Papa Vinyard here, now here's a little somethin' for ya...

This column will tackle an Oscar winner from each year starting with the inception of the Academy Awards in 1929. My goal is to highlight lesser-known films from throughout cinema history that were able pull down one (or more) of the Golden Statuettes that remain such an integral part of Hollywood lore. I will also take a close look at the actual element(s) that the film was given awards for, with my analysis on how they hold up with years (or decades) of cinematic history in the rearview since. This week, the topic is the 1929 Best Picture (then called "Outstanding Picture") winner, THE BROADWAY MELODY. Come back next Sunday, when I'll be doing a Streep-tease over THE IRON LADY.

Anyone who's seen SINGIN' IN THE RAIN or THE ARTIST, or is simply well-versed in Hollywood history, is aware that the transition from silent film to talkies caused a sudden, jarring shift within the industry. While those films focus on the onscreen talents' struggle to maintain relevance while the zeitgeist changed around them, the technical adjustment to shooting with synced sound was maybe just as monumental and difficult.

THE JAZZ SINGER, the first "sound picture", was as groundbreaking and influential as anything else in cinema history (technically, at least), yet only scored a lone "Special" Oscar, given to Warner Bros., "For producing THE JAZZ SINGER, the pioneer outstanding talking picture, which has revolutionized the industry" (it also received a nomination for "Best Writing, Adapted Story"). Amongst the other nominees, only GLORIOUS BETSY, a love story about Napoleon's brother Jerome (not kidding), featured sound sequences (that have been lost to the annals of time).

However, the following Academy Awards had four sound films in the running for Best Picture; the Ernst Lubitch film THE PATRIOT was the lone silent picture nominated for the Academy's top award that year (and, to my knowledge, the last until THE ARTIST). None of the Oscars that year were awarded to films without at least some sound sequences.

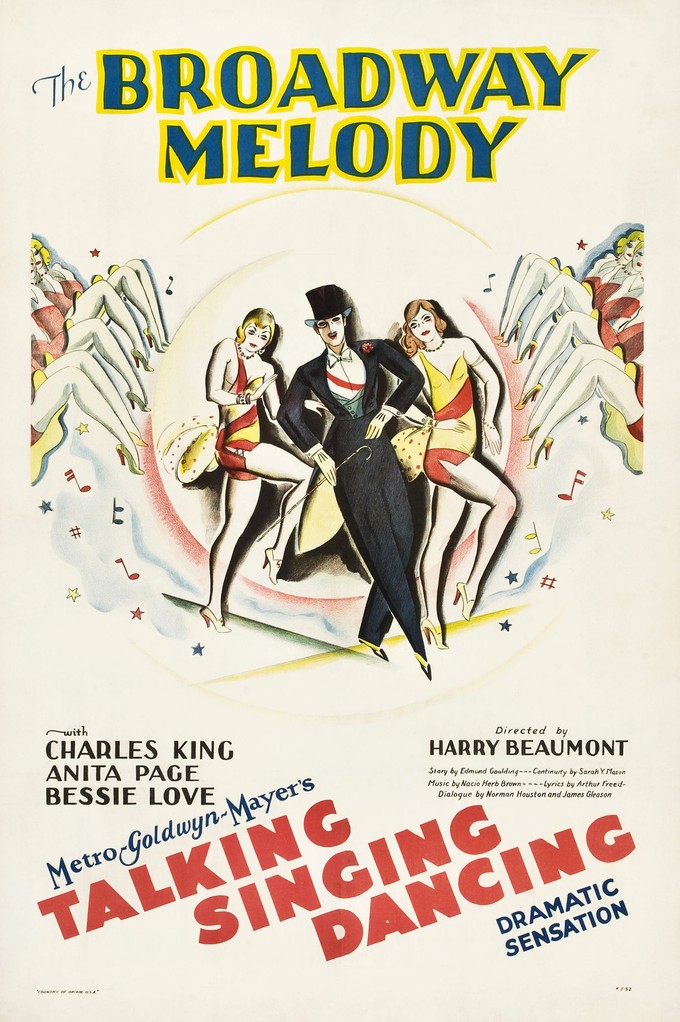

The winner of the second Academy Award for "Outstanding Picture" was the Irving Thalberg-produced, Harry Beaumont-directed THE BROADWAY MELODY. Aside from its win, Beaumont (THE GOLD DIGGERS, DANCE, FOOLS, DANCE) was nominated for Best Director, while Bessie Love pulled down a nom for Best Actress. To date, the (1st) 1930 Academy Awards (which judged films released from August 1, 1928 to July 31, 1929) is the only ceremony that did not honor any film with more than one award (there were seven total categories that year). This fact, alongside the knowledge that the industry was in the process of transitioning from silent film to sound, has given THE BROADWAY MELODY somewhat of a reputation for being a terrible Best Picture winner.

Is that fair? Well…

After some aerial shots of 1920's New York (which, aside from an astoundingly low-key Financial District and an annoying lack of car traffic, looks an awful lot like it does today) set to "Give My Regards To Broadway", we arrive at the offices of the "Gleason Music Publishing Co.", where Eddie Kearns (played by Charles King) shows off a new piece of music he's written, entitled "The Broadway Melody." A couple of actresses try to snag the piece for themselves, telling Kearns they'll "smack it over," but he insists that its being saved for the Mahoney Sisters, half of whom he claims "is gonna be the future Mrs. Eddie Kearns".

The Mahoney Sisters are Queenie (Anita Page) and Harriet a.k.a. Hank (Bessie Love), and they've just come to New York from "out west" to try and make it onstage with their act. Hank, the elder sister, is "the ability", the sharper and funnier of the two while Queenie, "the looks", is a more impressionable, open-faced blonde. They're fully aware of their dynamic; Hank even tells Queenie, "Baby, they were plenty smart when they made you beautiful."

Eddie visits their hotel room, and while its apparent that Hank was the one he referenced as being his fiancee, he is instantly and obviously smitten with the younger, more beautiful Queenie. Eddie promises the duo that they can perform "The Broadway Melody" for producer Francis Zanfield's musical revue, and takes them to audition for him. He's less than amazed: "I can use the blonde, but that little cluck is out."

Luckily, Queenie is able to parlay her good fortune to include Hank in the act, but when the two rehearse the act, Zanfield deems it too sluggish and axes the two from the show. Queenie, however, is able to snag the spot of an injured background dancer and becomes a hit with the audience, particularly a cad named Jacques Warriner. She's not crazy about the fellow, but when Eddie makes a blatant pass at her in front of her sister, she relents and goes out with him.

Sooner than later, Queenie starts to get impressed by Jacques' wealth, and strongly considers shacking up with the rich bachelor instead of hacking it out as a struggling performer, but it's all deflection to ensure that Eddie, who she's developed feelings for, will end up with Hank. While Hank and Eddie protest Queenie's relationship, she insists on letting herself be bought by her new beau and from there, it's only a matter of time before the relationships between all three are tested and warped to a compromised, but acceptable conclusion.

While it came out over a year and a half after THE JAZZ SINGER, THE BROADWAY MELODY features a shit-ton of tropes from the silent film era. There are interstitials in between the scenes to let the audience know where they are, in the place of exterior shots or inserts. It's very bizarre to be watching a talkie when a scene ends and fades to black, and the words "Zanfield's Theatre, during the rehearsal of the last revue." come on the screen. It'd be like a contemporary family film having a kid break out an old-school, brick-shaped Game Boy; sure, it doesn't ruin the movie or anything, but you'd really think the filmmakers would get with the times already for the sake of the audience.

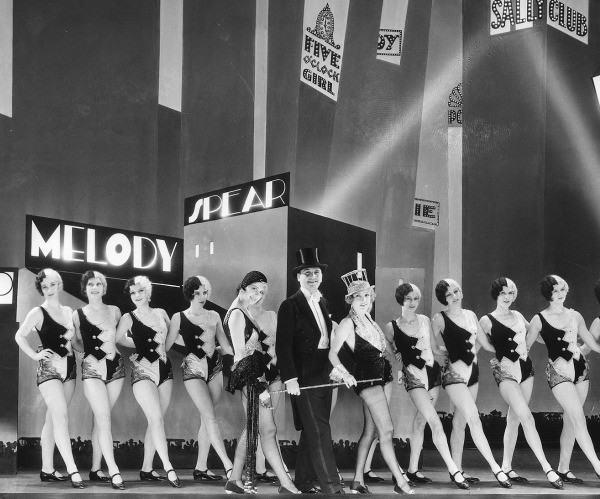

While there are no blatantly obvious giveaways that its an early sound film (like actors leaning in to make sure a stationary microphone picks up their dialogue), the film is generally staged like a holdover from the silent picture era, mostly alternating between wide shots featuring the whole set and awkward, overlong close-ups to highlight the actors' expressions. The musical scenes are mostly set onstage or in rehearsal scenes (save for Eddie's use of "You Were Meant For Me" to serenade Queenie), and the settings never expand into surreal extravagance the way they would in a Busby Berkley film. There is an odd rhythm to the editing, with several comic beats coming off as rushed and bizarre, while the dramatic moments are often too drawn out, noticeably forced, and artificial.

Bessie Love, as Hank, is the "third wheel" of the central love triangle but with her lively acting, her aggressive personality, and her quick wit, she steals the show from her two co-leads. It is clear that Ms. Love had honed her craft before the advent of sound, with her loud facial expressions and stagey, borderline over-the-top acting. However, this ends up working toward her advantage, both by adding a little pathos to her desperate-for-approval character, and also because her demeanor ends up serving as the heart of the picture.

There's a terrific, late scene of Hank breaking down in tears that comes off as far more raw and painful than many sound-era actresses would've played it, with her gasping and trembling coming off more like those of a hysterical, heartbroken woman than a young actress vying for the spotlight. It's so unexpectedly affecting that it's an absolute no-brainer that she pulled down the lone acting nom for this film. In his otherwise lukewarm review for the New York Times, Mordaunt Hall notes that Love "is capital in either her tempestuous or tearful periods. She reveals imagination in dealing with her part, notably during one stretch when she is weeping as she lathers her face with cold cream." While she initially had some trouble maintaining relevance in the sound-film era, Love worked consistently from the early-'50s onward, popping up in movies like ON HER MAJESTY'S SECRET SERVICE, REDS, and RAGTIME before retiring at 85.

Charles King and Anita Page are solid, if unmemorable, as the other two stars of the picture, with King's singing being the highlight of his performance, and Page's insecure beauty almost justifying her solo screentime away from Ms. Love. Page and Love have better-than-average chemistry, reminding me of Romy and Michele (of HIGH SCHOOL REUNION fame) in more than one instance. Like Love, King also shows a little lingering silent-era technique with his extremely physical come-ons towards Page, but that could be more due to sexual attitudes of the time than the acting or direction (more on that later).

However, the girls' Uncle Jed, played by an uncredited Jed Prouty (who'd previously worked with director Beaumont in THE GOLD DIGGERS), is an unabashed disaster. With a penchant for mugging and a goofy stutter not unlike Porky Pig's (after a couple of attempts to say something, he'll give up and say something else), he is the same sort of goofy, out-of-place caricature that Larry Semon was in the first film in this column, UNDERWORLD. Thankfully, his role is closer in screentime to Rob Schneider in DEMOLITION MAN than Rob Schneider in JUDGE DREDD.

Wunderkind producer Irving Thalberg, who was already famous for movies like THE HUNCHBACK OF NOTRE DAME and BEN-HUR, declared early on that, "We don't know whether the audience will accept a musical on film. So we'll have to shoot it as fast and as cheaply as we can," (how was he to know that by the end of the 1929, 75 musicals would be released?). Nevertheless, the $350k production came up with a few innovations to help acclimate to the change in the industry.

Back then, the 35 mm cameras they used were really, really loud (think of 35 mm projectors, and then multiply that sound several times over), so to record synced sound, they'd have to house the camera in a little sound-proof booth during takes. Thalberg and director Harry Beaumont helped create a rig so that the camera could move mid-shot, booth and all, so there are some (but not many) brief tracking shots throughout the film.

The film, aside from being MGM's first film with wall-to-wall sound, was also the first to pre-record the music for the song-and-dance numbers; previous productions (like THE JAZZ SINGER) would simply record the songs live, usually in only one shot. It was also the first to commission all-new songs to be written specifically for the film, rather than relying on old standards. The music by Nacio Herb Brown and Arthur Freed isn't life-changing but it's entertaining and cute, particularly the title song. Freed would later reuse several of their compositions from this film in SINGIN' IN THE RAIN, including "Wedding of a Painted Doll" and "You Were Meant For Me".

The film even featured a sequence in Technicolor, making it the first Best Picture winner to do so. A major number entitled, "Wedding of a Painted Doll" was originally filmed in two-strip Technicolor but unfortunately, that footage has been lost. Without the tech gimmick the handsome number, which doesn't feature any of the major players, is something of a distraction from the narrative. I'd sure love to check it out as it was originally presented though.

Inevitably, as with any piece of art from any era that isn't the present, there are some anachronisms that I couldn't help but notice. For one, the whole thing seems tinged by the looming presence of the Great Depression, which would occur later that year. In their first scene, Queenie and Hank openly (in an attempt at relatability) profess plans to steal towels and other merch from their hotel, while purposefully neglecting to tip their bellboy. The whole thrust of the plot involves the two leads fighting tooth and nail to escape their impoverished lifestyles. The "roaring twenties" world of jewels, nice cars, and fancy clothes is so foreign and appealing to them that it's directly responsible for Queenie's desire to leave show-business for the comfort of her sugar-daddy boyfriend. Of course, the rich guys are the dopes and the less-lucky scamps are the heroes of the flick, but that'd been the case since before the days of Chaplin.

I mentioned before that Charles King's Eddie is awful touchy with the Queenie character, but I don't think I can get across just how sexual-harassment-y his behavior comes off as. He stares into her eyes, talks up her beauty, kisses her lips, and basically feels her up, all in front of Hank, his alleged fiancee. His lusty interest in Queenie gets to be real gross; it's even grosser when she starts to reciprocate Eddie's advances.

In general, the way all the guys talk about Queenie reminds me of the male characters in SHOWGIRLS, treating her like a bimbo who's only worth as much as the tautness of her legs and the perkiness of her breasts. When they cast her as a scantily-clad background dancer she protests, "I don't wanna take my clothes off!" and is dismissively told by her costumer, "Ah, that'll be alright." "I've never taken my clothes off in my life before!" "Oh, I know all about that," the man mutters. I'm not saying that modern Broadway producers don't say such callous, cruel things about their talent, but I don't think they are as openly misogynistic and simple-minded as they are portrayed here. Whether it's a product of the times or simply the heavy-handedness of the direction (my cynicism nudges me towards the former), the sexism on display is fairly evident within maybe 10 minutes of the start of the picture.

_large.jpg)

There's also some evidence of the fact that the film was made during Prohibition. There's a bit where a drunken louse tries to offer Hank a bottle at a party; "You don't know what you're missing!" he spouts like he's in REEFER MADNESS. Uncle Jed's goofy response is apparently an attempt at irony: "Why don't you have a little drink, Hank. Might pup you up!" In another party scene a boorish, sloppy drunk approaches Queenie and Jacques. He ignorantly interrupts their intimate conversation, before making an ass out of himself by acting as if he, and not Jacques, were the lady's date.

Afterwards, Queenie returns to Hank in a miserable, over-the-top drunken state, with her slurry dictation obviously meant to accentuate her amoral desire for money and comfort instead of success as a performer. I don't know what bugs me more; the judgmental attitude towards alcohol use, or the consistently awful, cartoony "drunken acting" that many performers were guilty of back then (although I admittedly approve of El Brendel's hammy performance in JUST IMAGINE).

I got a kick out of Hank referencing Babe Ruth, still playing for the Yankees at the time (he hit 54 home runs that season). "Well, we ain't leavin' this town 'til we get a flash with Babe Ruth and Grant's Tomb!" I've seen a million and a half Babe references on film, but none of them while the all-time great was still playing. I don't know, "Let's go check out Derek Jeter!" doesn't have quite the same effect as the prospect of actually going to see Ruth play live, does it?

THE BROADWAY MELODY was made in the pre-code period before 1934, and there's a bunch of stuff that would be scarce in the films that would be made for the next four decades. Almost right off the bat, the two girls get into their skivvies onscreen, with several shots of Queenie nude (shown from the shoulders-up, of course) while taking a bath. There's a hearty amount of sexual innuendos made by both male and female characters, even beyond the ones I've already mentioned. Additionally, the major plot point of Queenie's body being what lands her work would probably be replaced with mentions of her pretty face and her "spunk" a few years later. Hank's lament upon hearing a comment on Queenie's nice legs, "We ain't ever had to get by on our legs before!" doesn't go as far as mentioning the dreaded "casting couches" young actresses were all too familiar with back then, but it certainly points in that direction.

The film was nominated for three Oscars, and won Outstanding Picture, even though Bessie Love lost Best Actress to Mary Pickford (for COQUETTE) while Frank Lloyd, for THE DIVINE LADY (he was also nominated that year for two other films, DRAG and WEARY RIVER), took the Best Director Oscar instead of Harry Beaumont. Even though the zeitgeist has judged the film rather harshly (it has a 38% on Rotten Tomatoes, and was voted number 7 on Complex's list of "The 25 Worst Movies That Won Oscars"), I believe it to be an apt Best Picture winner.

It may not have the most original story in the world, but it certainly laid the groundwork for a great many musicals to come. Most obviously, it spawned the BROADWAY MELODY series, including BROADWAY MELODY OF 1936, BROADWAY MELODY OF 1938, and BROADWAY MELODY OF 1940, not to mention BROADWAY RHYTHM, which was originally titled BROADWAY MELODY OF 1944. None of these films had anything to do with the original plotwise, aside from the shared subject matter of the backstage goings on behind Broadway musicals. There was a direct remake of THE BROADWAY MELODY in 1940 with TWO GIRLS ON BROADWAY, with Lana Turner and Joan Blondell taking over for Bessie Love and Anita Page.

Beyond being substantially influential and groundbreaking, I genuinely like the flick. It has funny, peppy dialogue (when an actress complains to her costumer that her oversized hat won't permit her to make it onstage, he snaps back, "I design the costumes for the show, not the doors for the theater."), a concise, entertaining plot, and an imperfect, but memorable and effective performance by Bessie Love. Sure, I wasn't riveted for every second of the film, but I wasn't for THE KING'S SPEECH or NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN, either. As much technically as structurally, this film set the template for the musical genre that would have a foothold on the studio system for decades to come. Even if it had to be the only Best Picture winner not to pick up any other awards, and without having seen the other nominated films, I'd venture to say it was a good pick.

The Broadway Melody - THE BROADWAY MELODY by ActnTheatre

-Vincent Zahedi

”Papa Vinyard”

vincentzahedi@gmail.com

Follow Me On Twitter