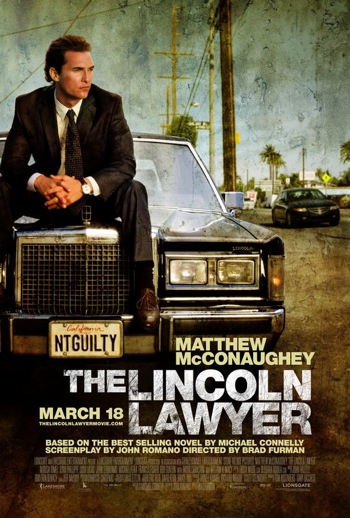

THE LINCOLN LAWYER is a confidently constructed, effortlessly entertaining legal thriller the likes of Hollywood rarely makes anymore. Based on the bestselling novel by Michael Connelly, it stars Matthew McConaughey as a drawlingly charismatic criminal defense attorney attempting to clear a rich-kid client of brutally assaulting a young woman. It's a simple premise told in a relatively familiar fashion, but it's constantly elevated by a top-notch cast, some very smart writing and proficient direction from rising young filmmaker Brad Furman.

Right from the opening moments, which finds the camera casually following the laid-back McConaughey wherever he saunters, it's clear that Furman's more than just a point-and-shoot guy (i.e. the type of director typically assigned to material like this). Though THE LINCOLN LAWYER is only his second film (the first being the indie crime flick THE TAKE), he's already comfortable with long - but never ostentatious - takes, and pays close attention to character detail. Every player in this drama is a type of some sort, but they've all got amusing little quirks that humanize them in unexpected ways. It helps, obviously, that these characters have been brought to idiosyncratic life by folks like William H. Macy, Marisa Tomei, Michael Pena, John Leguizamo, Bryan Cranston, Frances Fisher, Bob Gunton, Shea Whigham and so on, but they've clearly been inspired to bring their "A" game. And one can only conclude that this is Furman's doing.

Before interviewing Furman a couple of weeks ago, I talked to Michael Paré, who plays a veteran detective looking to burn McConaughey's hotshot attorney. When I told the actor I'd be talking to Furman later that day, he immediately began praising the young director, and shared this story from the production which illustrates why he may very well be a filmmaker to watch:

I gotta tell you, there's this one shot in the movie that's really critical. It involved, like, five different camera focus marks. And if it didn't work, then the scene wouldn't work. Brad choreographed this whole shot, then brought in his DP, and got it in five takes. When I did ADR for it, we were sitting there. and he says, "Yeah, I got lucky." And I said, "What are you fucking talking about 'lucky', man? You worked so hard to prepare that shot, and you knew exactly and at what syllable the focus had to change. And you said you just got 'lucky'?"

I think he's going to be a fucking giant. He does it, but acts very humble about it. He works twenty hours a day. He's modest, but obsessive. He's specific. And he doesn't stop until he has what he wants. And he plays basketball, and he's into jazz, and he's from Philadelphia!

So sayeth Michael Paré, so it must be.

Mr. Beaks: According to Michael Connelly, Tommy Lee Jones was attached to direct at one time.

Brad Furman: Yeah, he was going to direct and play the Bill Macy role.

Beaks: So when did you come in?

Furman: At some point he fell out. They had been searching for a director for quite some time. I got put in touch with Matthew for his passion project called BONE GAME, which is this gritty rodeo movie - sort of like THE WRESTLER. I loved that script; I thought he was perfect to play it. I went to meet him and pitch him on why I thought I'd be the perfect director for BONE GAME, and we really hit it off; he really thought I was right for BONE GAME. But as with most of these situations, the reality is... you know, is the actor going to make it or not, and if so, when? So I was like, "If you're interested, when are you going to do it?" And he's like, "I don't know. I'll let you know." And then two weeks later, I got a call from my agent, and he said, "You're going in tomorrow to meet for THE LINCOLN LAWYER. Matthew put you up for it." I was so confused. I was like, "What happened to BONE GAME?" And he said, "Matthew decided he wants to make THE LINCOLN LAWYER next." I was like, "Am I the only guy going in?" I was really confused.

[Producer] Tom Rosenberg loves to tell me that there wasn't a chance in hell he was ever hiring me for this movie. Then I met him, and I guess I won him over. It was just one of those things.

Beaks: Had you read any Michael Connelly books before meeting on THE LINCOLN LAWYER?

Furman: Yeah, but I had not read this book. I had an awareness. I mostly grew up with John Grisham, and [Connelly] is sort of the new version of that. Regardless, I got the script, and six hours later I was in the room. (Laughs) I didn't get that script until late that night [before the meeting].

Beaks: Was it your kind of material?

Furman: It was in the sense of making a drama, fleshing out the characters, and making each character be a human being and have them be three dimensional. Both of my parents were attorneys, and my grandfather was an attorney. I'd been in a courtroom since I was ten years old, when I started working for my grandfather as a runner for his law firm; I used to go down and check out the courtrooms, and I was obsessed with all of the criminal stuff in Philadelphia. I felt like I knew how to make the movie. Plus, all the schlock that had been sent to me... the type of movies we're making today are so poor, and I felt like this was the type of movie that would never get made in today's Hollywood. And Rosenberg felt like there was a market for this movie. He felt like this was the kind of movie he'd want to see, and, as a result, he was like, "I'm going to make this movie." That set the bar right there. Nobody else would've made this movie, and that felt very exciting for me.

Look, ideally, I've written movies. I've got tons of movies running through my head, things I'm dying to make. Probably if I was making those I'd be freaking out; those have been in my head for ten years. Next best thing, I don't think I could've asked for more. This was great.

Beaks: You mentioned getting "schlocky" scripts. When you're only one foot up on the rung, you generally don't see the "good" stuff, right?

Furman: You don't see any of that. On top of that, your job always is to elevate the material and make it better. That's the situation: you get a really shitty script with a good idea, and you've got to take it and make it better. That was my agent's big pitch to me all the time: "You're not going to get a good script. Good scripts? They're going to Tony Scott, Ridley Scott and Martin Scorsese. You're going to get what you're going to get." And most of those scripts you're getting aren't even financed. Then there's the studio ones that are, and everything studio today is pretty much genre or really big. It's a tough game. Studios just aren't making as many films as they used to.

Beaks: Twenty years ago, the studios would churn out at least ten thrillers a year roughly in the vein of THE LINCOLN LAWYER. Maybe two of them would be good, but most of them would turn a profit.

Furman: If this performs, maybe they'll start doing that again. I don't know.

Beaks: You talked about fleshing out the characters in THE LINCOLN LAWYER. That's one of the things that immediately popped for me. There's a lot of fine detail, little touches, like William H. Macy's house. There's the slight untidiness, the small piles of books on the staircase, that humanizes him. There's a lot of stuff like this. How much do you think about these details?

Furman: I'm fanatical about detail. I lose my mind. I probably just make everybody around me crazy, but hopefully in a good way. Whether it's making the world a character, or making sure the world in which the characters are living is real, that's crucial. A lot of that comes from collaborating with the right people. And it comes from the actors' ideas. On my first film [THE TAKE], Bobby Cannavale and I had a lot of conversations about how his character hadn't slept in days; he had nine open cases, and he was constantly drinking coffee to stay awake. There's a scene where we shot a steadicam thing where the cup is in his mouth - he brought that. That was his thing, but it came out of former conversations that we had.

It was very similar on THE LINCOLN LAWYER. With Bryan Cranston's look, we had conversations where he said, "This is what I think we should do." And I was like, "Boom. Got it." The same thing happened with Michael Pena. We shot his scenes chronologically, and somehow he chipped his tooth prior to the prison scene. He was calling me, saying, "Dude, I chipped my tooth! What am I going to do?" And I was like, "Are you kidding me? Leave it. That's awesome. You're in prison, and you have a chipped tooth now!" It's really subtle. I don't think you're going to look at him and go, "His tooth is chipped," but he looks different. The chipped tooth changes his face a little. It's interesting, and it works. So there are those happy accidents mixed with really thinking and being specific with how you do things. And there's how you communicate to the crew, and how that executes itself. I leave no stone unturned. I'm just built that way.

Beaks: There's a really great tracking shot in THE LINCOLN LAWYER - and it's great partially because I didn't recognize it was a tracking shot until after you cut. But it's nice because it immerses us in Mick's day-to-day courthouse life. It reminded me of the squad house scene near the beginning of 48 HRS. How difficult was that to pull off?

Furman: From what I've been told, a movie like this would typically be a sixty-day shoot. This was a forty-day shoot. It was pretty tight, I think, for a 130-page script. It's big, and there are a lot of moving pieces. But I shoot from my gut. I really believe substance is everything. I think we're living in a world today where style is over substance. I believe the style should elevate the substance. As a result, I'm shooting from my gut in that I'm making decisions stylistically that hopefully elevate the substance of the movie and the core of what the experience is - and, obviously, have them married together in a way that is seamless. You don't ever want to be watching a movie and see the camera; that's a pretty poor error in filmmaking from my perspective.

I break down the script. I see it in my head, play with it, and challenge myself. Then my cinematographer [Lukas Ettlin] challenges me - and vice-versa - and the two of us hammer it out together. We have a real symbiotic relationship, this way of speaking without speaking that I think really works on set. Things change, you know? Filmmaking... that's what's so fun about it, but that's what's also challenging about it: you're dealing with all of these real-life circumstances you're trying to capture, and yet have it not feel awkward or stilted. Have it feel natural to the environment that you're in, and, actually, natural to the camera itself so that as you capture it it has this natural feel to it. I don't know... (Laughs) it's hard to quantify it.

Beaks: So I interviewed Michael Paré this morning.

Furman; Oh, yeah?

Beaks: I had to, man. He was in a couple of films and TV shows that had a huge impact on my childhood.

Furman: Dude, he's amazing.

Beaks: He was talking about that rather impressive shot you pull off in the courtroom, and how you were so humble once you nailed it. He said you acted like you got lucky with the shot when you clearly had it meticulously thought out the whole way through.

Furman: (Laughs) I know what he's talking about. There's that big reveal in the courtroom, and... I still feel like we got lucky. (Laughs) Michael seems to think I knew what I was doing, but who knows. That's definitely a moment I'm proud of, though. I knew if that moment didn't work, the movie wouldn't work.

Beaks: In any event, it's great to see Paré playing a badass older detective. It feels like this could be the beginning of a really good run for him. And there are lots of great little performances like this in the movie, guys like Shea Whigham, Michael Pena, Margarita Levieva... were these people you were eager to work with all along?

Furman: I saw Shea in ALL THE REAL GIRLS, and ever since then I've been obsessed with him. It's so crazy. I was flirting with a Bret Easton Ellis project, and had tried to get Shea to play the Cannavale role in THE TAKE. In a small movie like that, you don't know who's going to do your movie. It's complicated. I'd reached out to Shea, and never really got that far with him. I mean, I was thrilled when I got Bobby, but I had been really obsessed with Shea. I just knew I really wanted to work with him, so when I got this chance I just went for it. The reason that I was able to get him on this movie... I mean, yeah, it was a bigger movie, so I guess you could get to him. But I had used that Easton Ellis movie - after I found out his brother was an agent at CAA - to get a general with him. And when I got in the room with him, I was like, "Listen, dude, I am obsessed with you. I don't mean to be weird, but you are amazing."

And Michael... I loved EDDIE AND THE CRUISERS. I still love that movie. So the thought of bringing him back was just huge, and Rosenberg was really supportive. And Margarita Levieva... I saw her in ADVENTURELAND. We were really having trouble finding Reggie Campo, and I was like, "That girl is awesome. She's a movie star. She's got something special." They didn't think she'd come in; they thought it was too small of a role for her.

Beaks: Which directors have influenced you most as you've learned your craft?

Furman: As far as enjoyment purposes, Spielberg for sure. I just enjoy his movies so much. But really, one in particular in American cinema would be Scorsese. That's probably the most commonly mentioned name, but there's something about his early work in particular. When you look at the world of TAXI DRIVER, RAGING BULL or MEAN STREETS, and the way these characters interact and how real they feel and the execution of it... even in MEAN STREETS, the opening 16mm... there's just some really special stuff that was brimming with enthusiasm and excitement.

Definitely THE FRENCH CONNECTION, and Friedkin's execution of that. Everything was on the fly; it was a lot of run-and-gun and just getting it in the can. As with anything, it's confidence. You're always doubting yourself early in the journey, and it gave me confidence to know that there's no set of rules. I feel like living in the world of Hollywood and working in it, it's like "This is how you make a movie. 'The 10 Rules to Making a Movie.' You exist in this box." And I'm like, "That's not it at all!" There are no rules to this game. You can make them up as you go - and you can bend them and you can break them. I know that's made me controversial in certain ways, but that's truly what I believe. I'm not formally trained as a filmmaker. I was taught by my dear friend and cinematographer, who was doing this from the age of five, whereas I didn't pick up a camera until I was nineteen or twenty. I think inherently I'm trying to break new ground, but not even doing it purposefully. I'm just going by my gut and not worrying about what I should be doing or what the rules are.

Beaks: So is there a game plan? Do you know where you want to go after THE LINCOLN LAWYER? Is there a type of film you want to make?

Furman: If you look at Sidney Lumet's career or Scorsese or Friedkin... the reality is that these guys are seminal filmmakers. When I was younger, I would say, "Oh, I want to be the next Martin Scorsese." I don't say that anymore. I'm just really focused on being me - whatever that means. So taking part A of that question and applying it to Part B, I'm just trying to make what I hope to be are great films that, forty or fifty years from now, people can still watch and still talk about. And hopefully start to make films that have a message, be it social or political. Just have a voice. Like Darren Aronofsky. Whether you like BLACK SWAN or not, he's got a voice. He's got a perspective, a vision. To date, he's done what he wants to do.

THE LINCOLN LAWYER opens wide on March 18th, and is easily one of the most entertaining movies I've seen this year. If you miss smart adult thrillers with great grown-up casts, I highly recommend it.

Faithfully submitted,