I never would have guessed there would be so much science (and astronomy in particular) in THOR. And I was further astonished to find out that I know two of the science advisers on the film. Not only, that, but they had a great experience and were actually listened to and helped improve the film. So this week, in addition to my usual shameless self-promotion of my TV show, KNOWN UNIVERSE, I thought I’d tackle the Science of Thor!

THE SCIENCE OF THOR

As a comic book, Thor exists in the realm of imagination and legend. Different worlds are parts of a magic tree, populated by immortals, frost giants, and serpents, and bridged by rainbows. In this world the laws of physics take a backseat to enchantments and magic artifacts.

But a direct translation of the full operatic, color-saturated glory of the comic page to film often goes off the rails, because while in comics the reader is helping with his or her imagination, movies are a medium much closer to the real world. And there is an additional constraint for THOR. Thanks to the upcoming AVENGERS film, the lead character must coexist in a cinematic universe established by Jon Favreau’s relatively grounded IRON MAN.

Realizing this, Marvel and president of film production Kevin Feige, have eased audiences into their universe one “buy-in” at a time. For IRON MAN it was that one rich bastard could invent a flying, weaponized suit of armor. For THE HULK it was that gamma rays could turn people into monsters. For THOR it would have to be that there are different realms populated by nearly godlike beings. That meant that everything else about THOR had to be relatively grounded in reality. To achieve this significant feat, Marvel consulted not just one, but four science advisers: Sean Carroll (Caltech), Jim Hartle (UCSB), Kevin Hand (JPL), and Kevin Hickerson (Caltech).

In preparation for this article, I talked to the two of them I already knew: Sean Carroll and Jim Hartle. Sean is a cosmologist at Caltech, and contributes to one of the most popular blogs in astronomy, Cosmic Variance. Jim Hartle is emeritus faculty in my own department (UCSB physics), and an expert in general relativity, quantum mechanics and many other things. They are both top-notch scientists, and by all accounts were consulted widely and actually listened to on the development of THOR. It is clear to me that they really improved the film.

Carroll, Hartle, and Hand were brought in early, even before a script was completed, and met in LA with director Kenneth Branagh and some of the film’s creative team. The group brainstormed ideas to literally and figuratively bring THOR “down to Earth.” The filmmakers already had some notions of character and story, but together with the scientists they decided on a few ground rules for the universe and ways to achieve their story goals with as much plausibility as possible. They made some bold decisions, including the ideas that the nine realms would be physical places (essentially planets) set in a universe much like our own, and connected by wormholes, that the apparent magic would be achieved by advanced artifacts, and that the character of Jane Foster would be changed from nurse to astrophysicist. As the story was developed, some of the scientists were then consulted on how to turn these ideas into reality. Finally, later in development, Kevin Hickerson was brought in to consult on the creation of some of the artifacts.

In this article I’ll cover some of these bold decisions, including the reasons they came about and add my own commentary about the scientific plausibility of how they worked out in the finished product (after a certain point the scientists didn’t know what happened to their ideas and had to watch the finished film to see).

THE NINE REALMS ARE PLANETS (KIND OF)

One of the decisions I like best in THOR was to set the nine realms in something approximating the real world. In the mythology they are something like different planes of existence, akin to heaven or hell (one actually is Hel). But in the film, it seems that at least some of the realms are planets. The Bifrost Bridge is no longer a rainbow you can walk on (though the energy-gorged path leading to it kind of is) – instead it generates wormholes, allowing Asgardians to travel from planet to planet. This is a wonderful idea. I love that the Bifrost is this giant piece of machinery that has its own observer, guardian, and operator, Heimdall (played perfectly by Idris Elba). This is Heimdall’s observatory as well as portal. It isn’t too different from real observatories – complicated pieces of machinery that let us see far into the universe, staffed by astronomers and telescope operators. Of course, we don't get to dress like this:

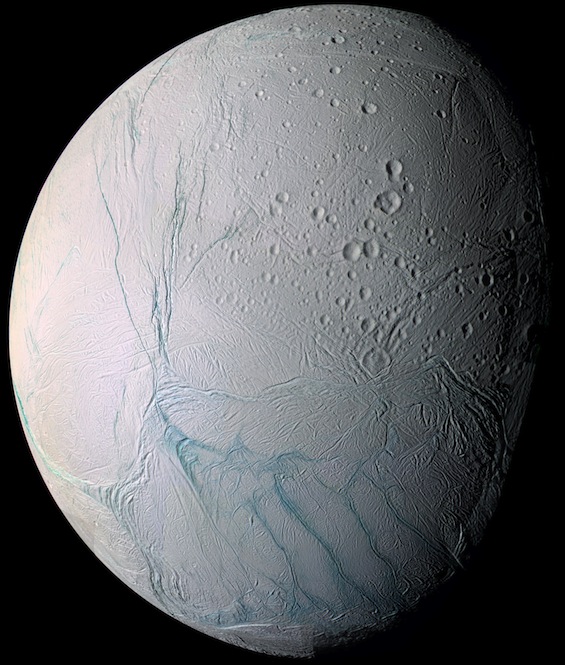

And I love the idea of a planet of frost giants. Such a place might be farther from its sun than Earth (or around a less luminous star), so it is colder. And it might be smaller, so it has less surface gravity, allowing humanoids to grow taller. We know about several ice-covered moons a lot like this in our own solar system, like Europa and Enceladus, and it seems to me that images of these moons were used as the inspiration for establishing Jotunheim, the planet of giants.

False-color mosaic of Enceladus, a moon of Saturn, taken by Cassini.

The filmmakers almost went a bit too far interpreting the realms. According to Sean, they were thinking of making Jotunheim a disk instead of a sphere. Then when Thor smashes them and sends them flying, they would fall off the edge of the disk. That might have looked cool, but then you have to ask, “Where is the gravity coming from?” This is a great example of how consulting scientists can help prevent a film from losing all credibility by stumbling into absurdity.

But are all the realms planets? This went right past me, but Sean said Asgard is represented as a mountain on top of something that looks like a galaxy. This is something close to the mythological version of it (Gods, like the rich in Santa Barbara, love to live on mountains). He says it is so far out there that it reads as artistic license. Maybe, but why make it look like it is on a galaxy, which is silly? Galaxies are mind-boggling enormous. Maybe there is another explanation. I grabbed this screen shot of Asgard from the first trailer:

Notice the planets in the daytime sky. One is a gas giant. That would make the other one a moon of the gas giant. The only way for Asgard to have such a planet so large in the sky is if it is a moon of it. If moons are large they get crushed down into a sphere by gravity. Asteroids can be oddly shaped because they are small. But the biggest one, Ceres, is actually so large that it is spherical (it was considered a planet in the later part of the 1700s). Deimos, a moon of Mars, is a captured asteroid that is small enough that it isn’t spherical. Asgard, with its mountainous form, must be a small-ish moon of the gas giant. Of course, the problem with that interpretation is that it would have very low gravity. But surely the advanced Asgardians can solve that.

Like most asteroids, Gaspra, left, is too small to be crushed into a sphere. But the largest asteroid, Ceres (center), is spherical like a planet. Meanwhile, Deimos, one of the moons of Mars, is clearly a captured asteroid. It is so small it can remain nonspherical.

The filmmakers did cram lots of cool stuff in its night sky of Asgard, inspired by real astronomical observations. I need to see THOR again to catch exactly all they put in there.

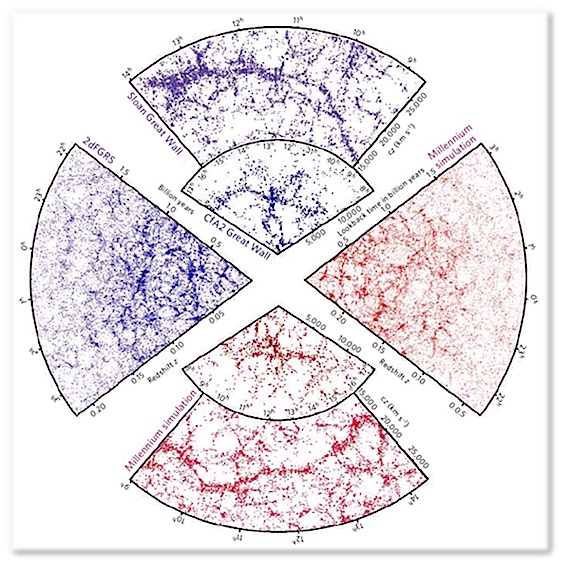

Are these planets that make up the nine realms in our galaxy, the Milky Way? Normally, you’d think so. Of course all the planets we know about are in our galaxy. And when Thor draws a picture for Jane of Yggdrasil, the world tree connecting the realms, I took that to mean that they were spatially somewhat close together. But there is conflicting information. At the end of the film, they show worlds connected together by what looks like a web. This is meant to evoke the large-scale structure we see in the universe. Galaxies are not dispersed randomly in the universe – they are actually grouped together in what looks like a web, with large voids in between. It seems the filmmakers are trying to equate Yggdrasil with this cosmic web. If so, it implies that the planets of the nine realms are located in different galaxies. But there are billions and billions of galaxies. Why only nine realms? Maybe they are the only ones that are interesting or important.

Galaxies aren’t distributed randomly, they are arranged in filaments around voids, and the structures almost look like the branches of a tree. Here each point is a distant galaxy. The blue quadrants are real data from galaxy surveys, while the red quadrants are from the Millennium simulation (see below).

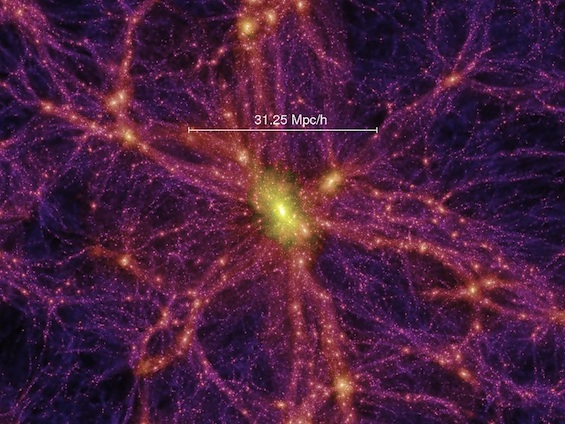

A frame from the Millennium simulation of the large-scale structure in the universe. The scale bar is 140 million light-years. This shows the mass, not the light, in a cluster of thousands of galaxies. Sky surveys of galaxies have shown that galaxies are aligned in filaments like a cosmic web.

Jim Hartle said he recommended that the realms be associated with D-branes. Branes are basically groups of dimensions embedded in a higher dimensional space. This essentially amounts to the realms being in other dimensions. That would certainly better explain why there are nine realms. But it wouldn’t have related Yggdrasil to the large-scale structure of the universe.

At least part of the time, the wormhole is traveling through out galaxy. Check out this shot from the trailer:

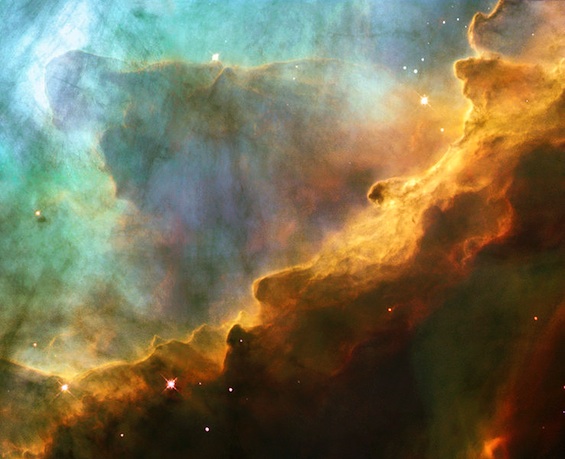

Notice those nebulae. They are quite similar to Hubble Space Telescope images of gas clouds in our own Milky Way, like this one of the Omega Nebula (M17).

Maybe the treelike structures shown at the end of the film are supposed to be gas clouds in our own Milky Way. Here’s an example of “the spire,” a giant pillar of gas that is forming stars, associated with the Eagle Nebula.

Image of “the spire” in the Eagle Nebula (M16), as seen by the Hubble Space Telescope.

Ultimately, Sean, Jim and I agreed that the film is ambiguous about where or how the realms are arranged. That’s fine with me. Branes (an extension of string theory) may be as fanciful as Asgard itself. But part of me feels like it is a missed opportunity. Sean and I were imagining what we’d say to Thor once we realized he was not from Earth. Can you imagine Jane the astrophysicist geeking out when she realizes where Thor is from? If he’s from another part of the Milky Way, or a distant galaxy he could tell her about the different perspectives and different stars he can see from there. Or if he’s from another dimension, or could have verified braneworld cosmology, he could have instantly handed her a Nobel prize by explaining it to her. Thor explaining cosmology to an astrophysicst would have been worth the price of admission alone. He’s supposed to be kind of brutish and headstrong, whereas she’s the intellectual, yet he knows infinitely more than her by virtue of being from an advanced civilization. I know they had that scene where he sketched Yggdrasil but it was lame compared to what it could have been.

Incidentally, if the Asgardians are interplanetary travelers that were mistaken for gods when they visited Earth in the past, then it is perfectly reasonable that they don’t all have to look Norse. That sure makes these people criticizing the casting of Idris Elba for not looking Scandinavian, before they’ve even seen the film, look silly.

MAGIC=TECH

To avoid magic as much as possible, THOR invoked Arthur C. Clarke: “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” The premise is based on the idea that Thor and company aren’t gods, they just have much more advanced technology than we do. When I first heard that this is what they were doing from Harry, I was a bit skeptical. Why not just leave a bit of magic in the world? With the LORD OF THE RINGS and HARRY POTTER, audiences have shown they can get behind magic in a big way.

There are good story reasons for avoiding magic here though. Aside from the ones mentioned before, we now know that the crossover between Marvel films, at least AVENGERS-related ones, is going to be extensive. Loki is apparently going to be a villain in the AVENGERS. The Cosmic Cube will play some role (summoning the Skrulls?), and apparently it shows up in CAPTAIN AMERICA as well. CAP is another film that needs to be fairly grounded in reality to work well, so having the Cube as an artifact is the only way to go.

Thor also needed to lose his powers at one point in the film. Having them tied to his hammer made sense for that. There is some precedent for this in the comic, when an alien, Beta Ray Bill, proves worthy to lift Mjolnir, and suddenly is granted Thor’s costume and powers.

They key to making this work is not explaining things too much, i.e. avoiding “the midichlorian solution.” It may seem silly to us that Odin can say something to the hammer and it can know whether Thor deserves to wield it. Or that Thor’s costume magically flies onto him when he’s in possession of a hammer. Or that there is a hammer that can give you superpowers. But, as this Cosmic Variance post (not written by Sean) points out, that’s the point! It is so advanced that it looks like magic to us. If it wasn’t, it would just be technology. Imagine how an iPhone would look to someone even from the 17th century. Magic.

There is only one science-related clue about Mjolnir in the film. They say it was “forged in the heart of a dying star.” That sounds cool, but doesn’t tell us much. Actually, all elements heavier than iron were forged in what could be called dying stars. About half were formed in massive stars on their one last hurrah before they die (when they are on the asymptotic giant branch), and the other half are formed only in a supernova explosion. That is the only place they can be created. So if you have some gold jewelry, that too was “forged in the heart of a dying star” -- in a supernova. At least we know Mjolnir is heavier than iron.

Incidentally, Mjolnir has some pretty serious power requirements. I know this is over-analyzing, but I can’t resist throwing in a little science. Mjolnir gives Thor the ability to call storms and lightning. This is no joke. In a typical thunderstorm, about a billion pounds of water vapor is lifted to great heights. When the water condenses it releases as much energy as a city of 100,000 people use in a month. Then again, maybe Thor can only influence weather patterns that already exist.

JANE FOSTER IS AN ASTROPHYSICIST

In the comics, Jane Foster was a nurse, but now she’s an astrophysicist. I love this change. Comic book characters are a product of their times, and sometimes they need some freshening up. In 1963, when Thor debuted in Journey Into Mystery, nurse was one of the few “acceptable” professional positions for women. One need look no farther than STAR TREK to see this bias in action. When the STAR TREK pilot was delivered in 1965, Majel Barrett played “Number One,” second in command to Captain Pike. However, executives didn’t like, or didn’t think audiences would accept, a woman in such a strong position, and her role was converted to Nurse Chapel when the series went into production.

In 1963 there weren’t many women in astrophysics. But today a quarter of the membership of the American Astronomical Society are women. This doesn’t tell the full story though. As you go to younger and younger levels in the profession, the percentage of women increases. Around a quarter of young faculty members in astronomy are women, but around a third of astronomy PhDs awarded are to women, and about 40% of bachelor’s degrees go to women. It takes some time to go from Bachelors to PhD to professor, so this says that things are changing fairly rapidly.

But what has changed in the last 40 years? Attitudes. Women are less often discouraged from going into the sciences. And girls now have role models to show it is possible. So I’m happy to see Marvel changing with the times. It better reflects reality today, and provides a great role model for girls aspiring to study astronomy.

So how is Jane Foster as an astrophysicist? She’s fairly well done. The character is a hell of a lot better than the Bond version of a scientist, slapping some glasses on Denise Richards and calling it good enough, as Natalie Portman herself pointed out. She’s serious, driven, and enthusiastic about her research. She, and the writers, got the tone, and her dialog down nearly perfectly. This is partly because Marvel consulted real scientists. Sean Carroll said they asked questions like, “What kind of position would she hold?” “Could there be tension with her academic supervisor?” and even, “What kind of posters does a young physicist have on her apartment wall?” She even uses a lab notebook, just like a real scientist. Why would scientists be using pencil and paper in this digital era? When I was at Lawrence Berkeley Lab, I think it was George Smoot (now a Nobel Laureate), who convinced me of their importance. They are often consulted in court cases over intellectual property or patents, and sometimes even to determine credit for Nobel Prizes. Indeed, national labs today still encourage their scientists to keep hard-copy notebooks.

This isn’t to say there aren’t a few nitpicks I have about the Jane Foster character. One bit of dialog sticks out like a sore thumb. When describing how the stars look through the atmospheric disturbances, she says she sees stars, “but not our stars. See this is the star alignment for our quadrant this time of the year, and unless Ursa Minor decided to take a day off, this is someone else's constellations.” First, astronomers would always say “constellation,” not “star alignment” – it isn’t like they are moving relative to each other. And secondly, no astronomer would ever say, “quadrant” when talking about the Milky Way – that is pure scifi-speak. Sean says that dialog was added after he was done consulting on the film. Jane also insists on calling wormholes, “Einstein-Rosen bridges.” While that is technically correct, every scientist I know calls them wormholes. But you can see the reasoning for the wording change here. While these things are a dead giveaway to a scientist that this is only a movie approximation, I think mainstream audiences wouldn’t have any idea that the jargon isn’t perfect.

When one of my female astrophysicist friends, Haley Gomez, saw Thor, she tweeted, “Next time I'm in my office ’looking at particle data’ I will make sure I'm wearing false eyelashes like Jane the Astrophysicist.” I must confess this went right by me. Indeed, there is a fine line between “looking Hollywood” and ringing true as a scientist, but as far as believable portrayals go, I’ll take Natalie Portman in false eyelashes over Denise Richards in glasses any day.

As I touched on before, another thing Sean pointed out is that one missed opportunity is that when Jane figures out that Thor is from another planet, in addition to swooning over his biceps, she should have been peppering him nonstop with questions about advanced physics, which clearly his people has mastered. Even if he was a bad student, he’s likely to know much more than she does. Imagine even a high school dropout of today talking to someone from the stone age.

So all in all, I enjoyed THOR, and especially its dedication to making things as plausible as possible within a fanciful universe. By consulting scientists, the filmmakers avoided disaster, elevated the film with clever ideas, and even gave their characters more depth and made them more believable. And in the process they might help inspire the next generation of scientists. If only all movies could do the same.

Now the question is: what’s next? Are we going to get to see some cool new alien worlds in THE AVENGERS? (Sean says the script is awesome, but didn’t leak any details). And is Marvel’s aversion to magic specific to the story requirements for THOR? Surely Doctor Strange have magic (he has to, right?). At any rate, Marvel is doing a great job of building an interesting, plausible, and interconnected universe. Maybe it isn’t so bad that Fox and Sony have the rights to so many of their characters. SPIDER-MAN and X-MEN are like licenses to print money – even bad versions make a mint. But without them, Marvel is forced to go deeper into their repertoire and explore lesser-known characters to make films. And they spend more time getting them right. So far they are doing a pretty good job.

- Andy Howell aka Copernicus