Greetings! ScoreKeeper here still jitterbugging with joy after my recent conversation with the gentleman who penned my favorite score of 2009.

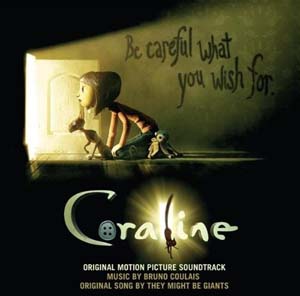

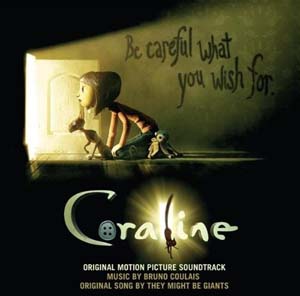

About a week before I published my top ten best scores article of 2009, I received an offer to interview French composer Bruno Coulais, who wrote an epically exquisite score for Henry Selick's stop-motion animated masterpiece, CORALINE (2009).

Bruno called me from Paris where he lives and works. English is not his primary language but he did a great job communicating his thoughts and feelings to me. Being a typical mono-linguistic American, I couldn't even read French if it were written out in front of me. Color me impressed.

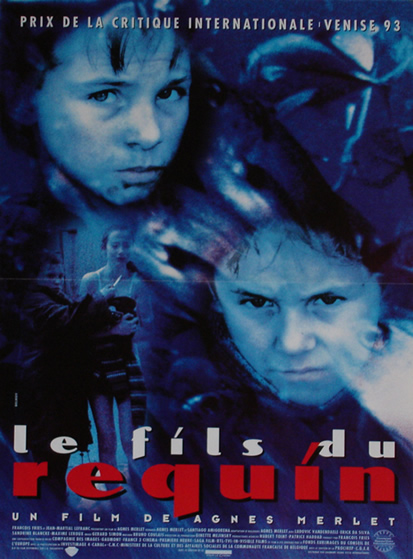

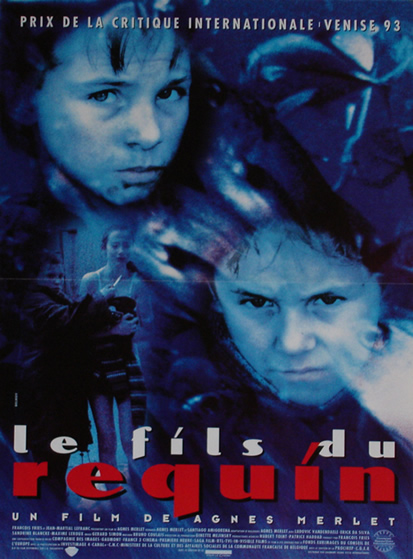

Later in the interview we even discuss one of my all time favorite foreign films…LE FILS DU REQUIN (SON OF THE SHARK, 1993) which was directed by Agnés Merlet and scored by Bruno Coulais. His music for this film is utterly sublime. Scored for mostly string quartet, it's built upon a simple slow waltz in a minor key with a haunting melody floating peacefully on top. There's even a childish ditty that permeates the score in various disguises. It's a "small" score for a very powerful and surprisingly violent film.

A CD was released but went out-of-print a long time ago. If I were to dust off one score and re-release to the world, SON OF THE SHARK would be my choice. Until that happens…we'll just have to enjoy the rest of Bruno's amazing work.

I hope you enjoy the interview.

ScoreKeeper: Hi Bruno! Good morning…or I guess it's afternoon for you, right?

Bruno Coulais: Yes. I hope it's not too early for you.

SK: No. I've got small kids so I'm usually up pretty early. This works out really well for me.

BC: Thank you very much for the interest you have taken with my music. I'm very proud of it. It's really an encouragement for me.

SK: Well, thank you. It's my pleasure to have you on the line and be able to talk with you. I don't know if you've seen it yet, but I published my top ten scores of 2009…

BC: Yes! I saw the list and it's wonderful. Thank you so much.

SK: I would like to start at the beginning. Can you tell me how you were chosen to be the composer of CORALINE? Did you pursue the position yourself or did it come to you?

BC: No. It was the idea of Henry [Selick]. I think it needed my kind of music. He tried a lot of things. I don’t know why or when but he used the music I made for MICROCOSMOS (1996) and WINGED MIGRATION (2001) and he thought that my music worked in the movie so he called me. I was very happy because I have a lot of admiration of Henry’s work. I am a huge fan of THE NIGHTMARE BEFORE CHRISTMAS (1993) so it was really a great surprise for me.

SK: It’s interesting you mentioned Henry temp-tracked CORALINE with your music from MICROCOSMOS and WINGED MIGRATION. Those are two very different scores than the music you ended up composing for CORALINE.

BC: Temp music is always a problem. I think it’s very daunting. Very often when I discover a film I see it with temp music and I think it’s limiting for the composer. That kind of thing limits the field of exploration. Do you understand what I mean? Maybe the fact that it was my music, regarding CORALINE, was easier for me because I tried to write very different music, but I think I understood what Henry liked in that music and expected of me for CORALINE.

SK: Did it present an obstacle for you initially? When you played Henry those first few pieces of music was he immediately happy with them?

BC: It was very strange because I think the world of Henry is very close to mine. I first composed four or five melodies – especially the melody for Coraline and Wybie and the Other Mother - and Henry seemed happy with these. So the first contact and the first work went well. It was very strange because we were so far from each other and yet the contact was incredibly close and very fast. He would send me some sequences from the film, I worked on them, and I sent him demos. The answers from Henry were very fast and it was very simple.

When I work with a French director, they take their time, but with Henry…Creating the whole soundtrack with someone like Henry was great.

SK: That’s fantastic. Did the long distance collaborative relationship work well?

BC: The long distance did make the communication very easy and felt very close. I received the sequences and immediately I had an impression and reaction. I think the intuition worked very quickly. With the long distance I was able to do that. Sorry…my English is terrible.

SK: It's fine. You're communicating very well. So was Henry very active in the collaborative process or did he just unleash you and allow you to do what you wanted to do?

BC: He wasn’t too directive. It was great because it was based a lot on my first reaction. He let me be very free. I think he's so gifted and his world is so fantastic. He's so into his work and it's so precise. The music is mine but at the same time it's the music of Henry. It's the same thing as with all gifted directors. Sometimes he would want to change something but fairly often we were on the same page.

SK: Behind every great score there is a great director. As much as I love your work in CORALINE, I think a lot of credit needs to go to Henry for picking you and trusting your intuition. Not every director can be that daring.

BC: For me the best directors are the directors who let the composers do their thing. I think all the directors out there are very anxious about music because it’s another world which comes very late in the process. They are very often surprised. I think Henry wanted to be surprised and pushed me to be very free and use my imagination. I think he didn’t want just normal music. He wanted something very special and personal.

SK: One of the aspects regarding the score that I'm so attracted to is the sheer eclecticism of it. There are so many different flavors and styles and instrumentation choices. From beginning to end you cover such a huge musical spectrum and demonstrate a prodigious musical vocabulary. Yet, the score as a whole feels very unified. This can be an incredibly difficult thing to achieve. How did you balance the creative freedom granted to explore so many ideas, yet manage to maintain such a strong sense of unity?

BC: I think the narrative sense gives an ideal unity for the score. We had the same ideas and the duration by the orchestrations and the starts. For me it’s very important when I compose for a movie, especially for CORALINE, to have an idea about the structure of the music in the film, not just the first sequence and second one and so on, but to have a long construction. With CORALINE, I worked chronologically because I felt the characters were changing and so the music had to change – the style, the orchestration and the humor and all of those kinds of things. I think the unity comes from the melodies or at least I hope.

SK: Was there ever a moment when you were composing where you were feeling like it was starting to unravel?

BC: Yes. Very often I would change my mind. It’s frustrating because when I start a new film, I have no ideas. I sometimes feel I lose focus. But then things become clearer. When I compose I always have the idea of the orchestration and it’s very important for me to create a melody with an instrument. It’s very important to think of what the atmosphere is like. I am unable to put some melodies on specific lights or colors with atmosphere so it’s intuitive that I think about the orchestrations.

SK: A lot can be told about a composer's creative process by the first piece of music written for a film. What was the first piece of music you wrote for CORALINE and how did it fuel the creation of the rest of the score?

BC: The first piece I believe was the credits and it was very funny because with Henry we wanted the song…We wanted a singer and I hate my voice but I needed to show him what kind of interpretation I wanted for the music. So I sang a song and throughout the way we were trying to find a singer. At the end Henry wanted to keep the voice. I was very surprised but I think the head credit music is very important because they give the atmosphere. It’s very important at the beginning of a film to use music. I look at it like the opening of an opera, you know. It provides all of the sentiments and feelings you want to get across and the impact on the audience is very important. Every time it’s very important for me to concentrate on the head credit music.

SK: What was the most important thing that music hade to accomplish in CORALINE and do you feel you achieved it? If so, how?

BC: I think emotion. I don’t know how good of a word emotion is in English but in French…I think if the audience is moved by the music…like is terrified or moved…It was very interesting to create some longer pieces and it’s very interesting for a composer to try to bring emotions out with music. It’s not so easy because I try to not use too much theatrical music to express the feel. I think sometimes to infuse childhood into music helps so that’s why I used children’s voices or toys or just things involved with childhood on CORALINE. It’s difficult to express these ideas.

SK: Where did the idea of using nonsensical words as your vocal text originate?

BC: I think it’s dangerous to bring in sense with words. With those kinds of songs I can play with the music but I can also create and imagine new languages like the language of spirits. I hate the songs in the films who bring explanation about what we are watching in the sequence. For example nonsense is good for me…For me, music has no sense and I don’t like too bring too much attention with the music. I think music is like the light, another element of the director’s vision. It’s not fair to explain what we are doing in order to understand the situation of a narration.

SK: What did Henry think when you first told him of your idea to do this?

BC: I remember he was very happy with the idea of a nonsense language and he was very enthusiastic with that idea.

SK: Was it very difficult coming up with those sounds? Did you write them all out? Was it a difficult process or did you just let the sounds flow?

BC: No, because it’s like an orchestration or composition. It’s musical to approach the language with that so it was easy because when I imagined the melody I imagined it with these words. So we went with those words. It wasn’t so difficult. Another aspect which was very important for me on CORALINE was to put the music at the size of children. For example, the mouse circus was interesting for me to try with the music and orchestration to put the density of the orchestra in relation with the size of the mice but also the children as well.

SK: You use the voice a lot in your scores. Where did your love of the voice originate from?

BC: For me, it’s like an instrument…especially children’s voices. They bring something to it. Voices also sound spectral with songs sometimes. In CORALINE the voices are like doors and I think voices help to move the audience more than just the instruments of the orchestra. I love using voices, but not too much. Singular voices and combinations of different strange voices, to me, is very interesting.

SK: Were there any particular challenges or differences in scoring a stop motion animated film? Was the print that you were scoring from visually complete?

BC: I think the difference is the characters of CORALINE are so human and so pleasant and different from a traditional animated movie, so the music had to be very human, I think. When I watch CORALINE, I forget they are puppets on a stage, for me they are real characters and I was very interested in them all, especially the character of the Other Mother. For me, it’s my favorite character in the movie because, first of all, it’s obvious the director loves the bad character. I’m sure that Henry was in love with the character of the Other Mother and music can show the anxiety of the character of the Other Mother but also it can bring some emotions to bring some sympathy between the audience and this character.

SK: Yeah, she’s definitely the most complex…I don’t know if that’s the right word…perhaps most robust character in the film. She is the antagonist but you sympathize with her and feel sorry for her. It's a big responsibility for the music to add that layer. I can imagine that being a real challenge.

BC: The most interesting…It’s very difficult to put music on very happy or very simple characters…I’m not very good for comedies. I love all that is strange and I’m very fascinated by the darker characters. One of my favorite movies is EMMA (1996) and in CORALINE it’s the same thing, “Who is the bad character?”

SK: How do you think CORALINE differs from your other scores?

BC: In France the cinema is a place of rest. So I think I was absolutely on the same page with the world of Henry. I think it’s my world really and I am very lucky that I get to work on beautiful movies that are interesting, but with Henry, he was absolutely in place with what I wanted to do in cinema. With Henry and CORALINE, I could experiment and I love experimentation. I love to try something new on orchestration using special instruments like toys and voices and with CORALINE I was able to try all sorts of things and that’s very rare.

SK: I can imagine. Have you ever thought of moving to the Untied States to further pursue your career?

BC: Not at the moment but I would be very excited to. My experience with CORALINE was so unique and fantastic that I want to start another experience. I was also very impressed by the quality of the techniques and mixers especially. They were so ground with the songs. The quality of the songs and the mixing is very special so I think I would be very happy starting another experience.

In France I am happy too and have just finished a very interesting movie with a great director. He asked me to compose a concerto to violins and let me be absolutely free to compose what I wanted and we recorded it before shooting and that was very strange. During the editing we tried the music out at various places and it worked and it was a strange manner of working.

SK: What’s the title of the film?

BC: It’s called RAPTUS. It’s very dark and violent. For me it’s been a fantastic experience.

SK: I’ve been familiar with your work for more than fifteen years. You are one of those composers I’ve always admired and I was really excited when you were hired to score CORALINE. I was especially thrilled that US audiences might have the opportunity to become more familiar with your work.

The first film where I discovered your music was LE FILS DU REQUIN (SON OF THE SHARK, 1993) which I mentioned in my initial review of your score for CORALINE earlier this year.

BC: Yes, I know! It’s fantastic because for me it is a very vibrant movie and I loved to score it. I was very happy and proud that you noticed this work.

SK: It’s a beautiful film. To this day, I think it has the two greatest child acting performances of any film I’ve ever seen in my lifetime. The two kids in that movie were fantastic!

BC: Absolutely! I think the director, Agnès Merlet, is very gifted and this isn’t her best piece, but I think she is able to do new interesting films. I hope so. It’s true…the two kids were fantastic. They were so realistic. It’s a great movie, I think.

SK: You don’t see children completely absorbing their character like you see in that film.

BC: It’s true. We were looking at what type of music to compose on this film and it’s funny to bring violence with that kind of instrumentation, you know? Today I think there is a problem with music in most movies because if you don’t use a large orchestra, a lot of producers aren’t happy. It’s a pity that most composers aren’t allowed to be more inventive and to sometimes use fewer instruments to try something new.

SK: I totally agree. I’m a huge fan of chamber music film scores. They are so rare these days. I think in the past, twenty years ago and even longer, you heard a lot of these interesting instrumental color combinations. Today, orchestration is just a template. I wish there was more variety in instrumentation choices and combinations.

BC: It’s true and it’s a pity to use music like that. In France, almost all the edits use temp music. For me, it's the same thing because sometimes we do the same music or all the music has the same harmony, orchestrations, or feelings. It's stupid!

SK: Regarding SON OF THE SHARK, it’s practically impossible to find. It was available on VHS many years ago but quickly went out-of-print. Have you heard any word on any possible DVD release in the future? How about a possible re-release of your score?

BC: I don’t know. From memory, I think the DVD doesn’t exist, but maybe I can write to find out.

SK: As somebody in a position to talk about and recommend films…This is one that would be at the top of my list but it’s a film that nobody can see nor hear. It’s very frustrating. It’s such a great film.

BC: It’s a pity really. I hope that changes very soon.

SK: Well Bruno, that pretty much wraps up all of the questions I had. I want to thank you for taking the time out to talk with me today, it was a real pleasure and honor for me. I love your music and have for a long time.

BC: Thank you so much and I apologize again for my English.

SK: You've been great. Thank you!

BC: Thank you so much and for taking the time and interest in my music. I’m very proud of it. You have a good day and I hope to meet you soon.

SK: I’ll look you up the next time I’m in France.

[Both Laugh]

SK: Take care. Bye.

On behalf of Ain't It Cool News, I'd like to thank Bruno Coulais for taking the time out to speak with me. Special thanks also go to Melissa McNeil at Costa Communications and to Mike McCutchen for their invaluable help with this interview.

The score for CORALINE was released on CD by Koch Records (KOC-CD-4741) and is available for purchase at Amazon.com. It is also available as a digital download via iTunes.

ScoreKeeper!!!