Bill Hicks was only allotted thirty-two years on this planet, and while he certainly made the most of them, his abruptly-ended stand-up career is a mess of what-ifs. When he succumbed to pancreatic cancer in 1993, Hicks was on the verge of comedy superstardom, inveighing eloquently against all manner of outrages: the U.S. government's incessant misbehavior, the mainstream news media's unquestioning coverage of these offenses, the evils of marketing, and, of course, the tyranny of organized religion. Hicks was a direct descendant of Mort Sahl and Lenny Bruce, prone to Sam Kinison-esque outbursts, but imbued with a calm, compassionate spirit - and after kicking drugs and alcohol in the late '80s, his act had clicked. The full range of his talents are on display in his landmark comedy special REVELATIONS, where Hicks artfully segues from bilious rage to a beautifully-composed (and shockingly un-mawkish) plea for peace, love and understanding. Though it might've seemed like it at times, Hicks wasn't a misanthrope; he was a humanist who abhorred ignorance and cruelty.

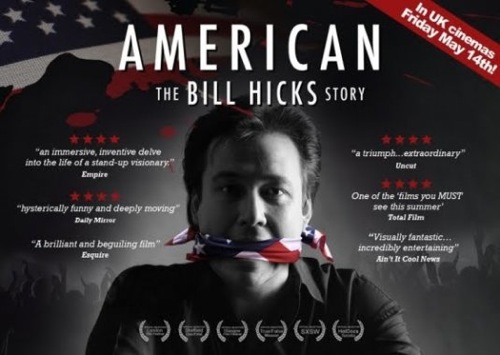

The evolution of Hicks's worldview is examined in AMERICAN: THE BILL HICKS STORY, a new documentary by Matt Harlock and Paul Thomas. The film eschews the expected talking-head format in favor of the animated-still-photograph approach utilized by THE KID STAYS IN THE PICTURE - which, as the filmmakers explain below, was a way of keeping Hicks at the emotional center of the narrative. It's the first feature-length documentary approved by the Hicks family (who've carefully guarded Bill's legacy in the nearly two decades since his untimely passing), and they've decided to make it intimate: only relatives and close friends contribute to the oral history of the iconic comedian. The result is a protective, but hardly whitewashed movie: the lows are acknowledged, while the highs always come with a heartbreaking reminder that Hicks had just entered his prime when he was taken from us.

I sat down with Harlock and Thomas last week to discuss their work, their love of comedy, and their thoughts on where Hicks might've been headed. As an ardent fan of stand-up comedy, this is something I consider frequently. Hicks was turning into more of an activist before he died; he was particularly outraged by the Gulf War and the Waco siege. According to Harlock, Hicks was being considered for the hosting gig on Comedy Central's POLITICALLY INCORRECT (which ultimately made Bill Maher a household name). National recognition awaited. But would Hicks have kowtowed to the network censors, or would he have taken to the internet and fought the power from his own forum. I hate that we'll never know.

(l. to r. Paul Thomas, Matt Harlock)

Mr. Beaks: What was your gateway drug into stand-up comedy?

Matt Harlock: The first person I was into was Steve Martin, when he was doing his big stadium shows. He was able to command such a large audience, and seemingly still keep it intimate. He was so whimsical and silly, it was a nice thing because the comedy scene in the U.K... when The Comedy Store started in London, it was very political and like, "What's wrong with this country?" There was a TV show called FRIDAY NIGHT LIVE with a comic called Ben Elton, who became very popular and a lot of his stuff was political. Steve Martin was a real change from that. It was something that opened you up to what the possibilities of stand-up were.

Paul Thomas: When I was young, my dad was a huge Woody Allen fan. That was my first exposure. But then there were things like THE JERK with Steve Martin. And then Eddie Murphy's first few live shows blew everyone away - and he was just twenty-one at that stage, I think. I worked in TV comedy after that, and my role there was to find the next raft of new comedians over in the U.K. But things were very different compared to the States. There was a new channel called Channel 4, and part of its remit was to find both new comedy and provocative new formats, and to put provocative ideas onscreen. Every year, there would be twenty or thirty new comics, and the best of them would survive that.

Beaks: How different is it in the U.K. when it comes to honing your sensibility and material in clubs?

Thomas: What we know about American clubs is kind of hearsay. In the British clubs, the audience goes there to see comedy; the lights are down, and everybody's paying attention. What we hear about American clubs is that people are eating food, and the comic is someone who's on in the corner; they're fighting against lots of different things. British audiences are a lot more attentive; they've gone there to watch comedy.

Harlock: The other big difference with London is that, as we understand it, it's got the most comedy clubs per capita of any city. I think there's something like 180 or 220 clubs in London. As stand-ups, we've worked with quite a few comics in the U.K. They say London is one of those places where it's possible to have a career and stay in the same city; that way, you can have a semblance of a normal life. In the U.S., every city has maybe two or three major clubs, and comics spend their time on the road. That's one of the things that's kind of clear about Bill's story: he had to travel, and he had to be on his own. Those are the sacrifices you make as a comedian - if you're going to ply your trade in that way. I think that's one of the things that comes out in the film: how hard it is to be a stand-up if you want to do it properly; how much commitment you need. You really have to be doing it for a proper reason. If you're doing it just to get a sitcom or to be an actor, then maybe that commitment is going to be hard to apply to a career which involves being on your own and traveling all the time.

Beaks: When were you first exposed to Bill Hicks, and what was your reaction?

Harlock: As you know, Bill is someone who has quite a big reputation in the U.K. I wouldn't say he's a household name, but he's certainly moved beyond cult performer. One of the reasons for that is, as Paul was saying, Channel 4 had a remit in the late '80s and early '90s to transmit provocative comedy. We were lucky enough that a British TV crew was at Just For Laughs in Montreal in '91, and saw Bill's one-man show. They filmed it thinking they were going to use ten-minute segments, and ended up convincing Channel 4 to broadcast the whole set - and when that set was broadcast in December of 1991, it really caused a bit of a shockwave throughout the U.K. That was when I first came across him. I was a student at the time, and like many students I was looking for new things. He was one of those guys who really went viral before the internet; people were passing around bootleg... VHS tapes. That actually takes you real time, copying tapes to make for someone, and they really were passed around quite fervently.

So he was someone who crashed into the U.K. comedy scene and really caused a big noise. Previous to that, six months before that broadcast, he had won the Critics' Prize at the Edinburgh Festival. So there was quite a lot of noise around Bill. A lot of people fell in love with him, and expected him to be around for a very long time. The shows the following year were sold out across the U.K. He really entered the public consciousness then.

Thomas: Interestingly, Channel 4 are no longer like that. Now they're chasing ratings. So that kind of dangerous comedian wouldn't appear these days. Bill now shows on the cable satellite channels, like Paramount. Things have changed. In those days, Channel 4 were young and fresh, and the test of whether their shows were good or not were the critical review. Now it's shifted, and they chase ratings - and you don't take risks if when you chase ratings.

Beaks: How did you get in contact with the Hicks family? They've been so protective of his legacy.

Thomas: They were approached a lot over the years, but Matt first made contact.

Harlock: They were weary - and had been for some time - just because they got so many approaches which were blatantly commercial. "Why don't you give us all of your material, and we'll make lots of money on a DVD?" I think they were looking for something that had a quality-control aspect to it. So we were very lucky. I was a filmmaker, but on the side I put on some tribute nights to Bill in the U.K. On the tenth anniversary of his death, we made a little documentary about two or three of those evenings - which were really popular and sold out. We had comedians and rare clips. From that, we got in touch with Bill's family, sent them the material, and said, "This is what's been going on in London. We just wanted you to know." From those conversations, we kind of realized that not only was there lots of Bill material - which we had been peripherally aware of, but maybe hadn't thought about that much before - but also realized that Bill's story had never really been told in a complete and full way. There had been one documentary made in the U.K. the year that he died, which was short, about forty minutes for TV. But other than that, there hadn't been anything else. So we got in contact with the knowledge of the material existing. It was a two-year conversation to get to the point where they trusted us and, through Paul's TV background, engineer a U.K. broadcast commission with the BBC.

Thomas: The family were looking for that more substantial approach as well. They had been approached by people basically wanting clips, but they had been waiting for something on a higher level that did try to tell Bill's story as well. So the fact that there was a U.K. broadcaster involved, that confirmed to the family that the project was going to be a certain caliber. But even then it was a leap into the unknown for them, and it was only when it was finished that they knew they made the right choice.

Once the family committed, then there was this ripple effect where [Bill's mother] Mary called a few of the other people and said, "This is the one. We're doing this." And Dwight [Slade, Bill's first comedy partner]. He's such a key part of the childhood story, but he wasn't keen to take part in the early going. Then Mary sort of persuaded him, and once he was aboard, it was fine and the story just poured out. Dwight's so pivotal to establishing that sense of who Bill is in the early part of the film.

Beaks: I don't know if you'd have a movie without him. So was the animation technique a tipping point for them?

Thomas: That came from a lot of other places. We knew that broadcasters were being pitched this regularly, and we knew that we needed something that would pique their interest. Documentaries had been moving down this more narrative route; you'd had TOUCHING THE VOID and THE KID STAYS IN THE PICTURE, where you're not looking at talking heads but taking the audience into that world. We knew we wanted to go down that route, and we did some early tests with photographs. But it was really when we did the interviews, and we spoke to these ten people who knew Bill... that's when the story just ballooned in terms of how much they still remembered, and how strong a sense of Bill they all conveyed. We came back from that knowing we had a big job on our hands, and the animation then had to grow to match that.

I guess the early scene where they're sneaking out [of their houses]... up to that point in the film, you're still seeing photographs. But that's an action sequence; we had to convey what it's like for a set of teenagers to disobey their parents and go down to an adult nightclub in Houston. That was the big test for us. We did a couple of early passes, and it started to feel filmic quite quickly with the vehicles moving. THE KID STAYS IN THE PICTURE used a similar thing, but it was much more of a slideshow with photographs - whereas ours is much more in the round, where you're cutting and doing a reverse shot with a wide, and you're moving. It just feels much more filmic - and the audience is in there being transported through that world.

Harlock: There were two things important about the technique: you were allowed to do things that recreate moments and time-and-place. If you'd done a film which started from now and went until 2020, all of the digital photographs would look the same. But when you're looking at period Polaroids from the 1960s and '70s, those really create a sense of time and place. The other really important thing is that Bill is back in the story now; if you'd had a talking heads and clips documentary, which I think a lot of people would've expected, then you'd be looking at a film where Bill is conspicuous by his absence. Yes, he'd be on stage, but he wouldn't be part of that story. What the voices do is tell this wonderful set of scenes and narrative moments, where Bill is actually there in the same world as them, and you feel like he's part of that. The other thing we were careful about was that we wanted to make sure we handled the animation with as much veracity as we could. So, for example, in the speaking-out scene, that's actually Bill's real childhood home. We went back and found the real location - so the annex where [Bill and Dwight] started their comedy, that's recreated from period photographs at the time. We were quite keen to use real locations whenever we could, and we went back and found those from that point in Bill's life.

Thomas: When the Houston comics saw [the film] last year, they said we'd really caught the atmosphere of that place. That was put together from a handful of surviving photographs.

Beaks: It was thrilling to see Bill's early live performances. As fans, you must've been overwhelmed getting to sift through this material.

Thomas: Putting it together in order was the first amazing moment, where you then see Bill's comedy developing, and him growing and changing so much throughout his career.

Beaks: Was there any great material that you had trouble cutting out of the film?

Thomas: There was loads. Some, the audio quality's not good enough. He was doing a lot of amazing material early on, but one of the jobs of the story is you have to see his comedy develop and move on, so you kind of have to hold it back and parse it quite carefully. But there's an lot of amazingly bold and brilliant material from when he's still very young.

Harlock: The other thing was that you have to make sure when you're showing performances that they actually fit into what's going on in his life at the time. So it wasn't just a question of trying to find the best Bill clips that we'd like to see and then trying to make the story fit around that; it was really about the interviewees and their telling of the story. You want to know that Bill's just got clean and sober, and has had six months of a shitty time in New York not being able to be funny, and then you come back into the performance where he's able to nail it again. That's really important, that biographically you understand where he is at the time before you see each of the performances. That's kind of the way that the film works; the [performances] are woven together with the real-life aspects that were going on with him.

Thomas: And even the clips are cut as well. So when he arrives at SANE MAN, the first bit where he says he's back in Austin is several minutes before the bit he goes into. So there's a lot of compressing going on. Those clips also reveal who Bill is as well; it's not just the comedy you're seeing, but him, the real person involved.

Beaks: People always wonder what Bill would be doing today if he were alive. I don't know if he would've gone for something like THE DAILY SHOW. Satire might've taken the edge off of his comedy.

Harlock: As we understand it, Bill was actually up for Bill Maher's job on POLITICALLY INCORRECT, which was 1993. I think the thing that drove Bill was to get his message out to audiences, and obviously he had trouble doing that via the mechanism of television. Network TV, particularly in the States, was very restrictive, with the five minutes of clean [material] that was required. That really wasn't the way Bill worked in terms of engaging audiences. I think the changes that have occurred since Bill was alive... you know, he heard the first whispers of this thing called "the internet" while he was alive. Now every single person can be their own broadcasting station; they can have their own TV channel on YouTube, and they can put out whatever they want. I think one of the things Bill might've been interested in doing was being able to broadcast to as many people as were interested in listening to him unfettered by the TV standards and practices. He would be able to broadcast and connect with audiences in whatever way he wanted. I mean, I think it's nice to think he might've been on TV and finding audiences; maybe some TV network or executive might've said, "Look, this guy's got something to say." And in the fifteen years since he's been around, things like THE DAILY SHOW and THE COLBERT REPORT have shown there's an audience for that.

But at the same time, you're right. Maybe he would've said, "Nope! Can't have any controls at all." Who knows? Maybe he would've been sitting on an island sipping water and writing weird novels. It's just one of those things that you can't ever know. But I think he would've been doing what he was attempting to do throughout his life, which is to reach audiences with his message that you can think for yourself and don't have to believe what you're told by the media - and that there are more beautiful and wonderful things in this world than you find on your TV set.

Beaks: It just feels that, with his outrage over the Waco siege, he was maybe heading in more of an activist direction. Do you think he might've segued out of comedy? And can you think of any comics who are challenging the establishment as actively and belligerently as he did?

Thomas: He was incessantly interested in everything that was happening around him - both on a small scale and on a world scale. So it's hard to imagine that he wouldn't have cared to develop his own particular viewpoint on things - especially the way history is repeating so frequently. I think he would've had a lot to say on that. In terms of other comedians doing the same thing... I love Doug Stanhope. I think he's fantastic, but he's got a more nihilistic approach. Bill had hope and a belief that there is a way out of all of this. In terms of challenging the establishment, Michael Moore is doing it in the documentary form. Financiers realize there is money to be made, that there is an audience for this kind of stuff. THE DAILY SHOW is operating under certain rules. I think Howard Stern is interesting, in that he has taken a route so that can say exactly what he likes. Bill probably would've gravitated towards an area where he had total freedom. But there's no one else remotely like him at the moment.

Harlock: Someone was talking about what the basic ingredients for a stand-up comedian are. There's a phrase that you guys have in baseball. Is it "five-tool"?

Beaks: A "five-tool player".

Harlock: There was a guy talking about Peter Cook. He was saying, "Peter Cook had it all! He could clown, he was surreal, and he was a satirist." Normally, comedians tend to have one or other of those things. But Bill also had, in addition to those things, a wonderful physicality about him. He was really good at falling over. I don't know if you've ever seen Bill fall over, but it's a sight to see. He studied physical comedians. He was really into Chaplin and Keaton. He was also very much about creating soundscapes and scenes. People described his shows as very theatrical. He was able to do that, but he was also a real student of the craft - and that means joke-writing. Even though you're going to go off on political subject matter where you don't have a joke for fifteen minutes, you can still bring it around with that twist at the end. So even though Bill later in his career became very political and was very outraged by certain things that the government were doing, he also never lost sight that the way to reach audience is by taking an idea and turning it on its head. That kind of craft, that ability to see what the overriding scope of a joke is and how to get an audience to do that mind-flip where it really hits home is something that he never lost. So "five-tool player"? I'd say Bill was the "five-tool player" of comics.

After we ended the interview, Harlock gave me one of the laminated cards handed out to guests at Hicks's funeral. On it is inscribed the comedian's final message to the world: "I left in love, in laughter, and in truth. And wherever truth, love and laughter abide, I am there in spirit."

AMERICAN: THE BILL HICKS STORY is currently playing in New York City and Los Angeles. It expands this Friday, April 22nd.

Faithfully submitted,