Nordling here.

Yes, I'm starting another column, and yes, I've been guilty of abandoning columns before. I have no excuse except laziness, I guess, and having other life commitments, but my intent is good if that helps. (It probably doesn't.) I love to write about movies, but I'd be lying if I say it is easy for me. I have a limited perspective - I don't have any degrees in Film, just a lifelong appreciation of cinema and an eagerness to learn more. I guess I'm an okay writer, and I'd like to think I'm pretty good at analyzing a film and looking through to its context, its essentials, the pieces that make up its value. But frankly, much of the time I feel like I'm winging it, and just writing from my gut and my heart. In short, I know what I love and why I love it, but articulating these things is difficult for me, and I want to get better at it.

So, another column, and this time I'm diving into a genre that is very close to my heart, and yet I feel like I've barely explored it in any real detail - the samurai film. Why do I love samurai movies? There's powerful emotion in them, and the heroes are deep oceans of stillness, and the enemy isn't necessarily the foe opposite them, but their own sense of honor and their place in the world. So many samurai films are about a hero out of time and place, adapting to a world that has moved beyond them or a society that simply cannot live up to the ideals that the samurai has. Often times these samurai heroes subvert the very idea of bushido for a greater good or truth, like Toshiro Mifune's nameless hero of Akira Kurosawa's SANJURO and YOJIMBO, or SEVEN SAMURAI's Kambei, who shaves his topknot, an absolute scandal to the samurai code at the very least.

Perhaps I respond to the swordplay, and the orchestration of action in many samurai films. Truth be told, there isn't much action in a lot of the great samurai films of old; action is used with true purpose and not simply to excite the audience. The best samurai action scenes are more character-building than anything - the threat of violence is always there, and when finally the sword is unsheathed, it is used to maximum effect. Some of the most amazingly shot action sequences are in chambara films. Akira Kurosawa shot action to masterful effect, something that I wish many directors would pay attention to - many samurai films are brilliantly choreographed and visual feasts to behold.

I'm also admitting another place I have weakness - the history of Japan during the Tokugawa era, when most samurai films take place (an interesting exception is SEVEN SAMURAI, which takes place a few years before). I'm going to explore this more over the coming year and read up as much as possible, so that I may grow to understand the historical aspects of the genre. But one of the aspects I respond to the most in samurai cinema is of an older world passing away, and a new society forming from those foundations, where a samurai's ideals may not be in synch with the coming new order to follow. So many samurai films touch on that aspect that it gives these films real thematic weight. It's not simply Japan in flux, but so many other ways of life as well. Even a movie like Clint Eastwood's UNFORGIVEN uses these themes. As I get older, perhaps this is what resonates with me the most.

I freely admit to loving the genre yet having little film experience with it, which is why this column will be an exploration for me more than it is for the reader; considering how many samurai films there are, I know I'm a neophyte. I've seen most of the Kurosawa samurai films, and a few outside like SWORD OF DOOM, or the SAMURAI Trilogy, and not much else. I bought the ZATOICHI Criterion box set recently, and that is perhaps the largest blind purchase I've ever made. I bought them on reputation alone, and the fact that I love the genre so much. I will definitely be diving into those for this column, as well as many others, both old to me and new to me, and I'm willing to consider recommendations as well. Mostly, I want to share this genre with others, and find great movies to enjoy together.

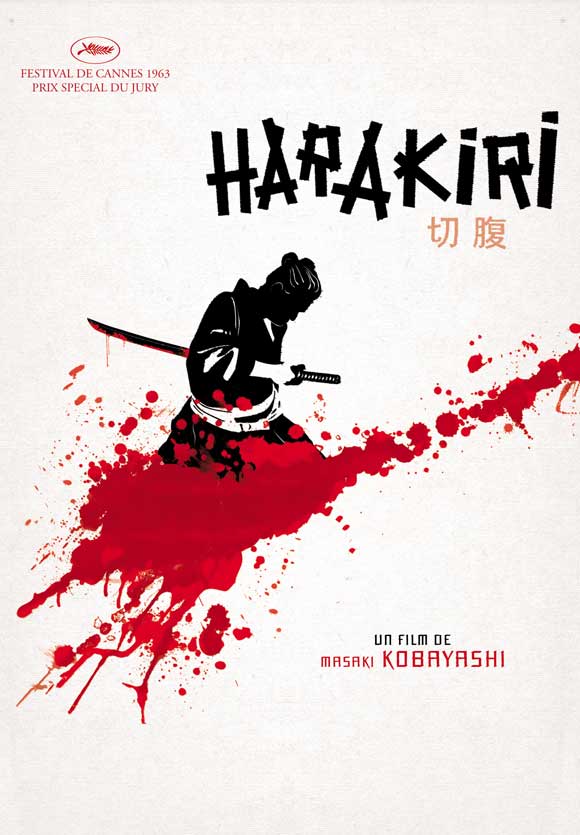

My first film for the column is strange, considering that I'm writing in celebration of the genre. Donald Richie calls Masaki Kobayashi's HARAKIRI an "anti-samurai" film and he's very correct in that respect. So many other chambara films celebrate the honor and code of the bushido, with samurai as the heroes - taciturn men who nonetheless fight for the honor of themselves and their master. Not so HARAKIRI. Hanshiro Tsugumo (the wonderful Tatsuya Nakadai, as noble here as he is evil in THE SWORD OF DOOM) comes to the Iyi estate with the intention of committing seppuku, or ritual suicide. However, Counselor Saito (Rentaro Mikuni) of the Iyi Estate is suspicious - it seems that across Edo there are unemployed ronin going to various estates threatening to kill themselves in their courtyard, and the estates, to avoid embarrassment, offer the ronin money for them to leave. Saito suspects the same of Tsugumo, and tells him the story of a young man, Motome Chijiiwa (Akira Ishihama), who recently tried to extort money from the Iyi estate and met with a particularly bad end.

Tsugumo, however, assures the Counselor that he absolutely intends to kill himself, and that he wishes the estate to witness it. So we begin stories within stories - we learn of Tsugumo's life, and what brought him to this state, and we learn the true meaning of samurai honor. While the ideal and tenets of bushido may bring a man his own sense of nobility, they do him little good if he has no master and is forced to take care of a starving family. As Tsugumo eloquently states, he could not live on air alone. Tsugumo's story, and how it intertwines with Motome's, is a tragedy made worse in that Tsugumo tries to live to the ideals that he has based his life around, and that they have completely, utterly failed him. All he can ask for is death, but first he will show these men what the samurai way of life really means - a life full of bluster, ego, and pride, but ultimately empty of meaning and honor. It is Tsugumo's farce, that he has lived the code every day, and all that it has brought him is tragedy and death - the death of his friends, his family, and a life devoid of meaning and victory.

Again, in HARAKIRI we can see the clash of the old and the new - set in the early years of the Tokugawa period, the samurai way of life was quickly the standard throughout all of Japan. We can see the context playing itself out - it's no accident that Tsugumo comes from Hiroshima, and Kobayashi's film is witness to the conflict that was very apparent in post-war Japan, a Japan that wanted to put the war behind them, but also a Japan in danger of forgetting those lessons of the past. There is no easy resolution in HARAKIRI to this question, and Masaki Kobayshi's film, along with the script by Shinobu Hashimoto, perhaps the greatest screenwriter of samurai cinema who ever lived, asks more questions than it answers, and leaves the audience to determine which way of life should be triumphant. Perhaps there are no simple answers, and that Kobayashi suggests that honor is nothing without altruism, that the tenets of bushido mean nothing without helping a fellow human being in need. Both Tsugumo and the samurai of the Iyi estate are trapped by honor, in a world where the simple slicing off of a topknot means death. It's just hair, after all. What it represents is merely an affectation, and it all becomes a waste of life.

I love how Kobayashi shoots his action sequences, with long, sanguine takes and angles that fill up the 2.35 to 1 screen, and yet at the last moments he pulls back, denying the audience of the release of battle. The moments of respite in Hashimoto's script are few - Tsugumo sitting with his good friend Jinnai (Yoshio Inaba) before everything goes badly with the Fukushima Clan, or Tsugumo's brief moments of joy with his grandson Kingo - and Tatsuya Nakadai is so good in HARAKIRI. We see idealism turn to loss, loss to determination, and determination turn to tragedy, and Nakadai puts it all in his anguished face. By the time we come to the end of Tsugumo's tale, his voice is the voice of the dead, speaking for the senseless loss of his loved ones and a way of life that has betrayed him at every turn. But Tsugumo is determined to die the only way he knows how - with samurai honor, as empty to him as the suit of armor that the Iyi estate treasures, but it is all he knows. HARAKIRI is a great film, and while it is a chambara film through and through, Masaki Kobayashi asks what honor - true honor - really means when the strictures and rules of such honor bind so strongly that to break them, even with the best intentions, is a betrayal. What does it mean to be a samurai, someone supposedly full of good and honor, when it causes so much suffering?

Next week, I'll be hosting a screening of Akira Kurosawa's SEVEN SAMURAI at the Alamo Drafthouse here in Houston, so my Samurai Sunday roster will be that movie. This year marks the 60th anniversary of what is, in my opinion, the greatest film of all time, and I'd love for you to join me if you live in the Houston area. For now, I swear I'll keep this column up the best that I can. So next week - SEVEN SAMURAI, and how it made me the film fan I am today. Until then, remember - by protecting others, you save yourself.

Nordling, out.