Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

This column will tackle an Oscar winner from each year starting with the inception of the Academy Awards in 1929. My goal is to highlight lesser-known films from throughout cinema history that were able pull down one (or more) of the Golden Statuettes that remain such an integral part of Hollywood lore. I will also take a close look at the actual element(s) that the film was given awards for, with my analysis on how they hold up with years (or decades) of cinematic history in the rearview since. This week, our subject is the 1931 winner for Best Cinematography, F.W. Murnau's TABU. Next Sunday, I'll be taking it easy for the holidays, and checking out the 2012 winner for Best Animated Short, LA MAISON EN PETITS CUBES.

For decades after its invention, the motion picture camera was a cumbersome device. It was heavy as all hell, prone to the usual flubs and glitches of any analog recording, and required very specific lighting and environmental settings to work properly. Forget about Steadicam, humbling crane shots, or Raimi-esque handheld craziness; until well after color and synced sound became mainstays of the cinematic language, just getting a static, tri-pod shot executed properly and in focus was somewhat of an achievement in and of itself.

This made shooting on location a very daunting proposition. You think of the nightmare location shoots like APOCALYPSE NOW or WATERWORLD, and how much time and money it cost to shoot in those conditions, and it's already mind-boggling; remove half a century of technology from the equation, and it sounds like crazy talk to take a film camera and use it anywhere other than the comfort, warmth, and safety of a Burbank production studio.

Not to say that it was an impossibility. There are shots of the Titanic setting off, for chrissakes! But other than newsreel footage or M.O.S. (dialogue-free) b-roll, location footage was generally looked at as an overly ballsy endeavor that should only be used if absolutely, positively necessary. Which makes the idea of F.W. Murnau attempting to make a feature-length dramatic film in French Polynesia using the locals as actors seem even crazier in retrospect than it would if he did it today.

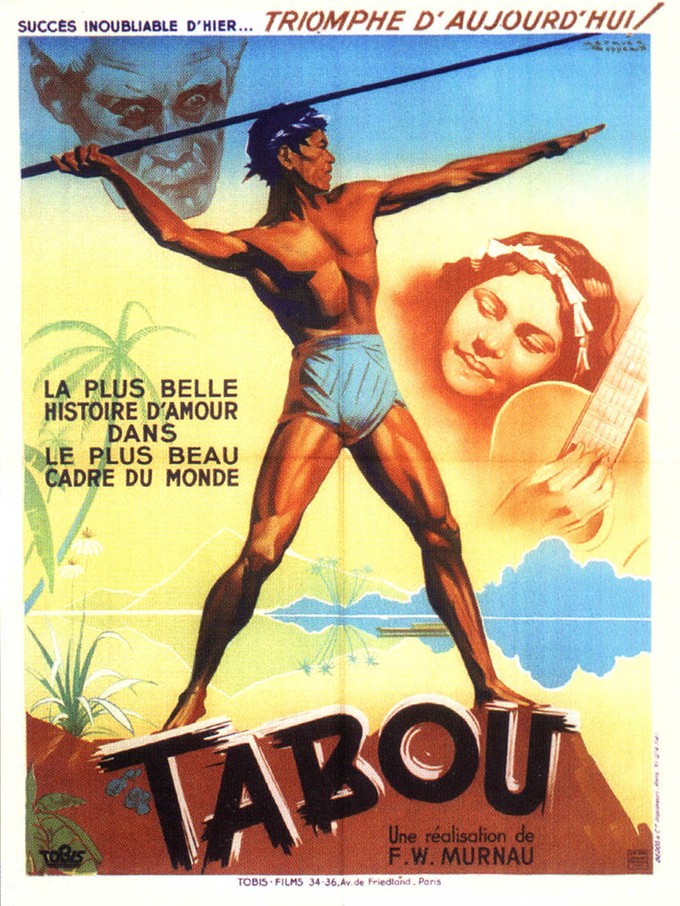

The guy had already had the kind of career countless filmmakers would try and replicate. Between THE LAST LAUGH, FAUST, SUNRISE, and, of course, NOSFERATU, Murnau left more of an impact on cinema in his 42 years on this earth than many workhorse directors who spent 50+ years in the industry. Then, in the last year of his life (he would die in March of '31 at the tragic age of 42), he teamed up with documentary filmmaker Robert J. Flaherty, whose NANOOK OF THE NORTH remains one of the most influential docs of all time, and set off to Bora Bora to make what would eventually be a romantic drama entitled TABU. The result won the film an Oscar for Best Cinematography and serves as an ambitious, hopeful swan song for one of the biggest names of silent era cinema.

Title Card:

FIRST CHAPTER

PARADISE

A title card reads:

A LAND OF ENCHANTMENT

REMOTE IN THE SOUTH SEAS

THE ISLAND OF BORA-BORA

STILL UNTOUCHED BY THE HAND

OF CIVILIZATION

The film opens with that shot on the poster above; a muscular French Polynesian native stands by the ocean and spears a fish out of the water, while the backdrop and framing make him look like an Olympic athlete. This is our hero, Matahi. After a few loving shots showing Matahi and his fellow fisherman frolicking in the gorgeous Bora Bora beachside, he encounters his lover, Reri. Matahi and Reri flirt and exchange headbands made out of seashells that almost look like Hawaiian leis, clearly a sign of affection. Without either party uttering a word of dialogue, it is obvious that their love is innocent, pure, and central to the narrative.

A large ship, obviously of western origin, arrives on the island, causing much fanfare. On the boat is an elder warrior, maybe 60-something, named Hitu. Hitu announces that a holy maiden, sacredly protected by the neighboring tribes, has died, and that none other than Reri has been chosen to replace her, due to her "holy blood". This means that, from that point on, "Man must not touch her or cast upon her the eye of desire, for in her honor rests the honor of all her people." She is marked "TABU", as in, "to break this TABU means death." Hitu is charged with delivering Reri to the island chief, while protecting Reri's chastity from any and all men.

As you can imagine, neither Reri or Matahi are all too thrilled at this development. While the rest of the island joyously dances and celebrates, they mope around with the knowledge that their love, however genuine, has just been compromised by fate. That night, they do what many young lovers would do in an unsupportive situation; they skidaddle, desperately canoeing into the sea, away from any tribes that would consider Reri holy, or anything other than just another islander. The tribesmen panic in her absence. A European in the area notes: The awful power of the Tabu will fall upon the Island, if Reri is not returned unharmed. If Hitu fails to bring her back, his life, as well as those of Matahi and Reri, will be sacrificed to appease the gods.

SECOND CHAPTER

PARADISE LOST

FLEEING THE VENGEANCE

OF THE TABU

THE GUILTY LOVERS

FOUGHT THEIR WAY

OVER LEAGUES OF OPEN SEA

SEEKING SOME ISLAND

OF THE PEARL TRADE

WHERE THE WHITE MAN RULES

AND THE OLD GODS ARE FORGOTTEN

By the time the pair lands on a shore, they're nearly dead of starvation and thirst. Luckily the locals take them in and help them recover. The Europeans in the area prize Matahi's diving skills, which allow them to procure more of the island's precious pearls, but take advantage of his abilities; to his people, money is a foreign entity, so he does not appreciate the value of the pearls he brings in. Nevertheless, the two assimilate nicely, and settle into their lives with the new tribe.

Soon, a local European receives a note that says that France, in an attempt to maintain peace among the natives, is offering a five-hundred franc reward for Reri's return to Bora Bora. He confronts the couple, but Matahi pays him off with the only pearl in his possession.

