Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

This column will tackle an Oscar winner from each year starting with the inception of the Academy Awards in 1929. My goal is to highlight lesser-known films from throughout cinema history that were able pull down one (or more) of the Golden Statuettes that remain such an integral part of Hollywood lore. I will also take a close look at the actual element(s) that the film was given awards for, with my analysis on how they hold up with years (or decades) of cinematic history in the rearview since. This week, the topic is the 1930 winner of the "Best Writing" and "Best Sound Recording" Oscars, THE BIG HOUSE. Check back next Sunday for our next installment, which will deal with the 2011 winner for Best Foreign Language Film, IN A BETTER WORLD.

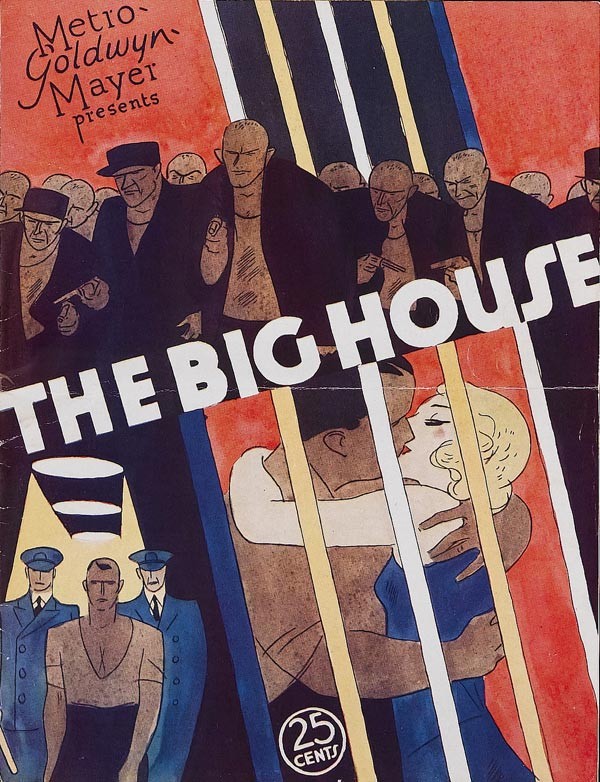

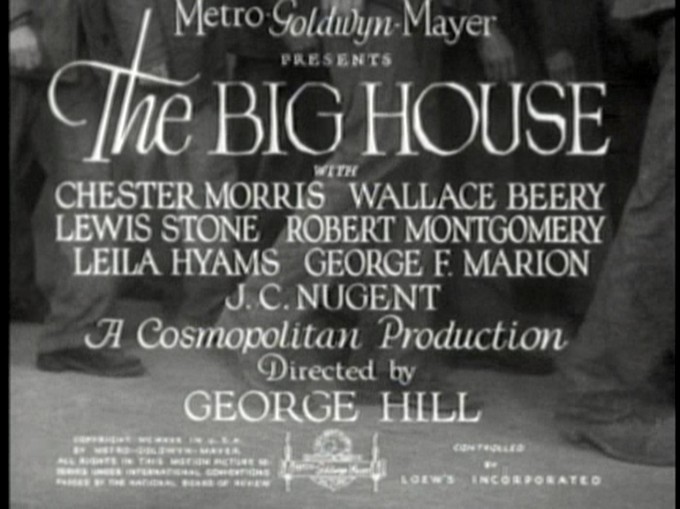

Before THE GREAT ESCAPE, before ESCAPE FROM ALCATRAZ, even before BIRDMAN OF ALCATRAZ, there was THE BIG HOUSE, which PrisonMovies.net calls "the daddy, the granddaddy, and even the great-grandaddy of all prison movies." George W. Hill's early talkie, about the ins and outs of prison life and what that environment does to the souls of men, pulled down two Oscars back in the 2nd Academy Awards ceremony of 1930, this one judging the films released from August 1st, 1929, through July 31st, 1930 (the Awards wouldn't settle into their now-familiar calendar year nomination system until the '35 ceremony).

Frances Marion (Hill's wife at the time) won the sole statue for what was then called "Best Writing," discrediting two other writers who worked on the picture (more on that later). The other golden boy went to Douglas Shearer, who won the first ever award for "Best Sound Recording" (which would be renamed "Best Sound" in 1959, and then finally "Best Sound Mixing" in 2004). Although it didn't take the Best Picture (then "Outstanding Picture") or Best Actor (for Wallace Beery) Oscars that it was up for, it won and was nominated for just as many awards (two and four, respectively) as the film that went home with them, ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (granted, there were only 8 categories that year, up one from the previous year's 7).

Given the awards bestowed upon it that fateful night in November of 1930, one could infer that THE BIG HOUSE featured a cracking utilization of the new medium of synced sound via its dialogue and sound effects. Does it? Funny you should ask...

The first thing we hear after the Metro Goldwyn-Mayer fanfare is the clomping of marching prisoners; this is the first of many instances we will hear this sound effect. After a glorious art-deco matte shot depicting a fortress-looking prison (complete with ominous, blackened smokestacks), we watch as two men in fedoras and dusters escort another dude in a fedora and duster (his black one distinguishing him from his brown-coated companions) into the processing chambers of said prison. A guard at the counter tells us who he is: "Kent Marlowe. Manslaughter. Sentenced to ten years."

Poor Kent (played by Robert Montgomery) has the look of a young man fully aware that a night of drunk driving has basically cost him his life; what he doesn't know is just how deeply prison life is about to change him. The guard lets him keep his smokes and photographs (including one of his dear sister), but then lets him know, "From now on, you're number 48642," as in, "You're ours now, boy."

After we've seen Kent get his mugshot taken, his fingerprints recorded, his measurements examined, his clothes issued, and even his introduction to the warden, you'd think this guy is the lead of the film. Well, he's not; our protagonist is one of Kent's two cellmates, streetwise forger John Morgan (Chester Morris). The third cellmate is a cueballed tough guy named Schmidt, commonly known as "The Machine-Gun Butch." Almost immediately, Kent is getting dominated by Butch, the guards, and his own sense of anxious disbelief.

Butch is a clear-cut menace and is confined to solitary after he starts hollering about the food during mealtime. Morgan, on the other hand, has done his time in an even-tempered, well-behaved manner, and is about to get out on parole. But Kent, in a panicky attempt at buying some good favor with the prison board, frames Morgan the day before he is supposed to get out, voiding his release and landing him in "the dungeon" in a cell alongside Butch. Luckily, Morgan's a quick thinker, and fakes his death in order to escape via the morgue transport.

On the outside, Morgan tracks down Kent's sister, Anne, with ambiguous intentions; is he there to get revenge on Kent for ratting him out, or did seeing her picture amongst Kent's possessions gave him the hots for her? Before we can find out, Anne passes up an opportunity to give Morgan up, and the two begin a tentative romance. By the time he gets picked up by a P.I. and shipped back off to the hooskow, Anne is crying into her mother's arms and declaring her love for him.

Morgan's back inside for all of 10 minutes before Butch comes up to him with a plan to break out. He convinces him that Kent wasn't the one who set him up, and that the scheme is foolproof, but Morgan insists he's gone legit and intends to do his time straight up. All of a sudden, Morgan, not Kent, is the one that Butch and his crew think is guilty of being a rat. That's when they get their hands on some firepower...

Like the last two vintage movies in this column, THE BROADWAY MELODY and UNDERWORLD, THE BIG HOUSE features a ton of elements that would become staples of its genre, in this case, the prison movie. The yard, the cell block, the mess hall, and even the warden's office all look like they would in countless prison films to follow. The prisoners are an eclectic bunch, alternating between a bunch of psycho looking dudes with angry faces, little shrimpy guys that look like Chesters that miss their Spikes, and most commonly, sad, lurching men who have clearly been broken by prison life. And you can bet your ass that the guards loom over those prisoners like death itself, anticipating them to make a wrong move the way a housewife looks at a teakettle before the water boils.

But it's the script, credited to Francis Marion (for "Story and Dialogue"), Joseph Farnham, and Martin Flavin (for "Additional Dialogue") that lays the most groundwork for prison films to come. Perhaps the story of the relatively innocent inmate who goes bad when surrounded by tough guys was a tired one even back in 1930, but probably never to the extremes here. When Kent, Butch, or even Morgan get backed up into a corner, things like morality, friendship, and hope go right out the window in a way that makes the flick feel more like anarchic 60s/70s films than a romanticized, studio-era prison flick. The goings on of prison life, which would become so central to establishing the tone in movies as varied as AMERICAN HISTORY X and GET THE GRINGO, are explored to such an extent that the New York Times review of the film describes the film as, "an insight into life in a jail that has never before been essayed on the screen." Bunch of other soon-to-be-cliches: the slang-riddled wise-guy dialogue, a character faking his death to sneak out of the joint, the jaded criminal contended to doing straight time, the lame-brained, almost childish behavior of the resident psychopath, and of course, the climactic riot/prison break.

Yes, the last 15 or so minutes is basically a massive action scene, where Butch's plan to escape ends up causing a full-scale riot, replete with loads of machine-gun fire, a whole buncha bodies, and fucking tanks (no one felt the need to call that shit in for Mickey and Mallory, I guess). It's the kind of big-scale set-piece, where all the unresolved plot points are quickly tied up amidst a loud, violent backdrop, that used to pop up at the end of pulpy dramas all the time (before the audience's dwindling attention span necessitated opening films with action beats). The right people die, the right people make it, and within a minute of screentime after watching his buddy bite it, the protagonist is in his love interest's arms. It's not like the dialogue is Mamet or anything, but I would've much rather preferred a more intimate ending, instead of the resolving-confusion-by-way-of-gunfire that is such a prominent element in both crime and prison movies. Maybe if the action was more clearly cut together, and not just a madcap assembly of geographically independent shots and moments, maybe it wouldn't bug me as much, but as is, it doesn't quite mesh with the more knowing, human stuff that comes before it.

Oddly, as much as the film contains tropes that would plague the prison genre in years to come, it also has a bunch of things about it that strike one as very odd and, in some cases, unfortunately dated. In future films, like THE LONGEST YARD, ANIMAL FACTORY, THE SHAWSHANK REDEMPTION, A PROPHET, we follow the "fresh meat" instead of the savvy "been-there-done-that" character. It's weird that they use Robert Montgomery's Kent to introduce you to the prison and its population, before having you turn on the character when he sets up the genial and understanding Morgan. It's weird that the film takes place fully within the confines of the prison, until about 50 minutes in, when Morgan goes on a several week sabbatical with a P.I. casually on his trail, evidently in no kind of rush to do his job and bring the guy in. And it's super-weird that our hero hunts down the sister of the guy who double-crossed him, only to fall madly in love with her (even weirder that she reciprocates).

There is an explanation for the weird, forced love story. Apparently, in the first cut of the film, Kent and Anne weren't siblings- they were a married couple. Test audiences (compromising interesting films since before most of us were born) ended up hating Chester Morris's Morgan for coveting a married woman more than they did Robert Montgomery's backstabbing Kent. Some reshoots and overdubs later, and Morgan just happens to fall for the single and beautiful Anne, who just happens to immediately take to this convicted felon who makes her his last stop before leaving the country (I swear to god, I think he was planning on icing her in her own shop, someone tell me if I'm off the mark on this).

Even if it would've made it hard to sympathize with the lead, I gotta say, I wish they kept the original setup. It would've added a little gray shading to the characters of Anne and Morgan, bringing them up to the complexity level of the brutish, but occasionally soft Butch and the vulnerable, selfish Kent. It would've made Kent's presence in the second half more than a walking series of plot contrivances, and it may have added an extra layer to the love story that would remove some of the forced arbitrariness from the couple's scenes together. Their connection would seem more like an instinctive stab against loneliness, rather than simply yielding to the machinations of the standard studio formula of "boy meets girl". But, alas, thanks solely to the cowardice of the studio (the Hays code, which wouldn't be instated for another 2 years, was certainly not to blame), the love story cripples the dramatic momentum of film's second half in a way that all the artillery and weaponized vehicles in the world couldn't solve.

Even though Martin Flavin and Joseph Farnham received an "Additional Dialogue by" credit alongside "Story and Dialogue by FRANCES MARION," only Marion took home an Oscar for her efforts. Interesting to note that the problems with WGA arbitration that plague Academy voters to this day are absolutely nothing new. I'd love to know which writers contributed what to the script, because all three were noteworthy scribes.

By the time she wrote THE BIG HOUSE, Marion had already penned 10 Mary Pickford movies, as well as pictures for Marion Davies, Lillian and Dorothy Gish, and Rudolph Valentino. She'd go on to win another Oscar two years later for her work on the Wallace Beery/Jackie Cooper classic, THE CHAMP, and received yet another nomination for the Myrna Loy/Max Baer (yes, that Max Baer) love story, THE PRIZEFIGHTER AND THE LADY.

Joseph Farnham, although he didn't win a statue for his contribution to THE BIG HOUSE, already had one under his belt; in the first Academy Awards, during a time when winners were awarded based on that year's entire body of work, his work on FAIR CO-ED, TELLING THE WORLD, and LAUGH, CLOWN, LAUGH won him the only award ever given for "Best Writing - Title Cards". His death of a heart attack (at the even-for-then young age of 46) less than 8 months after the '30 Academy Awards made him the first Oscar winner to pass away. THE BIG HOUSE contained his last credited work on a motion picture.

Of the three, perhaps Martin Flavin had the most distinguished career as a writer. He only contributed to three films following THE BIG HOUSE, but he wrote a bunch of plays both before and after his movie career, and one of his five novels, a 1943 examination of Americana entitled Journey in the Dark, actually won Flavin a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction (then called "Pulitzer Prize for The Novel").

Two Oscar-winners and a Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist. Wish more movies had that kind of writing pedigree these days.

Aside from the script, the other element of THE BIG HOUSE to take home an Oscar that night was its sound design by MGM's in-house sound guy, Douglas Shearer, who would go on to win 6 more statues, including two for Best Special Effects. The soundtrack features a lot of stuff we may take for granted in 2013, but if you imagine that diagetic sound had only been on the scene for a little more than 2 years, Shearer's efforts seem mighty impressive. There's a ton of background dialogue and ambient noise pouring out from every corner of the prison, making it feel less like a soundstage in Burbank than a hostile, cluttered jail.

There's a recurring aural motif of many prisoners marching in a row, and it plays a crucial part in setting up the film's subtext. At its heart, the film is a condemnation of the prison system, which feeds the impulses of its deranged and violent inmates, while turning good men into either sniveling cowards or helpless victims. Kent is shaking in his boots before he even enters the prison, and everything that happens to him (save for maybe Morgan's initial kindness) makes him increasingly more unsettled and pathetic, before going "yella" ultimately gets the better of him. The intimidatingly large Butch, who seems utterly devoted to his pal Morgan, is all-too-ready to pull a knife on his buddy or lay machine gun fire down on him when he thinks he's not on his side.

It's the marching which forces these personalities into a line, instinctively creating a tension within them that has no choice but to come out in ugly, destructive ways. Many of these guys wanted to get rich quick, or become higher-ups in their criminal syndicates but they fucked up, and now they're stuck with numbers on their chest, marching with the rest of the losers. What they're willing to do to steal back whatever sense of humanity they can muster after marching themselves into social insignificance is the driving force behind much of the narrative, up to and including the plight of the on-the-surface "cool guy", Morgan.

There are great cacophonies when the prisoners are amassed together, whether in prayer, at the cafeteria, or during the aforementioned marches. You know how sometimes in films of this era, when the shot cuts to a close-up, the background sound dies down? Not here. There's always something happening just offscreen, making it understandable when the prisoners mutter about their escape plans under their breath. You get the sense that there are a ton of loud, outspoken dudes in this prison, adding to the claustrophobic, powder keg tension of it all.

My favorite part of the film is something I haven't really talked about yet: Wallace Beery as Butch. Beery, who took the role when Lon Chaney was diagnosed with lung cancer prior to production, was nominated that year for Best Actor, but lost to George Arliss for his sound remake of 1921's DISRAELI; a shame, for I'd argue he is just as responsible (if not moreso) for the overall impact of the film. Beery's "Machine Gun Butch" is a wonderfully over-the-top character who gets nearly all of the film's best lines and moments. In his first scene, he is hesitant to welcome Kent to share his cell, until he hears that he's locked up for manslaughter. He beams, "Well, you ain't no morning glory after all!" before vigorously shaking his hand, curiously inquiring, "Who'd you croak?" He mentions an old girlfriend: "Sadie was a good skirt. I shouldn't have slipped her that ant poison. I should've just batted her in the jaw a few times." There's a classic bit in the cafeteria, spoofed in NAKED GUN 33 1/3, where Butch loudly complains about the "swill" being served to him and other prisoners, inciting an impromptu uproar that lands him in "the dungeon" (solitary confinement). Beery had the kind of physique that could've gotten him by playing thuggy brutes like the ones Mike Mazurki made a career out of, but it's his comic timing and bizarre sentimentality that makes his character the most interesting in the picture.

One great early scene has Butch getting a letter from the outside. He reads it to his excited gang; a girl named Myrtle tells Butch how she dreams about him and can't wait to get out. Butch cuts himself off towards the end, saying it's "too juicy" for anyone besides himself and his cellmate, Morgan. Once they're alone, Butch admits that he can't read, and has no idea what the letter actually says. Morgan grimly tells Butch that his mother had grown sick and died. Butch mourns his mother, before snickering at his own ruse. "If I even knew a girl named Myrtle, I'd kick her teeth in." Beery goes from the grinning braggart to the insecure fool to the grieving son to the comically comfortable-with-it psychopath in the span of one scene. It's really dynamite stuff, leagues better than his climactic scenes when he devolves into the raging villain that the violent climax necessitates.

Beery had been a major player in the '20s (appearing, among many others, in THE FOUR HORSEMEN OF THE APOCALYPSE, ROBIN HOOD with Douglas Fairbanks, and 1925's THE LOST WORLD), but by the talkie era, he was all but forgotten. After his performance in the film brought him back into the limelight, he played in the big hit MIN AND BILL (also written by Frances Marion), won his Oscar for THE CHAMP, and appeared in the '32 Best Picture winner GRAND HOTEL. He'd go on to work regularly in the industry for 20 years until his death in 1949.

The other performances in the movie are okay, but nothing super-memorable. Chester Morris has moments as the lead, Morgan, but he's way too cool and unaffected to be a truly interesting protagonist. Robert Montgomery is strong as he devolves into confused alienation in the first half, but his Kent has nowhere to go from there, and is relegated to being the kind of lame, pathetic snake that the scuzziest Peter Lorre character would step over carefully lest he dirty his shoes. Lewis Stone's Warden has the unfortunate burden of being less of a character than a necessity of the trappings. He knows far, far too much about the inner nature of every convict he encounters, and basically lays out the thematic substance of the film in each of his long-winded speeches. There are some colorful performances by the other inmates, and some slick, effective work done by Robert Emmett O'Connor as the private dick, Donlin, but this is Beery's movie, through and through.

While the Academy awarded the film nominations for its sound, acting, and writing, director George W. Hill and cinematographer Harold Wenstrom (who would also work on MIN AND BILL that year) went unrecognized. Too bad, 'cause I feel that their work on the film is also a big factor in its lasting influence and appeal. The arch shadows, the cramped staging, the unbroken long shots, the balance of absurdity and drama, these are all memorable elements of the film, just as much as the pulpy dialogue and the affecting sound design. I guess Hill had an uphill battle, going up against the likes of King Vidor (for HALLELUJAH!), Ernst Lubitsch (for THE LOVE PARADE), Clarence Brown (for ANNA CHRISTIE and ROMANCE), and THE GREAT ZIEGFIELD director Robert Z. Leonard (for THE DIVORCEE). I'm less certain why they couldn't throw Wenstrom a nom for basically creating the visual template of the 20th-century prison film, but hey, 20/20 hindsight's a bitch.

Interestingly enough, Leonard's THE DIVORCEE (which was also nominated for Best Picture and Best Actress for Norma Shearer, who won) also featured THE BIG HOUSE stars Chester Morris and Robert Montgomery. There, Montgomery messes with Morris' life yet again by sleeping with his character's wife, driving him to alcoholism; I'm curious to see the flick if only to see the contrast between the two actors' performances in the two films.

THE BIG HOUSE and THE DIVORCEE earned wunderkind MGM producer Irving Thalberg another two Outstanding Picture nominations, after the previous year's two for HOLLYWOOD REVUE and THE BROADWAY MELODY; unfortunately, unlike that year, he didn't end up going home with the award. Even though he tragically died less than 6 years later (of pneumonia, at the young age of 36), his films would go on to earn another 8 Best Picture nominations, including two wins for GRAND HOTEL (1932) and the Charles Laughton/Clark Gable MUTINY ON THE BOUNTY (1935)

Is this film as worthy of recognition as some of Thalberg's other pictures? Probably not; the drama of the film is too simple and pulpy to have any sort of real emotional impact, and the humor is perhaps a little too prevalently goofy to really do the prison setting justice. The sound design and the script earned THE BIG HOUSE it's place in the pantheon of Oscar winners. However, in my 2013 mind, the awards given to it distinguish the flick more for its impact on cinema (both prison-set films and otherwise) in years to come than the remaining potency of those elements in context. Watching the movie today, it's astounding that the one quality of the film I would deem truly Award-worthy, namely Wallace Beery's performance, failed to get the hulky-looking actor his Oscar; luckily, because it was able to lock down two awards that night, Beery's performance (and the other impressive aspects of the production) will be appreciated by cinephiles curious to know what this prison movie prototype was all about. And that's a good thing.

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter