Merrick here...

SHERLOCK HOLMES seems to be in vogue these days. The past few years have brought us several inventive adaptations of Arthur Conan Doyle's source material, and there's more on the way.

The already released Robert Downey Jr. variant (SHERLOCK HOLMES and SHERLOCK HOLMES: A GAME OF SHADOWS) will apparently spawn another installment soon (details HERE). A brilliant modernization of the concept called SHERLOCK, from DOCTOR WHO's Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, recently completed its second Season / Series in U.K. - those eps will air in the U.S. in May on PBS. More of that incredible show is on the way, later this year perhaps? Early next? CBS recently commissioned their own modernization of Sherlock Holmes - although that one may hit turbulence (details HERE).

There's even this bizarro version of the conceit coming from Hungary!

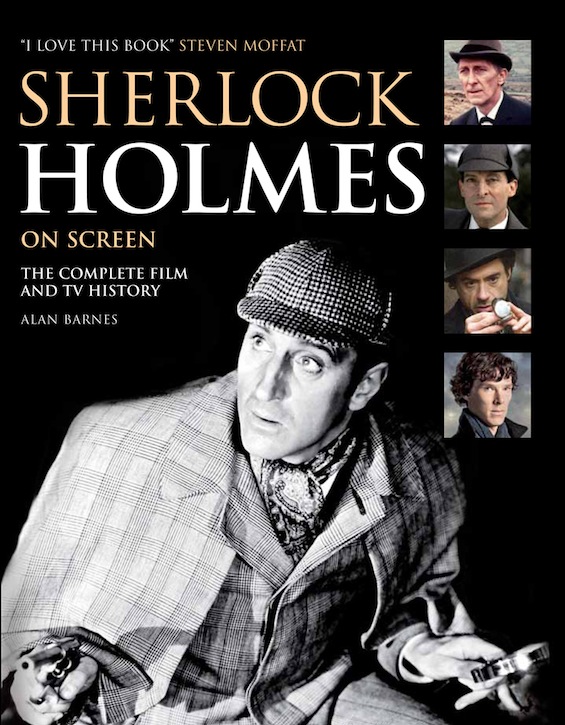

All of this is just the tip of the iceberg - and refers only to contemporary SHERLOCK HOLMES interpretations. The long history of previous adaptations is far more elaborate than many might sense at face value - so much so that author Alan Barnes set out to research and catalogue the history of the character on big screen and small. The result is SHERLOCK HOLMES ON SCREEN, from Titan Books.

Featuring a Foreword by Steven Moffat, the book comes in at 320 illustrated pages. Barnes' work appears to be rather thorough, touching on HOLMES TV and movies both memorable and obscure. The character's 1992 appearance on the NINJA TURTLES animated series is reflected herein, as is 199's SHERLOCK HOLMES IN THE 22nd CENTURY television project.

Included in the book is, appropriately enough, is Barry Levinson's YOUNG SHERLOCK HOLMES (1985) - a film I never enjoyed very much myself, although its opening title theme is pretty great.

Titan was kind enough to send along the below excerpt from SHERLOCK HOLMES ON SCREEN, which gives you a nice sense of the kind of information you'll find in the publication. The book (this is it's third updating) releases on January 31, and is pre-orderable HERE!

A heartfelt thanks to Titan for providing this excerpt for our audience - ENJOY!

-----------------------------------

Young Sherlock Holmes

aka Young Sherlock Holmes and the Pyramid of Fear [GB]

The Mystery

A cloaked figure carrying a blowpipe stalks an accountant named Bentley Bobster – and manages to shoot a dart into his neck unnoticed. As he sits down to eat, Bobster suffers an hallucination in which his poultry course comes to life on his plate. Back home, Bobster’s bedroom fittings appear to become fire-breathing serpents; convinced the room is ablaze, Bobster leaps to his death from the window. Soon after, the Reverend Nesbitt falls victim to the same assassin; believing a knight in a stained glass church window has come to life, Nesbitt flees into the road and is run over by a carriage. Meanwhile, young John Watson is sent to a boarding school, Brompton, where he is billeted in a dormitory alongside an older student, Sherlock Holmes – the brilliant protégé of schoolmaster Rathe.

Holmes is in love with Elizabeth Hardy, the niece of Rupert T Waxflatter, a retired teacher- turned-inventor who lives on the school premises. Holmes notices that Waxflatter has kept cuttings relating to the deaths of both Bobster and Nesbitt; suspecting a connection between the two, Holmes consults Detective-Sergeant Lestrade, who dismisses his theory. Back at Brompton, Holmes’ rival, Dudley Babcock, conspires to have Holmes expelled for cheating in an exam. But as Holmes exits the school gates, Waxflatter himself proves to be the killer’s next victim – and accidentally stabs himself to death while attempting to beat off an illusory bronze harpy in a curio shop. Waxflatter’s dying words to Holmes are entirely cryptic: ‘Ehtar, Holmes, Ehtar.’

The Investigation

Holmes trails a mysterious stranger seen at Waxflatter’s funeral, but loses the track. Holmes holes up in Waxflatter’s rooms; Watson reluctantly agrees to help Holmes and Elizabeth find the killer. Holmes and Watson return an Egyptian blowpipe dropped at the murder scene to the curio shop; the shopkeeper trades them the address of the man who bought the blowpipe from him some time previously. At a seedy Egyptian tavern, the pair are confronted by hostile devotees of Osiris, the Egyptian god of the dead. Beating a retreat, they analyse a piece of cloth torn from the killer’s cowl by Elizabeth’s dog. This leads all three to a paraffin factory in Wapping, inside which they discover a giant pyramid built by Egyptian cultists. Holmes attempts to prevent the cultists’ masked high priest from mummifying a still-living girl; the attempt is unsuccessful, and all three are struck by the nightmare-inducing darts in their flight, only just escaping with their lives.

A picture showing Waxflatter and the two other victims as young men leads them to identify the next target: Chester Cragwitch, the man seen at the funeral. Cragwitch tells Holmes and Watson that in Egypt, many years previously, the four had discovered an underground pyramid containing the tombs of five Egyptian princesses; they stirred up local unrest, leading to the massacre of many local villagers by the British Army. ‘Ehtar’ was a surviving Anglo-Egyptian boy who, together with his sister, swore vengeance on the four. Too late, Holmes realises that ‘Ehtar’ backwards spells ‘Rathe’. They rush back to the school – but Rathe and his secret sister, school matron Mrs Dribb (actually the assassin), have already kidnapped Elizabeth, who is to be the fifth English girl murdered by the cultists in their bid to avenge the five ancient princesses…

The Solution

Holmes and Watson pilot Waxflatter’s ‘flying machine’ to Wapping, crashing into the frozen Thames close by. Holmes then contrives to bring the cultists’ own pyramid down on them before Elizabeth can be sacrificed. Mrs Dribb is killed, but Holmes is left for dead in the burning pyramid; Watson simultaneously rescues Holmes and prevents Rathe from escaping with Elizabeth. Elizabeth is mortally wounded when she steps in front of a bullet Rathe fires at Holmes; Rathe and Holmes duel on the frozen river, where Rathe meets his apparent end, sinking into the icy depths. Elizabeth dies. Heartbroken, Holmes gathers up the things he has collected during the adventure – a deerstalker, a pipe and Rathe’s coat – and makes his lonely way out of the school. In Switzerland, a man signs into an Alpine hotel under the name ‘Moriarty’: it is Rathe.

***

It comes as some surprise that Young Sherlock Holmes, a picture produced under the executive eye of Steven Spielberg – the director who, in the seventies and eighties, rewrote the Hollywood record books with the enormously successful Jaws, Close Encounters of the Third Kind and ET (the latter referenced in Young Sherlock Holmes, when Waxflatter’s flying machine crosses the moon) – should prove quite so downbeat. Cravenly book- ended by two verbose on-screen disclaimers (‘Although Sir Arthur Conan Doyle did not write about the very youthful years of Sherlock Holmes and did establish the initial meeting between Holmes and Dr Watson as adults, this affectionate speculation about what might have happened has been made with respectful admiration and in tribute to the author and his enduring works’ – oh, please), heresy is the least of the crimes of which the film might be accused. Its single Academy Award nomination might make it a rarity in Sherlockian cinema; that that nomination should be for visual effects trickery tells a tale in itself.

Young Sherlock Holmes was made by Amblin Entertainment, a company founded by Spielberg, Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall. Amblin’s previous productions had included the grotesque comedy Gremlins (1984) and a dismal children’s treasure-hunt adventure, The Goonies (1985) – both of which were scripted by Young Sherlock Holmes’ screenwriter Chris Columbus, who would later become the director responsible for the unfathomably popular family-friendly films Home Alone (1990) and Mrs Doubtfire (1993). Young Sherlock Holmes avoids a similar insipidity, but then it enjoys a director of a different calibre altogether: Baltimore-born former stand-up comic Barry Levinson, whose prior works had included nostalgic coming-of-age movie Diner (1982) and baseball drama The Natural (1984). Levinson was joined by Mark Johnson, producer of both of the latter, on the Holmes picture, which was filmed in the UK in the summer of 1985 at the Thorn EMI Elstree Studios, Borehamwood, Hertfordshire, with other locations including Wapping, East London and Radcliffe Square, Oxford.

Its three young principals were all virtual unknowns: as Holmes, MP’s son Nicholas Rowe (born 1966), an Old Etonian who’d appeared in Another Country (1984), Merchant-Ivory’s drama of homosexual stirrings in an English public school; as Watson, Alan Cox, the 14-year-old son of actor Brian; as Elizabeth, Sophie Ward (born 1966), daughter of actor Simon and with minor roles in The Hunger (1983) and Return to Oz (1985) to her credit.

Groundbreaking computer-assisted effects work by Industrial Light & Magic, a facility set up in the wake of Star Wars (1977), gave life to the ‘Glass Man’, the stained-glass knight which menaces the Reverend Nesbitt, but other techniques employed were rather more traditional. ‘Go-motion’ animated the gargoyle-like bookends that torment Waxflatter, while rod puppets were used in the scene where the contents of an imaginary pantry come to life to threaten young Watson (the realisation of which took Dr Pretorius’ ‘miniature people’ in 1935’s Bride of Frankenstein for its inspiration).

The many, many ways in which Young Sherlock Holmes contradicts the ‘Sacred Writings’ are glaringly obvious (Holmes and Watson first meeting nearly 20 years prior to their first meeting in A Study in Scarlet, etc) – but leaving Doylean pedantry aside, the fundamental problem with Columbus’ story is that it bears precious little resemblance to a Sherlock Holmes plot. Many commentators have remarked on the similarities between Young Sherlock Holmes and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), the Spielberg- directed prequel to Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) in which Harrison Ford’s adventurer-archaeologist uncovers a homicidal band of Thuggees at work in 1930s India. Although it’s entirely true to say that the ‘pyramid’ sequences in Young Sherlock Holmes – in which our heroes (adventurer, his love interest and his short, round sidekick) observe a foreign cult’s high priest practicing ritual sacrifice in a vast, hidden temple – are near shot-for-shot identical to the Temple of Doom scenes in which our heroes (adventurer, his love interest and his sidekick, Short Round) observe a foreign cult’s high priest practicing ritual sacrifice in a vast, hidden temple, it’s a little disingenuous to suggest, as some have, that one is simply a more child-friendly remake of the other – certainly when one considers alternative sources for Young Sherlock Holmes…

The blowpipe-wielding assassin might be said to derive from Tonga in The Sign of the Four, were it not for the fact that such a character would be equally at home in the Fu Manchu stories of Sax Rohmer, in which a foreign malefactor establishes himself as a kingpin among the immigrant workforce of a fogbound olde London; in which exotic poisons, such as ‘the Zayat Kiss’, cause mysterious deaths in locked rooms; in which the villain builds himself a base of operations among the creaking wharves of the eastern Thames; in which hordes of obsessive devotees of the villain menace the dogged detective on the trail of their overlord, his eternal, seemingly indestructible, adversary… (Although Rohmer is most known for his stories and novels featuring the Chinese ‘devil doctor’ Fu Manchu, beginning with 1913’s The Mysterious Dr Fu-Manchu, it should also be noted that many other of his works, such as 1914’s The Romance of Sorcery, display evidence of the writer’s life-long obsession with quasi-Egyptological mysticism – another key facet of Young Sherlock Holmes.) Put bluntly, Columbus’ screenplay is an elegant and reasonably expert pastiche of another series of early 20th century British thrillers entirely – a series so removed in concept, style, intended effect and intellectual weight as to be anathema to Doyle’s Holmes.

No wonder, then, that Young Sherlock Holmes is held in such generally low regard by aficionados, despite its many virtues: Holmes’ youthful insouciance (he believes that three days ought to be long enough to master the violin); a tour de force sequence in which Holmes is challenged to recover a stolen fencing trophy; Holmes’ baiting of a patronising, piggy-faced Detective-Sergeant Lestrade; an utterly charming little scene in which Watson is finally persuaded to assist the expelled Holmes, so breaking school rules (Watson: ‘I can’t afford to jeopardise my medical career.’ Holmes: ‘Weasel.’ Watson, huffy: ‘I’m not a weasel. I’m just – practical.’ Holmes, cutting: ‘Weasels are practical…’); and, strikingly, Holmes’ hallucination, in which he imagines a bizarre domestic tableau where he fails an austere and aloof father. Altogether less successful are the film’s efforts to describe the making of the man: Holmes’ desire never to be alone is dashed by the strangely distant death of the strangely remote Elizabeth – an aspect doubtless distressing for a young audience, but quite in tune with the film’s rather cruel, near- sadistic edge. Note also the killing of cuddly father figure Waxflatter, beautifully played by Nigel Stock – Watson in the two sixties BBC TV series Sherlock Holmes and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock

Holmes– which is as one with the film’s many gleeful, comic-horrific, special effects slayings.

Famously failing to make any real impact at the box-office (reportedly, it grossed just $4.25 million in the USA), Young Sherlock Holmes may have flopped in its day – but ought now to be feted as a dress rehearsal for something in an altogether different league. The terrifyingly profitable Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (2001), based on the literary exploits of the most noted fictional character of the age, sees a precocious clever-clogs, his sort-of girlfriend and his weaselly sidekick uncover nefarious goings-on at an English public school, all orchestrated by a wicked schoolmaster devoted to devilish ways. Spearheading an ongoing franchise, Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone was, of course, directed by Chris Columbus.

Copyright © 2002, 2004, 2011 Alan Barnes. All rights reserved.

-----------------------------------

--- follow Merrick on Twitter ! ---