Ahoy, squirts! Quint here, taking a break from Hobbiting to bring you something really damn cool if I don’t say so myself. Marty Feldman was a genius, one of the very best comedic character actors to ever grace the silver screen. I was first exposed to his particular brand of lunacy as Igor (it’s pronounced “Eye-gore”) in Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein.

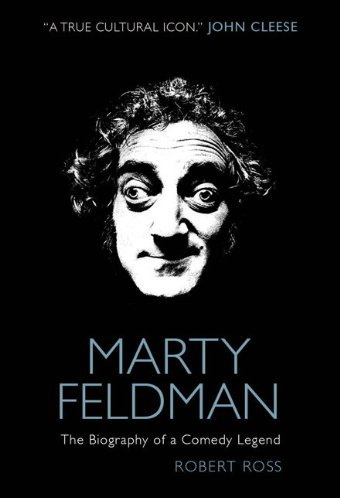

Feldman was preparing his own autobiography when he died and recorded extensive interviews for it. Author Robert Ross takes those elements and expands upon them, interviewing Feldman’s colleagues, friends and family for this new biography called Marty Feldman: The Biography of a Comedy Legend.

Titan Books has given us a passage to post here all about Feldman’s involvement in Mel Brooks’ Silent Movie and it’s a great read. I haven’t read the book myself, but will absolutely put it on the top of the stack when I get back to America.

Enjoy the passage! The book just came out and is under $20 right now.

The premise of Silent Movie is simplicity itself. Mel Brooks cast himself as washed-up film director Mel Funn. His attempt to sell the idea of a silent movie as his comeback project meets with disbelief from the studio head (played by Brooks’ old television boss, Sid Caesar). Recklessly promising to include all the biggest stars in Hollywood in the film, the director goes off to persuade the likes of Burt Reynolds, Anne Bancroft and Liza Minnelli. “Lots of stars did guest shots in it,” said Marty. “Even Paul Newman. There’s one scene with him where we have a chase in motorised invalid wheelchairs. It’s wild. He liked the chair so much he took it home with him. Doesn’t sound much, maybe, but each chair cost £20,000.”24 The most delightful star cameo of all comes from French mime artiste Marcel Marceau. Having made a career out of never speaking, he utters the only dialogue heard throughout the film. When Brooks telephones him to enquire whether he wants to appear in a silent movie he simply says: “Non!” As Variety reported: “The slender plot... is basically a hook for slapstick antics, some feeble and some very fine...”

Alan Spencer remembers that “Marty loved the company of other comedians. He would learn from them. I was on the set of Silent Movie a lot and he and Marcel Marceau really hit it off . They would be in the corner exchanging routines. They spoke the same language. The language of physical comedy. I remember Marty watching Sid Caesar work and in-between takes he would give Sid a few comedy ideas to work into his routines. They were all part of the same club. Marty was amazed to be working with some of the old school comedians. Fritz Feld was playing the Maître d’. He always seemed to be playing the Maître d’. But he had been working in Hollywood since the 1920s. He came over to Marty to introduce himself and say what a big fan he was. Marty couldn’t believe it. He was so flattered. ‘You’re a fan of mine? I’m a fan of yours!’ Marty would always do that. He would instantly deflect the conversation towards you. My friends at school would never believe that I knew Marty, and he would invite them to the set and be lovely with them. Even when friends of mine might meet him independently, they would say that they were friends of mine and Marty would say, ‘Then you have very good taste!’ Often when I was with him talking about writing comedy I would say, ‘I can’t believe I’m actually here talking with Marty Feldman.’ He would look at me and smile and say, ‘Stop it, love!’ He wasn’t threatened by anybody. He was just so encouraging.”

A silent comedy made in the Hollywood of 1975 was about as perfect a project for Marty as could ever be conceived and, indeed, he mugs, gesticulates, grimaces and body pops throughout every sight gag in the book. His curly locks are almost continually dampened down under an old style flying helmet, his ever mobile body clad in a tight fitting tracksuit, his mobile eyes forever searching out the next attractive female. This is Marty channelling Buster Keaton and Harpo Marx as never before, and relentlessly for nearly ninety minutes. “I know how Buster Keaton fell on his arse. In the same way I do. We both fall on our respective arses because we thought it would be funny at that time. We didn’t write a thesis on it before we fell and say to the director, ‘Hang on, I can’t do a pratfall yet. I have to work out the motivations for my pratfall. The theory behind my pratfall. The art of my pratfall.’ You say, ‘There’s a mark on the floor, I’ll hit that mark when I fall.’ Bang. There you go. Anything you do is intuitive.” There is something very satisfying in seeing him clown on the Hollywood thoroughfares once occupied by his screen heroes.

But he was still modest about his place in the pantheon of great clowns: “I can’t get rid of the umbilical cord I have to Europe or to the European tradition that came to me via the silent movies – Keaton and Langdon and Laurel and Hardy,” he said. “I’ve had to accept the fact that I will never be as good as those people have been. That’s the hardest pill to swallow – that I’ll never be in the same league as those I admire.” Yet there was a stronger emotion about his favourite clowns. Certainly stronger than simple admiration: “I admire Chaplin,” he said, “but I never loved Chaplin. I loved Laurel and Hardy. If I could have chosen a couple of uncles, I would have liked Laurel and Hardy. If I could have willed genius, I would have been Keaton. But you can’t. And you can’t aspire to be that any more than the average organist can aspire to be Bach. They are so pure and so much above anything you understand. You can’t aspire to it. That’s the hardest thing to swallow. You say, ‘Well, all I have is me, and I have to do the best I can with that.’

Marty is knocked to the ground, double flips and is catapulted onto a crowded dance floor and at every turn it really is him doing those things, just like his slapstick heroes in the Hollywood of the 1920s: “I think if you can do a thing yourself you ought to. I think you cheat the audience otherwise,” he said. “It’s part of your responsibility. It’s what you’re paid for. I like to do my own stunts when I can but I couldn’t do anything very specialised. If I had a tightrope walking sequence I’m not a tightrope walker and I couldn’t learn in time to do the movie but if it’s a matter of falls and jumps and leaps and crashing through things then, yeah, I’ll do that myself.”

“I had arguments with Mel about letting me do my own stunts. A stuntman can do them better than me. He can do a marvellous graceful fall but he can’t do it funny. It’s not his job to be funny... I have funny feet. I have funny legs. Jacques Tati said: ‘Comedy is mainly a matter of legs.’ I think he’s right. If you’re a clown you use every part of your body. If the director chooses to use a close up of me... I’m still using the rest of it. Like a piano has eighty-eight keys, I’m using all of the keys. The director chooses which part he wants to photograph but I use every part – that’s my instrument.”

Although again he was not featured on the list of scriptwriters, Marty’s influence is all over Silent Movie and, tellingly, The Marty Feldman Comedy Machine writers Rudy de Luca and Barry Levinson joined Mel Brooks and Ron Clark on the script. The Monthly Film Bulletin was left rather unimpressed by it all. “Brooks’ grotesquely lunatic style of comedy has little real connection with the silent clowns his film supposedly celebrates: one would search long and hard through the works of Chaplin or Keaton to find a frog leaping from a breast supposedly throbbing with romantic passion or an outsize fly winging its way from the top of an Acme Pest Control van to a restaurant customer’s soup... The film is further harmed by having a triumvirate cutting the capers rather than Brooks alone: all the nearest jokes are centred round Brooks himself... or appear as throwaway details... while Marty Feldman and Dom DeLuise only provide unfunny mugging. Despite the large number of agreeable gags, it’s hard to join in the closing festivals... the comedy seems too ingratiating, the clowns too self-satisfied.”

This completely misses the point. Silent Movie was a film about the extreme audacity of Mel Brooks actually making a silent movie in the Hollywood of the mid 1970s. It was one long joke, both in terms of a skilful re-imagining of the slapstick traditions of the past as well as at the expense of the studio boss at 20th Century Fox. The very idea of anyone making a million dollar, colour silent movie in “this day and age” is ridiculous. The fact that Brooks and his little knockabout gang made it work both artistically and commercially is nothing short of a miracle. No wonder Marty once dubbed Brooks “an incredibly intelligent pixie.” Marty’s deadpan salute to his comedy roots is at the very heart of the film. He effortlessly holds his own alongside veteran masters of the art like Harry Ritz of the Ritz Brothers and Fritz Feld of the legendary “pop!” In that beat-up old car careering around the Hollywood hills, the stars embrace the legacy of the Ritzes and the Marxes and the Stooges. There is even a dash of Morris, Marty and Mitch about them. And as the director, Brooks takes full advantage of Marty’s unique, mobile, funny face: “The only way you could hide from Marty was by standing right in front of him,” he said. “He was the very opposite of cross-eyed. He just couldn’t see you if you were stood right in front of him!”

There were times when hiding from Marty was Brooks’ only respite. Tempers had flared up during the making of Silent Movie and at one point Brooks, who was often given to phrases in the extreme, muttered: “Marty was heaven and hell to work with. He is probably the most complicated human I’ve ever met. [He] has peripheral vision in his soul.” Alan Spencer believes that: “Mel Brooks was a good person for Marty. They were opposites but both had great creative integrity. Mel knew how hard Hollywood was for Marty.”

The love-hate relationship between Marty and Mel Brooks may have gone deeper than just artistic differences, however. There was something Freudian about their relationship: “I’m… drawn towards Mel Brooks,” Marty admitted. “With all the things that are wrong with Mel, he has such an energy. He’s volatile. There’s no container big or strong enough to put his energy in. We’re totally opposite. I’m the introvert; he’s the extrovert. That’s my father’s generation. That’s the generation that came out without any education, that hustled and pushed and said, ‘I want to get to the top of the line’ – and got to the top of the line and pushed their way beyond it. I recognise so much of my father in him.”

A year after Silent Movie was released Marty explained that: “I’ve worked with Mel Brooks twice. I’ve done two movies with him... Mel has a great instinct for comedy. There’s a Yiddish word ‘tummler’. There’s no translation into English... Mel talks comedy. He can demonstrate it more than he writes it and his instincts are usually right. You can’t explain why but you can’t explain comedy. You talk about a sense of humour so therefore it can’t be defined and all I know is when Mel says: ‘Let’s do it,’ chances are he’s right, even if you don’t know why. He knows something. Possibly he has his finger up the pulse of the American public! You can take a pulse anally as well... his humour is a little broad but he knows what people will laugh at. There’s some kind of instinct which is nothing to do with talent, it’s something separate. Clowns sometimes have that, like musicians have a sense of what swings. You know the old story about Duke Ellington when a woman said to him, ‘What is jazz?’ He said... ‘If you have to ask, you’ll never know.’ Well, it’s that. It swings or it doesn’t. If your foot taps it swings and if you laugh it’s funny. Mel has that. What ever it is he’s got a lot of it.”

Marty would never again star in a Mel Brooks film. Young Frankenstein had become such a hit at the box office that studios were falling over themselves to make parody films with the recognised Mel Brooks repertory company. By 1976 the inmates had well and truly taken over the asylum.

Can’t wait to read the rest! Thanks for the preview, Titan Books!

-Eric Vespe

”Quint”

quint@aintitcool.com

Follow Me On Twitter