Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

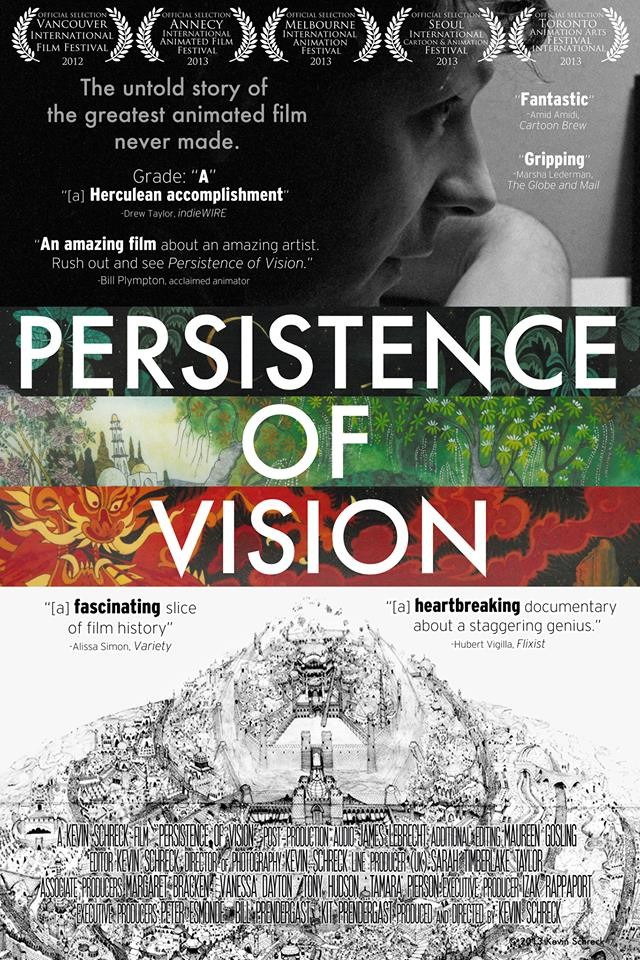

Even if you've never heard of it, Richard Williams' THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER is a legendary picture. Though the released version (retitled ARABIAN KNIGHT, then re-retitled back again) was a box-office bomb, the 30-year production time of the film and the reputation of its various cuts have made the film a mainstay of animation, even before its "completion". There are few cinematic artists who had the talent and knowhow to be successful in the industry, but instead chose to use their skills and contacts to get their own personal passion projects off the ground. Among them, Richard Williams is one of the lesser known, and Kevin Schreck saw to remedy that when he began work on his documentary about Williams and THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, entitled PERSISTENCE OF VISION. When I told Mr. Schreck about my intention to tackle THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, as well as his film, he graciously offered me some time on the phone. Among other things, we get into the

VINYARD: If you don't mind, just talk a little bit about the origin of your relationship with the movie, and what inspired you to do a feature-length doc on this unfinished picture?

KEVIN: Well, like a lot of people growing up in the late '80s, early '90s, I was obviously very interested in animation, inundated with animation, and it was just at the time period when good animation was happening, finally, after the dark ages of the mid-'80s and- well, pretty much everything after…the '50s.

VINYARD: After Disney died, I guess.

KEVIN: Even then. At least 20 or 30 years of crap, which I wasn't privy to. So (WHO FRAMED) ROGER RABBIT shows up, and for me, even though I was very young, I noticed it was something special, partly because- maybe largely because it was just a bunch of cartoon characters I'd never seen together in the same shot, in the same movie, interacting and stuff.

VINYARD: Right, of course.

KEVIN: You know, Bugs, and Mickey, and Daffy, and Donald, and all that. So even that was sort of a special token. But it felt different too. So I saw ROGER RABBIT quite young, and I wanted to try out animation really young. I was trying to do some stop-motion stuff because I was really into Tim Burton, and KING KONG, and all that kind of stuff, and WALLACE AND GROMIT and Aardman, and all that. Every animator I asked, whether in person or via e-mail, I'd ask, "Well, where do I start?" And they all said, "Dick WIlliams' book." Dick William's book (The Animator's Survival Kit)had only been out for a year- maybe less than that even. It had only been published less than a year or something, and already, it was the go-to, and that is a position that has not been usurped since. In fact, if anything, it's even more the gold standard of animation how-to.I was aware of this guy's work, so I was like, "Oh, it's the ROGER RABBIT guy." But one thing stood out to me while I was reading this book, because obviously, what I was learning from it was hugely important, hugely influential and inspiring, and just essential to animate the basics. But I was wondering why I didn't know this guy's work, or seen his name on anything. It wasn't like Walt Disney or something like that, or even Ralph Bakshi, who've done all these projects. How come I only knew this guy from ROGER RABBIT? Was I just ignorant, or had he only done that, you know?

So a few years pass- this is a long story I know- and I've just got to college, and a friend of mine tells me online that there's this unfinished masterpiece of animation, and that caught my interest for obvious reasons. I started watching it. It was the RECOBBLED CUT, and it was a terrible quality on Google Video (remember that?), so I stopped half an hour into it because I felt if I'm gonna watch this thing, it's gotta be in the best way I can. So I got in touch with Garrett Gilchrist (the author of the RECOBBLED CUT), and I just told him, "Anything you have, send it to me. I'll even pay you for it. I'm just so fascinated by this beautiful film, that was just so strange and complex."

And then I realized, oh, wait, that's the guy, that's Richard Williams! It kind of filled in this whole gap of what this thing was, and I found the backstory of THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER to be even more interesting than the film itself, and certainly tragic, and epic, almost like operatic. It's just a fascinating story about the creative process, and a creative person.

VINYARD: So how long did you work on the movie for?

KEVIN: As soon as I saw THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER, I thought "This would make a great documentary, but I don't think I'm gonna do it." But even then, I couldn't help but immediately start researching it, just recreationally, because I was just obsessed with this story of obsession. It was contagious, you know? I'd been researching it for about two years, and then I had a little job at Dreamworks Animation in Glendale, and I spoke to a lot of animators and directors there over lunch or whatever, and I'd mention some projects I was thinkingabout doing. THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER came up, and they were talking about how this was a story that wasn't getting any…it was only getting older and older, and more distant in terms of time. People were dying off, memories fade. And I thought, maybe I'll just take a shot at it. I'm always going to feel unready for a story of this size, but I figured I'd give it a shot. So even though I was telling myself, "I'm not going to make this movie," I was already in development and pre-production for two and a half years. And then I figured, with that motivation of (the animators) talking about the film, and how it was this sort of lost chapter of cinema history that was only getting more and more lost, I started e-mailing people who worked on the film or at the studio, seeing if they'd ever possibly, hypothetically be interested in maybe participating in a documentary about this thing, and most of them said yes. The vast majority actually. And even those who felt that they weren't in a position to talk about it still felt it was a story worth telling. That was quite motivating, so then I shot it in London for the most part, a little bit in Toronto and New York, in 2010, and the version that got shown around in festivals was put on its final print last year in September, so 2012. It's a movie I kind of made- it's kind of weird to say this, but it's a movie I made for myself just because I wanted someone to make this story, but I didn't think it was a definitive version. I didn't think anyone would ever see it, or have any interest in it, but it just snowballed more than I ever imagined. It's been at 40-something festivals all over the world, it's been crazy.

VINYARD: There's a lot of licensed footage in the movie. Do you think it's going to be a challenge to release it in theaters or on Blu-ray maybe?

