Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

"Even a child can tell you that something that's still alive after being buried thousands... no tens of thousands of years is dangerous."

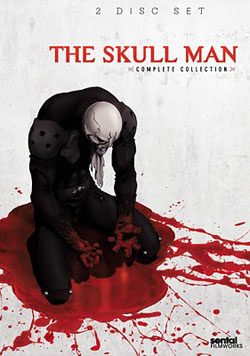

Anime Spotlight: The Skull Man – The Complete Collection Released by Section 23

I recently felt like taking a break and dealing with something that didn't feel too much like the bulk of other anime/manga. Having recently watched Skull Man, it occurred to me that the 13 episode anime series fit the bill. Even though many mature audience anime works do have their own identities (there aren't that many produced in the first place, and those that are tend to be either from boundary pushing studios like Madhouse or Studio4C or counter-programming blocks like Noitamina), the impression that Skull Man was unlike the other anime that I inundate myself with was curious considering that it features numerous characteristics associated with anime of the 90's and early 00's and that it was based on the work of Shotaro Ishinomori, one of the defining figures of anime and manga. Yet, in the slow burn tragedy, strategically interwoven with plenty of un-self-consciously used genre trapping, anime industry fixture Takeshi Mori (Otaku no Video, Giant Robo, story boards on Ranma ½, Ruruoni Kenshin and Eureka Seven) and studio Bones (Cowboy Bebop: Knockin on Heavens Door, Sword of the Stranger, Fullmetal Alchemist) put together an anime that stands out as smartly constructed and conceived. At once, Skull Man is one of the most restrained and one of the most excessive anime I've seen in a while. An early episode has the titular phantom antihero along with his three eyed doberman-man and lion-woman compatriots executing an apparently harmless bird woman. Yet, without doing a bait and switch, it proceeds to get itself lost in the tall grass of a Japanese flavored Berlin meets Innsmouth city. With the Skull Man himself relegated to one of a number of disquieting features of the landscape, a myriad of dark, personal endeavors, revenge, family ties and ambition play themselves out over the anime 13 episodes. With remarkable sophistication, the anime establishes its own time and place in which these agendas can entangle themselves. To my mind, great anime is defined by characters that draw the viewer's empathy and a presentation that offers a new experience. As mystifying as bits of Skull Man are, it’s often Shakespearian web of characters does often resonate. And, while it's not one of anime's most visually grant endeavors, the cloaks and daggers, motorcycle mounted masked men, cyborgs and mutants grand guignol is bound to excite any genre fan.Debuting in 1970, Ishonomori's original, one volume Skull Man manga predated Go Nagai's more famous horror superhero Devilman (1972) or Devilman's precursor Mao Dante (1971). The lead was a masked phantom, looking like a dark mirror of many of the heroes Ishinomori developed. In his introduction, Skull Man's transforming werewolf/bat/alligator Garo causes a train derailment before the lead assaults a group of techs as a precursor to blowing up their lab. (Anime World Order/Otaku USA's Daryl Surat recently noted that Skull Man destroys plans for the "3D TV" citing "idiots will fight each other to get theirs first, just like the color TV"). Other action in the volume includes Skull Man and his shifting assistant killing couples during their odd trysts into a swamp and blowing up Boeing jet before revealing their convoluted personal vendetta against a powerful man and the many tendrils of the war industry. A second Skull Man manga was produced by Kazuhiko Shimamoto in 1998 using notes provided by Ishinomori before his death that year. In the North American market, the title had the distinction of being one of the early releases in Tokyopop's $10, unflipped "Authentic Manga" line. There was then a third Skull Man manga in 2007, by MEIMU (who also produced an adaptation of Ishinomori’s Kikaider, released in North America by CMX). When the maestro of bombastic mecha anime Yasuhiro Imagawa revived the forefather of the genre, Tetsujin 28, in a 2004 anime series, Imagawa put together a worked informed by the social/political issues that informed the creation of the original. That Tetsujin 28 series was set during Japan's post war reconstruction. Inescapably around the boy detective and his weapon turned robot surrogate, industry was picking up, but many people were still living desperate live, and that technologically driven future represented as much looming threat as it did possibility. The original Skull Man owed more to Ishinomori’s attitudes about the cold-war engaged globe than it did specific situations. Other of his manga were more directly entrenched in the events, as can be seen in the North American released 2006 anime adaptation of Ishonomori's cyborg spy 009-1 (the name of which is a pun of kunoichi or ninja woman), set in a fictionalized version of Germany still divided after a century of international tensions. In that case, the anime provided a sort of engagingly extravagant European spy versus spy with cyborgs and ray guns. Bones 2007 Skull Man retrofits that tension into the subject, with a series set in a divided (across the Tsugaru Strait, also seen in The Place Promised in Our Early Days), semi-fascist Japan, rebuilding