Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

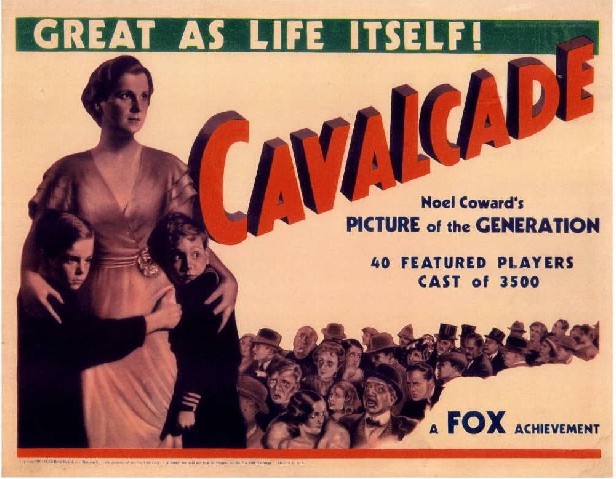

This column will tackle an Oscar winner from each year starting with the inception of the Academy Awards in 1929. My goal is to highlight lesser-known films from throughout cinema history that were able pull down one (or more) of the Golden Statuettes that remain such an integral part of Hollywood lore. I will also take a close look at the actual element(s) that the film was given awards for, with my analysis on how they hold up with years (or decades) of cinematic history in the rearview since. Today, our subject is the 1934 winner for "Outstanding Production" (Best Picture), Best Director, and Best Art Director, Frank Lloyd's CAVALCADE. Next week, (seriously, next week), the topic will be Alex Gibney and Eva Orner's Best Documentary Feature winner, TAXI TO THE DARK SIDE.

When you look at the first five "Outstanding Picture/Production" winners, you see a couple of patterns. Unsurprisingly, the latter four are sound films (to date, the only silent films to take home Best Pic are WINGS and THE ARTIST). WINGS, CIMARRON, and ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT are either war or otherwise epic pictures. More than that, all three are period pictures. THE BROADWAY MELODY and GRAND HOTEL are both Depression-era looks at financial concerns, being rich, and the behavior of those with too much money or not enough of it. And now we have the sixth ever Best Picture which combines all of the above into something that's…been quite forgotten.

Yes, CAVALCADE distinguishes itself among Best Picture winners as maybe the least popular film to have had that ultimate honor bestowed upon it. It was never released on DVD (although it was available as part of Fox's 75th Anniversary Collection), and was only released on Blu-Ray less than a year ago. On its IMDB trivia page, it says that CAVALCADE, while not the lowest-rated Best Picture winner, has (or had, as of April '13) the least amount of votes of any of the 86 winners to date. Even though only two of the "Top Critics" on Rotten Tomatoes gave it negative reviews, the film has a total overall score of 59%. But there it is, a winner of not only the highest honor in the industry, but also Oscars for Best Director and Best Art Direction.

Was this some sort of misunderstood, lost classic that got lost in the annals of time, or was it a CRASH or CHICAGO, a flick that had the right elements to win at that time without anything that would persevere through cinema history? The answer: somewhere in the middle.

CAVALCADE is the story of Jane and Robert Marryot, their kin, their servants, and their lives in Britain during the first third of the 20th century. We open on New Year's Eve, 1899, with England engaged in the Second Boer War in South Africa. Jane and Robert are returning home from celebrating, and as they embrace in their bedroom, we see that the servants downstairs are in a less than jocular mood. Their butler, Alfred, is going off to war, and his wife, Ellen, is struggling to maintain high spirits. Turns out Robert and Jane end up having the same conversation upstairs, as Robert also prepares to venture to the front in South Africa.

Jane's sons are invigorated with the thought that their father is fighting against the South African President, Paul Kruger, but she and Ellen are understandably unnerved by the thought that their husbands will never come home. But, inevitably, the war ends, and both Robert and Alfred are welcomed back to the sound of parades and victorious rejoicing. Alfred buys a bar and takes his family out of the Marryot's employ, while Jane and Robert resume their upper-class galavanting.

