on in this guy's head?

Eastwood is so dialed-in visually (in terms of craft, this is his best movie since A PERFECT WORLD), you scan every frame for insight into Kyle's character - and, perhaps, the filmmaker's feelings about his subject. But there is no depth to Kyle. He is a true believer - an ideal soldier who doesn't question the wisdom of the mission. When he sees the Twin Towers collapse on television, the sheepdog springs to action; he's off to war, and he instantly makes his mark as one of the finest killers wearing the stars and stripes. What to make of this? In the film's narrow, largely apolitical view of the Iraq War, I see it as a born warrior doing precisely what his country has called him to do - and, in this bubble, every action Kyle performs on Eastwood's battlefield is just and heroic. This is the guy you want protecting your country (they call him "The Legend"*; we need Chris Kyles. He's also the last guy you'd probably want as a husband - if only because his first duty is to his country, not his family (though Kyle's defense of his country is certainly an extension of his desire to protect his kin).

The most troubling scene in AMERICAN SNIPER finds Kyle being confronted at a garage by a retired Marine. The former soldier thanks Kyle for saving his life, and shows his battle-tested bona fides by lifting up his pant leg to reveal a prosthetic leg. Kyle can barely make eye contact with the man, which, given that we've spent the entire movie at his point of view, makes us almost resent the wounded veteran. When the man squats down to regale Kyle's son about his father's heroism, we just want him to go away. Can't he see that Kyle wants no part of his adulation? It was a thing he did, and now it's done, and let's move on with our lives. In a later scene, Kyle hangs out with disabled veterans at a shooting range. Upon registering a killshot, one of the men boasts to Kyle "Who's the 'Legend' now?" Kyle just stares off into the distance. "That's a title you don't want." Given the way he's been portrayed for most of the film, this plays as false modesty, not regret.

Some critics have complained that we walk away from AMERICAN SNIPER knowing little about Chris Kyle; I'd argue that the little we get is all there is to know. And I'm just talking about the onscreen character. The film's biggest misstep is closing with real-life footage of Kyle's memorial, which unfortunately requires the viewer to link the big-screen Kyle to the guy who allegedly lied about killing looters in the chaotic aftermath of Hurricane Katrina. For a film that's spent two-plus hours avoiding personal judgment or much in the way of political context, it seems wrong to suddenly celebrate the man's life in full. Because this hasn't been considered - at least not in a warts-and-all fashion. And this is a huge problem because, despite the apparent psychic pain incurred over his ten-year combat career, Kyle is presented as an infallible killer. He never questioned his country's reasons for going to war, and we never question his actions on the battlefield. If you know nothing of Kyle aside from what you've learned from the movie, you walk out with a profound respect for a perfect, morally-calibrated killing machine. In that sense, Kyle isn't simply a great warrior or the good guy. He's God.

*A pretty clear reference to THE MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, but Eastwood and Hall do nothing with the idea.