Born and raised in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia, Scott Cooper witnessed first-hand the slow, sad decline of America's Rust Belt. He saw how proud, hard-working people were gradually put out of work through no fault of their own. They were casualties of automation and globalization, and when their jobs disappeared, they scrambled to find ways to support their families. The options were rarely attractive, and, in some cases, on the wrong side of the law. This is what desperation does to people.

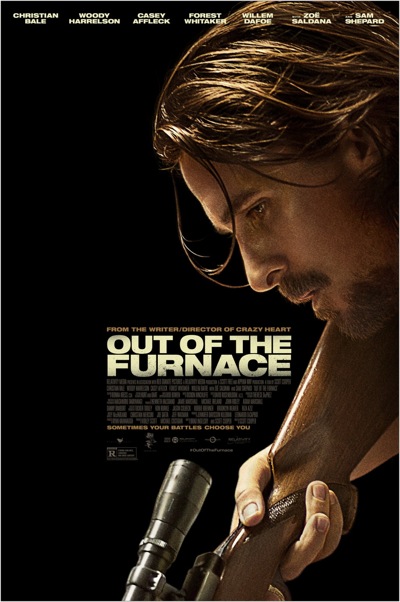

This world is rarely depicted with authenticity in Hollywood movies, which makes Cooper's OUT OF THE FURNACE something of a minor miracle. It's a gorgeously shot, star-studded feature that immerses the viewer in a region most of the country would prefer to ignore. The characters in his film are dealing with no-win situations: Russell Baze (Christian Bale) is struggling to earn a living after serving time for a fatal DUI accident, while his brother, Rodney (Casey Affleck), competes in brutal bare-knuckle fighting contests to make ends meet. The only character doing well is the most vicious: an Appalachian drug kingpin named Harlan DeGroat (Woody Harrelson). And when Rodney lands on Harlan's bad side, Russell is forced to hunt him down.

OUT OF THE FURNACE is Cooper's follow up to his critically-acclaimed CRAZY HEART, which won Jeff Bridges a well-deserved Oscar for Best Actor. An actor himself, Cooper has acquired a reputation as a talented director of performers, and he has solidified that rep with this film. Bale, Affleck, Harrelson and a murderer's row of supporting actors including Willem Dafoe, Sam Shepard and Forest Whittaker all disappear into their roles. And they are all beautifully shot by world-class cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi, who captures the run-down feel of the Rust Belt better than anyone since Vilmos Zsigmond in THE DEER HUNTER.

There are unmistakable echoes of THE DEER HUNTER in OUT OF THE FURNACE, but Cooper has brought a great deal of his own upbringing to the film. When I chatted with him at the film's Los Angeles press day, he made it clear that this is a deeply personal movie - his chance to accurately represent a world too often caricatured by Hollywood. In the below interview, we discuss the inspiration for the film, how he managed to assemble such an amazing cast and where he'd like to take his career from here.

Mr. Beaks: Having grown up in this world, how much of this story were you writing in your youth?

Scott Cooper: A great deal. Most of it comes from real life and personal experience, and you try as best you can to weave that through the narrative truthfully and respectfully. It makes it all the more harrowing when you actually put it to celluloid and release it to the world, but I think when you make personal films it seems like the actors really gain a sense of strength and conviction. They really want to do the best work they can do to help you realize the story. I've only made two films and both are personal, so I wouldn't know otherwise, but it seems that way. For better or for worse, from fade-in to fade-to-black, it was everything I'd hoped for and more.

Beaks: When it comes to Hollywood attempting to depict this world that you know so well, how defensive do you get?

Cooper: Very defensive. Too many times, people pejoratively call them the "fly-over states", so the people from the Appalachian region are typically exaggerated. They're stereotypes. But these are all fully fleshed-out, three-dimensional people who are flawed and complex, but god-fearing and faithful. They're true humans, and too often I see them depicted in ways that aren't truthful. It's upsetting.

Beaks: There are several interesting milieus here that aren't commonly depicted. The one that fascinates me most is the subculture of bare-knuckle fighting. I know it exists.

Cooper: Oh, they exist. They exist in the basements of Manhattan.

Beaks: What was research into that world like?

Cooper: Very interesting. Most people don't realize that it exists, but it exists among people and between people that would surprise you. They're young investment bankers looking for thrills, or young models, or people who live in steel country, or people in the Deep South who work in a paper plant. You also see it in forms of dog fighting and cockfighting, and all of these types of violent and pugilistic ways that people express themselves. People think that it's mythological, but it is all too real. In this case, it's a man who has fought for his country for twelve years, and has only been taught to fight. That's the only thing he knows, and it's the only way he can survive when he comes back and finds the economy in ruins. Unfortunately, this is a man who ironically did not die in Fallujah and Tikrit, but dies in the hills of Appalachia.

Beaks: You've been hitting home runs casting-wise with your films. I look at this cast, and I say, "If these weren't your first choices, I'd really like to see who your first choices were."

Cooper: Oh, they were first choices.

Beaks: How do you attract this kind of talent? Obviously, the script gets them, but is there any kind of wooing process?

Cooper: That's a difficult question to answer. It's probably better for the actors to answer that, but this I know: as an actor who had a very unremarkable career, who longed to play the parts that Robert De Niro and John Cazale and Gene Hackman and Al Pacino played, we know that in an era of sequels and hit movies and comic books, those characters do not exist. So when an actor is presented with a world that they yearn to be in, or that hearkens back to a richer and deeper era, they want to be in that film. It's risky and dangerous.

I wrote CRAZY HEART for Jeff Bridges. I didn't even know him, and I was so fortunate to get him. I wrote [OUT OF THE FURNACE] for Christian Bale, and was fortunate enough to get him. It's daunting, because you just know somebody's going to tell you no. Casey's been one of my favorite actors. He's one of the best actors of our generation, and he's very underappreciated and underused because, quite frankly, he turns everybody down. He could work more frequently than he does. But once I had Christian, if I couldn't get Casey I wasn't going to make the movie. We ultimately prevailed. He loved the script, and wanted to do the movie.. Then I turned to Woody. We've known Woody for, what, twenty, twenty-five years dating back to CHEERS? You know Woody is someone who's very kind and trusting and funny, and I wanted to see a whole different side of Woody. I wanted to see it in the opening frames of the film, so you realize you're in for a real ride. It's almost like JAWS in the opening. You know anytime this man is around, this bedrock of menace will just kind of hover over the scene. I'd always admired Forest Whitaker, and Sam Shepard is a hero of mine. And Willem Dafoe is so good. He's so great in the film. And then there's Zoe Saldana, whose work I wasn't too familiar with, but she had a humanity that I could see. I spent time with her, and I knew she could go to these depths and bring a real femininity to a very masculine world. That was my casting process. It was very direct.

Beaks: For someone who studied theater and now is a writer, I imagine that getting Sam Shepard to be in your film must've been a personal triumph.

Cooper: For a man who's had some great titles for his plays, when I picked up the phone and heard it was Sam Shepard, he said, "This is one of the best titles I've heard for a film in a very long time." Terrence Malick said that as well. Then you say to yourself, "We're onto something here." Sam loved the writing, which, again, means so much to you. He said, "You don't spell it out for people. There's ambiguity, it's subtle... I'm absolutely in. When do we start?" To hear Sam Shepard say that about your work, for a guy whose plays I've read and re-read, his memoirs and interviews, and I love his work as an actor... it's just a privilege.

Beaks: You mentioned De Niro and Cazale, which naturally brings us to THE DEER HUNTER. That's a film you echo in some very interesting ways.

Cooper: You can't help but think of that because of the location. It deals with war, this deals with war. It deals with war in a very overt manner, this one deals with it in a much more subtle way. Anytime as a second-time filmmaker that you use a movie like that as a touchstone, it's tricky. That's a masterpiece. It's one of the great films of the last fifty years. You can only fall short of that. So you just try to tell personal stories and use these as influences. I'm not Michael Cimino, and very few people are. That's an extraordinary piece of filmmaking. So if people see echoes of it in a positive way, I'll take it.

Beaks: Visually, this film is incredibly striking.

Cooper: [Masanobu Takayanagi] is a wonderful cinematographer.

Beaks: It's your second time through as a filmmaker. What's your relationship like with the cinematographer?

Cooper: It's critical.

Beaks: How did you guys figure out the color palette?

Cooper: I had admired Masa's work from WARRIOR and THE GREY. When I asked to meet with him, I brought maybe 300 photographs that I had bound. Robert Frank, Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans... there's a Walker Evans photograph of a cross on a tombstone, and beyond it are these smokestacks reaching to the sky like the arms of god in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania in the 1930s. That was a real touchstone for me. I said to Masa, "I really want to shoot this anamorphically, but I don't want it to be sumptuous in any way. I want it to be painterly in a realistic fashion." He understood completely that color palettes of rust and muted greens and leaden skies highlighted by silvers, greens and blues, which would allow the blood that we experience with the deer and through Casey Affleck and Woody Harrelson's characters to really feel significant. It would also paint the world in a way I see it through my lens cinematically. I had a very prominent director see the film last night, and he said it was one of the best looking films he's seen in years. That's a testament to Masa's incredible work. This particular director wanted to race to hire Masa. People really embraced CRAZY HEART, but I haven't had this type of embracing from the people who most matter to me, whether it's Jeff Bridges or Robert Duvall or my cinematic hero directors from the 1970s, whose work I've admired and stolen from and curated from. For them to say the things they have, if I never read a piece of film criticism, I will have what they have said for the rest of my life and take that to my grave.

Beaks: That's the trick: being able to pull off that '70s aesthetic and style of storytelling. There's ambiguity. You're not just giving the audience what they want. It's hard to make that kind of film nowadays.

Cooper: I'm not resorting to tropes or formulas. If I were, Casey Affleck would be dead on page ten, and Christian Bale would be avenging his death for the next ninety minutes. When people don't get that, they blanche at it - like these bloggers who feel like they're screenwriters. But when William Friedkin tells you, a man who's made masterpiece after masterpiece, or Michael Mann, you say to yourself, "Okay, this risk that I took is all worth it." As opposed to people... I find a great deal of the internet to be mean-spirited. People hide behind anonymity. They're cynical and bitter. Perhaps that's a result of how we all feel as a nation after 9/11, a sort of post-traumatic stress disorder or shock, as Steven Soderbergh recently said. Everybody wants their movies to be uplifting and palatable and digestible. I don't know. The internet has become so mean-spirited that it can really fill you with bitterness and cynicism and angst, so I stay away from that. I would rather hear what Michael or Duvall or Jeff or Friedkin, people who actually make movies, have to say.

Beaks: You have access to some of the greatest film artists of our time.

Cooper: Right. It's tough, man. It's harrowing to put out a personal film and know it's going to be divisive. I don't know if people are seeking perfection - because all movies are flawed. This movie is flawed, but it's as truthful as I could make it. It's the second film I've made, and I didn't have the luxury of toiling away in obscurity before you really get your sea legs.

Beaks: The actors take so many risks in this film. They're not afraid to go really big. I think of the moment where Casey explodes at Christian in the kitchen. He just unleashes a sort of primal scream.

Cooper: That's not something Casey is sitting in his hotel room thinking, "I'm going to do that." That's living in the moment and releasing a great deal of rage and angst and all of the things he's seen as a soldier and all of the research he's done. You and I can't even imagine the things these soldiers see. He's releasing that. That's not something you can plan as a director or an actor, and when you see it... I'm sitting right next to the lens, and Christian Bale is taking that and tears are rolling down his face: that's as fine as screen acting gets. That's the type of moment where you turn to Masa and say, "Jesus, I hope you got that." And he looks at you and says, "I got it." You don't go for a second take there. At that point, it becomes premeditated.

Beaks: The issue of takes is always interesting to me. I was interviewing people from INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS yesterday, and they said the Coens don't like to do more than five, maybe six takes.

Cooper: Those guys are masters.

Beaks: Absolutely. And they like to move. As an actor-turned-director, how do you feel about that? I know there are a lot of actors who like to do take after take, who say "I want to try something else." Where is the line for you?

Cooper: I always allow them to take risks. If they really feel like they need or want to do a couple more takes and try to find something new? Absolutely. No question. But I don't typically rehearse. I like to shoot rehearsals, so it's a live wire. You're looking for spontaneity, and you never want to say, "God, I wish I'd shot that!" We do so much investigative text-work prior to shooting, that I know they understand who these characters are. I don't like to wear my actors out. I have great, great respect for actors. I won't move on until I get something, but when you've got this cast, you get what you need and more.

Beaks: You seem to have hit upon a time and a place that you really understand with your first two films. Are you looking to have a series of films that document life in these regions?

Cooper: I've written a piece that chronicles the Depression, another time of economic and racial turmoil, that spans from 1918 France to 1932 California. That's a story that deals with racial inequality and racial injustice and murder and corruption and the opium trade. That's something that I've written and am very fond of and hope to explore in California, a different region of the country. And I've read some scripts that I didn't write that are remarkable, and which I'm considering strongly. But I really like telling stories about very flawed people who live in the margins, people who are dispossessed, people that seem to be under- and misrepresented in American cinema. I'm heavily influenced by European cinema, whether it be Claude Chabrol or the Dardenne brothers or Clare Denis. There are so many filmmakers that move me. Laurent Cantet's work is just extraordinary. These men and women are making some of the finest films of our time, and they influence me greatly. They write about the human condition, and that's what I want to explore.

OUT OF THE FURNACE is currently in theaters.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks