Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

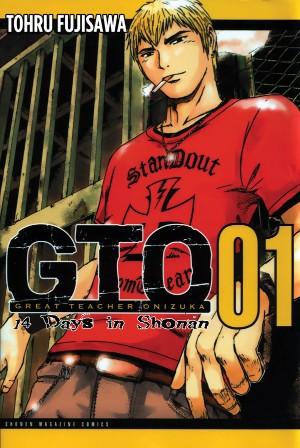

Mang Spotlight: GTO: 14 Days in Shonan

Volume 1

Tohru Fujisawa

Released by Vertical

Six and half years and the death of a publisher later, Great Teacher Onizuka is back in North America.

New publisher Verical also has 1990's 31 volume prequel Shonan Junai-gumi ran, but they're starting with the 2009, 9 volume GTO: 14 Days in Shonan follow-up to 1997, 25 volume GTO: Great Teacher Onizuka.

Besides these, the franchise also include 1997 prequel to the prequel Bad Company , newly launched spin-off Ino Atama Gargoyle - a 1999, 43 episode anime (released in North America by Tokyopop, in the brief period in which they were in the video market), and a live action TV drama and movie for good measure.

As suggested by the fact that it kept the "GTO" prefix, 14 Days in Shonan is more an adjunct to Great Teacher Onizuka than another phase of his life along the lines of the jumps from Shonan Junai-gumi to GTO or back to Bad Company. The earlier series really won over an audience, an in a way that's appropriate to GTO and likely to please fans, it's more of the same, slightly but importantly different.

It's easy to imagine GTO as an insufferable performance to the the back row. It's a formulaic, broad comedy with plenty of sadistical physical humor and gross gags, spicing up the heartwarming story of an unconventional teacher reaching his students. In practice, the manga is certainly low brow and unsubtle, but, crucially, while the manga's hero is a buffoon, he gets it. There's a way in which he and by extension the manga is cogniscent of the social implications of what's going on that gives the manga a sharp edge.

The eponymous Eikichi Onizuka is still the same early twenty-something, unlucky in love, bleached haired teacher who never lost the toughness that made him a biker gang alpha. GTO has always been fast moving, but the early chapters here are Usain Bolt business. 14 Days in Shonan finds him in the midst of a shaggy dog story that distills plenty of the series’ kinetic humor and cringe-inducing social interactions into a quick re-introduction of the less serious elements of what GTO has to offer.

The net is that on the eve of summer break, after reviving the earlier series' gag about defacing the Vice-Principal's prized car (this time he paint Haruhi Suzumiya on it) Onizuka appears on a panel TV show, during which he horrifies watchers with an anecdote about almost burying a student alive under Mt Fuji. The consequence of this is Onizuka is temporarily exiled from Holy Forest Academy and Tokyo, which sends him packing to the stomping grounds of his lawless youth, the bay city of Shonan. There, he finds lodging and purpose as a temporary supervisor at the White Swan Youth Home.

There are many static elements of the original GTO, and these transition into 14 Days in Shonan, except for when they don't. It's still a formula of Onizuka winning over his charges and helping them work through the trauma plaguing them. As, as ever, how that works out, in terms of who Onizuka is, what he does and how he does it makes for some interesting juxtapositions.

On one hand, there's a super heroic by way of broad comedy quality to the character. As Onizuka puts in his resume, his personal merits include an ability to bench staggering amounts of weight, matched with impressive karate credentials. This physical prowess allows him to fall from multi-story heights without significant injury, toss filing cabinets and single handedly tackle gangs of armed trouble makers.

His weakness/comedy enabling flaws include a bit of mental dimness. He's certainly not books smart. He's not terribly street smart of gifted with some great social IQ either - often driven by instinct, he'll make any gaff or walk into any pitfall, especially in service of the often sicko humor.

His second, rather juvenile kryptonite is a perpetual failure to get intimate with the opposite sex. And this one points to just how static GTO can be. The characters strengths and weaknesses are already cooked. Like Fist of the North Star's Kenshiro, he starts offs the king badd-ass. And on the other hand, as close as he might get, the character is never going to consummate a would-be romance. GTO Onizuka will remain a virgin. It seems that Tohru Fujisawa realizes the tricky balance that he needs to maintain as he throws out a stream of crazy ideas and that he is loath to tinker with it. I think about Spider-Man and how Marvel married the characters, then demonically annulled the nuptials. Fujisawa wouldn't have married the character off in the first place.

GTO is career focused, and engaged on actively carrying out a job rather than aspiring to one. For the most part, it's not following a shonen formula in that way. Instead, it borrows, almost wholesale, conventions of salary man manga. From the trouble with peers and superiors with ulterior motives and/or by the books methods to the favorable impression that the heroes forms on a seeming nobody who proves to be an influential benefactor, the pattern is also gleefully conventional.

Where the two formulas clash is that, in a true salary man manga, the hero would climb to new roles and acquire new responsibility - the point of a salary man manga is adult wish fulfillment with the narrative of a person working their way to CEO. But the distinction is important. Onizuka embraces his Sisyphean role, always meeting and helping teens roughly the same age. Maybe there will be a Great Principal Onizuka story some day, but expect it to be a jump rather than a gradual development depicted on page.

Still, the institutionalness of the salaryman story is key to the original GTO. For all of his stupidity, Onizuka gets it. He debunks the notion of things being the way that they're supposed to be, specifically, the prescription that you keep your head down, plow through school, do what you need to, and if you stay focused, comfortably arrive at adulthood. The character as much as explicitly says that if that blueprint was never valid, it was shredded by the end of Japan's boom economy and its accompanying promise of lifelong corporate employment. As our hero contends, grinding young people into neat, orderly followers is now way to prepare them for modern adult challenges.

At the same time, GTO makes the stakes clear. Onizuka's vice-principal nemesis buys into the conventional system, and its unmediated dedication to career costs his relationship with his wife and daughter. Other adult characters who cause or exacerbate the manga's problems serve as examples of what the broken system produces. Most of their hang-ups and kinks are maladjustments stemming from their teen traumas.

14 Days in Shonan rings all the bells you'd expect from GTO. Onizuka stomps the hell out of a huge, abusive parent, gets into a physical altercation with the police and several altercations with gangs of tough organized to take him out of the picture. And, on the sicko side of the equation, there's a string of gags with cockroaches and their consumption. Clearly 14 Days is finding the space to entertain in the fashion that GTO readers have come to expect.

The difference between the original GTO and 14 Days in Shonan isn't entirely subtle. Now, the often gross-out, often over the top earlier GTO wasn't exactly low key. Onizuka's students were drugging, stripping and stabbing each other, but they were also in school, in uniforms, and in theory able to pass for being well adjusted. Here, the characters are more overtly from severe circumstances. It's pretty unignorable. For example, one of them was forcibly tattooed. As such these teens have been flagged by society as endangered. As a character explicitly points out, it's painfully evident that parental selfishness has given them severe reason to distrust adults and that they're not about to give Onizuka a second chance if he lets them down. As a result, the manga is dealing with the same Onizuka, but watching him walk a much narrower tight rope.

The distinction between working with a flawed attitude towards education and flawed expectations and working with teens who have been profoundly traumatized by parental abuse or neglect is one that Tohru Fujisawa is sure to recognize and work with. For all of the manga's acute unsubtleness, it's intriguing to consider how the manga might react to the new twist in its careful balance act and how 14 Days might consequently develop in subtly different ways than the original.

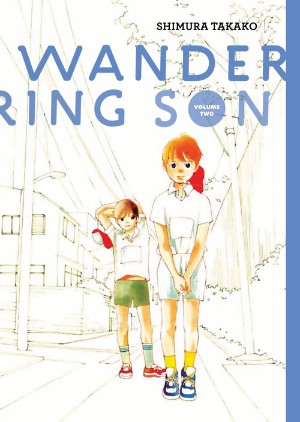

Manga Spotlight: Wandering Son

Volume 2

By by Shimura Takako

Released by Fantagraphics

Wandering Son tracks the formative years of six grade Nitori Shuichi, who wishes he was a girl and his friend Takahashi Yoshino, who wishes she was born a boy. It's a measured, sensible and sensitive series that runs in Comic Beam (still ongoing after 12 volumes), an alt seinen (ostensibly older male audience) anthology that describes itself as "a magazine for comic freaks!"

When a magazine for younger reader features manga with older characters, the reasons are usually pretty obvious. It's rarely difficult to spot the wish or interest in the adult world or realized potential that it's dealing with. In the inverse, stories about young characters for older readers, the ways in which the manga intends to engage its audience can be trickier and more interesting. Such manga might deal with coming of age matters, but also might hope to recapture of the spirit of youth or even delight in regressive thinking.

Part of Wandering Son's hook is a distanced view at discomfort with one's own body. The manga is written to evoke the feeling of being ill at ease in one's own skin, such that everyone who has went through puberty can sympathize with these characters, regardless of their own relationship with sexual identity issues.

I'm not so sure how particularly, generally appealing the prospect of reliving those feeling may be, but that sort of identification is a crucial part of what makes Wandering Son a superlatively fascinating manga. We're not gawking at these characters. We're not marveling at the ingenious convulsions of the relationships between them. And, my voyeurism test isn't applicable either. I've said in the past that a good measure of how interesting a manga drama may be is whether you'd listen in on the conversation if you overheard someone discussing the problems in their own life. That's not really relevant to Wandering Son.

The tone of Wandering Son has been pretty light, but there's a provocative edge to that. The characters are written in a fashion that is genuinely appropriate to their age. So, negative reactions to the protagonists are the product of hurtful, poor impulses on the part of their classmates rather than anything truly hateful. At the same time, while the protagonist take their circumstances fairly seriously, they really aren't over thinking the implications of following their feelings.

Yet, you can't help but think of the difficult path ahead for these characters. Regardless of the tone of the manga and regardless of how familiar or unfamiliar we are with the particulars of gender and sexual identity issues in Japan, we, the reader have a better notion of the difficulty ahead than the characters themselves.

You're sympathizes with the characters, you see the pitfalls ahead, and you're decade(s) older. At the same time, the characters are looking for models to emulate, whether it's thinking back on how to react based on what they read in Anne of Green Gables or considering what they've been told by adult friends.

Viewing what happens in Wandering Son from an adult license is fascinating in the way that a time travel story is fascinating. Looking at the fraught paths taken by these character, we start thinking about our own lives and "if only I'd known then..." "I should've" "I shouldn't haven't." This is far from a fantastic manga, but reading it, one can get sidetracked by the fantasy of leveraging adult experience to employ impersonal jiu jitsu to, in the very least, to get out of some of the more dire circumstances of our adolescent years.

That "if only I'd known then..." appeal is only made more potent by its impossibility. Wandering Son is not some sort of social puzzle. Especially because it's not a plot driven manga, we can only watch the characters. We might have some vague notion of the pitfalls ahead, but because the manga is developing in naturalistically, the story doesn't lend itself to straight forward judgment of the characters' decisions against supposition as to what the right course may be. Shimura Takako finds interesting ways to slap down the notion of mature wisdom as well. It's almost a bit of a running gag that Shuichi's 7th grade, older sister thinks of herself as something of a mature sophisticate, while being pretty much a kid herself, while the judgment of the pair of well meaning adults who befriend the protagonist can certainly be called into question as well.

I question how healthy some of the young character-older audience manga are. Ignoring the whole lolicon conversation for a second; nostalgic wishing for a less complicated, more opening hearted life strikes me like a particularly virulent form of escapism. There's enough arrested development around that it’s worth mistrusting odes to childish though.

In contrast to manga that inspires wishes for idealized simplicity, reading Wandering Son, you can't help think of the difficulties ahead in its young character's lives. What's more interesting about the exercise is that, as readers who are older than the characters, we think our advanced wisdom should put us ahead in figuring out the best course, but with all the complexities involved, we can largely only follow along. Though it may or may not be an effective mirror to our own lives, it has its reader thinking about everything, both small and significant, shape us. As a result, Wandering Son proves to be deeply involving in an unconventional way.