KEVIN: It will be, and it is, but also, I'm not really aiming for it. Because again, it's like…I've had a lot of offers from distributors, actually, and they love the story, they love the documentary, and they get really excited about it. And then, a few days pass, they kind of sober up after all the energy and excitement, and they realize, "Wait a minute, this kid doesn't have any money, and we don't want to pay for all the clearances," so they kinda just…they don't say they're not gonna do it, they just kind of fade away. (laughs) They just say, "Maybe later," or something. In other words…the fact that anyone's even seen the thing, certainly to this magnitude, is way beyond any expectations I had. I'll probably show it somehow in some way or another, but I'm never expecting really to put it out on DVD or Blu-ray in any official capacity, or a theatrical run or anything like that. It's had some good brief runs for like a week or something, or a few days, at some really good cinemas and festivals, and there are several coming up. There'll be a run in early January (10-16) in Toronto, and it'll be showing in Missoula, Montana, and it'll be showing in Brussels, and a couple other places to that I can't mention quite yet. But it could still happen Even 15 months after its world premiere, it's just sort of trickling. There's no money or force behind it to have a big release, we just show it as much as we can. It's a small project, at the end of the day, you know?

VINYARD: Ideally, after this workprint screening at the Academy a couple weeks ago, hopefully someone gets together a nice omnibus Blu-ray with all the cuts, and your feature as a special feature, at the very least. That would be great.

KEVIN: Well, I hope we don't need all the cuts on it, 'cause most of the cuts are pretty…it's unprofessional of me, but I've never been able to sit through the ARABIAN KNIGHT (Miramax) cut in one sitting. I have to watch it in like 5 or 10 minute intervals, and then I go out for a walk in the dark all alone, or just sleep on it, (I laugh) When I was in editing, I kind of just jumped around, and selected parts which I thought were most persuasive at showing just how god-awful it was. And it wasn't hard to find ones that did; it was more of a difficulty figuring out which ones to choose among the abundance of atrocities that were pulled in that thing.

VINYARD: Full disclosure: I actually really liked that cut as a kid.

KEVIN: Oh yeah?

VINYARD: Particularly, I actually really did respond to Jonathan Winters voice-over as The Thief, but after seeing the versions without the dialogue, I can't imagine going back and sitting through that again.

KEVIN: I mean, he is a funny guy, Jonathan Winters, and it's weird because I'm almost certain that they hired him because of the success of having Robin Williams in ALADDIN. Which is so ironic in another way because there are influences from the artistic standpoint, certain character designs and elements and things like that, but they hired Jonathan Winters, and he was the guy who inspired Robin Williams, 'cause he's his hero! So it's this wacky sort of unhinged improv comedy, of like morphing voices and personalities.

VINYARD: Except he doesn't interact with anyone in the whole movie! He's muttering to himself the whole time! But when it's silent it's golden.

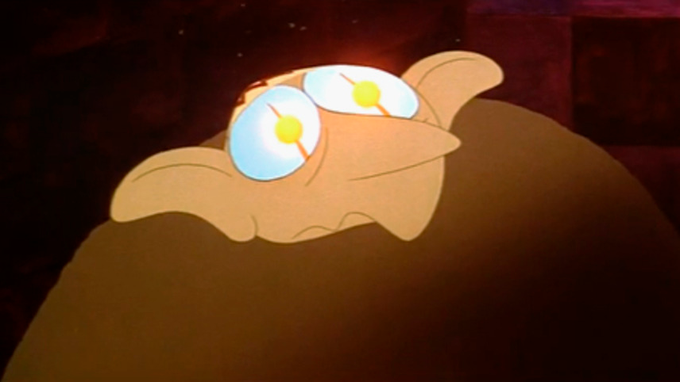

KEVIN: Sure, that's a good way of putting it. As I was putting together my documentary, I realized that I had actually seen some of the ARABIAN KNIGHT cut on television when I was like 10 years old or something, and I'd completely blotted it out because it was such a surreal experience. Some surreal experiences stick with you because they are so surreal, or traumatic, or exciting, but this was one that was just too dumbfounding that I couldn't even process it. In fact, when I was watchin git, I saw all this crazy artwork that was like Persian miniature-meets-M.C. Escher. Really detailed animation. Before I knew anything about filmmaking or animation, you can still feel, on a tactile level, on a visceral level, that something was different or off about it, and I heard the voice by Jonathan Winters, and I must've thought at the age of 10, not knowing anything about anything, that there was something wrong with the television set. Like the visuals of one station were coming in and then the audio from another station was coming in. It was some sort of weird technological overlap between the two channels or something. And I think it just confused and annoyed me too much, and I stopped after 5 or 10 minutes, and I resurrected that memory 12 years later as I was editing. I was like, "Wait a minute, there's something about this that's so familiar!"

VINYARD: Do you think that striking element of the animation is maybe one of the factors that kept Warner Bros. and, later, Miramax a little cool on the project? Maybe they thought this wasn't like Disney style, very family friendly, very big-eyes, round edges, easily palatable children's animation?

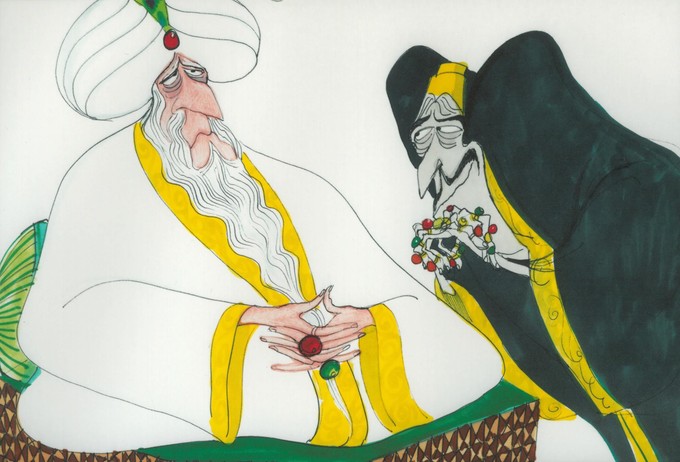

KEVIN: Yeah, I think so. Not just the animation, I think more the way the movie was put together, because it has no- as Williams intended, it doesn't have any pop culture references- I mean there are a couple. There's a FANTASIA joke, with The Night on Bald Mountain, and The Thief does something that's from- he scampers around like Harpo Marx in DUCK SOUP in one shot. But there aren't really any pop culture references that are more recent than 1942 in it (I laugh). Even those are few and far between, and they serve the story. They're not like FAMILY GUY gags, where they just show up and disappear, and it's like, "Well, what the hell was that?" They're kind of integrated into the picture a bit more.There's not like four or five pop songs where you have the schmaltzy ballad version at the end, where you have the pop stars that no one's going to remember after 20 years or 10 years at the end credits, which of course they did tack on to the Miramax version. And, of course, not even from an aesthetic standpoint, but a practical standpoint, the story just was not there. I mean, it's an enthralling experience, but for me, I think THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER as Richard Williams envisioned it is more of an art project than it is a Hollywood movie. It's this guy and this team of brilliant artists that he was able to corral and command to explore what you can do with the medium, and have fun with it, and work your ass off, and torture yourself over it to just make these amazing images come to life in all these different ways. Some scenes are entirely exercises of principals that he learned from the old guys. They're just noodling and experimentation with them. It really is an experimental art project in the most literal sense. It had a story, but when you watch the workprint, all of the pretty, glossy, finished sequences are The Thief goofing around. All this political stuff, or narrative stuff, with the king, and the princess, and the cobbler…

VINYARD: Which all got co-opted by Disney for ALADDIN.

KEVIN: Those were just storyboards. Storyboards that Warner Bros. pressured Williams to do, and that he did in about two weeks time in early 1992. Even then, he coudln't help but do a fantastic job. Those are gorgeous storyboards, and really ornate in detail, more than most storyboards need to be, but I guess he couldn't help himself. It's an experience that is exhilerating, fascinating, and beautiful, and frustrating, and dumbfounding, and innovating. It doesn't work as a Hollywood film, 'cause that isn't its goal, even though Williams had to say it was, or tell himself it was, in order to get the money to finance the thing. Long story short, I think that Warner Bros. sobered up and saw that, "Well, he certainly knows his stuff in terms of art and craft." They saw that with ROGER RABBIT. There was an instance in which Greg Duffell, whose first gig in animation was at the age of 17 in 1973 and 1974 at the studio. He was this naiive, enthusiastic little guy who loved Looney Tunes cartoons, and he'd come from Toronto, like Williams had. He saw Ken Harris making that scene with the brigand and the snake, which was ultimately cut even from the workprint, but fast-forward to 1991 or even early 1992, and he's meeting with the head of Warner Bros. animation, Jean MacCurdy, and she says, "Well, I don't know anything about animation!"

VINYARD: (I'm dying of laughter) Makes a lotta sense!

KEVIN: She said, "I'm not quite sure what they're up to over in London. I saw this really good looking scene though, it was in pencil-test form," and Greg asked her, "Well, what is it?" Out of curiosity. "It's the scene of this brigand, and he's talkin' about Salome, and he's got this snake going around his head, and it's in pencil-test form, so I guess they just finished it." And Greg realizes to himself, "Holy shit, they are digging up scenes they discarded almost 20 years ago to try to convince the backers that they are making progress." It was just insane. At the end of the day, they were trying to bring music and voices in. Brian Eno showed up at the studio, George Martin showed up at the studio, Paul McCartney showed up, Roger Waters even wrote a little song. They had John Patrick Shanley, the playwright, he did some lyrics for something that was discarded because it just wasn't cutting it.

VINYARD: And this is all at Warner Bros.

KEVIN: Yeah, this is all during that 3-year time span at Warner Bros. They were trying to make things happen, but it just was not budging. Disney was getting their product out faster and slicker and cheaper, and in a more family friendly way that would plant a family of four into the seats with their overpriced popcorn and sodas, and they get the ticket sales, and make opening weekend the most precious- seems to be the only time that mattered, 'cause Hollywood is the way it is- make it count.

VINYARD: And then Miramax, when they bought the movie, it tanked. I don't even think it made a million dollars.

KEVIN: Nobody won. Some of this is conjecture, but some of the facts add up, and it doesn't really seem that they were even interested in making it a success. I think that they just felt obliged to release it theatrically. They released it into a couple of hundred cinemas in North America only in like late August, which is such a dead zone. It's too soon for the Oscar-worthy movies, and too late for the Summer blockbusters. They were just getting it out of the way, I think. They didn't have any advertising. I know one person who was working at Miramax at the time in the mid-'90s when they had all these hits, PULP FICTION, CLERKS, etc.

VINYARD: ENGLISH PATIENT.

KEVIN: He never saw THIEF AND THE COBBLER, or ARABIAN KNIGHT, on any of the things he was looking at, and he was in marketing there. They just didn't care, I don't think. Then they tacked on these weird references to ALADDIN, like the prologue with Matthew Broderick with his bland little voice saying, very ironically, "Long ago, long before Aladdin…" (laughs) It's just really funny that they'd try and make it seem like it's part of that universe just so it could piggyback, as if it was another sequel.

VINYARD: To make the movie that got ripped off not seem like the movie that ripped it off.

KEVIN: All that too. Maybe also just saving their asses too. I think for the most part it was, to them, a sort of product tie-in, as if it was a pseudo-sequel. But I think you're right, if anyone was paying attention, which no one was because no one saw the damn thing. New York Times said, "Some of the best animation ever," but that's the only thing they could say that was nice. They were gushing about the animation, and they were totally right in saying that. That's the only thing that worked in that cut.So nobody won. It was a critical bomb, it was a financial bomb, it was an artistic bomb, certainly.

VINYARD: Who owns the workprint? Who owns the last thing that Richard Williams gave them in '92? Would it be Warner Bros., would it be Miramax, or would it be Williams himself? How would that go about getting published on home video?

KEVIN: No idea. I assume it's some extension of Disney. Miramax isn't really around anymore, now it's the Weinstein Company, but Miramax was under the Disney umbrella, as we both know. I don't know if you were able to salvage one of those programs last week, but I know Don Hahn was credited- "Special Thanks to Don Hahn, Imogen Sutton, Miramax, Visual Icon, and The Walt Disney Company." Mo Sutton is his wife, and she's his producer, and she always has him on a leash. I don't know what Visual Icon is (they seem to be a licensing company), and Don Hahn has been championing the film unofficially, because he's so involved with Disney as a producer of all their movies like THE LION KING, and NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS. He directed that WAKING SLEEPING BEAUTY thing that was interesting, but very protected. Very Disney.

VINYARD: Very in-house.

KEVIN: That's a good way to put it. Very in-house. Most of the stunning drama came from the Menken-Ashman relationship, which is good drama, but it's not really about the animation history. It's a love story that ended sadly.

VINYARD: Your doc doesn't really feel like that. You have a ton of archival footage of Richard Williams second guessing his animators, a lot of…you deal with the sort of interpersonal conflicts that were going on in his studio. How did you get your hands on all that archival footage?

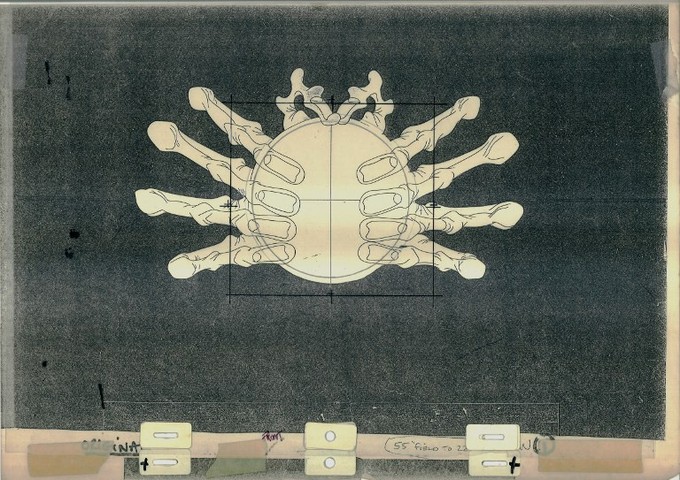

KEVIN: Garrett Gilchrist had a lot already, so I'm kind of standing on the shoulders of giants, because I wouldn't have even known about this story had it not been for his own obsessive research and work. A lot of it also came from other collectors, and animators who worked on the film. They had some archival footage, or different footage, or higher quality footage, and all the pencil-tests and things came from that too. One animator I spoke to, a special effects animator, in the last few years in the '90s, the most tumultuous time, had a stack of pneumatic tapes, which of course is this ancient format that even I don't know much about. He was generous enough to transfer all this material, and it turned out to be over two hours of animation which nobody had seen in over 20 years, some of it dating as far back as the late-'60s. It was incredible. That really made the documentary possible. I did have this archival footage of Williams from like 1966, and something from 1970, and '74, and 1982, and then 1989, and that shows him sort of evolve and transition as a human being, which is important because ultimately, it is a documentary that's sort of a character study more than it is about an animated film. But, because it's a visual medium, you still need to show the animated film that we're talking about, and once I saw that footage of like gears and levers rotating in the War Machine sequence in pencil-test form, and The Thief and Zigzag and all these other characters moving around in all their transitional, evolutionary forms throughout the decades in rough animation, that's when I knew the documentary was actually possible. Thankfully, some of that earlier stuff is in the public domain, but a lot of it isn't, so that's the thing.

VINYARD: That's one of the challenges, yeah. It's interesting that you frame the film as a character study, because I guess the one major name involved with the production that isn't featured in an onscreen interview is Richard Williams himself. Can you talk a little bit about pursuing him if you did, or, knowing that he didn't like to talk about the film, did you just not even bother?

KEVIN: I was always prepared intellectually that he would say no, but I figured it was still worth a shot. This is another rambly story, but when I was organizing the interviews in London in the summer of 2010, the German fellow in my documentary, Michael Schlingmann, I'd heard he was considering at some point doing a reunion of sorts with some of the crewmembers. That caught my interest, so I asked if he was still interested in that, once I had him in the bag, so to speak, or at least scheduled to do an interview. And he said he'd kind of forgotten about it, but now that we were talking about my documentary, he said he was interested again. So we corroborated our lists, our address books, of people who had worked at the studio and worked on THIEF AND THE COBBLER, and with Richard Williams, and still had a bigger number, bigger than either of us expected, of people meeting at one of the pubs they used to frequent in SoHo. That was great. We had people from the '60 through the '90s working on that film meeting each other for the first time in many years, many of them meeting for the first time ever 'cause they were so far apart temporally.I met Roy Naisbitt there, and Roy is not just an incredible artist, I mean his brain belongs in the renaissance era, he's just an insane visual artist, but he's also an extremely friendly person. Really nice bloke. I got his phone number, and I called him the next day after the party at the pub, and I said, "Roy, a couple of the animators, my line producer, and I are going to go over to where the old studio was at 13 SoHo Square." That green building that was in the opening shot of my documentary. "So I was wondering if you may wanna tag along, share your stories," because it was going to be kind of a ghost tour. Obviously, that footage isn't shown in the documentary. We were in London for two weeks, and I thought, "We're here, we're not going to be back, what have we got to lose. May as well shoot it in case we use it, and if we don't, fun experience. And we have access, because the guys who are in that studio totally know about the history, and are huge Richard Williams nuts." So we had the option, and we figured let's see if Roy wants to come. Roy loved the idea, was very enthusiastic about it, but he said, "You know, maybe I should check to see what Dick thinks." And I hadn't even considered that as a possibility. I said, "Sure! In fact, maybe you can even ask if he might be interested in talking a little bit too!" And he said, "Sure, but don't count on it. If he says no, I might have to say no too, because I don't want to hurt his feelings. We're close friends." They've been friends for like 50 years, half a century, so I totally understood.

Roy hung up, about 45 minutes pass, I'm pacing back and forth in Kensington, and Roy calls me back, after all that time, and his enthusiasm has plummeted. He sounds a little beaten up emotionally, actually. I feel a little bad, but they've probably been through worse squabbles. He said, with some sadness in his voice but also a twinge of annoyance, "Poor Dick," he said, "Dick still won't talk about the movie. He says that only he should talk about the movie and nobody else. He never will talk about the movie, and that's final." I didn't really need Roy to say that he wasn't going to come along, but Roy didn't say, "Don't make the film." He said, "I really hope this documentary turns out well. Good luck with it. It's a story that's worth telling." But I was just thinking about how bad I had felt, and for the first time, even though intellectually I knew Dick would say no, it was the first time I felt emotionally that he'd say no. I felt like parasitic paparazzi or something, hounding this old man who just wanted to be left alone.

I almost threatened to abandon the documentary right then and there, actually, even though we'd already been shooting for three days in London, because it just hit me so hard. But my line producer, Sarah Taylor, who was actually kind of my Roy Naisbitt on my own project, she was my right hand compadre on the thing, she said, "Well, you knew Dick was gonna say no. What are you moping about? Everyone else has said yes, and that's gotta be worth something." And she was totally right, so I just chomped down. I mean, what were we gonna do, just spend the next week and a half pretending that we were making a documentary in London? We were already there, so…

Anyway, fast forward to just a week ago, or two weeks ago, when it was really verified that (the Academy screening) was happening, I was obviously elated and excited, but it still strikes me as surreal. It's really weird that this happened, because everyone was so confident that he would never talk about it. It was always this untouchable subject in every master class or lecture he gave, whether because through the grapevine people knew not to mention it, or he would mention himself, "I'm not going to talk about this certain film, just to let you guys know in advance."

VINYARD: What's interesting is that, when he did eventually talk about it, it was with a great deal of nostalgia and affection. I don't think he mentioned the bond company or the recuts once. It wasn't the kind of cynical memory you'd expect.