But wouldn't you know it, Hitu tracks them down, and tells Reri that she has three days to leave Matahi and return with him back to Bora Bora. If she doesn't comply, he'll be forced to kill Matahi and take her by force. She immediately plots their escape; a boat will take them to Papeete, the French Polynesian capital, in three days time, and will cost 130 francs, which the couple can barely afford. However, when the locals charge Matahi for "bills rendered," including the wine and food served to them at the celebrations, they are left dead broke, forcing Matahi to use his god-given talent for pearl diving in a last-ditch attempt to make the boat off the island. But there's the small matter of a man-hungry shark patrolling the most pearl-rich spot around…

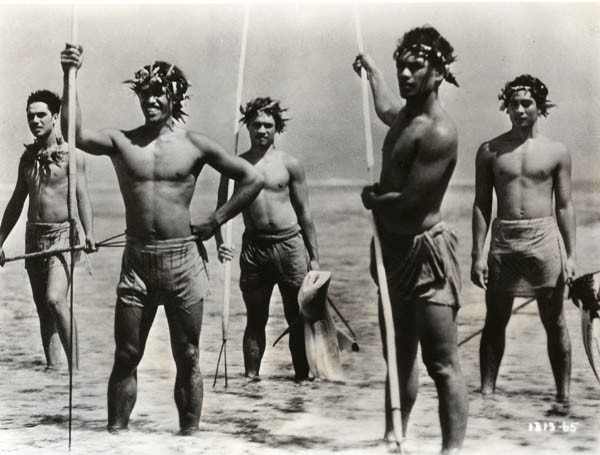

The first thing you notice when watching TABU is that nearly all of the characters in the film appear to be actual natives of Bora Bora, and not Hollywood actors. Sure enough, F.W. Murnau and co-director Robert J. Flaherty populated the film with locals to fill in the roles, including their leading lady, "Reri" (real name Anne Chevalier". The casting is a spit in the face of movies like THE GOOD EARTH and THE CONQUEROR, eschewing star power for authenticity, and somehow pulling a god's honest dramatic narrative out of the whole thing.

The effect of the casting is that it makes the film feel more legitimate, almost like a BARAKA-esque documentary; if these people really do stuff like this regularly, does it feel as artificial for them do to it at the behest of the filmmakers than it would if they recreated all of it with actors on a soundstage? The New York Times review of the film closes with, "These natives give remarkable performances. Their expressions and actions are as natural as the players in Russian pictures," (one wonders the need to compare the film to Russian cinema, but alas…). At its heart, the film is an unabashed love story, and if we didn't have stock in our leads, the whole thing would be a failure, but the principal cast members, with their weathered bodies and wonderful faces, help render the emotion of the plot into something as truly cinematic as any grand Hollywood romance.

The second thing that gets your attention, perhaps unsurprisingly, is the unbelievable location photography. When Flaherty called in budding cinematographer Floyd Crosby to help them on their troubled shoot, he almost undoubtedly had no idea that he was going to help the lad nab an Oscar for his first film credit, which would kick off a career that includes work on OKLAHOMA!, THE OLD MAN AND THE SEA, and Fred Zinnemann's HIGH NOON. But when camera problems necessitated a professional cameraman joining the two (aside from Murnau, Flaherty, and Crosby, the crew, like the cast, was made up of locals…yeah), Crosby traveled to Bora Bora to help shape the look of the film, which ended up earning the film its only Oscar nomination (and win).

The relationship with Flaherty and Murnau was increasingly strained as the production went on. Perhaps it is the inevitable result of such widely-acclaimed artists working on equal terms, but the pair's respective visions of the film clashed, and Flaherty ended up doing most of his work in the film development lab. Unsatisfied with Murnau's arrogant attitude and his "Hollywood" narrative stylings, Flaherty eventually sold his share of the film to Murnau for about a sixth of the film's budget. As co-director, his primary contribution to the film is shooting the opening scenes of Matahi and his buds hunting and playing around in the water, and those bits feel more like straight documentary filmmaking than anything else in the film. Everything aside from that opening scene is Crosby and Murnau.

