Nordling here.

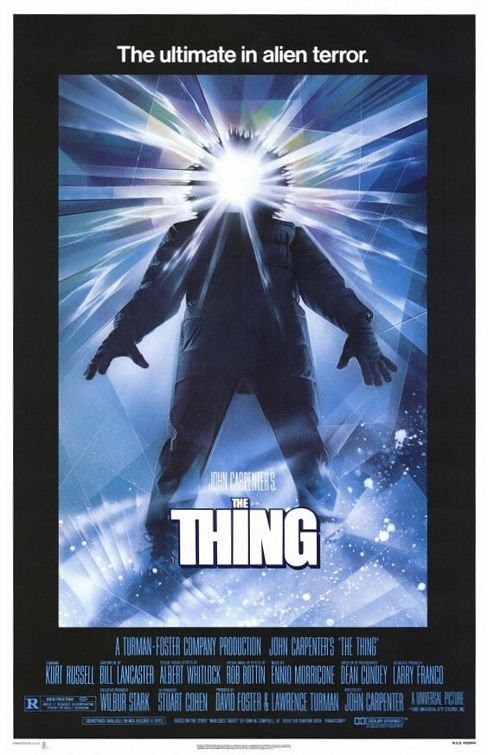

I’m not sure how many people remember those halcyon days of 1982, but when it was reported to genre movie fans that John Carpenter was going to remake THE THING FROM ANOTHER WORLD, at the time, the reaction was more akin to anger than anything. Christian Nyby’s film – although it’s been stated that Howard Hawks actually directed it - was (and still is, in a lot of respects) something of a sacred cow. Now the guy who made HALLOWEEN and ESCAPE FROM NEW YORK was going to tackle it. I was young at the time, but I remember a lot of critics gathering their armies against John Carpenter for having dared remake a classic movie like that.

John Carpenter’s THE THING is definitely a movie that didn’t get its respect until much later, because in 1982 it was only a middling success at the box office. Remember, 1982 was the summer of E.T., and no one wanted to see this dark movie about paranoia and distrust, filled with for the time was spectacular gore effects and disturbing imagery. But now, we know THE THING as an utter masterpiece of tension and horror, and it’s a movie that deserves analysis and respect. What Carpenter did was make a film about how the distance between people can be far greater than the interstellar distances that the Thing travels to get to our world, and how people are unwilling or unable to bridge the gulf. It’s a hugely pessimistic movie, but it also relies on how much each audience member personally brings to it. It’s widely open to interpretation and feels tailor-made for each particular viewer’s sensibilities. That’s extremely hard for any movie to do, especially a genre film, and I still don’t think Carpenter is given the respect that he’s due because of it. THE THING is, in its way, even more terrifying in what it has to say about human relationships than in any gore effects, and the gore effects are amazing, and still have yet to be topped today.

That was what was so offensive about the recent remake/prequel: like so many filmmakers just focusing on the “cool” aspects of the original movie, they forgot that THE THING works as well as it does because of the characters and their relationships. There’s a lot of unspoken dialogue in THE THING, and what I mean by that is that the film relies much on what the audience does in their mind to fill the spaces. THE THING doesn’t beat you over the head; it’s not obvious, and it lets the audience play with the film’s dynamic in their head. We always speculate about the nature of the alien, about who could be next, and because the movie wisely never quite lets you in in regards to the characters, we always wonder about each character’s motivations. Even the end has ambiguity and isn’t an easy resolution. THE THING gives you a lot to think about, and it’s a testament to the film’s greatness that this can be debated all these years later.

Carpenter wisely decided not to remake Nyby’s film, but instead directly adapted the novella that the original film was based on, “Who Goes There?” by John W. Campbell Jr. That story has many of the characters that we’ve come to love in Carpenter’s version, and the story is full of the paranoia and darkness that show up in the film. The ending of the story is fairly typical for science fiction pulp stories of the time, but Carpenter wanted to explore those relationships more in the movie. I love how we know next to nothing of the characters’ back-story, but I’ll get to that in a bit. For the purposes of this article, I won’t be writing too much about the original novella, and instead focus on the characters as they are presented in the movie. The movie stands on its own as a complete work and I don’t think it’s even necessary to go back to the source material to understand what makes THE THING as good as it is.

I realize that I may be thinking about this movie, and the ideas that it delivers, more than might be normal. But THE THING is like that – it gives viewers who are willing to pay attention a lot to chew on, and it’s always been one of those movies that I play in my head. I’ve probably seen it over 30 times – not the record, I’m sure, but enough to be pretty familiar with it. And although I’m sure many fans realize it, but the secret weapon of John Carpenter’s THE THING isn’t his direction, which is admittedly great, or the terrific acting, or Rob Bottin and his team’s fantastic make-up effects work. No, it’s the work of one Bill Lancaster, the screenwriter. Sadly, he’s gone now; Lancaster died in 1997 with not very many screen credits to his name, but two in particular stand out – THE THING and the original BAD NEWS BEARS. They are fantastic scripts, with real characters that live and breathe. THE BAD NEWS BEARS is one of the best films to genuinely portray childhood with all its bumps and bruises, and with that script Lancaster knew that childhood, like anything else, wasn’t easy. Lancaster’s characters in THE THING feel the same way.

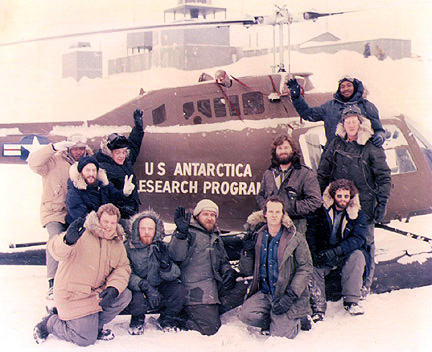

We know next to nothing about MacReady, or Garry, or Childs, or Clark, or Palmer… and the film works because of that. So many films nowadays need to tell the backstory of every character so as to easily explain every single motivation. THE THING dispenses with all that, and it makes for a much stronger movie. One thing is certain – these men, working at the ass-end of the planet, are already distrustful of people. You don’t work at an Antarctic research facility unless you’re at the beginning of your career or at the end of it, or you’ve pissed off someone sufficiently that it was the only thing you can get. I’ve thought about this a lot, and I’m not sure if this is something that other fans of the film have done, but I’ve come up with pretty extensive backstories for those characters in my head, and the movie wisely lets the audience think for themselves about who these people are and how they came to be in this place and this situation.

Let’s take MacReady, for example. Kurt Russell is very effective as the helicopter pilot who, when not hauling gear and personnel all over Antarctica, drinks himself into a stupor every night and spends time alone. You get the idea that MacReady doesn’t like people. Even in his very first scene, Russell lays out the character for us in broad strokes – playing chess on a gaming computer and quietly getting drunk, and when he loses he simply pours his drink into the computer’s hard drive. This sets the tone for what follows – as Mac plays his own game with the Thing throughout the film, he’s completely willing to rip everything down to its foundations to “win.” “Cheating bitch,” says MacReady, and blows up the whole damn thing. That’s MacReady to a T – if he can’t beat the Thing, he sure as hell won’t let it win on its own terms either. I always imagined Mac as a helicopter pilot in the military who saw some pretty heinous stuff, perhaps in Vietnam or Cambodia, and working in Antarctica was the furthest place he could get away from people without leaving the planet entirely. He’s the ultimate reluctant hero, and if he can’t be a part of the world he sure as hell won’t let some Thing take it over either.

That’s the greatness of Lancaster’s script, and it’s difficult for most screenwriters to pull off; creating characters without so much exposition is a tough gig, but Lancaster does it perfectly. Even more, the script lets the actors play around with it, and bring their own sensibilities to their roles. You get someone like Fuchs, who is a character without much dialogue, and Joel Polis plays him as an eager scientist, probably at the beginning of his career, and although it’s not there in the dialogue it’s very evident in the character. Or Childs (Keith David), who distrusts all authority, unless it’s his own. I always had the idea that working in Antarctica was probably the last job Childs could get – he’d pissed off too many people over the years and the only thing left was working in the cold with these stupid white people.

Blair (Wilford Brimley) is one of the most interesting characters of the movie – at first, he’s the most concerned about the Thing and the potential it has to infect the planet, but once he goes ballistic on the rest of the team, he can’t be trusted and is placed under house arrest. One of my favorite scenes in the film is when Blair begs Mac to be let back in with the rest of the guys, as a noose hangs in the background. When does the Thing take him over? How does it happen? The movie never answers it. Personally, I always think of the scene when he’s examining the Thing-carcass and touches it with his pencil eraser and then brings the eraser by his mouth. That’s just how my mind works. But what kind of a man is Blair? He’s obviously a scientist, but how did he end up in Antarctica? The crucial scene is when Blair runs the computer program that reveals that if unchecked the Thing could literally take over the planet, and how he reacts. Whatever problems Blair had with others, he simply can’t allow the Thing to leave the station.

Or you get Palmer (David Clennon), who gets the film’s best, most memorable line, and the wonderful thing about that line is when Palmer says, “You’ve got to be fucking kidding,” he’s a Thing! The creature so thoroughly takes over its host that it has access to memories and even personality, so short of MacReady’s blood test there’s no way to tell if they’re human or not. Potentially, it could be anyone – you could be having a conversation with the Thing and not even know it. It’s all done through dialogue and acting, and it’s not spelled out for the audience in a stupid, obvious manner. Less ambitious, not-as-skilled screenwriters or directors would have dotted every i and crossed every t to make sure that they explained everything, and THE THING trusts the audience enough to keep up. One of the many problems with the prequel is that it became obvious quickly who was a Thing, but that’s not how the creature is supposed to work. For the most part, no one has any idea who’s who, and that adds to the tension and paranoia.

This rewards multiple viewings like you wouldn’t believe – THE THING is one of the most rewatchable movies ever made because there’s always something new and interesting that comes up, even if it’s through a minor character interaction or turn of phrase. Maybe it’s just me, but I still don’t know who “got to the blood.” I assume it’s Blair, but at that point in the film he hadn’t turned yet, and even then I’m not sure. When did Norris get infected? When does Blair? The movie never lets us in, and THE THING becomes one of those movies that you get to take home with you once it’s over, because it’s set up so well that you speculate on everything. For some people this could be considered a flaw of the film that it doesn’t spell everything out. Not to me. I think the key to the movie’s success as an artistic work is that we get to play with it in our heads.

I’ve barely mentioned Rob Bottin’s make-up work, and it is truly tremendous, and is probably the best reason why the film practically refuses to date itself. The work of Bottin and his team is simply unparalleled. It’s why the prequel’s use of CGI is looked at with such disdain. The Thing can be anything it wants to be, can change shape in any way possible, and Bottin’s work here is one of the few pre-CGI works that seems effortless in how it shows each transformation. Combined with Carpenter’s direction and the work of Dean Cundey, the result is a movie monster that literally can do or be anything. The practical effects work of the Thing still stuns to this day. Look, I don’t hate CGI – it’s just another tool that can be used effectively and well. But there is simply no substitution (at least, not yet) for real, hands-on make-up work. Watch the documentary THE THING: TERROR TAKES SHAPE and you’ll see just how amazing their work was. The 1980s were definitely the heyday of make-up effects work, and honestly they don’t get much better than THE THING.

Ennio Morricone’s work here has to be mentioned as well – his score is spare but unrelenting, and is yet another score in a long line from the master. Dean Cundey’s cinematography is stark and beautiful, and he’s always been Carpenter’s go-to guy with the camerawork, but THE THING may be his most signature work. And then, there is @TheHorrorMaster himself, John Carpenter. THE THING was his seventh feature-length film, and it’s probably his best film. Carpenter knows how to raise the tension so subtly that by the time you realize it, you’re in the movie’s grip. Carpenter’s horror films of that era weren’t great because of the gore, but because Carpenter used every bit of his considerable power to slowly draw you in, so that when the real scares come they’re genuinely frightening. Carpenter also had a real affinity with the actors, allowing them to find their own character in the spaces between the dialogue. These people felt real, as opposed to simple character tropes. And that’s probably the biggest reason why THE THING has stood the test of time – you genuinely like these people, even when they collide, and it hurts when the shit goes down.

And then there is the ending, which boosts the film into classic territory – MacReady, having dispatched the Blairmonster and set the compound ablaze, sits down in the night storm, resigned to his fate. Suddenly, movement – it’s Childs, who managed to get away from the explosion and is seemingly the only other survivor. Together they sit, as the temperature drops, each full of mistrust and doubt, watching each other closely, knowing they will inevitably freeze to death. People have speculated for years about the final scene – is Childs a Thing? My own theory is this – he’s not. He’s human. And as they slowly freeze, they could figure something out together and try to survive what’s coming, but because of their mistrust and suspicion for each other, they simply can’t cross that bridge. It’s a nihilistic ending and the only one that fits the mood of the film. THE THING is full of people who are crippled by their lack of trust in each other, and as the Thing preys on that mistrust, it’s the humans who bring themselves down more thoroughly than the Thing ever could. These are broken people who for whatever reason can’t relate to others and the moral of the film become a cry for unity and solidarity, even among such disparate personalities as these. The real horror, THE THING suggests, is in our failure to relate to one another. Carpenter’s movie is a certified horror classic and still resonates to this day; films that have tried to capture just what Carpenter did with his movie have failed, including the awful prequel, which has a complete misunderstanding of why Carpenter’s film works so well. THE THING isn’t optimistic about our chances, but in its bleak worldview we come to an understanding – people need each other. A simple enough message, but told amazingly well.