after several referenced Asian wars. Larger powers are keeping an eye on the archipelago. Check points and curfews are in place. The military and police are empowered with great leeway in enforcing order. An early scene of the anime shows the military shooting a man trying to cross a border without the proper paperwork. Despite all the geo-political business going on in Skull Man's world, its story zeros in on Otomo City, site of a powerful pharmaceutical company. About a decade ago, it was a smaller community centered around the Kagura clan. Then, arson killed the head of the family along with his son Tatsuo (name of Skull Man in the earlier manga). Now the Kagura are buried, with the site of their former community under a dam flooded reservoir. Taking its place, there is a city enjoying an authoritarian muted prosperity under the control of the Otomo corporation, a corrupt police department and, seemingly a growing religious cult known as the White Bell Society. Into that environment comes Skull Man, a mystery villain, killing without apparent pattern in the depth of the curfew quieted night. In the first episode, a train arrives at Otomo, bringing hack journalist Hayato Mikogami returning from Tokyo to his home town to ferret out the reality behind the Skull Man rumors, Kiriko Mamiya: a 16 year old tomboy photographer with poorly forged paperwork, Kyoichiro Tachigi: an old, gruff PI who seems to know a bit about everything, actress Yui Onizuka and her assistant Sayoko Karasuma. Needless to say, these folks aren't destined for happy rendezvous with Skull Man. Shotaro Ishinomori is a name that isn't especially familiar in North America outside enthusiasts of Japanese media, but we have seen plenty of his works, and even more of his impact. Recognized by Guinness as the world's most prolific comic creator (credited with over 128,000 pages), Ishinomori's works included shoujo, economic guide Japan Inc, Hotel, tales of the works of a first class hotel that published in the adult audience Big Comic or period pieces like warrant executers mysteries Sabu to Ichi Torimono Hikae and bamboo worker/debt collector Sandarabotchi, but he's probably best remembered for his heroes. Ishinomori grew up with a wave of children who felt the impact of Osamu Tezuka's New Treasure Island. There has been modern debate concerning the extent to which Tezuka truly revolutionized the story telling structure of manga through New Treasure Island, but it's influence on the commercial and artistic currents of the medium are undeniable. The aspiring novelist Ishinomori would find work as Osamu Tezuka's assistant, and was one of the artists destined to be legends in their own rights who took up residence in Tezuka's run down Tokiwaso apartment building. In 1964, Ishinomori created what could be thought of as Japan's X-Men, Cyborg 009 (published in North America by Tokyopop. A 2001 anime adaptation aired on Cartoon Network, 8 episodes of which were released on DVD). A group of international people (often very stereotypical - a psychic Russian baby named Ivan Whisky, a New Yorker ripped from West Side Story named Jet Link, a French ballet dancer named Françoise Arnoul, gruff German Albert Heinrich, silent Native American Geronimo Jr., ground Chinese cook Chang Changku, English James Bond figure Great Britain, African slave Pyunma, and the primary hero, half Japanese orphan Jo Shimamura) were kidnapped by the international arms development/dealing secret organization Black Ghost, subjected to military testing and turned into experimental cyborgs. With the help of defector Dr. Isaac Gilmore, the group would run from and when possibly thwart the efforts of Black Ghost. Ishinomori, who has been described as a pacifist would used these often pulpy, often outlandish fights against robots, Greek gods, Edgar Rice Burroughsian civilizations and the like to speak to real issues, such as the war in Vietnam, as well as a broader ideas about war-making. These themes would be reused when Ishinomori developed the Kamen Rider series. Tokusatsu (special effects) heroes made their debut on Japanese TV in 1958 with Kawauchi Kohan's masked vigilante Moonlight Mask. Despite its popularity, Moonlight Mask met an unceremonious end in July 1959, when the series was cancelled due to liability issues concerning children imitating Moonlight Mask's stunts. In the mid 60's Toru Hirayama began working to develop a TV adventure starring a masked hero. By the end of the decade, he approached Shotaro Ishinomori and considered basing his show on Ishinomori's vengeance driven anti hero-Skull Man, but ultimately opted against using the violent spirit of Ishinomori's manga. By 1971 Ishinomori had reworked the premise. Rather than a skull, his hero would have the face of a different object of boys' fascination, a bug, specifically a grasshopper. And like the heroes of Cyborg 009, this kamen ("masked") motorcyclist hero was alone in a battle against the sinister architect of his creation. In this case, biochemistry student Takeshi Hongo was able to escape the evil organization known as Shocker's attempt to turn him into a cyborg agent. Freed before his will and conscience were scheduled to be removed, Hongo turns his ability to undergo a heshin (transformation) into the super powered Kamen Rider 1 against his would-be masters. (20 Kamen Rider