When we first see Jacky Vanmarsenille (Matthias Schoenaerts) shooting himself up with anabolic steroids, the sense is that he's some kind of bulk-obsessed juicehead. As we watch him move through the crooked world of the Belgian cattle industry, he becomes a frightening creature: immense, inarticulate and volatile as a truckload of nitroglycerine. He's primed to explode. But even before we learn why he's transformed himself into a true raging bull, we feel for the beast. Jacky seems helpless and heartbroken. Someone made him this way.

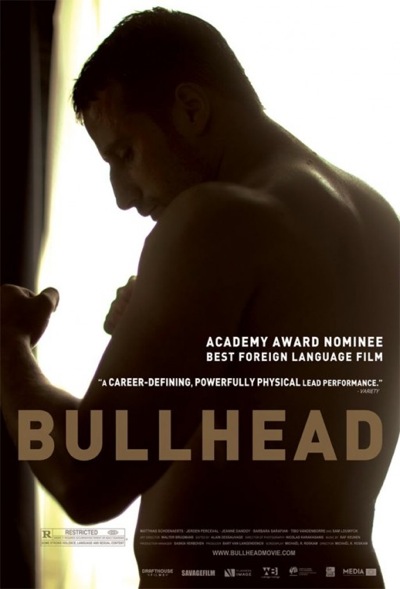

The best-left-undisclosed trauma of Jacky's childhood sets in motion the tragedy of Michael R. Roskam's absorbing debut film, BULLHEAD. On one hand, it is a noir told from the perspective of the muscle. But it is also a procedural that guides viewers through the largely unexplored subculture of Flemish growth hormone trafficking. It is an ambitious, sometimes sprawling film, but Roskam never loses sight of the burly lug at the center of narrative. This isn't a crime film about getting over, nor is it a simple revenge narrative; though BULLHEAD toys with noir conventions throughout, it also owes a great thematic debt to monster movies like KING KONG and BRIDE OF FRANKENSTEIN.

After making a good deal of noise on the festival circuit, BULLHEAD is finally opening in U.S. theaters this Friday. It is also a nominee for this year's Best Foreign Film Oscar, which will be handed out next Sunday. Last week, I had the pleasure of chatting with Roskam, who's finally nearing the end of a press tour that began last February at the Berlin Film Festival. He was fighting a cold, but was still plenty lucid as we discussed the real-life inspiration for his film, the influence of everything from KING KONG to RAGING BULL, and how Bruce Wayne's transformation into Batman parallels Jacky's journey from boy to bull.

Mr. Beaks: I love movies that delve into strange subcultures. Throughout the film, we're learning about growth hormones and how they're used in the cattle industry. How did you get interested in this?

Michael R. Roskam: Because it was there. Let's say one day we woke up in Belgium realizing that a part of our farmers were gangsters using mafia techniques to do business, using illegal growth hormones on a huge scale, and that some of our officials were involved in it. It was a scandal, and it all resulted in the killing of an inspector of the Food and Drug Administration, a veterinarian guy. He took samples out of the animals at the slaughterhouse to see if there were illegal growth hormones in it. He was like this Eliot Ness kind of character; he was going to go for the law. All of the other guys were connected to the mafia; either they were intimidated - like, "We know where your kids go to school" - or the guys in the early stage, like, "I'm going to play the game. I've got access to hormones." They sell them, buy them, and when the cows come in the slaughterhouse, they're like, "They're fine!" This guy didn't do that, and they killed him. Big scandal. And I thought later on when I started to write movies, it was pretty clear that this was such an interesting crime scene. And if you want to do a film noir, you need a crime scene or a tragedy - and that crime scene was there. You couldn't ignore it. I'm surprised nobody did it before me.

Beaks: So that was kind of a SERPICO story. The one honest guy threatening to break up his colleagues' sweet deal with the mob.

Roskam: Yes. I saw immediately the parallels with classic gangster film noir movies from America. By going so local and authentic on my crime scene, I discovered I could use all the same things: destiny, redemption, vengeance and loyalty. I have a femme fatale even, although she's not playing one. She's a femme fatale because [Jacky] allows her to be one. He is falling because of her, and she's not even doing anything. It's my 21st century version of the film noir with my own code, my own interpretation, and trying to make this allegory work. And, of course, every crime scene is a subculture. And every exceptional thing is, in a way, a subculture. The culture is the general thing. What is specific or exclusive is in a way subculture, and that's what we make movies about - not only to expose it to the public, but also because it's a microcosm where you can put all the archetypes of classic drama. For me, BULLHEAD is a Shakespearian tragedy, but an evolution of it. It's a Belgian version of it.

Beaks: I had no idea where this film was going. Watching it unfold, I initially thought it was setting up to be a revenge story. But Jacky isn't out for anything as simple as revenge. And so we get to wander around in his shoes and try to imagine how it is to live like this, and what it is he really wants from life. You engage our empathy.

Roskam: It's compassion. That's what we feel when we're watching KING KONG or BEAUTY AND THE BEAST. We feel compassion for the animal that if we touch it will kill us. That's a very disturbing and almost uncanny feeling. It's like when you go to the zoo, and there's this glass between you and a gorilla. Suddenly, he looks in your eyes and you see a being. And you're like, "Come on over here, you big, great ape!" But the minute you remove that glass and touch him, he probably kills you. Not because he wants you dead, but because he's afraid. Is he guilty? No. Will he kill you? Yes.

I've always been intrigued by the human beast, the animal version of what we think is human. We still have it. We can still kill with bare hands. Culture is important, but [we] just need a little snap or whatever and it breaks open. Then we're back to our very basic behavior. I'm intrigued by this, and I'm not afraid of it either. We will never get rid of something fundamental and basic, which is our instinct. And our instinct is based upon fear and avoiding danger. I like that. That's also why my movie is maybe so dark and violent: I think we should not pretend that these feelings are not there. We should be aware of it, and see it as part of the human nature. Although my film has a certain ending, I always wanted to give some glorifying aspect to it. That's what I see. People walk out of the movie, and they are shaken. They have a very profound experience. In a way, I think most of the people, that's why they like it. They like the darkness. They like the glorifying aspect of the darkness.

Beaks: All these years after the trauma, Jacky is trying to live what he believes is a normal man's life.

Roskam: As a cliche of a man.

Beaks: Exactly. Is Jacky doing this because he thinks it's expected of him or because he actually feels it somewhere within in?

Roskam: I think you have to compare it to Batman. He becomes the trauma. [Bruce Wayne] becomes the bat. He becomes the bully. It's a very basic psychoanalytical archetype. And [Jacky] is imagining manhood as a kid would do. When I had action figures as a kid, they looked like He-Man; they looked like perfect gods of muscle and bone. That's what [Jacky] thinks: "If I'm like that, they'll never attack me again." Like Batman, he knows that if he can be as frightful as a bat, he will frighten the villains. That's what Jacky does. He becomes the man he thinks he has to be so no one will ever attack him again, and at the same time he will become the cliche of the [alpha male]. But it also mixes up his personality. It deranges his personality; it's an action/reaction thing, and that will have to end somewhere.

Beaks: In the telling of the story, did you ever think of keeping it just at Jacky's perspective? Did you think of not shifting to the perspective of the investigator?

Roskam: Even now, I'm kind of surprised that people call it a psychological portrayal of a man. I never really saw it that way. I saw it as a psychoanalytical portrayal as a consequence of telling my story. I wanted to have a whole world. I didn't want it to be a drama. I wanted it to be a tragedy. And to make a tragedy, you need equally important characters. Many of your actions are defined by the actions of others, and I like to give motivation to the others' actions too. Of course, I thought about it, but I wanted it to be classic film noir; the tension and the suspense comes not only from the inside, but the outside.

Beaks: It's difficult to think of this film without Matthias. How much time did it take to get him to completely disappear within this character?

Roskam: I don't think it was ever easy, but I do believe he was perfectly fit to do the part. I knew that from the beginning. We met in 2005. He was part of my short film, and I knew he was the guy to do this. And he gave me confidence to keep writing and developing the character. I knew that I could do whatever I wanted because he was going to bring it to the screen. He was skinnier before. He gained sixty pounds for this part. I told him, "You can't stay like this." He said, "I know. I'll bring it where it has to be." And he started to get obsessed with this image of the minotaur; he was becoming like a bull himself. He trained and worked and ate and did a lot of stuff. I saw it happening, and sometimes I was scared that if I fucked it up as a director that he would've done all of this for nothing. I owed him a good movie. I wanted it to be as good as it could be.

Beaks: There is some emotional linkage between Jacky and Jake LaMotta in RAGING BULL. Like you were saying earlier, you're afraid of him, but you don't ever want to be in the same room as him. Were you thinking about De Niro's LaMotta as you wrote and made this film?

Roskam: Scorsese is a huge influence. When you're a young man and you discover Martin Scorsese's movies, the world changes. You've been growing up as a kid believing that there are only good people and bad people, cowboys and indians, cops and gangsters, good versus evil... whatever. Then you see these Scorsese movies, and you're like, "Whoops! It's not that simple." I thought that was such an important thing to learn, and I wanted to contribute to this tradition. Of course, not only Scorsese did this. Many in literature had done this before him. I want to be part of that tradition. I want to belong to a group of people who do this, who dig into the beasts and the villains and try to find humanity and give it back to the people.

Beaks: What other genres do you want to tackle? Where do you go from here?

Roskam: All the movies that I want to do are going with people who will, for one reason or another, cross borders. They're not what we consider "normal". I like crime movies and criminals. You know why? Imagine a scene: a guy... you don't know what he does. Maybe he works in a bank. I don't know. But he's driving a car, and there's a person crossing the street on the crosswalk. They glance at each other just a little, then the guy keeps walking. The driver waits, the light goes green, and drives off. Now, imagine the same scene where you know the guy driving the car is a gangster, and the two glance at each other. Now you've got suspense. You don't know if he's going to step on it and go through the red light. You're waiting for him to do something you wouldn't do if it was you at that red light. I like that.

BULLHEAD opens Friday, February 17th in New York, Los Angeles and Austin. Don't miss it.

Faithfully submitted,