Sometimes here at AICN stories, scoops and interviews go to one person, when I would have given anything to have another do the same task. Here I have Moriarty... and he had the amazing good fortune to interview and speak and be in the presence of filmmaking GOD, Hayao Miyazaki. But many many miles away in Austin lay... sick to his stomach... Robogeek. Our resident Anime lover. More than that though there are only two people that Robogeek bows down and worships and credits for changing his filmgoing life. Miyazaki was one, Krzysztof Kieslowski was the other... whom Robogeek did get the chance to behold in his short time on this planet. But... as is often the case in this world, fate took a different path. And placed our resident Evil Genius across the table from this True Genius. Robogeek has been working non-stop setting this interview up, as well as arranging PRINCESS MONONOKE to be screened during the upcoming AUSTIN FILM FESTIVAL. One last thing before you move along. This week's RUMBLINGS is longer than usual and has been split up due to the limitations of this site's pre-programmed limits. At the bottom of the page you will see a link to the second part of the Rumblings containing many other fantastic bits from... Moriarty....

Hey, Head Geek...

"Moriarty" here.

The day started on a normal enough note. I rose early, made my way to the kitchen where several henchmen were preparing breakfast, found the eggs were slightly too salty for my taste, killed said henchmen, called in several replacement henchmen, killed them on general principle, then finally calmed down a bit. I'm not, generally speaking, a morning person. When one of the frightened mutants brought me my Palm Pilot so I could review my schedule, I was startled to realize that today was the day... a very special day... a day when I was set to meet a real-live, no-joke, if-you-don't-know-it-yet-you-should genius, Hayao Miyazaki.

I'd like to thank AICN's resident anime god Robogeek for helping me prepare for this interview and for making the whole thing happen in the first place. I can't even pretend to be an expert on the subject, which makes it convenient that we've got one we can reach by hotline.

I called up FreeRide, one of AICN's new spies, and asked him to bring over a copy of MY NEIGHBOR TOTORO for us to watch. When he finally showed up five hours later, dazed, breathless, and bloody, he tried to give me some line about how hard it was to locate the laserdisc copy of the Fox Video release of the 1995 American Troma dubbed version. He tried to explain how many stores he had to visit, how he actually had to knife-fight a clerk at Dave's Video (since I don't rent... I own), and then avoid capture by the authorities. All I cared about was the fact that I was going to be able to see the film before meeting the maker.

That makes three Miyazaki films I've seen now, and my respect for the man as an artist grows by leaps and bounds with each exposure to what he does. It was KIKI'S DELIVERY SERVICE first (dubbed, and I loved it, thanks), then a screening of the glorious new MONONOKE release, and now this dubbed version of TOTORO. I think the most remarkable thing about his work is the strong individual voice of each film. There's no mistaking who is responsible for these films. I know that KIKI is based on a book, but that doesn't matter. It's the gentle, spiritual tone of the storytelling, the perfect renditions of details both mundane and fantastic, the humanity of the characters.

Miramax has worked hard to introduce the phrase "Miyazaki is Japan's Walt Disney" into the popular consciousness over the last couple of years. You'll find it in every single press release they send out about him, and I think that's a perfectly fair comparison. Both of them are singular stylists, men who viewed animation as art. Both of them have created characters that have become iconic, cultural figures that overshadow individual films. I think there's little doubt, though, that Miyazaki is the greater artist of the two. His work is personal, profound, and there's such a centered philisophical center to the films I've seen that I find it hard to believe that even a frame of it passed through the hands of anyone but Miyazaki. It's the closest thing I've ever seen to pure imagination onscreen, the raw download of a director's dreams.

I remember my first viewing of KIKI. I had heard of the film and the filmmaker, but didn't really know what to expect when I found the recent Disney release for rental. I took it home, played it, and then played it again. And later that night, I played it again. It was the flying scenes that hooked me, but each viewing brought new moments into focus for me. Each viewing made me appreciate some new bit of character business or some stunning visual grace note. And on each viewing, those flying scenes held up, hypnotizing me. I'd never seen anything like it. When we fly in our dreams, unfettered of any machinery or gear or gravity, that feeling is the feeling that Miyazaki somehow captures. It's the ideal, as perfect as Sam Lowry's slow lazy tumbles through the cotton candy clouds of BRAZIL.

In TOTORO, there are all sorts of images that I will have to see again to fully appreciate. I can't wait to get another look at the CatBus, a startling creature that owes at least a slight visual nod to Lewis Carroll and Tenniel's classic rendition of the Chesire Cat. I am fascinated by the dustbunnies and the Totoros. And once again, I was touched by these characters. Mei, in particular, struck me as one of the more realistic child characters I've seen in a film. The simple, aching story of two sisters who escape their fear for a sick mother with the help of a set of spirits that only they can see is a perfect example of how Miyazaki somehow constructs strong dramatic pieces that avoid the simple black-and-white "good guys" and "bad guys" of most films.

I had such a good time watching the film that I was almost late leaving the Labs. FreeRide offered to drive, and he's got a spiffy new hovercraft I have been dying to ride in, so we headed out, managing to make it from my place to the Four Seasons Hotel in less than eight minutes. Several laws and windows may have been broken en route, but so be it. As it was, the interview before mine was running a bit late, so I had a chance to speak with the lovely people from Miramax who made this possible. I have this to say to anyone who's worried that Miramax "doesn't get it," or that they might not support the film enough; they get it. They sounded just like me, still new to Miyazaki's work, enchanted by it, still caught up in the rush of having found it. They spoke about how he once bought a WWII airplane that he flew across the desert just to get a feel for it. They spoke in depth about their reactions to key scenes from MONONOKE. And unlike most publicist speak, this was real. They think he's just as much of a rock star as I do. There's a feeling, like you've just figured out a secret, when you get turned on to his films, and I'm hoping that the major push MONONOKE is about to get will spur more Americans to get in on that secret. I know TIME magazine is planning a major piece on the film and Miyazaki's past work, and Roger Ebert is definitely a convert. He sat down with the director yesterday, and I can't wait to read about their chat.

When I entered the room where we'd be speaking, I was introduced to Linda, Miyazaki's translator. As I got settled in and went over my questions, I noticed there was a camera crew setting up. Since I'm wanted in 47 countries, I'm not wild about being videotaped, so I asked what was going on. The crew turned out to be shooting a documentary on Miyazaki. I wasn't planning to be on camera, and I would have worn my good glass eye if I had known. Still, all concerns about my appearance vanished when Miyazaki came into the room. A man of medium build, he has a riveting gaze and an easy smile, both of which he fixed on me as we were introduced. We shook hands, took our seats, and dove right in.

MORIARTY: Let's start today by talking about flying. One of my personal pet peeves in live action films is flying sequences. They can't help it... they always look fake. In your films, though, there's a poetry to flight. There's the midnight flight in TOTORO that feels like a warm-up to KIKI. Is flight a long-time passion of yours, and where does your sense of it come from?

MIYAZAKI: Ever since I was a boy, I have always liked airplanes. I've always been interested in flying. This is one of the questions I am often asked, and I can't really explain why this is. For better or for worse, there's no flight in MONONOKE, so no one can say that all my characters have to fly.

MORIARTY: Another hallmark of your work is the way you treat your children characters. In American films, both live-action and animated, children are portrayed as small adults, wise beyond their years. You write children as they really are. You capture each specific age. How do you approach the writing of your young characters?

MIYAZAKI: I've found that it's often true that when you start making a film, you call on your memories from that age. Your hopes from that age, your desires from that age, they're all resurrected. If you're writing about someone who's 10, you have to remember what that was like. As you work on the film, though, I find that imagination takes over.

MORIARTY: I was hoping you could talk a little bit about one of the key collaborations of your career, your work with composer Jo Hisaishi. In particular, I was wondering how you felt when Hisaishi recently rescored your 1986 film LAPUTA: CASTLE IN THE SKY. Are you happy with the new work?

This is when Miyazaki let loose with the first instance of what I will call his "thinking noise." It's a long, slow exhale, not quite a groan but almost. I thought at first I had asked something wrong, and I wondered how far the door was if I had to bolt from embarrassment. Miyazaki took a long moment, though, to really think about the question before answering, his smile back and playing on his face as he spoke.

MIYAZAKI: Jo Hisaishi and I have had a long term collaboration, and whenever I start work on a new film, I always go out and gather CDs in an effort to find someone better to write music for me. In the end, I always have to crawl back to him when I realize there is no one better.

I am not really an advocate of using wall- to-wall music in a film. I like silence. I can understand the anxiety for the studio, though, and it was important to them to add more music. None of it matched, though, so [Hisaishi] ended up recomposing and rerecording the whole film. I've heard it, and it seems quite lovely. I decided to allow it, but only if Jo was going to allow it. When we work on a film, we have meetings where we will discuss it back and forth and decide where the score goes. We will watch the film and say, "Put some music here and here and here," and when I am making my final edit, I always want to pull some of it out. "Cut it here and here and here." We have had our share of fights. I decided to let [Hisaishi] do whatever he chose with this as a gift.

MORIARTY: I've read that you did an astonishing amount of the work on MONONOKE yourself. Of the film's 144,000 cels, you were said to have pencilled 80,000 personally. Many of KIKI's flying sequences were handdrawn by you. As animators around the world rush to embrace new digital tools, what would you say to them about the place of the artist in the process?

When the translator read Miyazaki the question, he laughed, then shook his head.

MIYAZAKI: First, let me correct a misconception. I did not draw 80,000 cels. I frequently would correct or refine drawings to bring them up to a certain standard of excellence, but I didn't work on that many from scratch. When you are making a film like MONONOKE HIME, you create a standard that all the artists must use. If you have to, you redraw things to bring them to that standard. I am fortunate enough to work with many artists whose work is already well beyond that standard, and I do not have to do a thing to their work.

I would say that no matter what advances are made in animation, the animator just becomes more and more valuable. It's imagination, and not technology, that is most important.

MORIARTY: That would lead me to my next question. With MONONOKE, you finally embraced the use of certain CG elements in your picture. Can you describe your experience with these new tools?

MIYAZAKI: Originally, we decided to create a team that would render the boar god from the beginning of the film using CG. We wanted that for the spirit snakes coming out of him. We tried and we tried to do it that way, but in the end we had to go back to handdrawn for that scene. By that point, we were already farther along in developing some of the scenes, so we went ahead and used the computer there. I wish in some ways we had just done the whole thing by hand.

The only reason we even put the boar scene into the script was because we thought we were going to be able to render it with the computer. If I'd known how hard that was going to be, I never would have said yes to it. I suppose I have to say "thank you" to the computer.

He couldn't contain his amusement at this concept, and he worked to stop laughing as I asked my next question.

MORIARTY: Lady Eboshi is hardly what I would call a conventional villain in MONONOKE. In fact, all your films seem to studiously avoid black-and-white stereotypes about good guys and bad guys. Is it important to you to avoid villifying characters?

Once again, the thinking noise prefaced a long silence. Miyazaki thought about it, then chose his words very carefully, looking directly at me and speaking with real conviction.

MIYAZAKI: A true villain -- someone who manages to live with a hole where their heart should be -- doesn't interest me in the least. If they don't interest me, they aren't going to show up in one of my films.

I went to ask another question, but Miyazaki wasn't finished. I could see he was still thinking about it, and I waited until he spoke again.

MIYAZAKI: I haven't seen SILENCE OF THE LAMBS -- not all of it, anyway -- but I've read it, and that villain that's attractive. I find that very interesting.

MORIARTY: In discussing MONONOKE with people, I've heard some concern that the film might be too spiritual, too historically distant, too culturally removed for the average American viewer to enjoy. What, if anything, would you say to someone to prepare them for the film?

MIYAZAKI: I guess they'll just have to see it. If they don't like it or they don't understand it, my words here aren't going to help. I don't think I need to prepare people, though. We as human beings have more in common than we don't. We are, at heart, the same. This film, it comes from the same spirit as TOTORO. These films come from the same place in me, and I think they will speak to that same place in other people as well.

MORIARTY: You spent well over a decade preparing to make MONONOKE. You did pencil sketches of San as early as 1980. Now that the film is rolling out to audiences around the world and you've had some time to live with the film, are you satisfied? Is it what you had hoped it would be?

Once again, the thinking sound. Miyazaki sized me up as he considered the question. When he spoke, it was so soft that I had to lean in to hear him.

MIYAZAKI: I can't answer that yet. I think we'll have to wait at least 10 years before I can know. We need to wait until all those children who are just 10 now who are seeing the film grow up, until they're 20 years old. We'll have to wait to see what impact it has on them, on their relationship with the world. To me, you can't measure the success of a picture on how many tickets it sells. You can only measure it in how many hearts it changes.

As I made my notes, Miyazaki watched me, smiling.

MIYAZAKI: For someone who is on the Internet, you write by hand quite fast. You write a lot. It's like being a traditional animator. You've got your computer, you can do it that way, but still...

MORIARTY: I prefer this way, actually.

He just smiled, nodded, his eyes dancing. I got the sign from the publicists that we had five minutes left, so I flipped through the stack of questions I brought. Many of you were kind enough to send me suggestions, and I'm sorry if I didn't get to yours. I appreciate the effort, and I'm just sad that the time raced by as quickly as it did.

MORIARTY: The films of yours I've seen so far -- KIKI, TOTORO, and MONONOKE -- all take place in real historical periods, or at least identifiable ones. You've said that KIKI takes place in a Europe where WWII never happened. TOTORO is obviously set in the early '50s. Even MONONOKE, which feels like total fantasy, is set during the Muromachi period of Japanese history. Into these very real settings, you then interject the magical, the fantastic. How do you define these worlds for yourself, and why the juxtoposition?

MIYAZAKI: Because otherwise it would be boring.

(laughs)

I always struggle about what age to set a film in. For TOTORO, it was very particular, very precise. I knew it had to be set in 1953, when there was no TV to intrude on the lives of children. It's that last moment, when imagination is still important, before 1955, when TV arrived. For MONONOKE, I had to set it then. The Kamakura period, the time right before the Muromachi period, would have been incomprehensible to modern viewers. As far as KIKI is concerned...

(laughs again)

KIKI was the result of a bet I made to someone. I bet that I could create a world with both modern elements and things from the past, and children would never question it. Sadly, I won.

MORIARTY: And finally, sir, I would be remiss if I didn't ask what we can expect in the 21st Century from Hayao Miyazaki.

MIYAZAKI: All I know is that my next film will be set in Japan, in a version of Japan where fantasy and the modern world are combined. Even here, even while I visit with you, even while I travel, I lie awake at night, moaning, worried about what shape this film will take.

His translator added a sincere,

"He's not kidding,"

and that was that. I started to pack up, and the translator noticed that I was carrying with me a copy of the superb new Hyperion book PRINCESS MONONOKE: THE ART AND MAKING OF JAPAN'S MOST POPULAR FILM OF ALL TIME. It's a gorgeous hardback coffee table book, loaded with exquisite art, filled with poetry that Miyazaki wrote for his screenwriting collaborators as well as Hisaishi, to guide him when scoring. I'm not going to pretend I went in there without ulterior motives, but I didn't want to ruin the mood by forcing the book on him. Linda spared me the trouble, though.

"Is that for an autograph?"

"I'd be honored," I said.

"I think he had a good time. I think it's okay."

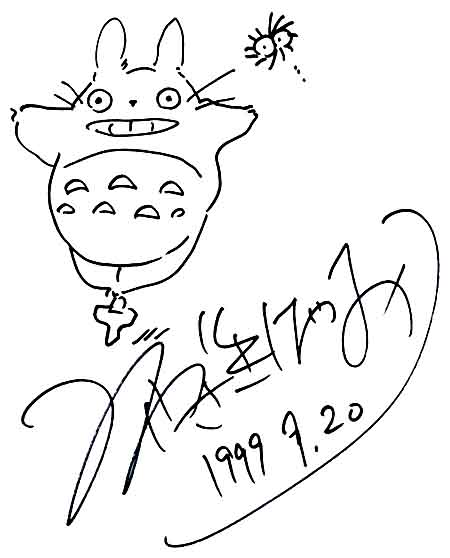

She took the book from me and offered it to Miyazaki. I passed over a Sharpie, and watched, eyes agog, as he drew me a quick sketch of Totoro and a dustbunny, then signed his name and dated it.

He said something as she passed the book back over to me, and she translated it.

"He says Totoro hasn't gotten enough sleep. He looks wild."

I was so amazed by the drawing that I barely remember the rest of the process. I know we got up, said our good-byes, walked out, somehow made our way to the car. I also know that today was one of those rare, special moments where you bask in the best of being a film geek. All this useless clutter I've accumulated upstairs all these years, these facts and box-office figures and filmographies and credits and dialogue snippets, all pay off on a day when I am invited to sit down with someone like Miyazaki. Here's the Totoro drawing, something special for you to share.

Hopefully that just whets your appetite for more of the man's work. If so, find the MONONOKE book. It's not just beautiful, it's also an exhaustive look at the process of bringing this film to the screen, and it's a real testament to that exhaustive detail work that makes Studio Ghibli's films so unique. I know that the book and today's interview and my morning show of TOTORO have all made me rabid for September 30 to arrive. That's the day UCLA is kicking off their special presentation, STUDIO GHIBLI: THE MAGIC OF MIYAZAKI, TAKAHATA and KONDO. It runs through October 10, and promises a comprehensive look at the output of Miyazaki, Isao Takahata, and Yoshifumi Kondo, with screenings that include a sneak preview screening of MONONOKE, Takahata's GRAVE OF THE FIREFLIES, and Kondo's debut picture WHISPER OF THE HEART. As with all UCLA Film and Television Archive programs, you can call 310.206.FILM to get detailed information. You should try and join me at the films mentioned above, or NAUSICAÄ, ONLY YESTERDAY, CASTLE IN THE SKY, and PORCO ROSSO. I plan to savor each and every moment.