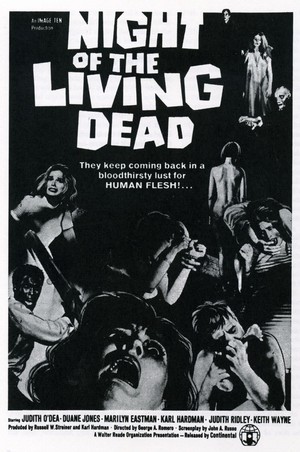

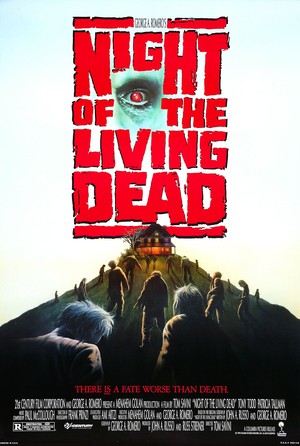

Happy Halloween! And welcome back for another entry of The Doppelganger Files. Today brings a special Halloween treat for you, as I examine George Romero's classic zombie tale Night of the Living Dead, and the remake that Tom Savini directed in 1990.

Night of the Living Dead is, without a doubt, a classic classic film. It’s one of my absolute favorites, and essential viewing around Halloween. With one swoop, George Romero not only created the zombie as we know it (all undead and flesh-eating), but also created an important film that spoke to and reflected the turbulent time from which it came, while, at the same, time, challenging that time period and proving itself a step ahead of its contemporaries.Not to mention a film that terrified audiences for decades.

In 1990, the film was remade with special effects god Tom Savini behind the camera. While not nearly as good as its predecessor, it is an interesting variation on the material. Despite not being as effective, it holds special significance for me because it was the first version of Night of the Living Dead that I had ever seen. I became fascinated with the film when promotional materials appeared in my local video store, announcing its release, and that fascination was only heightened when Lydia mentioned the film’s title in Beetlejuice (she was so cool). I was too young to see it though, and my wishes went unfulfilled for years.

Eventually, I caught it on cable when I was a teenager, and even with a lot of the gore cut out, it still managed to terrify me. Zombies weren’t as prevalent in pop culture as they were today, so the concept was fresh and the impact was intense. The idea of corpses getting up and slowly walking around, finding you and invading your stronghold even when you think you are safe was terrifying. Years later, I would come to know Romero’s original film and find that the one I had grown up with was a pale imitation. But it still stuck with me and was an important part of my formative horror-watching years.

Every time a remake comes around, fans tend to throw their hands up and ask “Buy why?”. In this case, the reason was largely financial - a fact that would normally make me balk, but in this particular case, it made a lot of sense. When Night of the Living Dead was first released in 1968, a glitch on the part of the distributor left the film with no copyright, and it immediately dropped into the public domain. The film was pirated, reproduced and re-released a gazillion times over the years, with Romero, writer John Russo and the entire production company Image Ten not receiving any money for the film that they created. If I had been in that situation, I would be looking for a cash grab too.

So the 1990 film came about as a means of reclaiming some of the money that Night of the Living Dead generated. Romero and original co-writer John Russo came on board as producers, and offered directing responsibilities to Tom Savini. Romero is credited on the screenplay, but was very hands-off during production, advising Savini to make whatever changes he wanted. In the book Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever, Savini describes how Romero offered up creative control of the film: “When George handed me the script, he said use the script as a guide, change whatever you like. If you have any questions, I’ll answer them honestly, but I’m not going to tell you what to do. This is your movie.”

The plot is basically the same - the dead begin returning to life and devouring the living, and a group of people hold up inside a farm house in an attempt to defend themselves. The same characters and dynamics were all present and accounted for, and the plot was more or less the same, with a few (but important) variations here and there.

One of the primary differences between the two films lies in the character of Barbra (Barbara, in the remake). Romero’s Barbra (played by Judith O’Dea) was much more of a passive, unengaged character. After the opening sequence where she barely manages to escape the cemetery zombie, she is pretty much worthless. She stumbles into the farmhouse and is mostly catatonic from the time Ben (Duane Jones) arrives to the end of the film.

In Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever, O’Dea states, “I believe Barbra exemplifies honesty. How she got through her horror ordeal is probably the way many real people would...When zombies were breaking into the house, she snapped back into reality. It was time to fight back. And she did, until her death.”

There is some truth here. Barbra is a character that is overcome by the emotions and the impossibilities of her circumstances. Let’s be honest, not all of us would be able to keep a cool head during a zombie outbreak the way Ben does. Through her stunned silence, Barbra represents the pocket of humanity that would be unwilling or unable to cope in just such a crisis. She doesn’t seem to understand what is happening around her, she replays the traumatic events that brought her to the farmhouse, eventually coaxing herself into a state of full-on hysteria. If Ben represents a human being’s capacity for survival, Barbra represents our defensive self-preservation.

But when Barbra does fight back, it’s more of a defensive stance, fighting because the zombies are swarming her and it’s really the only natural, instinctive response. She doesn’t fight back in the same way that the second incarnation would.

In Savini’s film, Barbara (as played by Patricia Tallman) is much more of a strong, ‘90’s woman. A capable character in the vein of Ripley who, after an initial shock period, stands up and fights back. Sure, she’s a bit of a wimp at first. After escaping the cemetery and dispatching a zombie at the farmhouse, she does go through a bit of a dysfunctional, weepy period where she struggles to understand exactly what is going on around her and how it could even be possible. But rather than falling into a dissociative state and curling up in the corner, she makes a decision for survival, and tailors her actions accordingly. She loses her skirt, finds some boots and begins boarding up the house for the inevitable siege. She even takes control of the gun when the zombies begin getting into the structure. Yes, she goes a little over-the-top with her “I do not plan on losing anything else” line, but the sentiment is right: The chips are down, and it’s time to pony up and fight.

I still enjoy the Barbra character in Romero’s film - there is something rather infectious about her inability to cope, rendering the situation in which the characters find themselves all the more bleak. But, I do think that had Savini tried to recreate that character in 1990, it would have been a mistake. Female characters (especially in horror) had come a long way since 1968. Sure, the genre is still dotted with brainless screamers who only serve as chainsaw fodder for whatever evil is after them, but we also had Ripley. We had Laurie. We had Nancy. We had Alice. An entire era of Final Girls had sprung up in the years following Night of the Living Dead, and they were a well-established part of the horror landscape when Savini stepped into the director’s chair. Barbara was an important change to the film, serving as a way to usher the 1968 film into the ‘90’s and give audiences a character that they were more accustomed to seeing.

Another important difference lies in the racial component that appeared in the subtext of the original film. As African-Americans were not a huge part of the cinematic landscape in 1968, one of the many things that made the original Night of the Living Dead so notable was the casting of black actor Duane Jones in the lead role. The role wasn’t specified for any particular ethnicity, and Romero felt Jones, a classically-trained actor, would be right for the part. But the intention from the start of production had not specifically to make the character of Ben a black man.

And when Jones came on board, the script wasn’t really amended around the presence of a black character. There were a few small changes here and there (he preferred to alter the dialogue away from the intended rough trucker-speak that was written and make Ben an educated man), but the story stayed the same, not noting or referencing Ben’s race at all, which made specific moments of the film particularly noteworthy for the time period. Like the fact that when Barbara suddenly finds herself trapped in the farmhouse with a black man, she isn’t afraid of him. Or the fact that Ben is just as strong and competent as any of his white counterparts in the film, and is even portrayed as our hero. Within the story, the character’s race didn’t play a large role in the proceedings.

Outside the story, on the other hand, the impact was different (and quite interesting). America was going through a particularly racially-charged period, and thus, everything carried weight, regardless of intention. Scenes and actions that had once seemed benign could now be seen in a more racially-charged context.

In the documentary, Birth of the Living Dead, Romero stated that on set, Jones was particularly sensitive whenever Ben was called to act violently because of the racial implications that were involved. He didn’t want himself or the character to be seen as the “angry black man” or to be demonstrating “black rage.” Romero would counter the concerns by stating “that was in the script before the character was black”, arguing that it shouldn’t really make a difference. Jones would retort “yeah, but he IS black now,” hammering home the racial implications of the scene.

It was a valid point, and something that certainly rings true when you examine the film against the political and social unrest of the time period. What was (and still is) a simple story about a group of people taking shelter in a house to escape the threat surrounding them, now carried a certain amount of racial awareness and thematic complexity.

An example example lies in the the scene near the beginning of the film, where Ben and Barbara (a black man and a white woman) are alone in the farmhouse together.

Says co-writer John Russo in Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever: “And then she falls into his arms. And I know that a lot of the bigots in the country are going to be thinking, ‘Oh my God, now what’s he going to do? He’s got this white woman in his arms,’ and lays her down on the couch and he unfastens her coat...and so I was aware that it might have those kind of vibes.”

While nothing is expressly called out, the continuously escalating conflict between Ben and Cooper over where to station themselves and how to best defend the house can be read as having racial undertones, with Cooper not liking the fact that a black man is telling him what to do.

These racial implications weren’t a part of Savini’s film. While racism certainly wasn’t gone by 1990, conditions were different enough that audiences were no longer surprised by the presence of a black actor in the lead role of a film, so many of the aspects of Romero’s script that carried a slightly different meaning or relevance to American culture in the late ‘60’s no longer held the same weight.

Instead of a reflection of a racially-charged culture, Savini altered his film to be more of a reflection of society at large. Some of the imagery at the end of the film (zombie bonfires, lynchings, etc.) certainly harken back and pay homage to the original film and the way it impacted society at the time. But Barbara’s line upon witnessing people engaging in these acts serves as an indictment on the entire human race. “They’re us. We’re them, and they’re us.”

This was particularly reflected in the changes that Savini made to the end of the film, and to Ben’s fate. Romero’s film ended with Ben surviving the night alone in the basement, and, upon emerging, being shot by a group of zombie hunters from outside the house. This ending was shocking first, for having our hero suddenly and unceremoniously killed at the end of the film, and secondly, because that black character was killed at the hands of a group of gun-toting white men, it plays as a racially-charged scene as well.

In Savini’s film, Ben (played by the always awesome Tony Todd) retreats to the basement, only to die of his wounds during the night. The surprise is that when Barbara returns to the farmhouse with reinforcements as promised, she is too late, and Ben has become one of the undead.

So rather than the harsh irony of seeing a perfectly human Ben being struck down by an ignorant, trigger-happy mob, he becomes one of the monsters, and as we are left with Barbara and the remaining humans, we are instead confronted with the harsh truth that we are really no better than the creatures beating down our doors. We spent the film watching zombies kill and eat our human characters, but doing so blankly, without remorse or pleasure. The humans, on the other hand, were deriving a great deal of pleasure from hunting down and killing the remaining undead, even turning it into a series of games and events while they watched and cheered each other on.

Ultimately, the 1990 film is merely a shadow of its predecessor. So much of what makes Night of the Living Dead such a powerful and important film lies in the underlying subtext and in examining it against the events of its time period. Civil Rights...the Vietnam War...rioting and civil unrest...While still a simple story of the dead rising from the grave and feasting on the living, all of these elements were part of the backdrop of the film, and the story as we know it was born of them. It is a brilliant and suspenseful horror film even without taking these pieces into account, but it is these pieces that make the story so much richer. The 1990 film, which strove for cultural significance, is ultimately just a rehash of the zombie story, and little more.

While the filmmakers hoped for the best, the remake proved to be a fairly negative experience across the board - behind the scenes and at the box office. Savini stated, “That was the worst experience of my life...I still have nightmares that I’m on that movie set, directing that movie, and waiting for the sun to come up , so I could just stop shooting and go home.”

The fans weren’t on board either, as the film grossed only $6 million. Says John Russo, “The remake would probably have been a great box-office success if the original had never been made. But it suffers from being compared to the original. The original has the magic that persists to this day, and that level of magic was not achieved by the remake, even though we tried hard.”

Russo is absolutely correct in his assessment. The remake isn’t great, but it’s not a terrible horror flick either. It's bloody, it's scary and it has some decent moments. When examined outside of the original and out of its shadow and legacy, Savini's film stands on its own. Maybe not as tall, but it’s there. It worked on me, sitting in my parents’ basement at 14 with all of the lights turned out. I was terrified to walk through the dark house afterwards, fearing zombies could be hiding in any corner. Sure, the pieces that made Romero’s film important and genius aren’t present, but they don’t need to be for a piece of horror entertainment. It’s still a film that I don’t mind throwing into my DVD player every now and again, both for nostalgia and also for some fun thrills. So if you're looking for something to watch this fine Halloween evening, give one (or both) of these films another look. Perfect for Halloween viewing!

Night of the Living Dead is a film that has a fascinating and rich history.The information here just scratches the surface of its legacy (trust me - I could have gone on for days), so if you're interested in learning more, I highly recommend the book Night of the Living Dead: Behind the Scenes of the Most Terrifying Zombie Movie Ever by Joe Kane, and the new documentary, Birth of the Living Dead, directed by Rob Kuhns.

And if you have any suggestions for upcoming editions of The Doppelganger Files, feel free to send them my way.

Follow me on Twitter