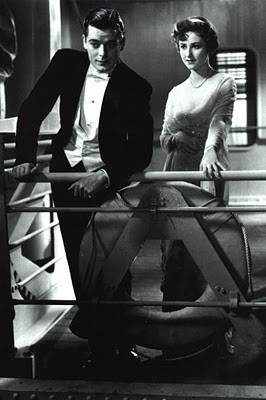

Cut to 1908. Alfred's struggling to run his pub and make rent, and has turned to drink. When Jane visits their home, Ellen makes a point of keeping Alfred out of the house; drunk and ashamed, he storms into the night and is struck by a speeding carriage. Jane and Robert's son, Edward, falls in love with a family friend, but the two are unlucky to take their honeymoon vacation on the RMS Titanic and end up amongst the 1200+ that froze or drowned in the icy water. Then, inevitably, 1914 rolls around, and World War I forces the remaining Marryots out of London to the country.

Robert and his other son, Joe, enlist to fight Germany, and it isn't long before Joe runs into Ellen and Alfred's grown daughter, Fanny (anyone got the guts to name their daughter that today?). He's immediately smitten, and while he carries on fighting in the war, Fanny makes a name for herself as a nightclub singer. Joe proposes to her, but she shoots him down, and he ends up dying near the tail end of the war. We close out the story on New Year's Eve, 1932. Fanny's now a big star, her mother is still pals with Jane, and Jane and Robert are as contented as ever. Having survived two wars and suffered the loss of their two sons, they remain in good spirits as they toast the new year.

If the story sounds episodic, that's because it is. CAVALCADE jumps from era to era, attempting to spin some sort of linear plot out of the Marryots' lives during the first third of the 20th century. It's a novel idea, one that provides the film with a sense of scope and historical relevance, but it sort of muddles up the works, narratively speaking, switching the focus between the fictional characters and the real-life events in an unsatisfying manner.

Just when we're getting a sense of the characters and their dynamics, the script bends over backwards to place a historical context to the onscreen events, and the intimate, emotional stuff ends up feeling forced and contrived. Instead of melding the fictional stuff with reality like a CLOUD ATLAS or FORREST GUMP, the film ends up feeling like a history lesson with some drama tacked on. A simpler story about the Marryot clan and their relationships with their servants, the Bridges, could have been a sweet, fresh look at the upstairs-downstairs dynamic of upper-class British households that GOSFORD PARK and DOWNTON ABBEY deal with.

Unfortunately, the timeline of the film spreads itself too thin over the course of its hour-and-50-minute runtime, and limits itself by spending a disproportionate amount of time dwelling on the goings on of any particular moment. The first 40 minutes deal with the Second Boer war and its aftermath, while everything in between 1902 and the first World War is glazed over in just about 20 minutes. The scenes depicting the funeral march for Queen Victoria, Louis Bleriot's flight over the English Channel, and the doomed voyage of the Titanic are simply backdrops, and aside from the Titanic being responsible for the deaths of Edward and his wife, play no direct role in the plot.

The two wars in the film, the Second Boer War and World War I, have a much bigger impact on the characters, but the specifics of the war are barely glazed over. They could be any major military conflict of the time period, only serving to keep the male characters out in the front and the women characters harried and frightened at home. There is a level of social commentary in the war material, with the international conflicts taking a clear back seat to the personal consequences the wars have on the Marryot family, and an ill-fitting climactic montage firmly cements the film's anti-war stance. The film seems to be saying, "Wouldn't it be great if we could all just get along so that all these couples could simply live happily ever after?"

Historically, the most interesting aspect of the film is that it was produced in the period in between the two World Wars, and I had to keep reminding myself that not only these characters, but the filmmakers themselves, had no idea of the difficulties Britain, and London in particular, would undergo less than a decade later. When they talk about how much war has taken from their family, and how they hope for a peaceful future for Britain, it's heartbreaking in a way the filmmakers could not have possibly predicted.

In '33, communism, not the Nazis, were the looming threat on the horizon, and even then a full-on war like the one that transpired could not have been foreseen for another few years. King George VI's brother, Duke Edward VIII, would even personally visit Hitler with his wife a whole four years after CAVALCADE was released. But when the characters talk about "The Great War", and how much it took from them, you get a feel for the immediate impact World War I had on Europe before Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito instigated a conflict which would end up nearly doubling the prior war's death toll.

While it is all trivialized by the real-life events that transpire in the background, the relationship drama is more successful and engaging than the portrayals of said events. While we meet Robert and Jane Marryot well into their marriage, we feel for the couple, and hope that they can reach a happy end after all the wars and economic hardships finally blow over. The scene on the Titanic, with Edward and his new bride serenading each other and expressing their sublime level of happiness, is touching before an obnoxious push-in reveals the name of their ocean liner on one of its life rafts. It morphs a tragic turn into a punchline, and is yet another example of reality sticking its ugly, unwanted nose into an otherwise decent fictional narrative.

Perhaps the most interesting couple in the film are the Marryots' servants, Alfred and Ellen Bridges. When we meet them, Ellen is understandably worried for the future of her marriage and her unborn child, while Alfred spouts out empty platitudes like, "We have to have wars now and then just to prove we're top dog!" It's funny, but tragic in that marvelously British way he deflects emotional vulnerability with his devotion to king and country. It's a huge victory when he comes back from Africa with an opportunity to run his own business, and leave the life of servitude behind, but without the stability and companionships the Marryot's provided, he becomes a helpless louse.

Alfred's final scenes are maybe the most dramatically engaging in the whole picture, and they perfectly exemplify the theme of classism that runs through the film. As soon as we hear Ellen excusing her husband's absence at dinner with a lie about his "bad leg," we feel for both of them: Ellen is clearly ashamed of the state her husband has ended up in, but she's 100% willing to lie to Alfred and Jane to create the illusion of stability for her guests. The fact that Ellen feels the need to put up such a front to impress her upper-class "friend" at the expense of alienating her own husband puts the importance of status in that time and place in plain sight. It is better to fake it at being respectable than it is to be open about domestic problems, and even if he's drunkenly stumbling about, Alfred is the one who is victimized the most by that system.

Another interesting subplot delves into classism, but ends up going nowhere. The third act of the picture deals with the Marryot's youngest son, Joe, and his romance with the Bridges' daughter, Fanny. The two hit it off, but when Joe proposes marriage to her, Fanny refuses, citing the war, but more to the point, she reminds him, "Your mother wouldn't like it." When Ellen confronts Jane with the news of their children's affair, there's a deep tension between the two that seems directly linked to their former relationship as master and servant. This seems to be the conflict that will drive the rest of the film, especially considering that the war is ending and Joe will be returning home, but at the tail-end of the scene, Jane gets a telegram informing her of Joe's death.

This is sort of indicative of the whole film's sense of drama. Just when things are starting to build on a human level, the narrative shuffles them off and moves on to the next "event." The only through-line of the film is the character of Jane, who watches her husband and her son go off to war, and grieves over both her late sons. Watching her send off her son to the war front after we've seen her do the same for her husband only a few years prior is a nice progression, as the years and experience have hardened her. By the end, as she is toasting a childless future with her husband, she is visibly changed, and even if her character doesn't have any sort of real arc to speak of, we see the impact the film's events have had on her. Actress Diana Wynyard, who later appeared in GASLIGHT and ISLAND IN THE SUN, was the only actor in CAVALCADE to receive an Oscar nomination, and even the source material's author, Noel Coward, described her performance as "sincere and beautiful."

The other characters in the film are, for the most part, far more stodgy and theatrical, and are very rarely allowed any sort of real emotional content. Clive Brook, as Robert, probably suffers the most, as his character is the second lead of the picture, yet he is merely a collection of elitist mannerisms and icy detatchment. He never seems wholly present, and when he returns after long stretches offscreen, he seems hardly affected by his experiences; he ends the film the same boring, upper-class fellow he started out as, and it's hard to believe that a wealthy veteran of two wars who's lost both his children can close out the film as cooly complacent as he seems. He plays his role strictly for laughs, and it creates a bizarre contrast with the dour events that are occurring.

Their sons, played by John Warburton and Frank Lawton, are broadly portrayed, with Warburton's Edward as the stalwart gent and Lawton's Joe as the go-getting, lovestruck younger brother. Una O'Connor plays her Ellen Bridges for laughs, which inadvertently makes her working class character look desperate and foolish, particularly when she starts boasting about how "some of us are getting on better than others" and how her daughter "knows all the best people." Herbert Mundin, as her husband, Alfred, has it the best of the supporting cast, creating a tragic, conflicted character with a relatively scarce amount of screentime. He may lay on the drunk act a little bit thick, but he never lets Alfred's humanity sink too far from the surface, and we empathize with him as he realizes the extent of his wife's shame. Ursula Jeans, as Fanny, has some nice musical numbers, but she's not given much to work with in her dialogue scenes, and her character, a large part of the third act, ends up being fairly forgettable. I give the actors credit for trying to inject energy and life into their roles, but they're at the mercy of the scattershot script, and for the most part, end up coming and going without much fanfare, or any really interesting dramatic moments.