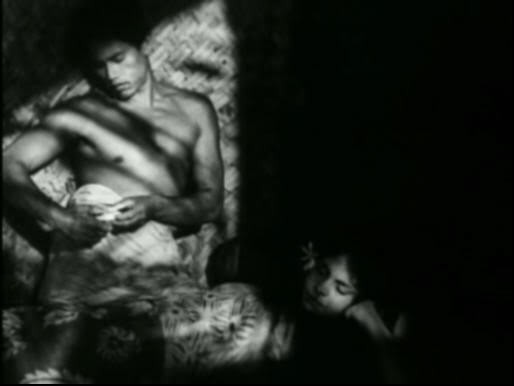

Man, what shots these two were able to land! And I'm not just talking about beautifully composed static shots of the marvelous scenery, although there's plenty of that in there too. I'm talking complicated camera movements, with perfectly executed background and foreground action, sometimes while floating on water following the characters. There's surprisingly well-covered underwater photography, including during a late action sequence with the shark. The group scenes are busy but clearly depicted, and we can always pick out Matahi, Reri, and Hitu out of the hubbub. And seemingly magically, given that they couldn't have had a huge amount of artificial lights, or professional grips to work said lights, there's arch lighting and shadowplay in there that may not be as cutting and revelatory as Murnau's work in German expressionism, but still makes a deep impression.

I really don't know how they were able to get a lot of this stuff without a professional Hollywood crew, especially once NANOOK OF THE NORTH director Flaherty was basically off of the show. But the cinematography really does become one of the characters, as crucial to the film's emotional resonance as the central romance. It helps paint the picture of this idyllic island, this living, breathing environment where the manmade obstructions that were in the process of creating the modern world are unpresent and barely imaginable. I suppose the photography and the native cast are what led to the film being called a "docudrama", or "docufiction", but I think the narrative is too pronouned and crucial for that. What they do end up doing is depicting this not wholly original narrative as something signature, foreign, and remarkably genuine, even despite the various cinematic tricks Murnau and Crosby had to utilize for some of their setups (for example, creating an artificial moon for the nighttime shots).

One shot is so impressive that I have to make specific mention of it here. When the European boat first arrives at Bora Bora at the outset, there is what appears to be a single shot of Matahi that is intercut with other footage, but seems to have been initially filmed as an unbroken take. It starts as a shot from behind Matahi, clearly taken while the actor was actually navigating the cameraman around on his canoe, as he paddles his craft closer to the larger boat. We see his back in the foreground, while the majestic French sailboat lingers in the distance. As Matahi's boat gets closer, his fellow islanders approach the European vessel. A young boy calls Matahi back to shore, and he turns his body around and starts paddling in the opposite direction, while the other islanders swarm the sailboat in the same shot. The progression of the shot, starting with Matahi paddling away from the camera towards the boat and ending with him facing the camera while his people paddle in the opposite direction, is truly striking, and is far more cinematic, dramatic, and just downright impressive than it would've been if it were shot simpler, and from a distance, in true documentary fashion.

While I don't agree that the story's too "Hollywood" to be palatable, I do have problems with the western-influenced elements of its subtext. The narrative has Matahi and Reri living in bliss once they've escaped their tribe, but forces them into desperation and despair when Matahi fails to grasp the concept of money and blows their chance at keeping their fate at bay. While one may argue that the critique of western living, with its confounded senses of capitalism and unjustified superiority, may supersede any condescending attitudes towards native life, there remains the fact that it's the local belief that Reri is, in fact, "Tabu" that causes the central conflict in the first place.

There's no question that we're supposed to side with Matahi and Reri on their quest to find true love and happiness together. It's a narrative as old as storytelling itself, the forbidden, doomed love, and the tragic lengths lovers will go to protect that love. So when tribal tradition, and not the western settlers, prove to be the reason that Matahi and Reri can't frolick in the gorgeous Bora Bora beachside for all eternity, it is their primitive adherence to religion, not the white man's adoption of currency as the primary form of interaction, that ends up to blame. Sure, if the Frenchmen (and the Chinese shopkeeper who notifies them of the impending boat to Papeete) were a little more understanding and a little less greedy, our couple would get away from Hitu's speartip with hardly any difficulty, but it would still be the threat created by the islanders that they'd be running from.

