Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

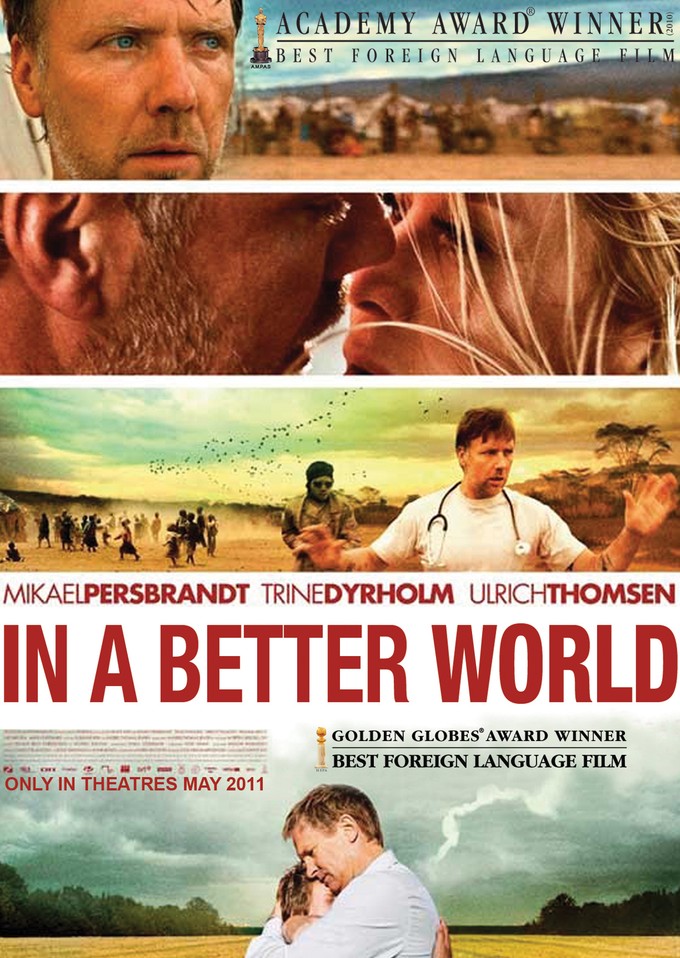

This column will tackle an Oscar winner from each year starting with the inception of the Academy Awards in 1929. My goal is to highlight lesser-known films from throughout cinema history that were able pull down one (or more) of the Golden Statuettes that remain such an integral part of Hollywood lore. I will also take a close look at the actual element(s) that the film was given awards for, with my analysis on how they hold up with years (or decades) of cinematic history in the rearview since. Today, I'm taking a look at at 2011's winner for Best Foreign Language Film, Susan Bier's IN A BETTER WORLD. Next week, this column will discuss F.W. Murnau's TABU, the 1931 winner for Best Cinematography.

I don't think I'm taking a huge gamble in assuming that many of you (like myself) had some problems growing up. Maybe I'm being presumptuous, but being the kind of kid who loves movies, comics, video games, anime, RPGs, or general geekery doesn't necessarily lend itself to being a take-no-shit "alpha". There are definitely exceptions, but generally, carrying a torch for that stuff and wearing it on your sleeve like a badge of honor tends to put out a kind of scent that predatory adolescents sniff out like lions looking for weak antelope. It's a depressing thought; one that, more often than any of us would like, turns out to be true.

Another trend: that person that shows up and seems to take charge in a way that you've never really thought possible. The kind of person that, whether they share your beliefs or not, is willing to do what is necessary to assert themselves and make sure that they aren't the kind of asshole magnet an outspoken young geek sometimes tends to be. When they take you under their wing, it's like taking a step into a brand new world, the kind of place where you're allowed to be who you want to be without the fear of alienation or loneliness. After all, if this person likes you, then how shameful can your interests really be?

At it's heart, IN A BETTER WORLD is about this kind of relationship, the effect it has on the two lost boys who find each other, and the ramifications of their new friendship. It examines what it means to stand your ground, and the collateral damage that fighting back against aggressors and bullies can sometimes cause. It's about maintaining your humanity when your life seems broken and unresolvable, and the random events that happen to bring us together, as well as those that split us apart. It's very much a story about life and love in the modern world, but done in such a way that it feels like an actual story, rather than a statement of its themes.

Plus, it shows how easy it is to whip up your own pipe bombs.

The story starts in Sudan, where a Swede named Anton serves as a doctor for the local villagers. He immediately shows himself to be a sympathetic and humane fellow, with the full trust and cooperation of the locals. After treating a viciously mutilated young woman, he learns of her assailant; a neighboring psychopath who gets his kicks cutting open pregnant girls after making bets on what sex her unborn fetus will be. He's wordlessly disgusted.

We then meet Christian, a sharp young boy reading Hans Christian Anderson's The Nightingale at his mother's funeral. His father, Claus, is proud of his son, and announces his plans to take him and move in with his own mother in Denmark. Christian is clearly haunted by his mother's death, but is shellshocked and pounding through it with a stone-faced, existential glare. Claus, understandably, is more visibly distraught, but keeps it together for the sake of his kid.

On his first day at his new school, Christian is paired off with a young boy named Elias who is regularly teased and harassed by bullies. He tries to stick up for Elias, but a tall blonde jerk swiftly throws a basketball in his face, bleeding his nose. His dad is concerned, but he blows him off. That night, Elias's dad comes back to town to be around his estranged wife and son; whaddyaknow, it's the Swedish doctor Anton, who flies back and forth between his family in Denmark and his duties in Sudan.

The next day, while the basketball-throwing asshole is getting ready to accost Elias in the bathroom, Christian takes a bat and beats the ever loving shit out of the little punk, before putting a knife to his throat and threatening to kill him if he doesn't cut out his Nazi youth routine. Elias gladly helps Christian stash the knife, telling him he'll get kicked out of school (an immediate sign of endearment; he finally has a pal, and isn't gonna see him get swiftly expelled), and when the incident blows over, Christian lets him keep the blade for himself. They quickly become close buds.

One day, the two are with Anton when Elias' little brother has an altercation with another boy on a swingset. Anton pulls the two kids (both barely past toddlerhood) away from each other, and the other boy's dad gets miffed and gets right up in his face. The harsh, brutish man gives Anton grief for laying a hand on his kid, slapping him multiple times in the face right in front of the boys. Christian protests; obviously, he's not okay with that kind of one-sided abuse, but Anton insists that they let bygones be bygones.

The next day, after Elias questions his old man's reaction, Anton takes the three boys to confront the douchey father that slapped him, telling him that he wants to show them that he's "a fucking idiot who gets a strange satisfaction from believing (he) has power over other people." The offended, insecure man responds by slapping him around again, calling him a "poof", and telling him to go back to Sweden; again, Anton insists that it "doesn't really hurt", and leaves peacefully. He flies back to Sudan, where the mutilating madman he was previously informed of suddenly drives up in a jeep with a badly infected leg wound, begging for care. Despite the pleadings of the villagers, who, more than being afraid, cannot imagine helping such a clearly evil individual, Anton obliges and saves the leg.

The boys, particularly Christian, can't sit with Anton's passivity towards the guy that hit him, and swear revenge on his assailant. They concoct a scheme to take gunpowder from some old fireworks and use them to concoct some pipe bombs for the purpose of blowing up the slap-happy asshole's van. Elias is hesitant at first, but after his mother finds Christian's knife, creating a distance between the two boys (at that age, letting your buddy get caught is almost the same thing as ratting them out yourself), Elias jumps onboard the plan feet-first. What happens afterward creates a shockwave through the lives of everyone involved, making Claus, Anton, and especially Christian deeply reflect on their stances towards violence, and how the situation was able to snowball into a life-threatening and life-changing scenario.

If you'd listed the films nominated for the Best Foreign Language Oscar back in 2011, including Alejandro Gonzales Inarritu's BIUTIFUL, Denis Villeneuve's INCENDIES, and the Greek film DOGTOOTH, IN A BETTER WORLD would not be my first guess as to what eventually took home the award. If I'm to be fully frank, even though I've watched every Oscar ceremony since TITANIC swept the awards in '98, I'd never once taken note of the film, nor do I remember it being any sort of critical darling (meanwhile, I've seen DOGTOOTH and BIUTIFUL referenced more regularly since).

More interestingly, even though the film was directed by Susanne Bier, whose AFTER THE WEDDING (also nominated for Best Foreign Language film) I had seen in film school several years before her following film was honored by the Academy, I had no idea that she had ever actually landed Oscar gold. Until I looked up the Oscar winners from the 2012 ceremony for this column, I had no idea what IN A BETTER WORLD was, who directed it, what it was about, or why I should care about it's existence.

Now having seen the film, I have somewhat of an idea of how this came about. The film is similar to AFTER THE WEDDING in several ways (including some I'll discuss later), including being a fairly low-key domestic parable, albeit shot and executed in a highly dramatic fashion. It's not as gut-wrenchingly memorable as this year's winner, AMOUR, or as intimately insightful as the previous winner, A SEPARATION. What it is is a deft, well-acted drama that deals with family, friendship, violence, and redemption, albeit in such a way that the events, however coincidental (and sometimes overly so), feel like a period of time in the lives of these characters rather than the constructs of a paid screenwriter.

However, I don't consider the film to be an unabashed success the way I do the category's latter winners. There are a ton of subplots in this thing, and while Bier and co-writer Anders Thomas Jensen strive to tie them all together, in the end, I feel that the film is lesser than the sum of its parts. It sort of feels like one of those movies, like SOUTHLAND TALES, KINGDOM OF HEAVEN, or METROPOLIS where the edited versions leave out crucial information about certain events or characters that are necessary for the coherence of the narrative. You know that feeling, where you're watching a director's cut, and you think, "Wait, that's why that character did that? Now it actually makes sense!" I could very easily imagine that happening with a different edit of this movie.

For example, the character of Claus, played by THE CELEBRATION's Ulrich Thomsen, is set up to be a major player in the plot early on. His strained relationship with his son, his grief over his wife, and his struggle to maintain dignity while picking up the pieces of his life are introduced with as much weight as anything in the picture. When he meets Elias's mom, Marianne (played by Thomsen's CELEBRATION co-star Trine Dyrholm), there is evidence of an immediate attraction, noted by Christian, who accuses his father of wanting to "kiss her." There's even a scene that cross-cuts between Claus and Marianne driving their respective sons home that visually creates a distinct parallel of the two, hinting that they are just as appropriate for each other as Elias and Christian.

However, there's no follow-up to this subplot, and Claus is all but forgotten in the final reels, while Anton and Marianne's woes are on full display. According to IMDB, there was originally more footage of Claus and Marianne that had to be jettisoned from the film because of "too many story lines." Which makes sense; the film, ostensibly about the two boys' friendship, has an abundance of side plots that, while vaguely connected to the film's themes, eat up a lot of screentime. I can understand the need to trim the fat in order to highlight the central plot of the film, even at the cost of a strong, tightly-wound performance by Thomsen.

But the finished film still sets aside a ton of time to deal with Anton's efforts in Sudan, which have way less to do with what's going on in Denmark than the possibility of Claus and Marianne getting together. The gorgeously photographed stuff in the Sudanese desert may look great, and plays realistically and without even a smidge of "white man's burden" condescension (it's clear that his primary distinction from the local population is his Western medical degree), but it is, in the end, pretty much filler. The visually and thematically extreme content with the murderous thug and his infected leg may tie into the notions of impotent bullies and their inevitable downfall, but it is otherwise completely isolated from the plot developments in Denmark. The climax of this subplot is overblown and grandiose, and feels like the ending of a completely different movie, although you could make the argument that it sets the stage for Anton's emotional state in the third act. Nonetheless, I don't even think Anton mentions the events that transpire out there to either of the boys, including during the heart-to-hearts he has with them towards the film's end, making it all seem kind of background and perfunctory.

In many ways, this subplot, and the character of Anton as a whole, seem directly lifted from Bier's AFTER THE WEDDING, where Mads Mikkelsen played a Dane selflessly working his butt off in an impoverished Bombay orphanage. That character's child also plays a huge part in his development, and inspires him to spend more time with his kid, rather than with the foreigners he was previously so devoted to caring for (interestingly enough, the actor who plays Elias, Anton's son, bears a striking resemblance to a young Mikkelsen). There, his work played a central role in the narrative, where Mads' Jacob was conflicted between resuming his duties in India and becoming a father to his daughter for the first time since her birth. Here, Anton's African exploits feel more like an excuse to lovingly photograph the Sudanese desert (which, perhaps expectedly, really does look quite striking), and to add some foreign spice to complement the film's otherwise humdrum Danish locales.

But you know what works like friggin' gangbusters in the movie? Pretty much everything having to do with Elias and Christian's burgeoning friendship. As you can deduce from my intro, this element really connected with me on an emotional level, and it really is representative of everything that is truly noteworthy about this film. The two boys, played by William Johnk Juels Nielsen (as Christian) and Markus Rygaard (wonderfully endearing as the weaker, innocent Elias), are depicted with a great deal of honesty, humor, and pathos, easily on the level of something like STAND BY ME.

Christian is one of those kids with maybe a little too much brains and balls for his own good. He is intelligent and, thankfully, mature enough to refrain from constantly crying like an infant over the recent death of his mother, but not worldly enough to understand his unavoidable subconscious reaction to it. He may have beat up bullies, built pipe bombs, and screamed at his father many times before his mom passed, but almost certainly not with the vengeful furor he exhibits after the fact. Even though it is Christian's father, and not his own, who suffers humiliation at the hands of the dickface mechanic whose van he blows up, he takes up the cause of getting revenge on the loser like he's Shosanna Dreyfus staring at the notion of incinerating the Nazis that cost her her family (although, like in that film's ironic twist, he is powerless to strike back against the actual cause of her demise, in this case cancer). When he accuses his dad of being a selfish asshole who "wanted" his mom to die, he lacks the emotional restraint to understand why Claus would wish the end for his suffering, deathly ill wife, but he has the nuts to challenge his grieving father as he breaks down in front of him. This kid is either going to get himself killed, or become a trailblazing success; there doesn't seem to be a middle ground for him, and his mother's passing is the fuse to his aggressive behavior that's just waiting to get lit, which, of course, it does.

Maybe it's Christian's need for someone in as much emotional pain as he that inspires him to befriend Elias, or maybe it's simply the knowledge that he can easily take the kid under his wing, but there's no question as to what attracts Elias to him. Poor Elias, dubbed "ratface" by his peers due to his braces (a nice touch added when Rygaard showed up to set with them on), is so used to being bullied and bossed around that he's barely surprised when he discovers that the air from his bike tires has been maliciously released; "They took the valves as well. They always do. I'll just walk home. It's okay." He can't even respond well to some good-natured ribbing from his mother, lashing out at her the way he couldn't against the schoolboys who actually aimed to harm him.

When Elias sees Christian beat up and hold a knife to a bully getting ready to accost him, it creates an almost physiological attraction to his protector. Between taking a basketball to the face while defending him and viciously striking a dude getting ready to beat him up, wouldn't it make sense for Elias to follow Christian around in awe afterwards? The scene of Elias' mom finding the knife that he's hiding for Christian is heartbreaking; as Rygaard plays it, he is fully aware that her discovery can cost him his friendship with Christian (which it very nearly does), and he is willing to lie to her, point blank, in the face of all logic in a desperate attempt to wipe the event from existence. It's not long before we realize that this devotion to Christian is going to cause Elias emotional, and maybe even physical, harm, but we don't care. The notion of their friendship ending, leaving Elias to go back to being a defenseless, emotionally trampled victim, seems like a much more frightening and painful outcome.

Had the rest of the film had as much of an emotional charge as watching the relationship of Elias and Christian develop, fall apart, and re-congeal repeatedly, the film could've been a no-question lock for that year's Best Foreign Language award. Unfortunately, the over-reaching narrative, a preference for thematic coherence over character development, and some crucial elements left on the cutting room floor hinder the film, and keep it from living up to its best moments. And it ain't just me. Roger Ebert gave the film two-and-a-half stars, noting that, "The African events in particular don't fit organically into the rest of the film, playing more like a contrived contrast." A.O. Scott of the New York Times decries the film's moments of heightened drama as feeling "just a little too easy: a better movie might have let in more of the messiness of the world as it is. This one falls into cheap manipulation…"

If this film had won (or even been nominated) for Best Picture, rather than Best Foreign, it's faults would be even more glaring; say what you will about BIUTIFUL and DOGTOOTH, but to rank this film against the likes of THE ARTIST, MIDNIGHT IN PARIS, HUGO, or THE TREE OF LIFE would have almost certainly caused an uproar (although it's easy to forget that EXTREMELY LOUD & INCREDIBLY CLOSE secured a nom, perhaps due to some savvy campaigning by producer Scott Rudin). Perhaps it's because we are more forgiving of melodramatic manipulation when it's in a foreign language, or maybe it was as simple as the Academy giving Susanne Bier the award more for AFTER THE WEDDING (although even PAN'S LABYRINTH failed to beat Florian Henckel von Donnersmark's incredible THE LIVES OF OTHERS that year) than for the film actually being nominated.

Nevertheless, IN A BETTER WORLD will always be the 2011 winner for Best Foreign Language Film, and will be held to that standard as long as the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences maintains it's relevance. It is no masterpiece, nor does it live up to the heights of the various collaborators' previous Danish films THE CELEBRATION and AFTER THE WEDDING. However, it has a deeply touching, remarkably human, and surprisingly brutal friendship between two struggling 12-year-olds at its core that rivals any portrayal of that stage of adolescence I've ever seen. Too bad much of what surrounds that core ends up coming off as window dressing.

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter