Ahoy, squirts! Quint here. When the offer to visit Laika Studios came through I was freshly home from my nearly 3 month New Zealand excursion. On that particular trip I flew or drove somewhere around 70,000 miles (that’s a conservative estimate, by the way) in one three month period, at least half that travel happening in one 7 day period.

So, you’d have to imagine that me and travel were pretty much done by the time I walked back through my door. In fact, I told Harry in advance that I was taking 10 straight days off, the first such vacation in all my 16 years at Ain’t It Cool and I spent that time blissfully not moving on my couch, purring kitty on my lap as I vegged out, killing asshole dragons in Skyrim.

When the offer to travel to Portland and visit the stop-motion set of ParaNorman came in, the slothy part of me wanted to ignore it and stay home forever, but the nerd-brain sparked to the thought immediately. As big a fan of stop motion as I am, I’ve never been on a stop motion set and it was just something I couldn’t let pass.

Today’s late teens/early twenty-somethings don’t remember, but in my era stop motion was king. Maybe not in features, but in every other aspect of my daily pop culture intake. From the California Raisins to my favorite scary movies (Randy Cook’s work in The Thing and The Gate come immediately to mind) to the old movies that would be on a constant loop (Harryhausen!) to all my favorite shows, like Pee-Wee’s Playhouse… there was no escaping that aesthetic.

Now stop-motion animation (or stop-frame as they prefer to call it) is eschewed for CG, but thanks greatly to the work done by Tim Burton, Henry Sellick and Laika it’s more viable than ever as a feature animation format.

You guys know my affection for hands-on effects, so it shouldn’t be a surprise that I was able to lift myself out of my nearly (blissfully) vegetative state and braved the wide world of travel once again to go see some masters work at their craft.

This write-up comes a bit late in the process and I apologize for that. Technical difficulties and personal life silliness got in the way, but it was a fascinating trip and I hope you guys enjoy the report.

Laika, if you don’t know, is the company that put together Coraline. Their animators have worked on everything you can think of. James and the Giant Peach, Nightmare Before Christmas, The Corpse Bride, Fantastic Mr. Fox, etc. They’re the Pixar of the hand-animated world (I know that’s suspiciously close to hand drawn-animation, but you know what I meant).

The level of detail, artistry, sweat, time and tears that goes into one shot in a film like this is staggering and I didn’t realize just how staggering until this visit.

But we’ll get to that in a minute. First thing that happened on this visit was a screening of some rough scenes from ParaNorman.

Now, I’m sure most of you have had the chance to see the film yourselves by now, but if you haven’t it’s about a little kid that loves horror, isn’t particularly popular and can just happen to see and speak with dead people.

He lives in a small town with a big curse and finds himself in the middle of a zombie uprising as a century’s old witch’s vengeful curse reanimates her puritanical pursuers. Of course Norman is slightly ahead of the curve on this one since paranormal occurrences are old hat for him, so it’s up to this young geek and his buddies to take action.

The footage was very rough, rods holding the floating (read: ghost) puppets could be seen, color wasn’t timed, sound wasn’t mixed, etc, but it did establish the playful family horror tone that I loved growing up in films like The Watcher in the Woods and Something Wicked This Way Comes. It’s not as dark as those films, obviously, but embraced the Halloween holiday spirit.

A particular stand-out was a scene in which Norman wrestled with a corpse, but that needs a little bit of set up.

The boy is confronted with the news of Mr. Prenderghast’s death. Mr. Prenderghast is a huge flannel wearing goofy lumberjack of a man voiced by the great John Goodman and Norman finds out about his death in an odd way… he gets a visit from Prenderghast’s ghost... while in the toilet.

Turns out this not-quite-there man was very much like Norman, could communicate with the dead and was the guardian of a special book. His ghost shows up to pass that burden off on this kid.

Unfortunately that book is in the clutches of Mr. Prenderghast’s corpse and the corpse doesn’t seem to want to let it go. So, what follows is a comically exaggerated version of the opening shot of Young Frankenstein that ends up with the giant corpse on top of Norman, its tongue rolling out and onto the kid’s face, much to his great horror.

It was actually really funny, but then I think creepy giant corpses accidentally tonguing children is kind of awesome. I’m weird that way.

We saw lots of little moments, including Norman being consoled by his dead grandmother and it all looked fine, but what really got me excited about this visit was getting to a firsthand look at the production of a major stop-frame animated movie.

On Coraline they pioneered a new process using 3D printers to create thousands of faces that can slip on to the puppet that covers all expressions, mouth shapes and the transitions between the two. This is actually an extension of the process Henry Sellick’s team used on A Nightmare Before Christmas, but with many more transitional pieces to smooth out the lip syncing.

For ParaNorman they’ve advanced that technology even further. On Coraline the 3D printer would construct the faces, which would then have to be hand painted. It’s beautiful work, but limiting. The example directors Chris Butler and Sam Fell gave is that Coraline had 6 freckles because they had to be hand painted every single time. There’s a character named Neil in ParaNormal who has thousands of freckles because of a new piece of technology that not only creates these thousands of faces, but paints them as well.

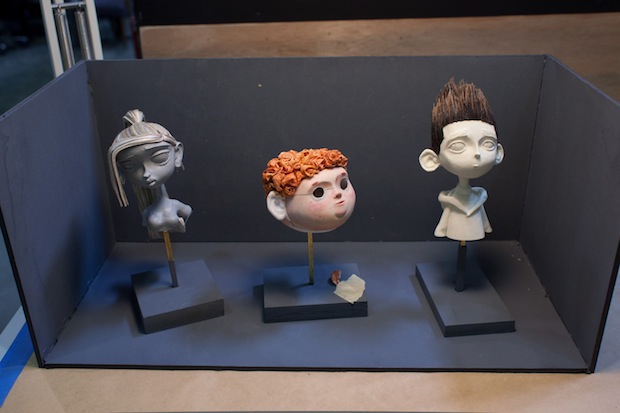

Here’s freckled Neil:

All the characters are based on hand drawn artwork by Heidi Smith and are then taken into Maya, the long favored CG animation program by the industry’s top artists. From there, the original 2D designs are adapted for a 3D world and each character is painted in the computer. That information goes to the Z-Corp650 3D printer, which is filled with a floury white powder that the machine then turns into hard plastic 3D “print-outs” from the 1s and 0s fed into it.

What comes out looks like this:

If any of this is confusing to you, here’s a bisected look at Norman’s head to show you how the face fits on over the eyes:

As you can see, there’s a specific feel for the human characters in this film, but they also used the more traditional puppets for the zombified judge characters.

These guys have access points in their heads where an Alan Key can manipulate the interior mechanisms to pull faces, etc. It was a style choice the filmmakers made in order to make the zombie characters stand out from the human guys.

The amount of work that goes into a stop-frame feature like this is mind-boggling. We toured the animation floor, which is essentially a giant Raiders of the Lost Ark warehouse space with massive black curtains hung throughout, concealing cubes of space. In these curtained off cubes were animators rehearsing or filming specific shots. There are over 40 of these areas working at the same time, each with an animator working on a specific shot.

Now these big spaces were filled with massive sets. As impressive as the puppets were, seeing these sets was another level. True bigatures, these streets of suburban houses, complete with Autumn leaves scattered on the sidewalks and lawns, were ridiculous. I can’t even begin to imagine the kind of attention to detail and talent that it takes to build these things.

We stopped in on one guy doing the shot in the film where Norman rides his bike up to Mr. Prenderghast’s house, skids to a stop (you know the shot even if you haven’t seen the movie… a kid rides a bike, hits the brakes, the rear tire swinging right up to the lens, etc), dismounts and cautiously walks up to the creepy house.

The animator was rehearsing the shot, animating only every other frame which gives the directors a jerky, but accurate representation of the shot for them to give their notes on. Already they had decided that Norman needed a little more exertion when pumping the pedals up the hill. The rehearsal takes 10 days and the final fully animated shot was estimated to take about 22 days… all for a simple shot of a boy riding a bike that lasts about 8 or 9 seconds in the final film.

Now you understand why they need 40+ units simultaneously working on shots. If they had one unit working it would approximately 579,791 years to make one of these movies. That’s just math.

For some of the more complicated shots, like the puritan zombies rising from the grave, the animation takes even longer. Travis Knight (producer, head of Laika and also their senior animator) spent a year animating that sequence.

For you more filmmaking literate folks (I’d wager most of you reading this), you might wonder how they keep continuity having so many of these units spread out and running at once. It’s a legit question. Each animator has their own X sheet, a list of what faces need to be on each puppet in which frame. You see, they figure out in advance how many frames it takes to get from one facial expression to another and make a handy list for the animators to tic off one by one as they stop-frame animate their way to a finished feature.

Cinematographer Tristan Oliver (Fantastic Mr. Fox, Chicken Run) also floats between units, making sure the lighting matches for what is intended (with the help of 4 lighting cameramen as well) and that it all matches up in the end.

And make no mistake, they lit these sets like they would a feature film. It’s not one of those things where they just add backgrounds in post. I saw Travis Knight (Laika’s owner, remember?) animate a scene from the end of the film that takes place is a gorgeous, sunset-hued forest and the massive room was all orange and yellows.

A ton of love to all the wonderful CG artists out there, many of whom provided crucial components to this particular film, but there’s something to seeing artists working with physical puppets, really-there sets and bending actual light that is incredibly striking to me. The Pixar guys are fantastic and the atmosphere of their workspace is incredible, but it’s a wholly different experience seeing someone make a doll come to life than it is seeing someone sitting at a computer dragging and dropping textures.

That’s not to belittle the hard-working CG animators out there. They do God’s work and are no less artists than those working with puppets, I’m just programmed to react much more strongly to seeing real life assholes-and-elbow-grease hand-made figures transformed into a living, breathing characters. That’s real movie magic to me. It’s the way I’m wired.

It was fantastic getting a glimpse at the daily routine of Laika as they make one of their films. I knew I liked the aesthetic going into this visit, but I think I had a naïve understanding of how something like this came together. I knew it was a lot of work, but knowing that and understanding that are two very different things. Films like this are a long, slow, meticulous grind, but the results are always worth it. At least for lazy old me who just gets to sit back and watch the final product.

I’m going to leave you with a ton of ParaNorman BTS images. Hope you enjoyed the article and the little peek inside Laika. Here are those pics!

-Eric Vespe

”Quint”

quint@aintitcool.com

Follow Me On Twitter