The metaphor of the man-eating shark being "Tabu" as well, as trite as it seems, is more effective. When the Europeans discover that the prime area for pearl diving is being patroled by a shark, they mark it with the a sign saying "TABU", decreeing it as off-limits as Reri's virginity. SPOILER ALERT*****In the final reels, when Matahi desperately plunders the area for loose pearls, he is forced to grapple with the shark head-on, and, through sheer perseverance, succeeds in stabbing the shark to death and swimming away with his loot. The two spend much of the film's screentime attempting to escape the vengeance of the Tabu, but they are putting off the inevitable; they will have to face the beast eventually, and it is only after they do that they have a true shot at happiness. Perhaps the masterstroke is that HEAVY SPOILER ALERT***** Matahi discovers that Reri has willingly left with Hitu, and he drowns while pursuing the duo. It creates a bittersweet ending that is a testament to their love, but highlights how utterly doomed it was from the moment she became Tabu, even given the lengths they'd go to protect it*****END SPOILER. It's not the thickest, least-decipherable subtext in the world, but it adds dramatic weight to the highly visual, atmospheric impact of the film.

Is the film a remarkable cinematic achievement? In my opinion, it absolutely is. Do I think the film was snubbed in the other categories? Not necessarily. I haven't seen CIMARRON, the epic western that took home three Oscars that night in '31 (and was the first film to take more than two awards at all), including Best Picture, but it's reputation precedes it. It's massive scope (with a budget nearly 10 times that of TABU's paltry $150k price tag) and Americana-friendly plot was almost certainly more eye-catching and viscerally impressive than the "newsreel-y" vibe that TABU may have given off.

In fact, like APOCALYPTO or even CHILDREN OF MEN 70+ years later, the production is so technically impressive that it's easy to blow off the rest of the film's achievements. While the story, staging, and editing are well-executed, and nothing to be scoffed at, the overall feeling the film gives off is less "That's a classic piece of cinema," than "Wow, how did they get this together in 1931?!" The Romeo and Juliet-by-way-of-French-Polynesian-tribal-dogma plotline is rendered effective through its presentation, but in and of itself it is nothing truly original. Murnau's goal, or at least one of them, was to shoot a Hollywood film with an all-native cast and crew, and in that sense he succeeded. The film feels like a big movie with authenticity burned into its bones, but one of the sacrifices that Murnau made, either willingly or unconsciously, is that "big movies" tend to have fairly traditional narratives. Not a knock, just an observation, but my thinking is that if he'd gone more experimental and abstract in his writing, the film would be better remembered (and, perhaps, even more influential) than it has been over the years.

While he's ostensibly one of the legends of the early days of cinema, Murnau never quite got a fair shake in terms of acclaim, and the Oscars awarded to his films were given to others (SUNRISE: A SONG OF TWO HUMANS won its producer, William Fox, "Best Picture, Unique and Artistic Production"). Tragically, Murnau's 14 year-old chauffeur killed him by driving his car into a pole a week before TABU premiered in New York City. Would he have ever been able to top NOSFERATU, THE LAST LAUGH, FAUST, SUNRISE, and TABU? We'll never know. From what we do know, we can acknowledge that the guy was one of the trailblazing voices out of German expressionism, that he was willing to take crazy chances just as the studio system was taking ahold of the industry, and, as TABU certainly emphasizes, he cared more about pushing the medium, transmitting his vision, and achieving greatness than he did his relationships with others and, maybe, his own life.

PREVIOUS ENTRIES:

UNDERWORLD (1927): Best Writing (Original Story)

SEARCHING FOR SUGAR MAN (2012): Best Documentary

THE BROADWAY MELODY (1929): Best Picture

THE IRON LADY (2011): Best Actress

THE BIG HOUSE (1930): Best Writing, Best Sound Recording

IN A BETTER WORLD (2010): Best Foreign Language Film

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter