Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Before spotlighting four very AICN appropriate manga, the big news in North American anime industry needs to be mentioned. Bandai Entertainment, the folks that released Cowboy Bebop, Gundam, Escaflowne and the Girl Who Leapt Through Time, will stop releasing new titles on DVD, Blu-ray and Manga formats starting in February of 2012.

The company will continue to sell catalog titles and shift its operation to licensing which will include digital distribution, broadcast and merchandising.

As a result of this change in strategy for the North American Market, Bandai Entertainment’s organization will be restructured at the end of January 2012.

The following previously announced anime titles have been canceled: Turn-A Gundam, Nichijou and Gosick.

There has been a lot of talk of this in terms on piracy, but, as I've said on Twitter, I believe that piracy is the context and not the story of Bandai Entertainment's shutdown. Piracy is chief among the reasons why it is difficult, if not impossible to make money on anime, but beyond that, Bandai had problems with delays, with getting media replicated, with publicity, with corporate encumbrances and barriers. They were built for a time when anime sold itself, and during those boom years, they had some outstanding talent working for them. They weren't built for bad times, and piracy certainly did contribute to the bad times. Ultimately, it was easier for Bandai Namco to shut down the outpost than it was to fix it.

Manga Spotlight: No Longer Human

Volumes 1 and 2 (of 3)

By Usamaru Furuya

Based on the novel by Osamu Dazai

Released by Vertical

No Longer Human deals with one of manga's favorite subjects, alienation. From Naruto to Fruits Basket, to the other three manga in this column, manga has found fertile ground in the subject of people who feel separated from the rest of the world. No Longer Human" adapts the granddaddy of Japanese alienation stories; literary giant and "Poet of Despair" Osamu Dazai's monumental 1948 novel, one of post War World II Japan's historical best sellers. As such, the distinction here is that this manga has heavy literary heft, or maybe baggage, behind it. "

In three first person memorandums that map out key points in a life that is something of a psychological Superfund site, "No Longer Human" tells the story of Yozo Oba. This is a guy who seems like he should be an object of envy, coming from a wealthy family, possessing talent, possessing good looks, possessing defense mechanisms that allow him to feel out comfortably popular positions in groups, while being infallibly attractive to the opposite sex. Yet, he's defined by a perpetually collapsing orbit towards self destructive. This doomed life could be poor little rich boy or poor suffering artist, but Dazai balances the indictments to be specific to Oba and universal. There's cause to react to, and disconcertingly identify with the subject. What's generally credited with helping fuel this look into the abyss was that No Longer Human's pitched battle with trauma, identity, and fear of success and failure was hardly foreign to its author.

Shuji Tsushima, born in 1909, was the eighth surviving child of a wealthy landowner. His education was distracted and ultimately ended by dalliances with booze, hookers and Marxism. He was expelled from the family for running away with a geisha, after he which survived a joint suicide that took the life of a bar hostess. During the 30's he managed to develop a literary career under the pen name Osamu Dazai, known for his first person style; he battled morphine addiction, attempted suicide by himself and with his first wife. He managed to remain published in the 40's despite war time censorship, and continued to write after the conflict's conclusion, adapting his subjects to speak to the changing constraints and times. His alcoholism got worse, as he fathered a child by a fan he slept with, abandoned his second wife, and, while serializing a novel about a self destructive man whose biography mirrored his own, he succeeded in a joint suicide with the war widow he'd been living with.

There was a tabloid quality to how No Longer Human's subject's life closely mirrored Dazai's, but it was also the zenith of a literary great's opus. It's the timeless regard rather than the sensationalism that's been the issue for past adaptations. Adaptation of literary novels like No Longer Human is that they can, and in this case often have, worked off the virtue of being important. The bland Manga de Dokuha, Classics Illustrated equivalent that runs on digital manga site JManga has this issue. There's an anime from Gunslinger Girl and Cardcaptor Sakura director Morio Asaka, that was included in the Aoi Bungaku/Blue Literature (along with an adaptation of Dazai's 1940 parable Run Melos!), but while well animated, Aoi Bungaku's aims were to be a reminder of the power of literature, and in the case of No Longer Human, the production erred towards being too straight and trying too hard to do well by the material.

To complete the anime/manga adaptation conversation with the exception that proves the rule, there's also Yasunori Ninose, No Longer Human Destruction, which involves tentacles and like most things in its home anthology, Champion Red, it's a bit fucked up.

Created in honor of Osamu Dazai's 100 birthday, Usamaru Furuya's No Longer Human works from something of a gimmick to move the story to the current era. The analogues fit amazing you well, and succeeds in diffusing the over importance while also asserting its timelessness. You wouldn't necessarily guess that this is a modernized pre-World War II story if you didn't know, and if you did know the vintage, but not the story's specifics, you'd be surprised by the details that are close to the original, whether it's Oba's relationship with bar hostesses, his relationship with a single mother, his career as a (manga) artist, or his dalliance with a protest movement. It anything goes down easy in this disconcerting story, it's the timeframe update.

In the original novel, an anonymous person finds Oba's memorandums. A fundamental change here is that the manga opens with a framing sequence in which a manga artist identified as Usamaru Furuya is finishing off his latest work, and frustatedly searches for a premise for his next serial. An anonymous message post directs him an "an ouch diary" blog, introduced with photos of a smiling 6 year old, a handsome, affectedly grinning 17 year old, and prematurely worn out 25 year old. Furuya wonders what could have happened between the three photos and becomes enthralled by the blog/web memorandums.

Furuya distances the reader from his self portrait by giving the manga surrogate eye glasses that are always reflecting the light of the computer screen such that we never see his eyes. In Japanese, the phrasing for "ouch blog" uses "ouch" in the sense of an eyesore, the same sort of way that one of those cars with an embarrassing anime character decorated on the side is referred to as a "ouch" or hurt car. And, despite the eyeless impersonalness, as Furuya reads about how teen Oza was perpetually friendly and conscious never to over-succeed in order to maintain his carefully cultivated likability, the author's distaste is evident from his monitor illuminated expression.

Oba's story fits firmly into Furuya's wheelhouse. It's not as darkly playful as his other works released in North America, such as the bleakly funny gag Short Cuts or the Secret Comics Japan sampled Palepoli, shonen art/psychological interpretation Genkaku Picasso or Grand Guignol Lychee Light Club, factor in his other dark, less than reverent views on humanity seen in the viral death urge of Suicide Circle, apocalyptic earthquake in 51 Ways to Protect Her or historical Innocents Children’s' Crusade, and the consistency is recognizable. At the same time, its clear that while he can't turn away from the story, he finds it unpleasant. As such, the framing device introduces an element of recursion into the manga. Furuya the character, presumably Furuya the writer, and the anticipated reader are following Oba's story with a mix of voyeurism and masochism.

These frame device places the first mirrors in the manga's funhouse approach to Oba's story. Beyond that, Furuya starts with a visual approach that is straighter than much of his manga, except for when it isn't. Most of the style is recognizably Furuya, but notable for its normality, especially as compared to other of the artist's works. However, in key moments, Furuya refracts this. There are scenes in which Oba in his capacity as a artist himself drops all self-censorship and produces images that merge with the peaks of Furuya's grotesque nonsense. Those are the manga's showy extremes.

Furuya uses a shift into charcoal for jumps from an account of life to metaphor, whether it is how Oba is thinking, such as when he considers himself like a puppets or sees a year book of "ordinary" classmates flutter off into ghostly, faceless sheets, and the approach is likewise taken when the reality of story becomes symbolic, such as a the image raised hand with a butterfly tattooed on it. Furuya also swaps out level of stylization. Sex scenes in particular strip off the abstraction and indifference to the how the specifics how people look. When people are naked in No Longer Human, they're naked. You get the folds of skin, and age lines. Heavy people look heavy, old people look old and skeletal people look skeletal.

Personally, I'm not convinced that there is currently an extensive interest in spelunking the depths of humanity. I think back to how controversial Natural Born Killers was versus how many critics this year regarded We Need to Talk About Kevin like a trip to the dentist. Media in this territory has gone from a shock to a bother. Furuya embraces that "ick, I don't want to deal with this" reaction to the

material, and uses to construct an adaptation that is both irreverent and true to the material. In that, he produces a work that he prompts a second consideration in a way that is more effective that earnestly playing up the virtue of being worthy exposure to a classic of Japanese literature.

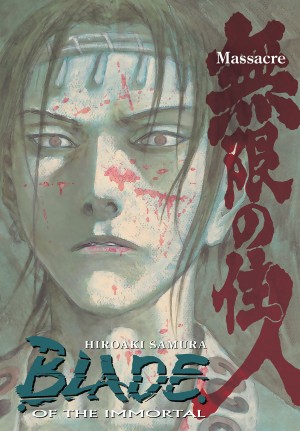

Manga Spotlight: Blade of the Immortal

Volume 24: Massacre

By Hiroaki Samura

Released by Dark Horse

Manji, the immortal ronin of the title, is physically present for maybe a dozen pages of this volume, and of that, he's off panel for about a third. Yet, I think fans of this manga, one of the longest running in North America, probably couldn't be happier with the volume. In fact, in you once followed Blade of the Immortal, but stopped, pick up this one. There will be many new faces, but the action speaks for itself and with the interesting way in which it re-approaches the series original moral proposition, the brutal samurai manga is as fascinating as ever. This entry will reward readers who have stuck with the series while giving lapsed ones reason for a second look.

The main thrust of this volume is four members of the renegade Itto-ryu swords school attacking Edo Castle, the military capital of the Tokugawa shogunate. There's Kagehisa Anotsu, the school's cold iconoclastic leader, the closest thing Blade of the Immortal has to an archvillain. Taito Magatsu , Anotsu's far more sympathetic punk revolutionary second. Ozuhan, a deaf wildman, wearing a mask and kilt, who attacks while playing a distracting flute, who has been around in Blade of the Immortal for a while, but more as a demonstration of the truly unconventional warrior attracted to Itto-ryu's revolutionary principles; and Sukezane Baro, a relative newcomer to the series, who acts as the faction espionage agent; a furious fighter who works with a long swords lightened with disks punch out of its blade.

Though the move against Edo Castle incorporates specialists in distraction and espionage, the attack is not Mission Impossible. It's more along the lines of walking up on the generalissimo’s palace, ringing the door bell, then dropping trou to piss on the front step.

With the scale of the castle being attacked, the size of its forces, and the duel page spreads illustrating this, Samura establishes this as a real battle that recasts the series' previous engagements as brawls and skirmishes. In terms of Samura's presentation, it's not one of his early death, symbolism laden murals and not the lethal dances he illustrated in some of the one on one matches in the contest of swords schools. Here, the emphasis is onrushing lethal force. It's violence: real, but not so real that its disquieting, and definitely a spectacle to excite. In a series full of some of manga's most impressive sword fights, it's a best of the best.

The fight is complicated and sustained. There are four attacking warriors, each with an intricate, previously established style: Anotsu with the devastating circles of his swinging axe, Magatsu with his jabbing thrusting and occasional hidden blades, Ozuhan with his ambushes and Baro with his dashes and devastating reach. There's attention to the dimensions of the castle, its layout and the logic of breaking into and movement through it as the group barrels down court yards and around incoming arrows.

Samura probably isn't pretending that any fraction of this is possible, but he still works to make it as real or at least credible as possible. The author's intent to de-mythologize runs a bit into overly noticeable strong here, as in the series' notorious "Prison Arc," where he presents "Decapitator" Asaemon as a wheezy little troll. Here, he pisses on the "hero principle", that a colorful named guy is going put up a better fight than anonymous warrior. Again, he pulls from chambara legends, such as Kumokiri Nizaemon (Samurai Versus Bandits). More often, the reality and spectacle complement each other. Illuminated by the light of a full moon, this heated battle to control the castle grounds is awesomely cinematic. At the same time, especially notable for how well it’s conveyed in manga, there's the physicality of moving through the castle, and there's also the work to remind that these warriors are human. Fatigue has a role in the battle, with blood spattered attackers take cover, eat and drink between engagements. As does the psychological dimension, with Anotsu and his group playing to the shock and awe effect of their blitz.

Beyond the spectacle, what's interesting here is that Anotsu and his Itto-ryu are protagonists of this volume. The perspective is putting the spot light on them. They're the ones attacking. Its the nature of reading that the we're often drawn the people receiving the attention. It doesn't hurt that the overwhelming odds of four against a castle full of samurai is a downright heroic deed. Yet, even if it is heroic, this isn't Dragon Ball where old villains graduate into good guys.

Implicitly, the events of this volume stand in stark contrast to Blade of the Immortal's original moral proposition. The manga's titular hero, Manji, is known as, and referring to again as in this volume, the "100 Killer" for killing the 100 men who tried to bring him to justice after he turned on and killed his brutal, corrupt lord. For that, he was cursed with immortality and swore to kill 1,000 evil men in recompense. The manga never really cosigned on the metaphysical correctness of his idea of killing 1000 "evil" for 100 "good" souls, but it was the original premise for the series.

Here, the Itto-ryu are killing who knows how many, not out of kill or be kill necessarily, brought upon by a debatably ethical act. Magatsu, unlike many of the warriors of the manga, wasn't born into the samurai class, suffered the injustice of the ruling elite, and has more egalitarian beliefs behind his revolutionary action. The rest of the Itto-ryu believe in believe, and, here, act on in a brutal system of proving out who's best. As exciting as the attack on Edo Castle is, it can't help but be seen in terms of troubling terrorism.

There are entirely reprehensible people in Blade of the Immortal. There's one in this volume, and he is involved in one the tableaus of graphic, brutally aestheticized violence against women that disconcertingly fascinates Samura. No matter how belligerent, quick to kill, or morally compromised other characters are, there's that reminder of the sadistic bastards at the far end of the spectrum. The Itto-ryu are hardly white hats, and the reengage swords school was the manga series' original object of vengeance, and Manji's "evil men," but they're now somewhere in the middle of the the manga's muddy, monochromatic spectrum of morality that runs from black to gray. Factor in the brutal lone wolves, the Itto-ryu, the suicide squad gone renegade after chasing the Itto-ryu, remnants of another suicide squad, a team of ninja girls, newly favored government operations chief, and his retainers, and Blade of the Immortal has gotten into some real enemy of my enemy of my enemy of my enemy business, in which even the notion of relative good guy has been confused beyond recognition. The manga started with the moral arithmetic of Manji's 100 good and 1000 evil men, and with all the added variables and perspectives, turned it into a moral calculus.

Most combatants have enough redeeming qualities and Samurai imbues them with enough bad-ass ability that the readers have the opportunity to cheer all but the worst of the worst. Still, many, or perhaps most, of these characters don't even think of themselves as in the right in their own minds. Morally, it's not all a wash. As characters wrestle with their allegiances and obligations or weight their missions against their senses of justice, Samura carves out cause for consideration, rather than allow the reader to passively watch the Battle Royale play out.

In terms of being a provocative, alternative take on samurai revenge questing, Blade of the Immortal has been consistently top notch. However, there was a long phase in which it alienated many readers by explicitly containing itself, and offering action with literally one hand tied behind its back. Now, it has circled back to the original appeal with a fresh take on the premise and action that'll remind fans why this has been a top older audience manga for a decade and a half.

Manga Spotlight: Tenjo Tenge

Volumes 2 and 3

By Oh!great

Released by Viz Media

I'm certainly doing my part. I want to like fight manga that is brutally fun, but otherwise indefensible.

This manga at least looks the part of a great, bad fight series.. It's not quite fair to call Tenjo Tenge a martial arts fight manga from a porn artist, but while Ogure "Oh!great" Ito has gone on to create hit seinen manga, and win awards for his shounen, for better or worse, the porn artist description isn't entirely inaccurate either. Oh!great's razzle dazzle design offers a cast of uber-teens, flamboyantly dressed, with tons of flesh and muscles, eye grabbing in a way that is perpetually one step away from being way over done. A glance at Tenjo Tenge suggests that it should be grade A, riotous, irredeemable fight manga from Ultra Jump, the anthology that Shonen Jump readers who are older but little wiser, are supposed to graduate into. Ultimately, what Mr Great puts out looks great, sexy and muscular, but also makes the creator look overmatched in terms of authoring fight manga.

Comics/manga are fundamentally build around abstracting forms. Draw a shape that suggests a person and the mind will fill in the details. With the level of abstraction there's a balance that varies situationally. You don't want Peanuts to look too realistic, and conversely you don't want something trying to be sexy to look like Peanuts.

This manga gets points for pushing the line of being exaggerated while going less abstracted. Oh!great is a member, perhaps key influencer, in a style of seinen artists who try to suggest a sort of outrageous semi-reality with their work. Hiroya Oku's Gantz is somewhere along those lines, but, unavailable in North America, the works of Boichi (Sun Ken Rock) and Yuuki Yugo (Wolf Guy) are closer.

Oh!great doesn't go easy on himself with the design and then doesn't use faint suggestions. He goes ridiculous and then keeps himself to it illustrating it in detail. He fine tunes his illustrations of shapely knuckle dusters, including all the over the top flair he's added. For example, the lead heroine has long flowing hair, with a cowlick that comes out like a pair of insect antennae. It'd be far easier to give her bug like protrusions with a few lines, but he always makes the incredible super-bangs look like follicled hair.

While what he does isn't naturalistic or tasteful, he does have a sharp grasp on anatomy and fashion, and the effort he puts into applying to every image is apparent. Flip through Tenjo Tenge, and it all looks stunning.

The result is Tenjo Tenge's best feature: at a glance, the impression that you're seeing hormonally, emotionally charged young people looking to throw down. And, Oh!great is great at building up that promise. In the writing, he sells how ferocious his characters are before they even appear on page. In the art, he shows their explosive, wall cracking power. He takes this a step further with great sequences, such as one in which an antagonist goes all Karate Bull Fighter.

In practice, it isn't so much a disappointment as it is an exercise in being trained not to get hopes up too high or care too much about the upcoming.

Fight manga needs to present the fighters, offer a case for why you should care about the outcome of the battle dramatically, why you should anticipate the battle, and then deliver. Or, it can be unpredictable, working off faith established that the unknown will yield something dramatically and spectacularly rewarding. Oh!great's aims are skewed along those lines. He builds up the reputations or potential of his fighters, but it goes wrong from there.

Laziness and lack of ambition are never among TenTen's faults. It tries to build the "I'll be the strongest" contest into a teen epic. There are diverse gradations of that drive to be seen as the best, complex webs of relations, affairs between the students, friendships, enmities and rivalries, shifting allegiances and factions, family lineages, and on and on.

The plot similarly goes big. After the resolution of the manga's first big battle, TenTen goes on this volumes long discursive flashback to when the senior characters were freshmen to examine history between the heads of the two main faction.

Dissecting the fights, it's fine. There will be two pages of characters facing off before one throws a kick. There's then page of the recipient standing unphased. The original attacker follows with a ferocious blitz of blows. And again, we see the recipient, displaying his bad-ass unaffectedness. It's not the most rapid, staccato approach to depicting a fights, but as carefully illustrated as it is, it should be better than fine. And yet, it's amazing how the fights can be bloody and kinetic, and still lugubrious.

In the first collection, I thought the problem was that I had read the material a couple of times, but these volumes were less over-familiar to me. Usually when I'm a bit bored by fight manga, it's because of overly simple choreography, and that's not the case here either.

At issue, while images of TenTen look outstanding and while some of its ideas have similar impact, in long form, it's not really satisfying dramatically or as spectacle.

The manga's troubles are rarely simple or conventional. TenTen does have some problems with offensiveness, such as a wrongheaded approach to the use of rape as another of its showy spectacles. It's a bad page from the seinen play book to use sexual assault for titillation, but Ten Ten always tries to do more, and get less. The rape isn't consequential in a human, credible way. Instead, it is brushed off, until it’s thrown in a character's face as a prompt for the series' volume's long flashback.

There's also the tremendous amount of undressing or screwing that occurs while characters talk through the plot. Similarly, bad taste, but also counterproductive. The problem here is less that the manga is condescending and pandering, and more that it can't get out of its own way. You want the characters to shut up and/or put some clothes on. It needs to talk through the plot or be titillating. Doing both at the same time does neither a favor. It's as if neither the sex nor the drama being discussed is worth the full attention of the characters or the reader.

Single images are the scope at which TenTen is effective. A tendency to diffuse attention applies to the larger manga. Scenes have that problem of undercutting themselves by doing multiple things out once or banking the consequences.

You can squint and see what Oh!great is trying to do with the back-story and the direction, but in practice, the running series is rarely punctuated by an effective point. What those naked conversations accomplish is to lay out a feedback loop of relationships and history. Story arcs in TenTen are not proper arcs. They're tracing routes along that circuit. As such, rather than really move the story, what consequence amount to in TenTen is to send the story along some other convoluted path. The critical example of this and its effect is the move to a flashback arc. The first battle ends. Edicts are issued as a result. A guiding character dismisses the importance of those consequences. And then we are on to some long look at the history of the characters without anything establishing the meaningfulness of the battle. Oh!great deserves credit for his ambition, but he doesn't have what it takes to abandon the tried ascending arcs convention for structuring effecting genre manga.

More problematic for fight manga, these troubles extend themselves to the battles. Big, awesome moments are rarely conclusive to the fights in that the battle don't build up to a "wow!" attack or exchanges that end the melee. By the same token, big awesome fights are rarely conclusive to the conflicts. If the general idea is that these characters are settling things with their fists, they need to settle more, rather than just pound a few more convolutions into the already over complex conflict. The one fight that has really settled something rather than just keeps it primed for the next battle or complicate it has thus far been kept off panel.

Beyond that, TenTen doesn't correlate the reputation to the quality of the action. Some muscled wrestling otaku who clearly isn't going anywhere in the larger scheme of the manga will put on a fairly entertaining outing while one of its world beaters will offer a tiresome round of staring. The unfortunate result is that Tenten doesn't engender much faith in where it's going. There's little reason to care who it matches up because doesn't engender faith that the clash is going to yield something amazing.

Viz is releasing Tenjo Tenge in 2 volume in 1 collections for $17.88, presumably so that the value can offset the fact that the series has previously been released in an edited form by the shuttered CMX. It is a great value, but TenTen seems like it is better suited for small quantities. It's unfortunate that North America really doesn't support anthologies, because that would be the best venue for Oh!Great's TenTen work. Take some of the pressure off developing something ongoing, and feed out a couple of pages of Oh!Great's eye assaulting illustrations a month, and TenTen would be stunning. Offer 450 pages at a go and the compounded faults renders TenTen dull and laborious.

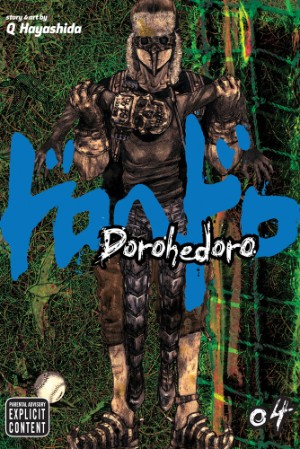

Manga Spotlight: Dorohedoro

Volume 4

By Q Hayashida

Released by Viz

Personally, I'm not big on year end top 10 lists. I'd rather spend the time covering releases that I haven't gotten to, and really, I can't remember what came out in a given year and as such don't really value years as a unit for measuring or comparing media.

Still, I have to say that Dorohedoro is a recent favorite. Not for being a great story or deep and meaningful, but for being weird, and clever; unlike anything else and well crafted to boot. Basically, a dark, demented embodiment of the qualities that drew North American's to anime and manga, engaging characters in a distinctive presentation. It's a singular, screwy wonder that makes me glad to be a manga reader and thankful that its creator is working in the medium.

Dorohedoro is set in a world no less creative or amazing than Tim Burton or Clive Barker's inventions. In The Hole, a bleak dumping ground for the human guinea pigs and prey of a caste of masked magic users, a lizard faced man stabs and eats sorcerers in search of the person who robbed him of his memories and transformed him into a reptilian freak. This can be thought of as an even bloodier, even stranger Oldboy. The fact that one of the characters wears a suit and fights with a hammer contributes to that (the 1999 Dorohedoro comes between the '96-98 Oldboy manga, which didn't feature the famous hammer scene and before the 2003 movie, so, the resemblance is probably coincidental).

There's plenty of red meat for a gorehound to sink their teeth into here. There really aren't that many sensationally violent manga still making their way over to North America and among the few that we do get, this is a prime cut, with plenty of queasy looks at the cross sections of severed limbs and spines, not to mention cases of major lacerations, disembowelment and punctured necks.

However, the visceral bloodiness is hardly the end of Dororohedoro's appeal. It's not manga that ran in Tenjo Tenge's Ultra Jump. It's from Ikki, an alt anthology that emphasizes experimentation and freedom.

The good example of how the manga all comes together is the volume's opening chapter, which tells the back story of the Shin, one of enforcer heavies for the manga's antagonists (a href="http://media.viz.com/flash/omv/index.php?x=dorohedoro/omv19">free online here). Here's a guy who wears a heart shaped mask (as in the organ, not the symmetrical, geometric shape) along with Tarantino movie-ish suit and the aforementioned hammer. He's respected, and a bit more, by his amazon junior partner and well regarded by his well to due boss. He's a relatively well adjusted and nice-ish guy by the standards of Dorohedoro and for a guy whose career is to wade into close quarter combat and crack skulls with a carpentry tool. The character isn't a convention case case or a nice guy who flips switch or a beast wearing swearing a smiling mask. As with everything in Dorohedoro, the slightly nebbishy guy can charge dangerous foes without hesitation is of a piece.

In this flashback, residents of The Hole used to fight back against Sorcerers, and as such, Neighborhood Patrol, clad in hazard suits who go at Sorcerers with axes and put with the aims of putting their subjugators-to-be's heads on pikes. They're brutal and homicidal, but without them, residents Hole winds a collection of human fodder for the magic users.

The other thing to be familiar with here is Dorohedoro's unique magic system, in which Sorcerers possessing "Black Matter" in their blood. This emanates as smoke, which causes various effects, like healing or turning people into mushrooms or lizards.

In Dorohedoro, people in fights are inevitably going to be profoundly wounded. A claw through the neck, a knife through the guts, or the like. Sometimes the violence is magically reversed, casting it as a disturbing Looney Tunes venture. Sometimes they don't get better, establishing a biting bit of ickiness. This chapter has some of both. Guys in blast shields get fatally picked apart with a hammer. And, the chapter has Shin sitting in a pool of own blood, with bits of arm littering the floor, holding a tourniquet in his teeth.

For a series that brutally mistreats its cast, Dorohedoro has a real affection for the characters. There's an obstencially heroic crew from the Hole and their sorcerer antagonists. While the two sides are actively about the business of savaging each other, the manga is not just looking for them to channel reader bloodlust.

Later in the volume, Shin's partner Noi gets pretty mess up and the crew goes to a bird face muscle man to fix her. The madman hops out of his hanging cage, hugs the gang's boss, En, and begins concocting a demonic homunculus to cure Noi. The most important part is a bit of organ from the person who she most cares about. En to Shin "It has to be one of us. Since your organs are already hanging out, give one up!" (in fact, Shin got major facial lacerations and a clawed through the guts in the battle leading up to this.) So the bird guy snips a bit off of Shin's hanging intestines, and makes the homunculus, feeds it to the unconscious Noi and instructs Shin to think of his and Noi's most precious memory together. "I guess it's that time, right after we first partnered up, that we got the shit kicked out of us on a job and fell off a a cliff on the way home."

This is shonen principals ad absurdum. The cast, both the partnership of good guys and ad hoc family of baddies, are endearing because their such fascinating bizarre combatants, and, especially, they're endearing due to of their camaraderie.

The manga kindof goofs with it. It can be jokingly lovey, and I haven't been tongue in cheek when, in the past, I describe it as moe, considering the all the fond fun it has with a sullen, skull masked, brain damaged young woman. At the same time, much of it feels genuine. To my mind at least, in its demented way, it's even more delightfully inclusive than something like One Piece. It's all part of the warped fun that Hayashida is brining into this group of likable monsters.

A similar principle of both sides being real appealing draws applies to the world of Dorohedoro as well as its characters. While the series might be set up as have and have nots, subjugators and subjugated, it's a not a polar cosmology of paradise over world and infernal under. Both are idiosyncratic places, full of fractured curiosities. The Hole has institutional environments such as meat lockers and hospitals, tunnels where you can find things like a man sized water bug in basketball shoes, and the dwellings and social spaces are all made up of what looks like found material; any barbed wire, board and sheet metal that can be stuck together. In contrast, the sorcerers’ over world is whole architecture, with proper shops, arches and such, but broken, grimy and build up on termite mounds of crazy. An example of this is that muscular bird guy. He lives in a giant bird cage hanging from the ceiling of a rotunda. Also on the ceiling are real avian cages. Classic statues of demons circle the walls. On the floor is a dresser, a cafe table, dirty t-shirts (bro is never shown wearing anything on his top half), and bird shit.

All this liking and fascination takes Dorohedoro in a direction that is not driven by story or even characters. Hayashida certainly pays attention to both dimensions. The manga does develop an overarching plot, and more generally, it never abandons good story telling. But, really, what Dorohedoro is driven by is its author constructing weird, wonderful episodes. The fact that this volume advances the plot is not going to be as well remembered as the scene of Shin hacking off his own arms, the appearances by lap dog with a Hellraiser-esque mask named Judas' Ear or, especially, two sorcerers clandestine entrance into a beer league Hole baseball game.

The episode of Dorohedoro are not random or inconsequential. They're creative

Running on that engine, what you get from Dorohedoro is a Dragon Ball for adults. Not late, calcified Dragon Bal. Early, any berserk creation scenario that sparked Akira Toriyama's mind Dragon Ball.

There is a sense that manga makes it big when its adapted. Yet, while live action movies/TV, animation and video games can certainly do ever more fantastic things, manga/comics still have the distinction of being the sequential visual medium that is only limited by the skill and imagination of the artist. Q Hayashida has both the imagination and the skill in terrifying abundance, and her vision of a mucky, bloody, warped wonderland gets to the heart of that potential, then rips out the still beating organ. It's difficult to imagine her Dorohedoro cropping up or being well served by another medium. Hayashida's Clive Barker-ish, America McGee-ish, vision could be and has been featured in video games, Shadow of the Damned to named a recent example, but it's here that her work is not mediated by budget and, running in the Ikki, barely mediated by supervision. It's fortunate for fans of manga and for fans of freshly cracked spectacles that we get this sort of undistilled. It almost seems like a favor.