TV series have been produced. Generation Kikaida has released Kamen Rider V3 in North America. Tokyo Shock released the remake movie Masked Rider The First and Kamen Rider The Next. Saban attempted a Masked Rider localization and more recently, Kamen Rider: Dragon Knight was adapted from 2002's Kamen Rider Ryuki) Ishinomori's ideology and impact on tokusatsu would continue with biochromatic sci-fi hippy Kikaider. The jinzo ningen/artificial human serving as the subject is Jiro. Created in the DARK labs of the demonic Professor Gill, Dr. Komyoji creates an android governed by an incomplete conscience circuit. Komyoji's Pinocchio, Jiro escapes Professor Gill's lab with the mission of protecting Komyoji's son and daughter, as well as thwarting Gill. As Jiro, actor Ban Daisuke (Dr. Ikuma in the Ring movies) plays a young, denim clad man, travelling the lonely roads on his yellow motorcycle, red guitar strapped to his back. But, when the hordes of naginata-spear wielding DARK androids and ferocious Destructoids, from Blue Buffalo and Red Condor to Carmine Spider and Green Sponge, attack, Jiro yells "Change! Switch on! 1-2-3!!," where upon his body metamorphoses into the bichromatic Kikaida, a half blue, half red robot with the asymmetry emphasized by a circuit shell protruding out of the red side of his face. Beyond Kikaider's enduring popularity, it served to inspire one of the branches of the tokusatsu tree, the Metal Heroes - Begun in 1982 with Uchuu Keiji Gavan, these metal, transforming law enforcement officers have included the sources for Big Bad Beetleborgs (Juukou B-Fighter) and VR Troopers (Metalder, Spielvan and Shaider). (Generation Kikaida released Kikaida and its follow-up Kikaider 01. Bandai Entertainment release the Kikaider TV anime, which also aired on Cartoon Network, and follow-up OVA Kikaider 01, but not The Boy Who Carried a Guitar: Kikaider Vs. Inazuman. Spin-off movie Mechanical Violator Hakaider was released by Tokyo Shock) And, in 1975, the Toei and Bandai produced stories of mecha equipped "task forces" Super Sentai began with Shotaro Ishinomori created Himitsu Sentai Goranger (Secret Squadron Five Rangers), which would become the basis for the Power Rangers franchise. To evoke the standard bearer of mecha excess again, when Imagawa oversaw a Giant Robo OVA, he pulled in copious amounts of creator Mitsuteru Yokoyama's other works from the adaptations of Chinese classic The Water Margin and Romance of the Three Kingdoms to manga's Bewitched magical girl Witch Sally. Skull Man is a bit quieter in its ambitions to draw from Ishinomori's work. The cold war context for many of his takes on evil done in the pursuit of weapons development is fundamental here. With a scarf separating Skull Man's silver death's head from his leather clad body, this design is doing its best to evoke the look of Ishonomori's Kamen Rider. The veteran investigator Tachigi appears to be doing a verbal equivalent when he refers to himself with the very Kamen Rider phrase "Ally of Justice." Tachigi is also the character who speaks to the psychological underpinnings of something like Skull Man, while one of the antagonists gives similar voice to the adversaries in Ishinomori works. Ultimately, Cyborg 009 is also significant to Skull Man. I'd unreservedly recommend the anime, and yet, its payoff does rest on recognition of Cyborg 009 imagery and appreciation of that title. Skull Man offers a perfect contrast of restraint and excess. It's dark, but not given to the same sort of lashing out that marked the original, young audience oriented manga (it ran in Weekly Shonen Magazine, home of Cyborg 009. GTO, Love Hina, Air Gear). Otomo City is an infernal device, ticking down towards something terrible. The powers that be have their agendas in place and the players arriving on that train have their own objectives. Most of these are at cross currents and most of these are progressing toward tragedy. The mystery is bewildering at times, often because the larger chain of events is not slowed to allow minor interplays to come to fruition. In this anime, the larger gears are allowed to crush the smaller ones. Beyond that, misdirection is well engaged. The anime will set its viewer to look out for one thing, and, while vigilant for that, step in with a fake delivery or red herrings. (Declaring this intention, a fictional film called "False Blindside" crops up throughout) Episodes don't even end on traditional notes. Rather than cliff hangers or resolutions, many just cut out. It's all more confused than a simple a "who's the Skull Man?" mystery. If this were released as it once might have been, across four volumes, it would have been disastrous. Packaged in one it's a fascinating series to follow. It works because of how well drawn the characters are. Beyond giving them defined motivations, the cast is established as able but limited. Kiriko for example is not quite as mature as she'd like to think she was. A such, a viewer can piece together where these people are coming from and what they can do. When you rewatch the anime, the characters and events all fit together with fewer seems than might be expected. In retrospect, it’s event that the anime respected its viewer’s intelligence. The compliment to that denial and obfuscation is Skull Man's willingness to go big. Director Takeshi Mori's resume suggests versatility. Little can be read from his involvement. In this case, it's the writers who offer a clue as to what to expect. Series composer and writer of a quarter of the series Yutaka Izubuchi did well liked, often strange post Evangelion series Rahxephon, which featured a terrific first episode fake-out. That said, Izubuchi is more a designer than he is a writer (he did characters on Record of Lodoss War, the famous Kerbosos armor used in Jin-Roh and the related Oshii works, as well as mecha for the releastic Patlabor, the Black Claw costume on Hideaki Anno's Cutie Honey, design on the Escaflowne movie, mecha on Gasaraki, and a host of design work across a host of Gundam). An episode was written by Shingo Takeba, another designer, whose work includes Rahxephon, Gasaraki, Escaflowne, Wolf's Rain, and recently Heroman. Seishi Minakami wrote a quarter and has some impressive works to the name, including Paprika, Paranoia Agent and Shigurui: Death Frenzy. And, finally, Hiroshi Ohnogi wrote a quarter. I recently detailed Mr Ohnogi's career extensively in a feature on Rin ~Daughters of Mnemosyne~. This is the writer responsible for scripts on Macross designer/co-creator Shoji Kawamori's gobsmacking spiritual works including bird people populated Macross Zero, environmental agitation piece Arjuna and Aquarion - the Getter Robo homage where the teen pilots orgasm as their planes combine. When heading out in the direction, Skull Man doesn't just go out on a limb, it leaps off the tree. In the vein of post-Evangelion, post-Ghost in the Shell anime, it's happy to introduce philosophical or artistic references. What's gonzo here is how literal the anime uses the concepts it evokes. It gets a bit shaky when intertwining Nietzsche, recordings of "The Voice of God," and Wagner, but this crew seems to be stepping into the Nazi danger zone with both eyes open. While there are no shortage of conceits, when the characters orate to these concept, it actually works. The exchanges between nationalists and death merchants, mutants vocally clinging to their humanity, villainous proclamations, for a change, the dialog is sharp enough that it's not just noise. The manifested allusions and the Ishinomori pulp are amplified as the various plans at work in Otomo blossom. A Skull Man says, in order to destroy an evil, you must become an even greater evil. Otomo City, by its identity and foundation is interwoven with the conflict. Well, beyond the crimes of the past, the present corruption, and the authoritarianism, a whole bunch of extra toxic waste left over from the wars is about to be pumped in. As such, Skull Man has a city sized evil, with global tendrils to match. And, in his own fashion, he's up to it. In the final confrontation, he tells an adversary that they talk too much, "true evil is silent." Enough probably are, but on both global and specific scales, not every question raised by the anime will be answered to every viewer's satisfaction. Yet, even if you can't catch the Cyborg 009 lead-out, the exceedingly dark, tragic anti-hero has plenty of heft as his anime closes out. Between the impressive deployments, impressive weapons and action that rarely find its subject flat footed, Skull Man the character and Skull Man the anime rise to their promise in the works conclusion. The production isn't perfect. From the landscapes to the diners, Otomo City is successfully rendered as a specific place, geographically and economically. Yet, bits don't look right. Specifically, some of the 3D cgi models for cars and trains are a bit rickety. The Packaging isn't perfect. There's no English dub, which is a bit understandable for an anime that, in all likelihood isn't going to be a blockbuster. Due to music rights issue, the original opening wasn't used. The song didn't do much for me, but I think we missed out on some decent animation. The translation wasn't entirely consistent with previous North American Ishinomori releases. (Black Ghost versus Black Phantom). That's a nitpick, but it's the kind of thing that an audience with build in excitement for Skull Man would notice. The closest thing to an extra in the package is a collection of Japanese promos edited from material in the anime. Trailers for other release shouldn't are hard to consider value-adds, and DVD credits definitely shouldn't, especially when they run after the end theme on the trail of every episode. A live action prologue was produced for series' Japanese release, but that presumably was not part of the license package. The anime that I recommend to people who don't watch much anime or don't watch much anime anymore tend to be either of broad appeal (the Girl Who Leapt Through Time) or sensational in the tradition of what drew attention when anime was gathering notice (Rin, Shigurui: Death Frenzy). Skull Man is neither of those things. It's the work of creators who embrace material that's 40 years old with roots going back much further (it's hard not to speculate on Skull Man descent from kamishibai's Gold Bat.) It's not simply retro and it's not simply a ham-fisted attempt to adult up a kids' story. Instead, with the advantage of hindsight, it takes what worked about the original material, takes what's working in the current state of its medium, and uses the latter to amplify the former. In other words, the best sort of remake.