Director Frank Lloyd won his second Oscar for this film, after winning three years prior another period film, THE DIVINE LADY. He'd receive a third nomination for the original MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY two years later, and was unofficially nominated for two other films the year he won his first award. His work here is successful at opening up Noel Coward's original stage play into something big and cinematic, but his efforts are inconsistent. At certain moments, the editing, score, and shot choices are grand and sweeping, but other scenes feel like actors reading dialogue on a stage.

He fails to do the one thing that any director of this script would be tasked with, which is creating the feeling of cohesion amidst all the different eras, events, and characters. The film feels like a collection of scenes more than it feels like an actual movie, and while I find Coward's source material somewhat at fault, I reckon a stronger vision for the project may have been more successful at tying it all together. Lloyd beat no less than Frank Capra and George Cukor for his CAVALCADE Oscar, but I can't imagine why; much of what doesn't come off as a filmed play is garish, over-the-top, and clunky.

The Oscar-winning art direction by William S. Darling and Fredric Hope is impressive in its depiction of upper-class British life, and the various time periods in which the story takes place, but the sets are sometimes claustrophobic and phony-looking. I'm not saying the Titanic always needs to look like James Cameron's ILM-assisted version, but it does need to look like a boat at sea, and it's one of Darling and Hope's more glaring errors (although it must be said that part of a director's job is to elevate each department's craft into something you can call "cinema").

When it won Outstanding Production, CAVALCADE beat, among others, the Busby Berkley-choreographed 42ND STREET, the Helen Hayes/Gary Cooper-starrer A FAREWELL TO ARMS, Mervyn LeRoy's I AM A FUGITIVE FROM A CHAIN GANG, and Cukor's LITTLE WOMEN (which, interestingly enough, LeRoy would remake 16 years later). I have not seen these other films, but I am wholly aware of their existence, and their place in film history. Before I settled on watching it for this column, I could not say the same for CAVALCADE. It makes sense that 20th Century Fox didn't feel the need to make this available on disc until a letter-writing campaign inspired them to release it on Blu-ray. Aside from its historical relevance, it is largely unremarkable, and watching it 80+ years later can only decrease the luster that its two major awards (and one significant nomination) grant it..

Having said that, it's not a dog of a film. There is some interesting, engaging stuff in this film, if you have the patience to sift through the rest. The examination of class in England in the early-20th century is occasionally very cutting and revealing, particularly in the first half. Diana Wynyard does a memorable job of playing a character who's run through the ringer by the sheer nature of being a wife and mother over the course of two major wars; her nomination doesn't feel like the Academy misstep that the film's wins do. And there really is no better way to see how World War I was thought of before it got a bigger, badder sequel than to examine portrayals of it in the art and media of the time.

But Best Director AND Best Picture? I can only guess that nostalgia, anglophilia, or a craving for melodrama are what inspired voters to choose CAVALCADE over the works of Capra, Cukor, LeRoy, and Busby Berkeley of that year. Of the following ten Best Picture winners, six were period films, four either took place in the U.K. or focused on British characters, and two (YOU CAN'T TAKE IT WITH YOU and REBECCA) were either based on plays or took place primarily in one location. However, I'd make the argument that this film, more than those, seems to have won based on whatever attractive traits it possessed, and wasn't recognized as much for its content as much as it was for other factors. At least, that's what it seems like today.

PREVIOUS ENTRIES:

UNDERWORLD (1927): Best Writing (Original Story)

SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN (2012): Best Documentary

THE BROADWAY MELODY (1929): Best Picture

THE IRON LADY (2011): Best Actress

THE BIG HOUSE (1930): Best Writing, Best Sound Recording

IN A BETTER WORLD (2010): Best Foreign Language Film

TABU (1931): Best Cinematography

LOGORAMA (2009): Best Short Film (Animated)

BAD GIRL (1931): Best Director, Best Adapted Screenplay

DEPARTURES (2008): Best Foreign Language Film

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter