Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

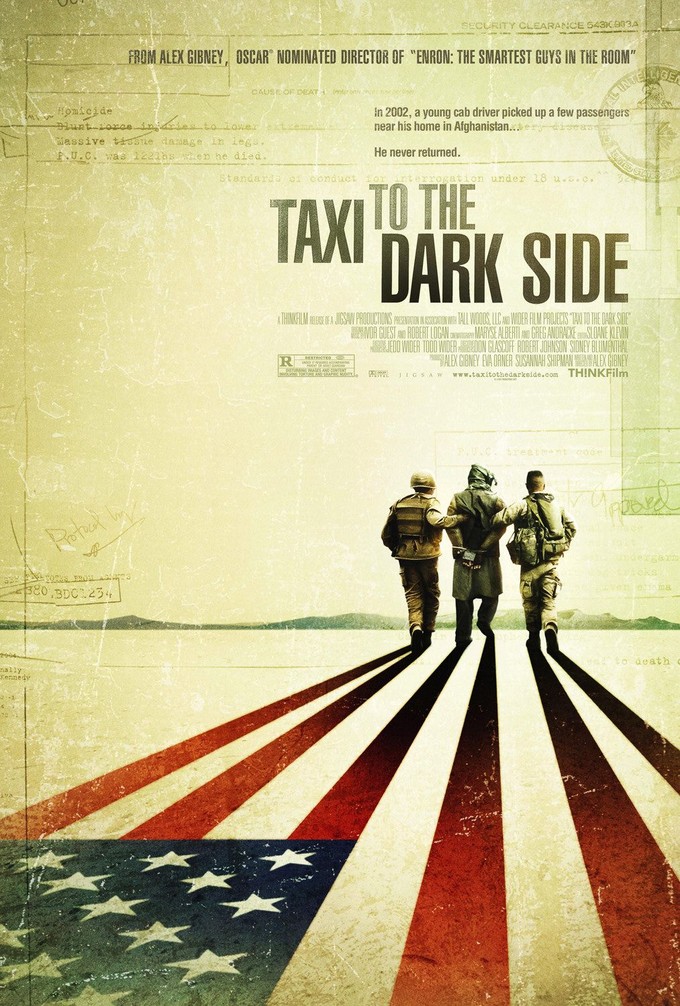

This column will tackle an Oscar winner from each year starting with the inception of the Academy Awards in 1929. My goal is to highlight lesser-known films from throughout cinema history that were able pull down one (or more) of the Golden Statuettes that remain such an integral part of Hollywood lore. I will also take a close look at the actual element(s) that the film was given awards for, with my analysis on how they hold up with years (or decades) of cinematic history in the rearview since. This week, I tackled Alex Gibney's 2008 winner for Best Documentary Feature, TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE. Come back next Sunday, true believers, for my look at the 1935 winner for "Best Story," W.S. Van Dyke's MANHATTAN MELODRAMA.

Now that movies like ZERO DARK THIRTY and LONE SURVIVOR are widely approved by both U.S. audiences and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, it's interesting to think about how our military conflicts in the Middle East were considered unfilmable just a few years back. Flicks like UNITED 93, GREEN ZONE, RENDITION, and IN THE VALLEY OF ELAH would come, and go, with little-or-no Academy recognition, and even less box-office success. SYRIANA was the first fictional film to deal with our military presence in the Middle East (even tangentially) to win an Academy Award, and that was almost five years after 9/11, and three full years after we had invaded Iraq (not to mention, the award was for George Clooney's acting). At the '07 awards, only one narrative film about the then-current wars, Iraq and Afghanistan, was nominated, and IN THE VALLEY OF ELAH was given just one nod, for Tommy Lee Jones' leading performance.

On the documentary side though, things were different. Errol Morris' THE FOG OF WAR beat the popular and influential CAPTURING THE FRIEDMANS for Best Documentary within a year of our second military engagement with Iraq. Two lesser-known Iraq-centric films, James Longley's IRAQ IN FRAGMENTS and Laura Poitras' MY COUNTRY, MY COUNTRY, were both contenders for the Oscar the same year JESUS CAMP, DELIVER US FROM EVIL, and AN INCONVENIENT TRUTH were up for the award (which the heavily-campaigned AN INCONVENIENT TRUTH won). And that same year IN THE VALLEY OF ELAH was recognized with a single nomination, three of the five nominated documentaries were specifically concerned with "Operation Iraqi Freedom" and the War on Terror. The winner was Alex Gibney's follow-up to ENRON: THE SMARTEST GUYS IN THE ROOM, TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE.

So while most of America (including the film industry) was averting their gaze from Hollywood's attempts to synthesize our international tensions into mass entertainment, the Academy saw fit to recognize TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE for its unflinching, often-grueling look at the military prisons that house suspected insurgents and potential terrorists. What was it about Gibney's documentary that allowed voters to mentally and emotionally engage with our armed conflicts in a way that more palatable, less severe narrative films had failed to do?

In a word: reality.

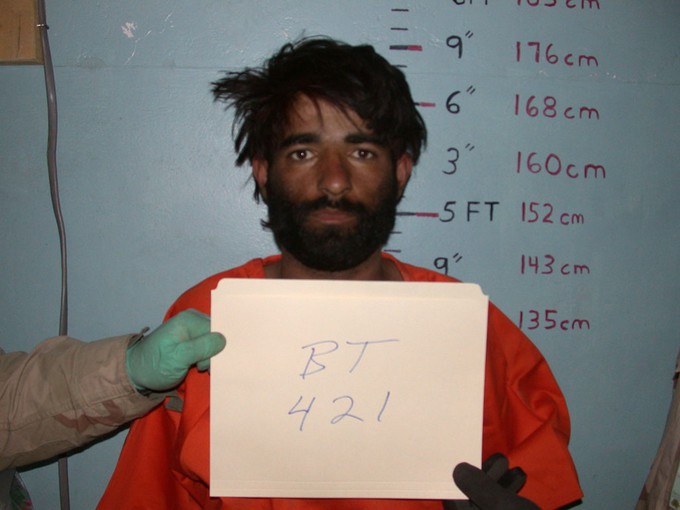

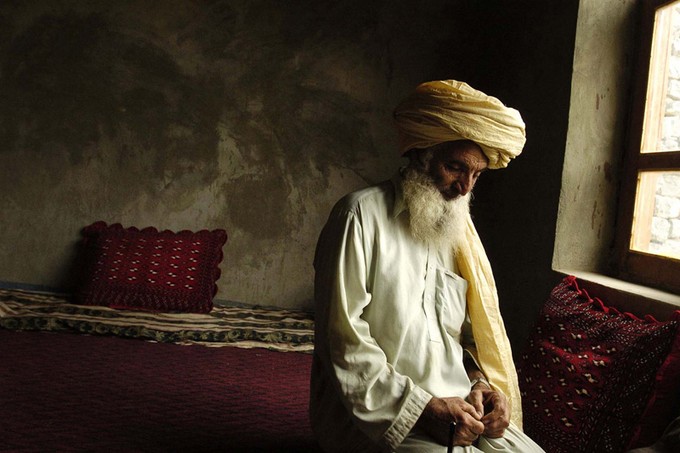

TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE uses the story of Dilawar, a young Afghani taxi driver wrongfully imprisoned on suspicions of terrorism, as a means of examining prison conditions for alleged enemies of the U.S. at the height of post-9/11 paranoia. Dilawar was detained in the summer of 2002 after driving three men suspected of attacking the nearby Camp Salerno back to his home village of Yakubi. Without any real connection to the suspects in question, and with no evidence of any sort linking him with Al-Qaeda or any terrorist groups, the Army imprisoned Dilawar for the last half-year of his life. On December 5th, 2002, Dilawar was interned at the Bagram Collection Point, a military prison; five days later, he was dead, after abuse to his legs became so intense that it caused his heart to seize.

We get face time with a lot of the Army personnel who dealt with Dilawar in the last few days of his life, many of whom stood trial for allegations of abuse, misconduct, and straight-up torture. Sure enough, they all admit to their role in Dilawar's abuse, but whether it's deflection of blame or their honest recollection of events, they claim that their treatment methods were directly sanctioned by their superiors at every turn. A quick scan of the facts strongly suggests that specific guidelines were never set in regards to the treatment of suspected terrorists. According to the U.S. government, because the subjects were "suspected terrorists" and not officially military P.O.W.s, they were not protected under the rules of the Geneva Convention, so detainees could be treated basically however the hell their captors thought necessary. And with further U.S. attacks on the table, interrogators went to town on their suspects with little or no scruples, leading to widespread abuse, humiliation, and, in this case, the accidental murder of who many conclude was an innocent young man.

Beyond Bagram, we look at the two most infamous U.S. military prisons of recent memory: Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo Bay. In 2004, pictures were released showing the shockingly demeaning and frightening treatment of Abu Ghraib prisoners by seemingly gleeful and enthusiastic guards. All military personnel in the pictures, including Specialists Lynndie England and Charles Graner, were court martialed and sentenced, but when it came out that "torture memos" were released from on high sanctioning the humiliating torture methods, those at the top were relatively given a pass. This reflects the situation at Bagram, where the personnel, who merely followed orders and refused to contradict their fellow and superior officers, were prosecuted and openly chastised, while the officers who condoned the behavior that led to Dilawar's death got off all-but-scot-free.

So at the end of the day, while Middle Eastern tensions have somewhat deflated, and the fears of an imminent terrorist attack by Al Qaeda have significantly subsided, a precedent has been set where the military high command can knowingly sanction abusive and criminal behavior and, through vague and ambiguous terminology, have total deniability in the eyes of the law. The guys and girls at the bottom have been discharged from the military, mostly dishonorably, and while their actions were no doubt inhumane and, for lack of a better word, shameful, those who gave them their orders have been punished with significantly less severity.

Amidst the torture allegations, political scandals, and harrowing footage of physical abuse, perhaps the most affecting aspect of Alex Gibney's documentary is the human face he puts on these dishonored soldiers. It seems that since Vietnam, this country has had an easy time of demonizing its people on the ground during wartime, and wholly attributes atrocities like My Lai and, in this case, Abu Ghraib to the personnel physically present at the time of the events. Right away, TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE sets itself aside from more inflammatory, reactionary responses by looking at these men and women honestly, without judgement, and the effect it has on the viewer is quite powerful.

It's hard to keep in mind, especially if you don't have a ton of friends or family in the military, that, for the most part, these people aren't monsters. They are human beings, like you or me (well, maybe in better physical shape), put in an extreme situation impossible to relate to until you've actually been there yourself. So while it's easy to point a finger at the guys who beat Dilawar's legs and say A + B = C, and if they had simply refrained from striking his legs he wouldn't have died the way he did, understanding the bigger picture takes a little more patience and attention, and that seems to have been one of Gibney's central goals with this doc.

It's hard, at times, to watch these soldiers try and recall these events with something resembling a smile on their face, as if they're fondly remembering their fratboy shenanigans in high school, but it also gets across the sheer level of dehumanization these people go through out there. I don't think these men and women are happy, or even vindicated, about what they did while on duty. In fact, I think it's quite the opposite, that they feel so removed and separated from their vicious wartime behavior, they are, at a certain level, bemused at what they are capable of.

It's like remembering something terrible you did to someone you cared about when you were too young to understand the repercussions of your actions; sure, the guilt of what you've done is still sort of there, but mostly, you become aware of how much you've changed since then, and what you've learned about morality and human decency in the interim. It says something about human nature that these men and women who were dishonored and, in many cases, interred themselves for their role in these abuses, are not only willing to discuss the subject on camera, but do so with some amount of levity. Thankfully, for these soldiers, time, along with confession, seems to have begun to heal these wounds.

The title TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE is referring both to Dilawar's occupation as a taxi driver and a quote from Dick Cheney, which is shown in the film, where he says that "We (referring to the U.S. Armed Forces) also have to work, though, the dark side, if you will. We've got to spend time in the shadows, in the intelligence world. A lot of what needs to be done here will have to be done quietly, without any discussion, using sources and methods that are available to our intelligence agencies." Despite this only slightly veiled approval of torture, the Bush administration was in full damage control mode after the scandals at Bagram, Abu Ghraib, and Gitmo, calling the soldiers responsible for these atrocities "a few bad apples" instead of acknowledging their own part in this behavior. By the end of this documentary, you realize just how cowardly and borderline un-American those claims are.

In an interview for the Wall Street Journal, Gibney mentions how things like the Stanford prison experiment disproves the notion that these disgraced soldiers are all merely psychopaths who blatantly abused their positions of power. "These (soldiers) are regular guys", Gibney maintains, "not bad apples. The administration has referred to the abuses at Abu Ghraib as the work of a few bad apples. But like the movie's title, most of us have a dark side, and we will go there under certain circumstances." When asked about what impact he wanted his film to have on military personnel, he makes things even clearer: "I hope not to have an impact on morale. The military felt it had clear guidelines that were being fiddled with and undermined by civilian leadership. It's up to officers to instill guidelines and it's up to leadership to ensure guidelines are being followed." This puts the blame squarely at the feet of the Bush administration, for their policy choices, the militaristic leanings of its leaders, and rigging the game so that they could appear to be fighting terrorists with maximum efficiency, while maintaining plausible deniability for when the pendulum swung back, and the American people realized that there was a cost they were unwilling to pay to feel safer.

If Gibney's film openly takes the side of the soldiers over the high command and Washington politicos in content, in form it is much more objective. Despite being mostly comprised of interviews, we rarely hear Gibney's voice from off-camera, and when he grants us the rare moment in between the subject's answers, it is in service of a particularly poignant moment that would be impossible to achieve otherwise. He structures his film using chapter titles, starting out with the basic story of Dilawar before dealing with the conditions in Bagram, Abu Ghaib, and finally, Guantanamo, and then jumping back full circle to deal with the details surrounding the Dilawar scandal. If his opinion was blatantly plastered all over this thing, it would have the feel of a fairly rote essay-on-film, but because of the plethora of archival and interview footage surrounding every point, the human element is never far from the surface, and we, the audience, are constantly engaged and, often, unavoidably repulsed.

By using Dilawar's story as an emotional "in" right off the bat, Gibney is able to play things a little more macro as things go on, and the focus becomes broader and broader, until we're watching clips of Bush, Cheney, and Donald Rumsfeld on the American news. By the time we're back to Bagram, and going over the details and timeline surrounding Dilawar's death, we've been given more than enough information to place these events in a proper context, and the questions of "Who should I judge? Who's the 'bad guy'? Would I react any differently in this situation?" have already, at the very least, been asked. Gibney, for the most part, interviews his subjects against a black background, which has the effect of isolating them from time and space, leaving only their testimonies and their body language to speak for them. Some of the interviewees, particularly Pfc. Damien Corsetti (a.k.a. "Monster" or "King of Torture"), would seem utterly horrifying on paper, but Gibney gives them enough space and attention that the nuances of their stories come out, and we are able to see past the obvious surface of these circumstances.

Despite a claim Gibney made to About.com where he claimed "I'm an editor--and I actually see the camera as my weakness," TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE is very visually impressive, on top of everything else. The three primary locations, Bagram, Abu Ghraib, and Guantanamo, all seem very distinct, and we get a visceral sense of what it would be like to be imprisoned in those hot, sweaty buildings. By the time we are shown a press tour of Guantanamo, during which reporters were taken around certain areas of the complex, we have seen enough on our own to call "bullshit"; we know the level of grime that Gitmo contains, and that's obviously not what they were showing the press. Just because there's a half-court basketball hoop and some checkerboards doesn't change the fact that at the time of the press event, over 80 prisoners were undergoing a hunger strike in protest of their unlivable conditions. Gibney's camera catches the hypocrisy and dehumanization symptomatic of these sort of cover-up tactics, but without highlighting them for the cheap seats using repetition and irony the way a Michael Moore doc probably would feel obliged to.

By the time I was done watching this film, I felt physically affected by what I'd seen, complemented by Gibney's adept handling of imagery and music, and going by the film's perfect Rotten Tomatoes score (allegedly the third-highest in the site's history), I wasn't the only one. Roger Ebert, in his four-star review, empathizes with the "sorry, sobered, and confused" interviewees, and concludes by angrily proclaiming, "This movie does not describe the America I learned about in civics class, or think of when I pledge allegiance to the flag." A.O. Scott, in his review of the film for The New York Times, ends with, "(Gibney's) film is long, detailed and not always easy to watch. Plenty of moviegoers would happily pay not to think about the issues raised in TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE. But sooner or later we will need to understand what has happened in this country in the last seven years, and this documentary will be essential to that effort." Andrew Sarris, for The New York Observer similarly lamented, "I hope that every concerned moviegoer sees this film, but I doubt that many will. It is not gruesome enough for the thrill-seeking masses, relying as it does on rational arguments that may not convince people who still believe that anything goes in the treatment of terrorists after 9/11, and that all Islamic extremists are less than human."

If the harrowing nature of the film kept audiences away (it only made less than $300,000 in theaters, a point that Gibney believed was grounds for a lawsuit), I would hypothesize that it's that very quality that secured this film the Best Documentary Oscar over the more popular and accessible SICKO. While the Hollywood features that used the Middle Eastern conflict(s) as a backdrop tended to whitewash the uglier complexities of their subject matter for dramatic effect (or merely commercial viability), TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE looks its subject right in the eye, and doesn't flinch for a second. You get the Abu Ghraib pictures and video footage in full display, you take long, lingering looks at Dilawar's wrecked, lifeless body, and you stare at guilty, shellshocked young soldiers in the face as they awkwardly smile about their time as interrogators. I really can't imagine how it's possible NOT to be affected by this film, and if I was an Academy voter back in '08, the call would be a no-brainer as soon as the end credits started to roll (even then, an interview with Gibney's father, a former Army interrogator himself, still manages to be provocative and moving).

Two years after TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE took home Best Documentary, the Academy gave THE HURT LOCKER six Oscars, including Best Picture, over the biggest hit of all time, AVATAR (despite it having grossed less than not only the rest of the Best Picture nominees of that year, but any winner to date). At one time, it seemed like liberal Hollywood was ready to distance itself completely from the wars of Iraq and Afghanistan, and the young, faceless soldiers sent to do battle there. I'm not saying that TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE was what opened voters' perspectives to see the humanity behind the eyes of a sniper, his spotter, and a bomb defuser (although perhaps the case could be made). What I am saying is that once you've watched TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE, you can't unwatch it. The film's ideas and images are stuck with you for life, and the questions it raises about humanity, camaraderie, and wartime ethics manage to dwarf the already-formidable amount of answers it provides on each subject.

Gibney knows what he's doing. My next move is to check out his docs on "Casino Jack" Abramoff and Hunter S. Thompson, but I know going in that, because of the subject matter and Gibney's stone-faced presentation, TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE may very well end up being the most emotionally and intellectually engaging movie of his career.

PREVIOUS ENTRIES:

UNDERWORLD (1927): Best Writing (Original Story)

SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN (2012): Best Documentary

THE BROADWAY MELODY (1929): Best Picture

THE IRON LADY (2011): Best Actress

THE BIG HOUSE (1930): Best Writing, Best Sound Recording

IN A BETTER WORLD (2010): Best Foreign Language Film

TABU (1931): Best Cinematography

LOGORAMA (2009): Best Short Film (Animated)

BAD GIRL (1931): Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay

DEPARTURES (2008): Best Foreign Language Film

CAVALCADE (1933): Best Picture, Best Director, Best Art Direction

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter