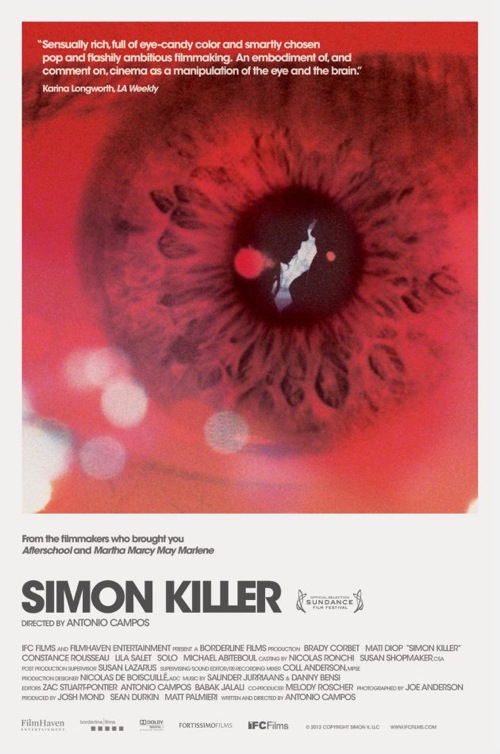

Antonio Campos's SIMON KILLER may appear on the surface to be yet another portrait of a socially-awkward loner on the verge of full-blown psychosis - and, if viewed strictly on that level, it's probably the best film of its kind since Lodge Kerrigan's KEANE. But as with his magnificent debut feature AFTERSCHOOL, Campos is after more than a downward-spiral character study; when you consider that his protagonist (played by Brady Corbet) is a heartbroken young American knocking about Paris, working through his girlfriend issues and fucking up the lives of random people in the process, the metaphorical implications become more and more fascinating. True, Campos may not be the first director to make this observation either, but he gets it across with such breathtaking formal precision that it all seems dazzlingly original. It's the most invigorating film about a profoundly damaged individual you're likely to see this year!

SIMON KILLER is the third feature from Borderline Films, the production company formed by Campos, Sean Durkin (writer-director of MARTHA MARCY MAY MARLENE) and Josh Mond. These talented young filmmakers (all in their early thirties) obviously have a taste for dark, unsettling material, and, if their recent first-look deal with Fox Searchlight is any indication, it's not exactly scaring off would-be financiers. But it's worth noting that SIMON KILLER, made prior to Broderline's studio engagement, is being distributed by the slightly more adventurous IFC Films. After spending a couple of hours with Corbet's erratic college grad as he insinuates himself into the life of a Parisian prostitute (Mati Diop), you wonder if Campos will be able to push this far with the backing of a major studio.

I chatted with Campos about his filmmaking process during last November's AFI Fest, and found him to be incredibly confident and articulate about his artistic choices. Though SIMON KILLER was made without a locked screenplay, Campos gives off the impression that the production was an invigorating challenge; he stresses the importance of problem solving, and seems grateful he was working with two actors who've made films of their own. This is also Campos's second film to be shot in a widescreen ratio (AFTERSCHOOL was anamorphic), so we talked a bit about the cinematic nature of that format, and how, depressingly, it might not be worth the trouble anymore. I hope he reconsiders (there aren't many filmmakers out there who know how to fill a widescreen frame), but, thus far, his artistic instincts have been damn near unerring.

Mr. Beaks: As with any first-time filmmaker, the second feature is fraught with expectations. Are they going to expand on the first movie, or go off in a completely different direction? How did you approach making a second film?

Antonio Campos: It was a very organic process. I found a story that I really wanted to do, and I wanted to do it in a very specific way, without a traditional script. We found an investor who was comfortable with that idea and supported it. Josh [Mond] went out to Paris, and they started putting together all the locations. I was aware of what I was doing in AFTERSCHOOL, and I was interested in still being true to myself and what I wanted to do, but also to explore another universe, and do it in a way that was a different approach to a similar end. I wanted it to be controlled and formal, and I wanted to use improvisation to arrive there, which was very different than AFTERSCHOOL. That was scripted. That said, on AFTERSCHOOL, I was always open to anything that happened in the moment or any other idea that came up on the day.

But there were things I was conscious of from AFTERSCHOOL. I was conscious of the fact that I'd used technology so much and in a certain way. I was interested in kind of avoiding technology on SIMON KILLER - and while it's still part of the story, I don't treat it the same way. I was also interested in continuing this sort of dark character study, and I found an author, Georges Simenon, who spoke to me. There wasn't anything of his I wanted to adapt, but I was very moved by his stories, and there was a character that was speaking to something I'd started to do with AFTERSCHOOL, and that I wanted to go further with. So many of the films that I made when I was younger, up until AFTERSCHOOL, were about young people in some way. SIMON KILLER is about a young person, but he's in his twenties; he should know a little better. There are so many things that were similar, but many things that were different. It was a nice, easy transition for me. There were things I'd already dealt with, but also a whole new kind of palette and world. AFTERSCHOOL is a very... kind of cold film. There are elements of SIMON that are cold at the beginning, but then we go into this lush night world. These books and these films that I love, they're lonely characters, loner characters, and I just really like going on journeys with loner-type characters. And Pigalle was exciting to me: the brothels, the hostess bars, and these women we were meeting while we're there.

But to your question about a second film, I spent so long between AFTERSCHOOL and SIMON KILLER. You just don't know what you're going to do next, then you have an idea and it feels right. We were lucky enough to be able to follow it. Definitely Josh's drive was important. We were in this mode of "We've got to keep moving!" Brady and I worked very closely on the story, and then we worked closely with the casting; we met all of the actors together. It was a very organic process, different than AFTERSCHOOL. But there's nothing like your first film. The way your first film gets made, the way you write your first film, all of these things are unique to that movie. I don't think you could replicate it if you tried.

Beaks: Is this because you'd been thinking about AFTERSCHOOL for a longer period of time than SIMON?

Campos: Yes, that's one of the things. MARTHA was years of gestation, and AFTERSCHOOL was about the same. I had the original seed when I'd finished high school, and 9/11 happened. And a good friend of mine, who had graduated, died in a weird accident in the Netherlands. There was this seed of an idea, and over the years the world changed and my perception of things changed. It was a long gestation period. I was growing, and getting to a place where I was ready to make a movie, that movie. That's the other thing: sometimes you don't make a movie at a certain point because you're not ready to make it, and sometimes that's not decided by you. It's these weird Movie Gods. (Laughs)

Beaks: Or practical considerations like financing.

Campos: That's always a consideration. We're very realistic about what we can do with what we have. We conceive of our films thinking about those things - whether it's in the forefront or not, it's always something we're talking about. Because we rotate as directors and producers, we know the other side of it. We know how hard certain things can be. We've kept the budgets low on our first films so that we can take more risks. Financing isn't easy. We had a financier, Matt Palmieri, he was one of the producers on this and the [executive producer] on MARTHA; he gave us money to finish up MARTHA when we needed it at the very end, and he agreed to put up money for SIMON. He put up money without a screenplay, which is unheard of. And then Josh has a drive and passion that instills a mentality of "There is no other option but this happening."

You need that force, and then you, as a filmmaker, need to believe. Going on the set and not having a script for the day, just having a notepad with five lines of dialogue as the scene, it requires a certain kind of faith that this is going to work. That's the most exciting part of the process: when you know that all the odds are against you, and you know this is fucking crazy. (Laughs) It's a thrill to have to figure that out and be creative. Filmmaking is not everything going smoothly; real filmmaking is problem solving. I don't know what I'd do if it was easy all the way through. It wouldn't feel right. If it's easy, that would be a problem. That doesn't mean you shouldn't be responsible. We always make our days. That's one of the things we pride ourselves on. We make our days and we treat everybody right, so you have respect for the process. What's great about the process is, if I have a problem in real life, I could mull on it for days and days. If I have a problem on set, I have ten hours to figure it out, and I have to figure it out. I like that about making movies. There's order to the chaos. In day-to-day life, you're like, "Oh, I'll deal with it tomorrow."

Beaks: You talk about always making days. Do you have an idea each day of what you're willing to settle for?

Campos: No. You don't ever say you're going to settle for anything. You have to get it right. But getting it right doesn't mean you're going to get shot one, two and three. Getting it right might mean, "We got it in shot one, forget about two and three." Or it might mean "Forget about doing shot one the way you want to do it. Instead of doing a static camera, it pans back and forth." You're creative to arrive at the same end, which is getting the best stuff possible and hopefully bringing out the best in everybody around you. On SIMON, we had a very specific schedule based on the outline, and I was writing as we went along. Some days we were very clear and scripted, some days we're not. Some days I was rewriting in the morning coming to set, then coming to set and translating the script on set with the actor. It was a very complicated process, but we figured out a system. If the actors didn't get a script that night, they knew they'd have it in the morning. They knew that part of learning the scene would be translating the scene with me. It was a great process. Exhausting, but it was good.

Beaks: Given the frank sexual nature of the film, how important was it to have your two leads - particularly Mati - as a part of the story process? From there, how did you make the actors feel comfortable on set during these scenes?

Campos: It was really important that the girl's voice be as heard as the boy's voice in terms of the creative process. Mati came in later in the process, two weeks before shooting basically. We had a hard time finding that character. She's a filmmaker herself, and so is Brady, so they speak that language, but they're also committed to the performance, which is important. It was important to me that everybody felt comfortable and felt that, even if they're only onscreen briefly, that their character had some depth, that there was some complexity.

Beaks: It doesn't feel like a male-dominated perspective.

Campos: Sometimes I feel that people think of the film as incredibly misogynistic, and I say, "No, it's not."

Beaks: It's not like you're advocating his behavior.

Campos: Exactly! That's the thing. Somebody asked me after Sundance, "We didn't know if you wanted us not to like him." And I said, "What do you mean? What did you think about him? Because whatever you felt about him, you felt about him. If you liked him, you liked him. That's your thing, not mine." (Laughs) As despicable as his behavior is, he's incredibly charismatic. You can feel bad for him. You can. There's something that he's struggling with, and he hasn't figured it out yet. The things he does you can't justify, but he's going through something. You go along with the journey, and if you feel bad sometimes, it's because you're like, "Oh, I thought he was somebody else." Well, just imagine what she feels. (Laughs)

Beaks: The dissolves you employ here are very interesting, as is the strobing, which reminds me a little of what Gaspar Noe does. What was your thinking behind these effects?

Campos: Those effects are there, but they don't last for long. I like for those things to linger in your memory. In writing the outline, we had placed what we called "interludes", but we didn't quite know what they were. I knew I wanted to capture something of the mind's eye, and I found that when you shoot the camera without a lens on it, just sensor exposed to light, you get this beautiful... flare, I guess. There would just be shapes and colors. So we started experimenting with different colors, different kinds of light and different shutter angles. Then we found that we could run a regular light past the sensor, but if we ran a regular light and the LED, if the shutter was at a certain angle, then one would strobe and the other would be normal. There's something about the imagery, as I was seeing it, that spoke to me, and reminded me of being a child and pressing my hands against my eyelids to see colors. There's something about Simon that seems like he's so in his head, that the strobing and colors spoke to me.

Beaks: What about assembling Simon's playlist, and then deciding when to drop out of his head and present us with the ambient noise of the museum? What was your thinking behind that?

Campos: After AFTERSCHOOL, everybody expects me to be stark and use no music, so I was like, "Let's just do tons of music." If a scene ends... we'll just cut it. We're going to be in his head. That way, Simon is controlling the soundtrack in the same way that Robert controls the frame a lot of the time in AFTERSCHOOL. I like this idea of a character as a part of the texture of the film, that how it looks or sounds is directly connected to what the character is doing. We knew that we wanted Simon to have his headphones in all the time, so we put together a list of all this pop music we love. Brady has an extensive knowledge of indie music and avant-garde music, and I've got my list of things I like a lot. And our music supervisor just did an amazing job at giving us a ton of options. We couldn't get everything we wanted, but we got a lot. And thanks to Josh, we met LCD Soundsystem. We met James Murphy and [music manager] Brian Graf. Those guys were great. Really wonderful and generous to us. We just had really good options. We were trying to use Lee Moses's "California Dreaming". They used his music in Bonello's HOUSE OF PLEASURES. I'd been listening to Lee Moses for a year before that, but we could not afford "California Dreaming". So I found two other tracks through Numero Group, which basically licenses all this amazing music from the '60s and '70s, except it's more obscure stuff. We found these really great tracks, and this soulful quality of music spoke so much more to Victoria [Diop's character]. There was something about everything Simon was doing next to this pop score. And then the score is basically trying to fill in a certain kind of audience response. We were approaching it in a sort of primal way. We wanted it to be stripped down and as simple as possible.

Beaks: There's a political metaphor floating throughout this movie, just as there was a 9/11 metaphor running through AFTERSCHOOL. In this, you've got an American in Paris, he knows just enough French to get along, he seems to come from a family that's well off, he puts his first session with Victoria on credit, and she has that line at the end, "I was doing fine before you got here." How much are you thinking about that kind of stuff? I don't want you to explain the movie, but I am curious as to how deliberate you are in setting this up.

Campos: I think about it a lot. It's funny... I think about it a lot, and then when the movie's over, I worry that no one noticed. On AFTERSCHOOL, I was really worried that I'd gone too far with it. With the twins, and "never forget" and "always remember". In the final speech Michael Stuhlbarg gives, I had taken lines from speeches at that time. I'm always thinking about this, and I really like the idea of using character and story to explore big ideas, ideas that are so big that you don't immediately associate them with the story. I'm always thinking about that stuff. They definitely don't need to notice it to go on this journey, but it's there.

Beaks: A lot of young filmmakers like to shoot widescreen, but I feel like most of them don't know how to compose for it. You're very adept at it. Is this your look? Are you going to stick with it?

Campos: I like composing for that aspect ratio. There's just something cinematic about it. That aspect ratio is kind of the last remnant we have of cinema. That said, I wonder if I'm going to shoot the next film in 2.35 because of the pan-and-scan process. You end up having to butcher the film at some point, and it's frustrating. If people are just going to watch the movie on a plane, why not just compose it for that? Kubrick dealt with that a lot. All of us Kubrick fans freak out about aspect ratio. "Am I watching this in the right aspect ratio right now?" And no one ever gets it right. I'll be watching THE SHINING and enjoying THE SHINING, and then I'll be like, "Wait, this can't be right." And then I've got to go back. I just want there to be some uniformity to the thing. 16x9 isn't bad. Sean and I would have this thing on both MARTHA and SIMON, where we'd click out of the widescreen. AFTERSCHOOL was anamorphic, so that was what we had - which is great because you're locked into it. But when you shoot full frame, and you've got all the information - which is great for later, adjusting frames and hiding things you don't want people to see. But sometimes you look at that full frame and go, "Oh shit. There's a whole other world there." There was something about these first two films that had to be 2.35. I wish I could go 4x3, but you can't do that either.

Beaks: Well, Kelly Reichardt did it with MEEK'S CUTOFF. And Andrea Arnold uses it. She says it's great because a frame of film is a square.

Campos: The best aspect ratio... (Pause) a landscape should be 2.35, a close-up should be 4x3 and a two-shot should be 16x9.

Beaks: Although Leone did wonders with extreme close-ups in widescreen.

Campos: You find a way of doing it in your medium. Everybody's definition of a close-up is different. You find what a close-up is to you. For me, they're fighting with the frame.

Beaks: Was there a film that blew that wide open for you?

Campos: Bergman taught me a lot about faces and the power of just watching someone speak. That was a revelation to me. Something like PERSONA and looking at Liv Ullman. Or WINTER LIGHT, where [Ingrid Thulin] tells that story to Gunnar Bjornstrand. Those moments of just people sitting and talking, and the power of their face, and how they can hold the frame if the acting is good enough. Kubrick changed everything for me. That's the problem: Kubrick did it all and did it right. There's something very painterly about the way he did it. And Spielberg was the first person that put in my head that you don't go to a close-up unless you really need to go to a close-up. Close-ups are very precious things. Don't overuse them. When Spielberg first started doing television, he wanted to do everything wide, and they were like, "What's wrong with you? We shoot everything close." I remember that story vividly. It makes so much sense to me. If this is the scene, why not shoot it unless we need to see a tear or some gesture.

Beaks: Spielberg skips back and forth between 2.35 and 1.85. I asked him if he had a philosophy for that when he did press for LINCOLN, which is 2.35, and he said simply, "With LINCOLN, I just had to fit a lot of characters in the frame."

Campos: It's true. Sometimes that's it. I spoke to Robert Altman once in my life, and I asked him for advice. I was eighteen or nineteen, and I was like, "What do I do if an actor's not giving me the performance that I want?" He said, "It's not you on camera. If you can't get it, you can't get it. All you can hope for is that you have somebody better to cut to." That was the most honest and practical advice: just have someone better to cut to, and you'll figure it out in post. Sometimes the most practical advice is the truest.

Beaks: Is there a sort of unified aesthetic you're going for at Borderline Films?

Campos: No. I think people will draw comparisons because we're all working together, and there is something that binds us as filmmakers. But there's no aesthetic, no dogma.

Beaks: Thematically perhaps?

Campos: We're all interested in dark stories, but we love different kinds of movies. It's just that, so far, these are the films we've been making. The thing that connects them is that all of the characters are lost in this process of trying to figure themselves out. That'll probably be true of Josh's film, too.

Beaks: Do you have any studio aspirations?

Campos: We have the deal with Fox Searchlight.

Beaks: What about big Fox?

Campos: Big Fox? (Laughs) I just want to keep making movies. I want to make big movies. But I don't think we've ever made a small movie; we've just worked with small budgets. If we ever have the luxury of working on a bigger scale with lots of money, I would love that. But at the end of the day, we always make an effort to never make them look like small films - and to us, they're not small films.

SIMON KILLER opens Friday, April 5th, in New York City. It will expand theatrically and make its VOD debut on April 12th. Don't miss it.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks