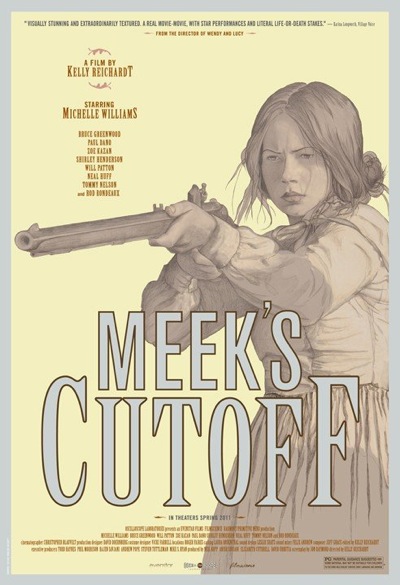

Walking through the posh Sunset Marquis in West Los Angeles three days after seeing Kelly Reichardt's western, MEEK'S CUTOFF, I am struck by the abundance of water. Swimming pools, fountains, condensation-streaked glasses filled and re-filled for patrons in the hotel restaurant: there is ample opportunity for hydration. Not so in Reichardt's film, where three families attempting to navigate the Cascade Mountains via wagon in 1845 veer off-course at the dubious insistence of their blustery guide, Stephen Meek (Bruce Greenwood), and, as a result, lose sight of drinkable water. Bad for them, bad for their oxen, and bad for the stray Native American they capture along the way. It's a desperate situation that only worsens as the wagon team presses on over rugged and increasingly parched terrain.

Given the unadorned aesthetic of Reichardt's films - from 1994's RIVER OF GRASS to the "Oregon Trilogy" just concluded by MEEK'S CUTOFF - it's a bit strange to be meeting her for the first time in one of the city's most luxurious hotels. But this is where she's been put up to do press, so here we are: seated comfortably in a semi-circle booth chatting about a film that required Reichardt's cast and crew to dodge rattlesnakes and other critters for three months in the Oregon High Desert.

"It's nice that anybody cares," laughs Reichardt. She's been discussing MEEK'S CUTOFF since the film played the late-summer festival circuit in 2010, and while she's grateful for the attention, it's clearly time to head off and make another movie. "You work really hard to figure out what you want to say in your film - and not say it," explains Reichardt. "And then you go out and talk about it for a year and explain everything." This includes the film's deftly-integrated political allegory, which, truth be told, I didn't consider at all during my initial viewing. I'm sure these elements will emerge when I revisit the film (which I plan to do during its theatrical run - if only because it isn't every day you get to see a new film shot in good ol' Academy ratio), but MEEK'S CUTOFF, like OLD JOY and WENDY AND LUCY, is primarily about observing people interacting with each other and their surroundings. Though the cast includes a few recognizable actors (Michelle Williams, Paul Dano and Zoe Kazan), from the opening, meticulously-composed full-shots of the characters doing their daily chores, the movie completely draws you in. Yes, MEEK'S CUTOFF moves at a contemplative pace, but, as Peter Bogdonavich once noted about John Cassavetes's films, "Watching people takes time." And it's rare anyone takes that kind of time nowadays.

Once Reichardt and I finished working through the allegorical component of her film (a discussion I've omitted since I think it's more rewarding if one teases these elements out on their own), we discussed the arduous process of shooting this film and how she managed to keep it naturalistic despite the presence of familiar faces. We also discuss her view of the "mainstream" and whether or not she could see herself merging with it somehow.

Mr. Beaks: In terms of what you're trying to say with your films, I had the same experience with MEEK'S CUTOFF as I did with OLD JOY. I didn't see them as allegorical. They were experiential. Then I read reviews in which they were deconstructed, and realized there were levels to the films I hadn't considered - which is strange because I impulsively deconstruct almost every film I see. But for whatever reason, I just don't engage your films like that - at least, not initially.

Reichardt: That's fascinating. What you're describing, that's how I experience Jon's writing - even his novels. I sort of take them at face value, and then I go, "Oh, yeah!" I sort of think of that as the beauty of Jon Raymond, and the challenge of turning those stories into films.

Beaks: Was this "Oregon Trilogy" premeditated?

Reichardt: No. (Laughs) There was this vague idea of a trilogy, but we're writing something else for Oregon now, so I'm like, "What are you going to call that, John?" It's just an excuse for Jon to keep writing about Oregon. There was a vague sense of a trilogy, I guess, by the time we were at WENDY AND LUCY. We started thinking about what we would do next. These themes... I think we'll probably move away from the "lost" theme, but those themes are in my films without Jon. They do have their common threads, and they were made through this particular time that I kind of see myself summing up an America.

Beaks: Long-playing full shots are so rare nowadays - and not necessarily because people lack the skill to do it. There's a phrase used by studios: "vacuuming out the space". They don't want shots to linger. And what they're sacrificing is the opportunity to watch characters inhabiting their surroundings and interacting with one another in a natural-seeming way.

Reichardt: For this story, that's a necessity. That's what it's really about: you're up against the elements. I don't even know how you could do a story about going west without those [shots]. The landscape is something you have to contend with. It's a battle. It's not just a pretty backdrop; it's the river you have to get across, or the mountain you have to get your oxen over. It's filled with rattlesnakes and prickly stuff, and you have to get through it in your dress. They're surviving the landscape that's inspiring them to move on at the same time.

And that's how it was working in it. This desert kicks your ass. It really does. It's 110 degrees, and then it's 30 degrees, and then it's sleeting. And then you drive home at night over this playa with this sunset, and with this group of people you worked so hard with, and you're just like, "Wow, it doesn't get any better than this. (Pause) God, we have to do this tomorrow? Ugh!" These things are very wrapped up in each other. When you're out there, you almost understand why there's a Bible belt, and why the religion is where it is. There's big skies and insane sunsets... and tornadoes. How can you deny something bigger at work - whatever that is? And at the same time, there's these practical things you have to do. You have to be self-reliant to move through it.

Beaks: This is what some people might call a "landscape film", but it's shot in Academy ratio. Why did you decide to shoot the film this way?

Reichardt: I had a rule of no vistas. (Laughs) It was for a bunch of reasons. It seemed to make a lot of sense. I mean, just on an aesthetic level, I really like the square. I like the desert and the square. I was kind of inspired by Robert Adams and his American West [photography]. His photos and the square. It gives you this foreground: you get the height over the mountains and the sky. But it also worked for the vision that the women have in their bonnets, this lack of peripheral vision and this straight-ahead, no-nonsense perspective. And then also if you're traveling seven to twelve miles a day, and you have widescreen, it's like, "There's tomorrow! I can see it in the screen! And there's yesterday!" So this was a way of keeping you locked in the moment and not getting ahead of where the emigrants were. I think that helped build tension, because you could not see what was around the next corner. It just worked in a bunch of different ways.

Beaks: What draws your interest first: narrative or theme?

Reichardt: For this, Jon Raymond and I went out with this painter Storm Tharp, who took us out to this area of desert when we were making WENDY AND LUCY. I had sort of had this idea of WENDY AND LUCY happening in a desert town of - I haven't seen this film in years, but I had it locked in my head - VIOLENT SATURDAY, the Richard Fleischer film. As I remember it, the first shots of these high mountains locking in this town is so picturesque, and by the end it feels so repressive, like you can't get beyond them. It was a concept for WENDY AND LUCY that I couldn't quite pull off and didn't really quite work. But we had made a trip out to that desert, and it was so different from other deserts I had driven through in America. So I really was interested in shooting in that landscape. We kept saying, "For our western. Hahaha!"

And then Jon found the story of Stephen Meek. That was really intriguing. So the story, and the possibility of those characters was the next thing. But I really did want to shoot in the desert. In theory. (Laughs) So we started scouting and thinking about the realities of it.

Beaks: How immersed were you in the surroundings? Did you stay there?

Reichardt: Oh, yeah. My locations guy Roger Faires, moved out there for three months. And Neil Kopp and I started going out there regularly with Roger a couple of months earlier. Then Neil, the art department and I moved there a good six weeks before the rest of the crew came. It's a two-street town called Burns, Oregon. It's like the least-populated town in America. I think the industry used to be painting Winnebagos or something. But, anyway, it left, and now there's a lot of unemployment. So the town was happy to have us because we brought a lot of business. Basically, every single person you meet there has some Meek story in the past. Whether their ancestors were on the trail or not, somebody's connected to Meek in some way. Some of these people came and worked for us on the film, and it was really great. We needed them: ranchers and stuff who knew the land. We shot right where the immigrants were lost. We all stayed at this place called the Horseshoe Hotel - and it is shaped like a horseshoe. Everybody stayed there. There was one store where you can buy your eggs or your hunting jacket. And there was the Elks Lodge: that's where all the locals have their drinks at night, and that's where we ate dinner every night.

And then we'd drive about two hours off-road into the desert in whatever direction each day. The travel was pretty intense. They're all really-hard-to-get-to places - so the scouting was a really huge part of it. The big challenge of the film was getting everybody there each day - and that was obviously eating into my shooting day, the choice to go to these locations. And then for some scenes that needed water, we ended up chasing the water because we'd scouted big bodies of water and they were gone by the time we shot. The locals told us they'd be gone, but I just couldn't believe it. "I just walked across that creek, and it came up to my neck!" And then you watch it dry up. It seemed impossible. You just couldn't fathom that a body of water could completely disappear in a month's time, but it does.

Beaks: How difficult was it finding areas untouched by civilization?

Reichardt: That's not that hard. The area is pretty untouched out there. Occasionally our local guys had to pull up a fence or something. It's not even on an airplane path. It's quiet out there. Deathly quiet. You kind of wished there was something out there. Not airplanes, but... something. The sound design was difficult because it's so silent out there.

But that wasn't the difficulty. The real difficulty was the script says "The Desert", and you're like, "Whoa! The desert's a lot of different things, and it goes for three states." The hardest part was roping it in and finding the specifics of what a scene called for in the landscape - and getting away from this thing, like, "They're on a salt flat, and then they're surprised by something." It's hard to be surprised in the desert; you can see for a long way in the desert. So Jon would be in Portland, and I'd be like, "Jon, what do you mean?" And he'd say, "Wait a minute. Let me get this cat off my lap." He was all nice and cozy in his little world. (Laughs) The scouting that Roger had to do... we were still looking for spaces while we were shooting. And just convincing everyone to come along. You can't do a practice run, so you're like, "I wonder if we can get the animals there. We won't know until we're shooting." That's really stressful.

Beaks: So it was rough. Not quite on a level experienced by the families in the film, but... rough.

Reichardt: We went home and slept in a bed, but it wasn't like you couldn't get a hint of what it was all about. When we started scouting, the rattlesnake factor... I was like, "I'm never going to get over this." We had days where we couldn't shoot until the snake wranglers got the snakes out of the area. You'd catch five snakes in a little area before you're shooting, and then you're like, "Alright! Get the actors out here! Tell them it's all clear!" (Laughs) To me, once everybody was there, I had so much else to deal with that I was like, "Rattlesnake? Eh, bring it on!" But in the beginning, when it was just the three of us out scouting, it just seemed like there was a snake over everything. You'd convince yourself you're over-thinking it, and then there's a snake! (Laughs) And you can't tell where they're coming from! And the insects. You'd go home to your bed with your clothes filled with crickets. These are things I wouldn't have pictured myself overcoming so easily, but they become so low on your list of worries.

Beaks: How long did it take to get your actors acclimated to this way of life?

Reichardt: I'm not sure they ever got "acclimated" exactly. There was probably a zone in the middle. You were never going to the same place twice, and you would think, "We must've just had our hardest day." But then you realize they're all going to be days like that. Every time you change locations there's a new hump to get over - and just that it switched from 110 degrees when you started and went right to being thirty degrees, snowing and just so cold. We never stopped getting our ass kicked. We had a week of pioneer camp before we started, where they worked with the ranchers and learned how to drive the oxen. That was a huge thing. They learned how to build fires and pack their wagons and unpack their wagons and set up their tents - and just learn how to use everything that one carries with them so that all the tools made sense. We didn't want anything to feel like a prop. Nothing on anybody's wagon should've been something they didn't have a handle on. That was all done at this airplane hangar outside of town. I don't know why people didn't just leave. (Laughs) It was a very committed group of people. We didn't really have any luxuries. You couldn't hide from the elements.

Beaks: Bruce Greenwood's portrayal of Meek is amazing. When you're playing a character that outsized, there's always the danger of turning it into caricature. How did you two keep that from happening?

Reichardt: Bruce worried about that. We both did. We were trying to find that place in between. But everything that was written about Meek... I mean, he was a caricature. He was a bigger-than-life person. So how do you get a handle on that? How do you make someone bigger than life and not have it seem like bad acting? To me, Bruce Greenwood is a chameleon. He's so different in every role. It always takes me a minute to go, "Oh, that's Bruce Greenwood!" It was something that we never stopped trying to monitor and think about, but there was nothing to do but to just do it.

By the same token, there were a lot of dangerous things. Rod Rondeaux is practically naked in the whole film - and we tried to keep him as warm and dressed as possible. But I'd set up the shot with Steve MacDougall, the first-camera assistant, and then Rod would come in, and you'd put a bare-chested Native American with beads on him in front of a low-angle blue sky, and suddenly you're like, "Oh, shit! Am I making a cowboy-and-indian movie?" You're so afraid of the cliche and the shot. And to me, an actor like Rod Rondeaux... even as a person, he is inscrutable. He's not like anyone I've met before, and he's not like anyone I'm ever going to meet again. He's a mystery that you can't really nail down. So you just have to have faith that the essence of this person is going to come through and save me from this cliche that I'm grappling with. That's the part of it that's the experiment, and that's the part of it that makes it really scary and challenging and interesting. You need to be out on a ledge, and we were all out on a collective ledge.

Beaks: Did you always picture Michelle in this role?

Reichardt: Yeah, we wrote it for her. I knew I wanted to work with her again. I loved working with her on WENDY AND LUCY. When we were done with WENDY AND LUCY we were like, "When are we going to do next?"

Beaks: Do you storyboard?

Reichardt: Yes. I mean, I worked with this storyboard artist, this painter Michael Brophy, in Portland. And then sometimes I'll take an image from somewhere else completely. Some of it is montage storyboarding - I can't draw myself. It's so funny. People always say to us, "It just seems like you guys go out there and improv." And I'm like, "Really?" We have to move really fast, so I really have to be as on my game as I can possibly be. You can spend all the time you want in the location and picture how it's going to be in your mind and have your shooting notes and storyboard, and you still know when you get there it's going to be different because somebody else is going to be speaking the lines and there will be oxen moving. There will be enough to contend with. But I'm not a person who can draw all my shots. I use a combination of storyboards, location photos and photos from other places that there are things about them that I want to steal from. (Laughs)

Beaks: I have to ask where the idea for that epic dissolve early in the film came from.

Reichardt: I guess it's hard to say. I can't remember how it originated, but it was going to be my way of getting us away from the water. I wasn't sure whether it was going to work or not, so I had a back-up plan if I didn't like it. It's funny. It's a very traditional device in westerns for moving time along. It's just a tip of the hat to Anthony Mann or something.

Beaks: Have you ever considered moving toward material that might be more commercially accessible?

Reichardt: I can't really think of life in those terms, and I don't think Jon writes in those ways. I look at what's out there, and I don't see the place for my sensibility. I imagine we'll remain on the outskirts of the mainstream - which is fine. Not everyone can be in the mainstream. It's not out of some purism or making any point; I just don't think our ideas... when I look at what's in the mainstream, I just don't see where it's a great fit. That's fine. I can't even say I know what's in the mainstream, but I've seen some previews and stuff. They don't need me. It seems like they have plenty going on. I don't know enough to know what I'm not a part of, so I don't feel left out of anything.

Beaks: So you're satisfied?

Reichardt: Yeah. I'm making films with my friends, and nobody's really telling us what to do. What more can you ask for, right? That's pretty lucky.

And you're lucky because MEEK'S CUTOFF is out in limited release now, waiting to be discovered. It's one of four bona-fide masterpieces I've seen this year, so please get out and support great filmmaking.

Faithfully submitteed,