KEVIN: I think he can't really talk about it from a legal standpoint, for one thing. But that's the other thing, like why dwell on the past? What Roy was getting at- I think that's why he was really annoyed and emphasized, "He still won't talk about it." Yeah, he lost his film, but the legacy is still there. To me, it doesn't even matter that he didn't finish it, because what does exist of it has permeated throughout the culture. Not just in terms of animation, but I think filmmaking in general. A lot of really ambitious, fantastical visual filmmaking. I wouldn't be surprised if Peter Jackson got ahold of that workprint before he made his LORD OF THE RINGS trilogy. And obviously, Spielberg saw it. There's that whole thing in one of the INDIANA JONES movies with that go-cart or whatever it is and the mines.

VINYARD: That's right!

KEVIN: And obviously it affected Disney (laughs), and all these guys are now working at Disney, or Pixar, or have started their own companies in U.K. and Europe by extension. With the internet, anybody, anywhere on the planet, whether they're in Palau or whatever, as long as they have an internet connection, can see what exists of this amazing, albeit unfinished and not without its flaws, art project.So yeah, I think you describe it really well. It was with a great deal of affection and, I think, excitement. He seemed genuinely relieved, and genuinely…it was a catharsis, talking about the old guys he learned from, Art, and Ken, and Roy, and all them. But on the other hand, there was a degree of caution. I was very surprised they had a Q & A, which I was told was not going to happen, but not surprised in the slightest that there were no questions taken from the audience, and I was not surprised that there was no reception. There were a thousand people, literally, who wanted to talk to him, and pretty much everybody, except for a few fanboys, knew not to, you know…he was happy, we were happy. It was such a catharis and a relif and excitement. It was sort of a world premiere of his film! It's really weird, 50 years since its conception, almost, it was sort of a world premiere. And yet it's still unfinished.

But that doesn't matter. It is A MOMENT IN TIME, which was a great subtitle, and I think that's really a good way of approaching it. It was a cautious sort of affection.

VINYARD: I think that's a great place to end.

KEVIN: Sorry about the rambling.

VINYARD: No, this has been great. Thanks for your time, and more than that, thanks for your documentary. You really put together this story that I've been trying to piece together in my mind since college, since I first heard about this, and it actually created a believable narrative out of what could've actually transpired, and somehow made the work even more outstanding and impressive in my mind, so thank you for that.

KEVIN: I appreciate that too, because I'm always doubting myself. It's all sort of self-destructive, as the documentary shows. But when I showed it in London, there were over 300 people there, sold-out show, and about 20 or 30 of those 300 or so were people who worked on the film. Everyone that I spoke to, at least, told me that it was a fair and accurate and engaging depiction of this story, and of this guy. Even Roy, for what it's worth, told me off the record, "You know, for someone who wasn't there and didn't know anything, you still got 95% right." And I said, "That's the best review I've heard yet."

VINYARD: That's an A!

KEVIN: Basically second-in-command on this amazing Titanic of a motion picture respected and appreciated it.

VINYARD: I hope the film gets into Richard Williams' hands and he gets to take a step back and see the story, but more than that, I hope the film gets out there in some sort of commercial sense so fans of the movie can actually see what happened.

KEVIN: I'll see what I can do. If it has to be leaked online, I'll be the one to do it, hopefully. We'll see what happens.

PERSISTENCE OF VISION - Trailer from Kevin Schreck on Vimeo.

"Persistence of Vision" Clip - "The Battle Sequence" from Kevin Schreck on Vimeo.

PERISISTENCE OF VISION is screening at the Bloor Hot Docs Cinema in Toronto every day this week through Thursday (1/16), save for Tuesday (buy tickets here). For updates on further screenings, or simply for more info on PERSISTENCE OF VISION, check out the film's Facebook page.

Check out my look at THE THIEF AND THE COBBLER and PERSISTENCE OF VISION.

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter