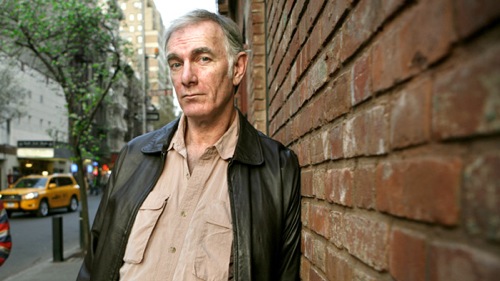

The American film revolution of the 1970s was drawing to a close when writer-director John Sayles's RETURN OF THE SECAUCUS 7 ambled its way into theaters. At a time when Hollywood studios were beginning to fill their ranks with brash young executives who believed they'd figured out the blockbuster formula, the modest success of this very modestly-financed motion picture couldn't have been more crucial. It's a small film about a group of college friends who reunite for a weekend of melancholy reminiscence in New Hampshire, and what it lacks in dramatic stakes it more than makes up for in finely observed human behavior. Made for $60,000, it went on to gross $2 million, proving to young filmmakers that there was a career somewhere outside of the mainstream movie industry.

But that $60,000 wasn't raised on the strength of a wonderfully nuanced screenplay. It was earned in the filmmaking trenches of Roger Corman's New World Pictures empire, where Sayles toiled with the likes of Jonathan Demme, Joe Dante and Allan Arkush on all manner of exploitation movies. So while RETURN OF THE SECAUCUS 7 was quietly finding an audience, the Sayles-scripted quartet of PIRANHA, THE LADY IN RED, ALLIGATOR and BATTLE BEYOND THE STARS were all flickering away in theaters nationwide (along with countless other Corman quickies). I have a great deal of affection for those movies, but had Sayles segued into studio filmmaking like most of his Corman cohorts, we would've never got EIGHT MEN OUT, MATEWAN, THE BROTHER FROM ANOTHER PLANET, CITY OF HOPE, THE SECRET OF ROAN INISH, PASSION FISH, LIMBO or, god forbid, LONE STAR. What a loss that would've been.

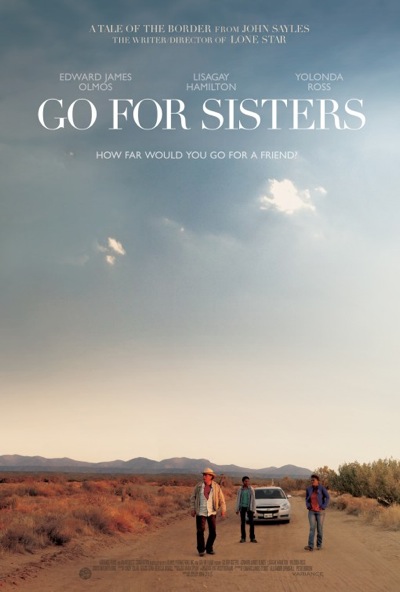

Over the last thirty-three years, Sayles has maintained a healthy creative balance: he takes for-hire studio screenwriting gigs (for which he rarely receives credit), while rounding up as much financing as possible for his personal projects. His latest film, GO FOR SISTERS, was made for well under a million dollars, which is what happens when you write a low-key character study of two middle-aged African-American women that casually turns into an equally low-key detective yarn. There's no dynamic trailer to be cut from this film; it's a smart, wittily patient examination of two former friends sliding back into each other's lives. Bernice (LisaGay Hamilton) is a parole officer desperate to find her missing son; Fontayne (Yolonda Ross) is a recovering drug addict who's trying to stay clean and out of the joint. Later, they seek the assistance of a disgraced ex-cop, Freddy Suárez (Edward James Olmos), whose vision is rapidly degenerating. Though Sayles makes use of several genre conventions to keep the story moving (the Olmos arc recalls Art Carney in THE LATE SHOW), he keeps the emphasis fixed on character: we're not waiting for some nefarious drug lord to get gunned down; we just want these decent, struggling people to find a measure of redemption and peace.

This is Sayles's first feature in three years, and, in my estimation, his finest work since the vastly under-appreciated LIMBO. When I sat down to chat with the filmmaker at the movie's Los Angeles press day a week ago, I had around four pages of questions. Over the course of a half-hour, I got through most of one page. As expected, Sayles was an eloquent interview - full of amusing anecdotes and fascinating insights into the life of a professional screenwriter. At the end of our conversation, he dropped a tidbit about a TV series he's developing with Joe Dante, Allan Arkush and Elizabeth Stanley. If they pull it off, it could very well be my favorite show of all time.

Mr. Beaks: It's a real pleasure to fall into a movie where we gradually discover the story through the characters. Do you find it's a rarity for people to write this way now?

John Sayles: You just have to realize that the economics of film are such that most films have to be very, very conscious of playing to the largest audience possible, and, therefore, things can get a little formulaic because it's a big economic adventure for everybody. "Let's not take any chances." Even if it's about something new, they'll say, "People like fast cutting, and we're going to lose the audience if we do this." Because I'm not playing in that economic arena, I get to do different things. This is a movie that starts with a page-and-a-half monologue from a character that you never see again. Tessa Rose Ferrer is terrific, but people are saying, "So is the movie about her?" And then you realize, "No, it's about the parole officer." And then the other co-star shows up, and a half-hour later Edward James Olmos shows up, and it becomes even a different story. That's the kind of thing that as a screenwriter-for-hire I would never do, when my job is to make a much more commercial, mainstream movie that's going to cost a lot more money to make.

Beaks: Where do you start typically as a writer? Are you thinking about a character or is it a premise?

Sayles: Usually it's characters in a situation. Who's the character that I want to look into, and what's a situation that will bring certain things out, that will be dramatic? A lot of times, what a dramatic situation will be... in a clear heroic movie, it'll be "There's the bad guys, and I have to kill them without getting killed." That's a fairly easy situation. But when you get in a situation where maybe these people are bad guys, but there's no way for me to fight them without risking not my life, but somebody else's life... is that worth it?" That's more interesting. So with GO FOR SISTERS, I had two different ideas that I walked around with for ten or twelve years, one being about two women who had known each other, were separated for a long time, and then reunited when life had happened to them and they were in very different places, including that their status had changed. They came from almost the same status, and it can happen that somebody has gotten famous, somebody has gotten rich, somebody has gotten married, and can you still be friends anymore? And can you still find that person you liked, who helped you like yourself, or is that person just gone? In one of the cases in this movie, when Fontayne meets Chula, who she had this really heavy affair with in the joint, she's still saying, "Is there any opening here?" But Chula has put a firewall between her life now and her life then. The answer there is no. The answer between Fontayne and Bernice is that it's going to take a while, but they're bringing out something good that they like about themselves in each other.

That was one of the ideas. The other idea was a totally separate idea about a detective who is kicked off the force basically not for doing anything really bad, but for kind of living up to the code of these guys who work together, which is "I'm not going to rat you out. I might say to you privately that you're in over your head, that you're doing something wrong, but I'm not going to go to the force and say 'Hey, this guy is taking money.'" So he looks away, and there's a sting. He gets in trouble and loses his pension, even though he doesn't go to jail or anything like that. But he's disgraced. Is there a second act after that? That's what you've done your whole life, and that's what you've felt good about. It could've been "What happened to the guys in EIGHT MEN OUT after they got kicked out of baseball?" You know it was harder for them for the first five or ten years when they could still be playing than it was when they got older and would've been out of the game anyway. So when I seriously started thinking about making this movie, I realized I could combine these two ideas, and I could go from basically a two-hander into a triangle, which is more interesting, and they could both have trajectories. They all have agendas that are very different than each other, but they have to do this thing together.

Beaks: You said you had these stories kicking around for ten or twelve years. Just how many ideas do you have kicking around like that?

Sayles: I have a lot, and with some of them never enough sticks to them. Some of them get made into short stories or novels, and some of them get made into screenplays that I'll probably never get to make because they're much more expensive than this. This was the thing: with the money I had in my pocket at the time, I felt like, "Yeah, I could probably make [GO FOR SISTERS]." And quite honestly, I had a little less than what I think I should've had to make this. I didn't pay people as well as I would've liked to, and had only nineteen days to shoot. It would've been nice to have twenty, maybe twenty-five days, just for the experience and the "This is your life" part of it - not that the movie would be that much better or anything if we had a little more time and a little more money. But I have other ideas that there's no way I could make them for under a million dollars, or what I'll ever be able to make in my whole life as a screenwriter.

Beaks: How far will you allow yourself to go into a screenplay before you shove it aside?

Sayles: Up until the last couple of years, I'll usually write it out just because it's fun to write on your own. Nobody's breathing over your back, and you don't have to worry about it. And then very often I read it, and I may not do another draft because I just realize there's no way in hell I'll ever be able to raise the money to do that. But I've got two or three that I'd love to get financed that I'm not ever going to make unless someone taps me on the shoulder and says "Here's the money." I think all filmmakers have a couple of those. There's famous movies that never got made. Eisenstein went to Hollywood and he was going to make AN AMERICAN TRAGEDY, and that never happened. Orson Welles was going to make DON QUIXOTE and HEART OF DARKNESS, and those never got made. In some cases, the screenplays are there, the storyboards are there, and all that other stuff. I've got quite a few of those.

Beaks: When it comes to taking pleasure in writing, how different is writing for yourself from writing for-hire? Is there still pleasure in the latter?

Sayles: The first draft is always fun because that's the one where you feel like, "Well, if I was going to get to make this movie, this is what I would do." Then the notes come in, and they have different agendas. Sometimes they're good notes, and sometimes you don't know where they're coming from - or they're confusing because they're coming from different places, and people want different things. That's when it gets political and practical, and those are more work than fun generally. But the first draft is always fun - for me, anyway, or else I wouldn't have taken the job. But most of those don't get made. Most movies that screenwriters who get paid to write don't get made. And most movies that screenwriters who don't get paid to write don't get made either. It's "Many are called, but few are chosen."

But you're really an employee when you're working for someone else. You're helping them tell their story. In one sentence [while making THE CHALLENGE], John Frankenheimer said "Yeah, I know it's all set in China with Chinese martial arts, but I can get Toshiro Mifune in this movie, so let's make it all Japanese." I said, "You know, these martial arts cultures are very different." And he said, "I can get Toshiro Mifune." So, boom, I changed everything. I had a couple of days to do it, and it made it a very different movie in some ways, but that was where they wanted to take the story. That was my job. When I write something for myself, I'm either going to get to make it or I'm not, but I'm not going to change something just because somebody decides it should star a certain actor or be shot in this location or, "We'll get more people to come if the woman is twenty instead of forty."

Beaks: I really like THE CHALLENGE by the way.

Sayles: It was interesting. When Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel had their show that they used to give the "Dog of the Week" on, they said, "Okay, we thought [THE CHALLENGE] was going to be our 'Dog of the Week' because it was a studio movie that didn't have a press preview. Then we watched the movie and liked it!" So good for them, because it's easier to say bad things about a movie as a critic than good things, and they just said, "Nope, this is a good movie!"

Beaks: Ballpark: how many for-hire gigs do you think you've taken over the years?

Sayles: I think I finally hit 100 screenplays that I've written, whether they were TV movies or features. I think I've written all eighteen different features I did make, and there's probably another five or six that I haven't made. So it's probably about seventy to seventy-five movies for other people in some stage or another, like pilots for TV shows that never got made. And some of then have gotten made. My batting average is probably pretty good because I started out working for Roger Corman, and if he paid you $10,000 to write a movie, he was going to make it. He wasn't going to leave that money on the table.

Beaks: When you're writing and directing a movie for yourself, are you still taking other assignments?

Sayles: Economically, I'm almost always having to, especially if I'm financing or if I'm one of the financiers of the movie. I'm writing during prep, and I'm often writing while I'm editing, so I'll keep a couple of hours a day for writing, then do the fun stuff, which is editing or whatever. We were in Ireland prepping for THE SECRET OF ROAN INISH, and I don't like to have an office with a door that separates me, so I was at a table just like this one right next to the woman who was the production office coordinator, who was doing all the planning. I'd been working on this script for a week, and I finally said, "Could you do me a favor? Could you print this and send it out to L.A.?" She said, "This isn't this movie?" She thought I was rewriting [ROAN INISH], and she was panicked that she was going to get all of these new pages. I think I handed in that [for-hire screenplay] three days before shooting. So, yeah, I often am having to do both things, which is not necessarily bad. They're both completely different. It's just that you've got to put the time in.

Beaks: How do you keep those commercial instincts from bleeding into your more personal work?

Sayles: I don't have any problem with our movies being commercial. Truly, I've made a couple of movies that I thought were very commercial, but we just didn't have the money. I think if a studio had put HONEYDRIPPER out, and put the kind of money they'd put into a Tyler Perry movie, it would've been a box-office success. Maybe not a huge hit, but it would've made money for a studio if they'd been able to advertise it. We've had two or three movies like that.

But it's basically here is the story you want to tell, and then you have to be realistic about how much you can spend on it - especially if you're going to other people asking for their money. We're always very aware when we're looking for money to ask "What does this person want out of this? Do they want to make a profit?" We're going to be honest with them and say, "You could invest in a studio movie, and you're not going to make a profit. Go to the track if you want to make a profit. Bet on the horse with the jockey wearing green every race and you'll probably do better than investing in movies." But if you've got money to play with, and you want to play in the movies, maybe you want to get your feet wet with one of our little movies and see what the process is like. We've had a couple of investors like that, who've put half-a-million dollars into a small movie, and really got to learn what the process was and whether they liked it or not. They'll either stay in it and go on to bigger movies, or not. Sometimes it's, "Oh, I want a movie shot in my home state," or "I want to meet Cameron Diaz." And that can be, "We can arrange that." But you really want people to get what they want out of the movie. And sometimes you have to say, "No, we're not going to take your money because you're not going to be happy. You're going to make our lives hell."

Beaks: I've always wanted to ask you about LIMBO, which was one of the most memorable moviegoing experiences of my life. Did you ever experience that movie with an audience, and what did you think of the reaction?

Sayles: On the East Coast, there are a bunch of guys who have these film series in a mall or something like that, and every week they show a new movie that people don't know. I remember walking into the end of that, and a guy walking out shouting, "You fucking prick!" He wasn't even saying it to me; he was saying it to the movie. I'd say with LIMBO, a third of the audience got the ending right away, about a third got it the next day, and a third still don't like it. I heard from a couple of people back when there were Blockbusters and video rental stores; they said people would bring the movie back and say, "The last reel is missing. There's a jump, and then it goes right to the credits." And they'd say, "No, I think that's the movie."

First of all, let's just say, "What's the title?" That's a consumer warning. "You will be left in limbo." The ending was the first thing I knew about that movie. So many movies are about "Does the hero get shot or not?" That's all they're really about. For me, it's a movie about risk. People stay in limbo because they're afraid to take risks. It may be a bad marriage, it may be a terrible job, it may be a terrible political situation. Maybe you should have a revolution, but if you have a revolution you may fail and you may get hanged. So they say, "Eh, I'll keep treading water in this terrible situation." At the end of that movie, they don't stay in the woods. They come out on the beach. I didn't want to say - which is a very Hollywood thing now - that "All you've got to do is take a risk, and you'll be successful!" That's not true. You may get squashed if you take a risk. But you've got to take a risk or you'll never have a chance at succeeding. For me, the movie had to end with them taking the risk, and not knowing whether it was foreordained or whatever - which is taking it out of the movie world. There are movie rules that movie-movies follow, and people feel comfortable with those. I think the third of the people who didn't like it thought they were at a movie-movie. "I've made a deal, I've walked into a movie, and they're going to give me a satisfying, uplifting experience, and I don't know how this fucking thing ended!" To me, it's ended when they walk out on the beach, and anything else is something I can't tell you.

Beaks: I went to a screening in New York City, and was discussing the ending with my friend as we walked out. We both liked it, which, sort of like your experience, prompted this guy to confront us and say, "It was bullshit! Why couldn't Kris Kristofferson have been on the plane with the bad guys? He could've pulled a rifle and saved them!" I was like, "Is that really the movie you wanted to see?"

Sayles: He should work as a studio executive or a story consultant. You know, LIMBO was in the competition at Cannes, and somebody told me, "There were a lot of people booing it." I said, "Oh, those are the Americans. Europeans whistle." (Laughs) There were some Americans who liked it and some who didn't.

Beaks: In terms of writing to theme, where theme is going to be just as important as the story you're telling, how do you moderate that so that the theme doesn't become overstated or heavy-handed?

Sayles: The theme usually comes in in the second or third draft, and I only do three drafts. It evolves from what I'm writing about. As I said, I start with characters in an interesting dramatic situation, and then as I read it over the first time, I feel like very often the glue that holds it together is going to be the thematic glue and the arc of the characters. Very often I say, "There's kind of a story here, and there's a bunch of great scenes, but what's the glue that holds it together?" Then I say, "What's this movie saying about the world?" Or "What's this movie saying about this situation?" Then I may go in and add some things that are really just there for theme and coherency of the story arc. You don't start with theme and try to invent something that illustrates this point that you're trying to make. You realize, "What are the things that it's talking about, and is that really what I feel about this? What does this indicate?" For instance, people were talking this morning about having a lot of African-American characters and women characters. One of the things I always felt watching older movies, when those characters first started showing up in movies, is "There's a lot of weight on Sidney Poitier. He's the only guy there. He's representing the entire race." That's a statement. "You should get this magic negro, and it'll be perfect." But that doesn't have a lot to do with life, where the color of a person's skin really doesn't tell you anything about them. There's such a range of behavior in people. One of the things I was always careful about was, "I'm not going to have one black character. They come from a world. They're in that world. I'm not going to have one Hispanic. There's going to be a range of behavior here, and it's not going to be based on their race. It's going to be based on who they are." So to a certain extent, it's not so much theme sometimes, but a way of seeing the world. And when you see the most violent reactions to movies, it's usually not that they just didn't like the movie; it's that you upset their view of the world. That's really interesting to me. "Why does that get under somebody's skin? What did they really not like about that?"

And then I think a lot people like to go to the movies and just turn that off. "Maybe that's kind of fascist, but it's just a movie." Whereas for me, if it's kind of fascist, it's kind of fascist. A good example is GONE WITH THE WIND. I didn't see GONE WITH THE WIND until I was in my forties, and I just thought, "My god, what an incredibly racist, apology-for-slavery piece of bullshit this is." I understand the soap opera stuff of why it's popular, but what is this movie saying? How do you get away with that, and could you get away with it today? Maybe if I'd seen it when it came out, and I was a young person, maybe it would've been romantic and all that stuff. But I think a lot of people go in and say, "It's GONE WITH THE WIND. It's got beautiful music and beautiful costumes and it's a moving story about this woman." The other stuff? They don't even see it. I think people are sensitive to different things. I know people who are musicians who can't stand movies because they don't like the music. Sometimes, it's just really well done movie music that is almost invisible, but something grates about the music to them.

Beaks: You ever get any Texans who take issue with LONE STAR?

Sayles: Texans love movies about themselves, so that was a lot of the reaction we got from that. It's the same thing with West Virginians and MATEWAN. It's tough history, but almost every Q&A I do, I'll see some guy come up and I'll say, "This guy's either from West Virginia or Kentucky, and he's going to say, 'Well, my daddy was in the mines..." which is nice! The same thing with PASSION FISH and Louisiana. Cajun people had never seen themselves where they weren't inbred and killing people in the swamps.

Beaks: You're talking about all of these different regions. How do you get an ear for these different types of people?

Sayles: In my either physical travels or research travels, you'll run across a place that has a personality, and that becomes a character in the film. How does that change the film? If you look at that [points to the GO FOR SISTERS poster], that's a Southwestern film. You can't get that look in Rhode Island. West Virginia, you're in a holler and even though you're outdoors, there's something claustrophobic about it. Just the physicality about a place gives you some part of the story, but sometimes also the culture does. For instance, I think race is an absolute illusion. If you know anything about genetics, it's an illusion. But culture is really deep: you can be the same race, but from different cultures and really not have a whole lot in common. So I'm really interested in how regional culture... it's not just the food, it's not just the music, although those are parts that give you the flavor of a place... it's how do people think there.

That includes period. When I write a period movie, you ask these basic questions. "Is this before or after Freud?" The way human beings think was really affected by Freud; it eventually got into the general populace about people understanding each other and looking into motivations and not just noble birth. "Is this before or after capitalism?" "Is it before or after the women's movement?" "Is it before or after 9/11?" Those things really change things quite a bit - not just the clothing, but "What could this person know? What would he think? How would he see the world?"

Beaks: One of your most notorious unmade for-hire screenplays is JURASSIC PARK IV. It's been written about online many times, and has this hook that I think is terrific: dinosaurs on a mission.

Sayles: I keep hearing that they've made it. If they've made it, they've had a lot of time to move quite far from what I did with it, but I'll be eager to see it and see that they did with it. I did a draft of THE MUMMY when Joe Dante was going to direct it. Eventually, when the movie came out, because I'm in the Writers Guild, they do an adjudication. "Here's the final script. Do you want to claim any credit?" There were fifteen different writers on THE MUMMY over quite a long period, including George Romero twice. I read it and I said, "Well, there's sand and a guy wrapped in bandages and he speaks Farsi at some point, but other than that, I'm not going to take any credit." I thought they made a very good movie, but they went in a totally different direction. So I imagine if and when JURASSIC PARK IV finally comes out, what I know is it'll be something very, very different, because they don't need to just drag people back to the island again and have big dinosaurs eat them. That's what they were looking into doing, and I'll be fascinated to see what they do with it.

Beaks: You mention almost doing THE MUMMY with Joe Dante. Is there any chance of you two getting together for another project?

Sayles: We've been talking. Joe and Elizabeth Stanley and Allan Arkush and I have been talking about trying to pitch a TV series that's about a bunch of young people working for a Roger Corman type of producer in the early 1970s - which was a great time. Plus, I think you've got all those genre movies to hit on, and a bunch of young people making no money but getting to make feature films in the '70s. Sex, drugs, rock-and-roll, and making movies that are about sex, drugs and rock-and-roll? I think it would be a great series.

Yes, please!

For now, you absolutely need to get out and see GO FOR SISTERS, which is currently playing in New York and Los Angeles. To see if/when it might open at a theater near you, check the film's official website.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks