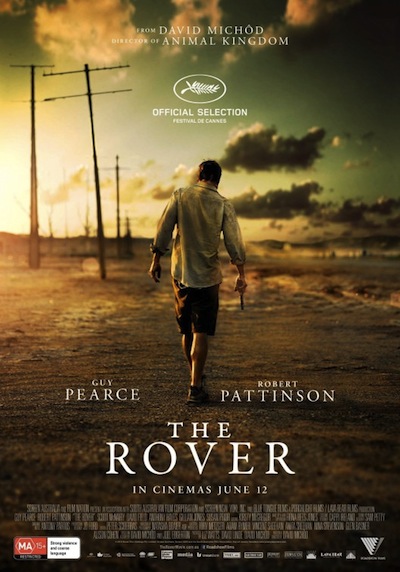

David Michôd's THE ROVER may center on one man's relentless search for a stolen car in a nearly lawless Australian outback, but this is no MAD MAX homage. Aside from one nifty car wreck at the film's outset, Michôd spins a lean-and-very-mean yarn in which survivors of a global economic collapse are at each other's throats for table scraps. Guy Pearce plays Eric, the man looking for the car, while Robert Pattinson uglies himself up as Rey, a slow-witted kid left for dead by his outlaw brother Henry (Scoot McNairy). Though Eric gets Rey patched up, he's not at all concerned for the young man's well being going forward; he just wants Rey to lead him to Henry, who has in his possession the only thing in the world Eric still cares about.

While Michôd previously evinced a flair for bleakness with 2010's ANIMAL KINGDOM, that film at least had a live-wire lunatic in Ben Mendelsohn and a chillingly malevolent Jacki Weaver. THE ROVER is a stripped-down, sunburned piece of nihilism that gets in your bones; Pattinson does add some color and heart to the proceedings, but this is only because Rey isn't savvy enough to know he's doomed. This is an unremittingly grim depiction of humanity slowly circling the drain; the damage has been done, and Michôd's characters - whether they care to admit it or not - are just scurrying about in the oppressive heat of the outback looking for a place to slip away.

This may sound like quite a wallow, but Michôd skillfully frames THE ROVER as a rumination on what's been lost. There's a magnificent scene late in the film where Rey listens to Keri Hilson's "Pretty Girl Rock", and the unfettered joy of the track is at once exhilarating and cruel; after an hour's worth of violence and despair, the world-exploding possibility of a great pop song couldn't be more out of place. And it packs a wallop because Michôd fully commits to the utter hopelessness of the post-collapse throughout.

Michôd had just completed the 2014 Cannes Film Festival gauntlet when I interviewed him a couple of weeks ago in Los Angeles. He was still trying to get a handle on how the film plays for an audience, and wasn't entirely sure the Cannes crowd was the most accurate barometer. I can see why the film didn't wow at a festival; critics, if they're doing their job, are seeing between three and five movies a day, and more understated movies have a tendency to get lost in the shuffle. Save for the aforementioned scene, THE ROVER is not a film that pulverizes; it's a quietly unnerving experience that stays with you long after Pearce reaches the somber end of his journey.

Jeremy: Initially, just given the premise that it's Guy Pearce looking for his stolen car in a post-Collapse Australian outback, I expected something along the lines of a Mad Max movie. This movie is not that. But it's hard not to have those movies in mind. In writing the film, were you thinking about subverting those expectations?

David Michôd: It wasn't necessarily about subverting people's expectations. It was more about me wanting to fulfill my own needs and desires. Initially, when Joel Edgerton and I first started talking about this movie, we thought we were writing a car chase movie for his brother Nash [Edgerton] to direct. I went away and started writing the screenplay, and immediately started writing the kind of movie I'd like to make, which isn't a movie full of car chases. In part, it's because I knew I didn't want to shoot a movie full of car chases because they're gigantic technical exercises; they're not necessarily fun to shoot, at least not for me anyway. But I also realized that I didn't really want to watch them, and the point of making a movie for me is to make something I'd like to watch. For me, the truly exhilarating stuff is actors in a room bringing interesting characters to life.

But now that you mention it, I was vaguely aware that if you put cars in the desert in the future, people are going to immediately think of MAD MAX on some level. But that was only a faint noise in the background for me. I never set out to make an action film - and didn't. But I did want to make something that felt menacing and frightening, but hopefully moving as well.

Jeremy: You say you don't like shooting car chases. Is that because you have to cede a certain amount of control as a director to your second unit when you do them?

Michôd: In this one, there's basically one car chase in the movie. Nash Edgerton and I quite carefully pre-visualized it before we started shooting. It was a car chase with a clear narrative of its own. By the time we'd finished the first day of shooting the car chase - setting up different shots, but playing the whole chase out every time - everyone on the film knew the story of the car chase. So it became quite easy for [Director of Photography] Natasha Braier and I to go to the second unit and tell them what we knew we specifically needed, but then also giving them license. "You've got a technocrane and a stabilized head, go nuts with it and see what you get!" They fooled around and they got a whole lot of stuff that was hilariously FAST & THE FURIOUS, and they knew that we probably weren't going to use it. But they had the gear, so why not give it a try? We pieced together the cut the way we knew we needed it, and the second unit was just icing on the cake.

When I say that, for me, the exhilarating thing about making a movie is about having actors in a room bringing interesting characters to life… you can have interesting characters inside these cars while a chase of this nature is happening, but my engagement with [the actors] is now completely retarded. I'm directing them by screaming at them through a walkie talkie, which is challenging. It's challenging for me and it's challenging for them, too. You can see it on their faces in the dailies. They'll be in the car acting their little hearts out, and then my ridiculous voice will come crackling through a walkie talkie, and you can see their faces scrunch into this look of "What the fuck did he just say?" It's not a way to elicit great performances from actors.

Jeremy: You talk about conveying menace, which really comes through when you juxtapose these disheveled characters against this vast, unforgiving landscape in a widescreen frame. As far as I'm concerned, having grown up watching John Carpenter movies, there's no better way to convey menace than to let things play out in a single widescreen shot.

Michôd: Unlike ANIMAL KINGDOM, which was a densely populated world in a very urban environment, I wanted to do something that was kind of the opposite here, which is an intensely intimate story between a small number of characters in a really vast and epic landscape. Whenever you have the opportunity to present the infinite expanse of that world around the characters, it's great to take it. Obviously, widescreen lends itself to that. And, to a certain extent, that landscape is so profoundly awe-inspiring that it would almost be a travesty to not shoot it widescreen.

Jeremy: How do your actors respond to having all this space in which to play?

Michôd: I think they like it. I think film and television actors especially can get frustrated by the piecemeal way that films and shows get made. You're constantly having to do little bits and pieces of things with interminable periods of waiting in between. When they're given the opportunity to sink into a nice, long dramatic dialogue scene, it's then that they feel they're really acting - even though, for me, those little bits and pieces of transitional material or whatever are as important as anything else, and they require your full focus and attention. It's in those deliberate and long dialogue scenes that the actors come most alive, and they can then carry those feelings into the bits and pieces. But like I was saying before, the thrill is watching those moments. When you start shooting a dialogue scene of that nature, watching it go through the first block-through to how it feels on take fifteen of a close-up is kind of miraculous. Especially when you don't have the luxury of long rehearsal periods in preproduction, you're rehearsing while you shoot and you need time and patience. But I find it exhilarating.

Jeremy: How is directing Guy different from directing Robert? Did they require different kinds of direction?

Michôd: I know that actors always have different ways of working, and that, in some ways, it's my responsibility to identify those different ways and adjust my direction to suit those different ways, but it never ends up working out that way for me. For me, it's always about gathering around you the actors with whom you will make this thing, and you'll become so familiar with each other that you're all talking the same language. Both Guy and Rob are just really good actors, and that's exhilarating for me.

One of the things I love about working with Guy is that he's so good at working in minute detail that by the time you get to that fifteenth take of a close-up in a scene, you have built a performance that might have somewhere in the vicinity of 200 minor adjustments in it that, together, you have built and crafted really carefully. With Guy, I feel the freedom to be directorially loose with him. Quite often, you read textbooks on how to direct actors, and they're full of the need for clarity and simplicity and transitive verbs and playable actions - all of which is true. That is a base principle to aim for. But the beauty of directing Guy is that he allows me to be looser than that. In between takes, we'll have a conversation about what we feel about the take that just happened, and it'll be loose and kind of about life, and I'll see him listening and see the gears turning and see him turning what we have just discussed into something that is playable - which is what all actors do, I think. You can give them the simplest transitive verb in the world, but they still have to turn that into something they can play. Guy is a master, but I find it to be true of all actors in a way. It can take a little bit longer with some actors to get there, but if you've got the time and you've cast the movie right, you'll always get there.

Jeremy: It's hard not to notice the presence of flies in this movie. They are everywhere. Is there any wrangling required, or do they sort of come with the location? It looks incredibly hot and brutal.

Michôd: It was. You don't wrangle the flies, you just learn to live with them. A seriously challenging movie to make out there would be one with no flies in it. You just learn to accept them, and you become comfortable with the fact that your right arm becomes a loose windscreen wiper that's constantly waving in front of your face. But we shot the movie at the toughest time of year, and we wanted to do that because we wanted all of that discomfort to land on the screen. If we'd shot the movie in winter, it would've been an entirely different movie. That part of the world just feels different. You've got these actors who are having to put on these costumes in 113-degree heat, and it inevitably bleeds into their performances.

Jeremy: This film takes place ten years after "the collapse". In writing the story and crafting the characters, did you make up a more detailed backstory about what brought these people to this place?

Michôd: It's not explicitly laid out in the film, but it felt quite specific to me. In some ways, the world in the movie is a product of me funneling my anger at the state of the world as it exists today and what I imagine it could be in a few decades' time. A particularly catastrophic Western economic collapse coupled with continued flagrant disregard for the very primary things that sustain us: the air that we breathe and the water we drink. In a way, I started realizing that this world I was imagining is a world that already exists in certain corners of the globe. This was just a kind of economic/geopolitical inversion in which Australia has become like West Africa or Afghanistan, and it was always really important to me that it exists this way. I knew I didn't want there to be one almost inconceivable cataclysmic event that would allow people to remove themselves from the fact that the world of this movie is not only plausible, but is kind of already happening all around us. You even get the sense in America that if you had the confluence of a couple of really bad events - like a Katrina and a budget crisis and a really struggling, massive underclass living below the poverty line - it wouldn't take much for all hell to break loose. So for me, the world of the movie was always quite specific, but I just didn't want to get bogged down in the exposition of it. But I'm finding that a lot of the conversations I'm having are about me trying to explain that this isn't a post-apocalypse; it wasn't an asteroid that destroyed everything and reduced us to cannibals.

Jeremy: It's just a term for us to lazily fall back on. I caught myself saying it to you earlier.

Michôd: (Laughs) Everyone does it.

Jeremy: When we talked earlier, you said that you'd read other people's screenplays as possible directing assignments, but you'd really prefer to direct your own material. Do you think you'll be a writer-director for the long haul?

Michôd: Yes. Having said that, I just finished shooting the first episode of a TV show set in the world of a New York ballet company that I didn't write. That's one of the things that I enjoy about TV: I can keep my on-set muscles flexed without having to bear the full responsibility of a thing that I built from the ground up. But I know that the movies, because they take such a temporal and emotional toll on me, I just have to love them completely. They have to feel like my babies that I have a parental responsibility to protect. No matter how ugly or deformed they are, they're mine. I want to feel that love for them, and I feel like that love can only come from me having inseminated the egg of the idea. (Laughs)

Jeremy: I like how you say directing television is a good way to keep the on-set muscles toned. It's a way of keeping creatively limber, isn't it?

Michôd: It feels really important to me. I realized that after ANIMAL KINGDOM, it felt like there were a couple of years of promoting the movie and a couple of years of figuring out what to do next. Then I did an episode of ENLIGHTENED, and suddenly realized that I hadn't been on set in three years. I remember thinking, "I cannot let this happen again." It's a fun thing to do. But the movies have to be mine, otherwise they will destroy me.

THE ROVER is currently in theaters nationwide. Do not miss it.

Faithfully submitted,

Jeremy Smith