For the first twenty-five, and a thorough explanation on my highly complex ranking methodology, read this. For the next twenty-five, read on...

75. THE 40-YEAR-OLD VIRGIN (2005, w. & d. Judd Apatow)

From another lost-to-the-void Collider review: "As is often the case in [Judd] Apatow's work, it's not so much the material but the character - an element lacking in many studio comedies nowadays. Of course Apatow can craft a gag like nobody's business, but he's able to balance his broad sensibilities with something recognizably human. Beneath the silliness of UNDECLARED lurks a truth wincingly familiar to anyone who ever muddled through a freshman year of college. And though there hopefully aren't too many forty-year-old virgins out there, who can't empathize on some level with Andy's sexual dread?"

This was Apatow's first film as a director, and it remains his most rewarding: though the youthful ensemble of KNOCKED UP is looser and more comfortable with each other, the cutthroat competition for laughs in THE 40-YEAR-OLD VIRGIN results in more inspired riffing. And when Apatow expanded the picture to 133 minutes for the unrated DVD, the additional scenes were all gems. Hell, even the blown takes were terrific (e.g. Gerry Bednob's addled invention of a new sexual position called the "Alligator Fuckhouse"). I guess you're supposed to hate Apatow now that he's established an aesthetic, but, really, would you rather studios return to the '90s glory days of high-concept comedy? Or how about shoehorning all of Apatow's discoveries into formula dross like YOU, ME AND DUPREE or THE UGLY TRUTH? How about a remake of WEEKEND AT BERNIE'S with Jonah Hill, Jay Baruchel and Dave Allen as Bernie? No? Then why don't you leave the man alone.

74. AMERICAN SPLENDOR (2003, d. Shari Springer Berman and Robert Pulcini, w. Berman and Pulcini)

This highly inventive adaptation of Harvey Pekar's long-running comic book - which stars Paul Giamatti as Pekar, a well-read curmudgeon eking out a living as a Veteran's Administration file clerk in Cleveland, Ohio - seamlessly blends real life and dramatic recreation to the point where the protagonist's life feels as if it's been one long (kinda cruel) experiment in mundanity. Berman and Pulcini cleverly get you laughing at Pekar's predicament before clobbering you with the epiphany that a) most lives are this crushingly uneventful, and b) you'll be blowing out the candles on that retirement cake soon enough. A rare, perceptive film about working class intellectuals. Giamatti's performance ranks among the decade's best (which, of course, means he wasn't even nominated for an Oscar).

From my 2003 AICN interview with Harvey Pekar: "This is not to say, however, that Pekar’s outlook isn’t unremittingly bleak. The sixty-something writer doesn’t seem any happier now that he’s retired from that soul-snuffing job as a clerk at a Cleveland VA Hospital. To wit: at the end of the movie, Harvey undercuts his acknowledgement of the potential windfall from doing the movie by noting that there’s just a short window of opportunity left open to him after a life of hard work, lamenting that his family life isn’t any less contentious or complicated than it was ten years ago. But if Harvey’s reward is more tsuris, our reward, then, are more comics, which ain’t so bad for either of us."

73. THE FOUNTAIN (w. & d. Darren Aronofsky)

Darren Aronofsky's madly ambitious film about the quest to not die, and to not let anyone we love die, leads with its soul and succeeds because the writer-director never once tries to over-intellectualize the experience. He just wants to break our heart. In trying together three not-too-disparate stories - about a conquistador's search for the tree of life, a cancer researcher's attempts to disappear his wife's brain tumor, and a future dude's intergalactic journey with a dying tree and his deceased wife's ghost - Aronofsky evokes deep sadness as we have our silly hopes crushed once again. Life and love are fleeting, loss is inevitable, and there ain't a damn thing we can do about it.

THE FOUNTAIN is the heartfelt flip-side to the oppressive nihilism of REQUIEM FOR A DREAM. It's also Aronofsky's finest film to date. Sadly, Clint Mansell's lovely score is now being used to sell insipid Hollywood product. If you love this film as much as I do, this cue should wreck you every time you hear it:

72. UNITED 93 (2006, w. & d. Paul Greengrass)

From my 2006 Collider review: “As for unflinching, documentary-style recreations of actual events, United 93 is as relentless as Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (though, obviously, much more contained and much, much less political). Greengrass has no intention of sparing the audience any of the ugliness that transpired on the ill-fated flight, particularly in the grisly third act, and his ferociousness will certainly prove too much for more sensitive viewers. As someone who viewed the smoldering Twin Towers from the twenty-sixth floor of the MetLife Building in midtown Manhattan, and, like so many other New Yorkers, glumly went through the motions for a week or two following the attack on our city, I often wondered what the hell I was doing in the theater. Aside from bearing witness to Greengrass’s maturation as a filmmaker (and this is easily his most accomplished work yet), I spent most of the moments prior to the start of the film trying to figure out why I’d bothered.

...[But] that’s why United 93 needs to exist, and why I think it will become an important, widely-seen documenting of the day everything changed for Americans. We need to remember the heroic deeds in the early hours of 9/11, and, for the sake of unity, we don’t necessarily need politics to enter into it. That said, the apolitical nature of Greengrass’s film may wind up rendering it a little quaint once writers and directors grow a bit bolder in tackling the subject. Rossellini’s Open City and Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers still resonate today because they have a contentious point of view; though far from timid, the objective United 93 is ripe to eventually get overshadowed by more opinionated works.”

Even if those works come along in the next decade, UNITED 93 will always be a chilling and boldly unsentimental reminder that that could've been you or me on that plane. Several years after its theatrical release, this film now feels incapable of being overshadowed.

71. THE HOLY GIRL (2004, w. & d. Lucretia Martel)

A vast improvement over her first movie, LA CIENAGA (which felt like a study of human beings struck inactive by extreme humidity), THE HOLY GIRL finds Lucretia Martel figuring it out as she goes along - both as a director and a storyteller. Whereas little seemed to coalesce by the end of LA CIENAGA (thematically or narratively), everything sort of slides into place here, and what at first threatens to be a morality play about a middle-aged doctor's improper contact with a teenage girl (brought on by, what else, a theremin) gradually turns into a mediation on the absence of innocence. At least, that's my take. Martel's film is generously open-ended - even though it's also put together with a deceptive precision. She's a major talent. (And I must shamefully admit that I have yet to see THE HEADLESS WOMAN.)

70. BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN (2005, d. Ang Lee, w. Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana)

From my Best of 2005 for Collider: "When Ang Lee was told BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN, which utilizes young actors to tell a multi-generational tale of societal discovery, could be viewed as “GIANT turned inward”, he smiled and shot back, “Or GIANT turned outward”. Such irreverence may have been unexpected after the heartbreak of his lushly romantic epic, but that puckish comment underscores the wry humanity present in all of Lee’s films. Sure, he tackles weighty topics with occasionally tragic outcomes, but you can’t get to the wounded core of your characters without a touch of levity, which is abundant in Jack and Ennis’s gradual, unexpected courtship at the outset. Working from a fantastic script by Larry McMurty and Diana Ossana, Lee avoids the pitfalls of obviousness at every turn, right up to the pulverizing finale where the emotional understatement of all that’s come before pays off in well-earned tears - at which point BROKEBACK equals the impact of its fifty-year-old progenitor with a far more economical use of screen time. (It’s also important to note that, like George Stevens, Lee is not revising the Western genre; he's seeking to redefine an archetype much bigger than its filmic representation. In other words, comparisons to other Westerns are awfully limiting.)

I had no idea how apt those GIANT comparisons would be three years ago. And even though we got more, quantity-wise, from Ledger, the thought that he exited right at the moment he was coming alive as a performer is anything but comforting.

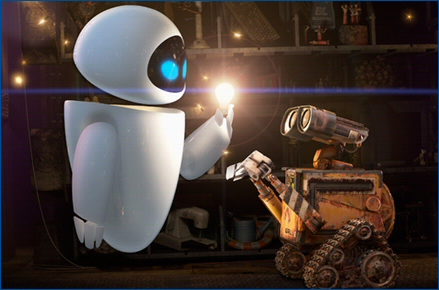

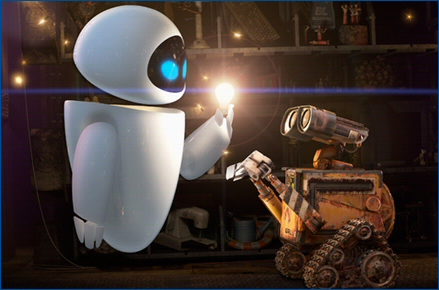

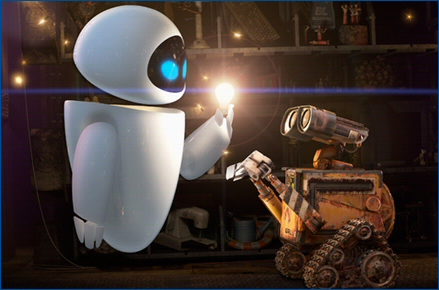

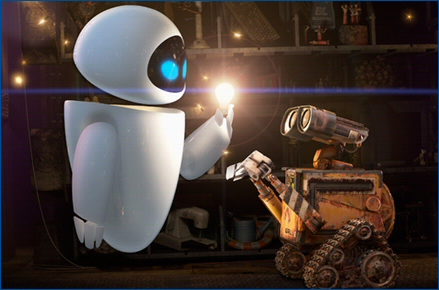

69. WALL-E (2008, d. Andrew Stanton, w. Stanton and Jim Reardon)

From my 2008 AICN review: Despite the gentle, MODERN TIMES-inspired satire, "true love" is the motor of this story. It's a lovely gesture, and it makes me smile, but there's a part of me that wonders whether we'd be referring to Stanton's film as genuflectingly brilliant if he left WALL-E's memory wiped at the end. Most all-ages classics require some semblance of sacrifice: we assume Elliott will never see E.T. again, whilst another noggin-knockin' trip to Oz would probably leave Dorothy talking like Leon Spinks. But after a few we-know-you're-not-going-there scares, WALL-E gets rebooted and is shipshape once again (like Uhura post-"The Changeling").

On second thought, since I've made a similar argument in defense of Tom Cruise's kid "miraculously" returning at the end of Spielberg's WAR OF THE WORLDS, I'm going to be consistent and say the ending is exactly what it needs to be: WALL-E lays out for "the needs of the many", and he is duly rewarded by not being reduced to a memory-wiped droid. This doesn't mean WALL-E is now "genuflectingly brilliant", but it is top-shelf Pixar - and that's more than good enough to place here.

68. SUPERBAD (d. Greg Mottola, w. Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen)

From my Best of 2007 list from CHUD: "The return of Greg Mottola (director of the underrated and underseen The Daytrippers), the debut of Christopher Mintz-Plasse (the Anthony Michael Hall of his generation if he's unlucky, which I don't think he'll be) and more stellar Apatow. Everyone jokes that there's going to be a backlash at some point (maybe the box office failure of Walk Hard is an indication of this), but why? As long as the company keeps expanding, and the leads keep changing (though Seth Rogen is a bona fide superstar, and could do with a movie a year), what's there to resent besides success? In a way, I think Superbad points the way forward: it's the Apatow aesthetic in the hands of a filmmaker with a completely different skill set. It's also (in its theatrical incarnation) the tightest of the Apatow flicks thus far."

Two years later, it still is. Though the comedy gets pretty broad at times, SUPERBAD effortlessly exudes that universal, wild-night-out feel that made DAZED AND CONFUSED an instant classic. This is largely the doing of Mottola, who followed this up with the ADVENTURELAND, a bittersweet evocation of post-college ennui that deserves a much wider audience. I love both films, but SUPERBAD hits so many highs (Cera enchanting a roomful of cokeheads with his frightened rendition of "These Eyes"; Carla Gallo leaving her mark on Hill's pants; that nervous/giddy moment before Mintz-Plasse empties Hader's service revolver) that it just barely gets the nod.

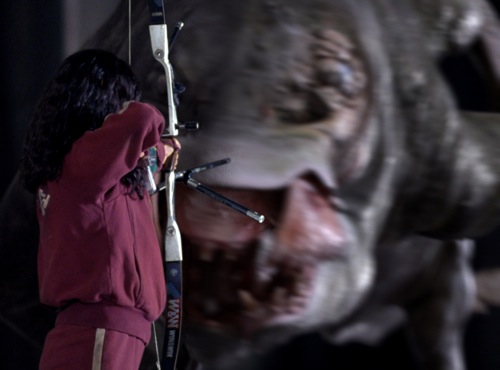

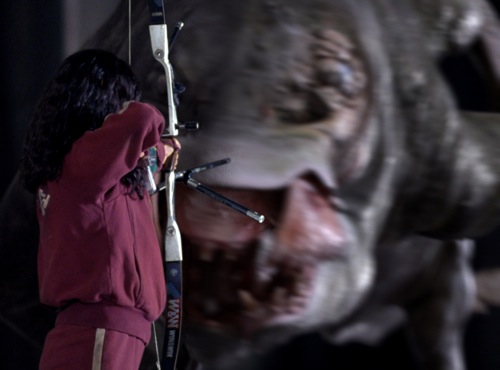

67. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE (2009, d. Spike Jonze, w. Jonze and Dave Eggers)

A film that could very well move up this list as the years pile on.

I haven't gone back since my first viewing, but the final scene - where Keener falls asleep watching a safely-returned Max scarf down his dinner without a care in the world - hits me hard. Though we didn't realize it at the time, we all participated in those moments - where our mothers found solace in us just being happy and young and theirs. And you get the sense that Keener hangs on to consciousness for as long as she can because she knows how fleeting this all is. In a few years time, Max will enter middle-school, and this bond will dissolve. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE strikes many resonant, melancholy chords, but in the end, it just made me miss being a kid for my mom. And that's why it made me sad.

I also think the final shot of ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND is a complete downer, so if I'm alone in this reading, so be it.

From my 2009 AICN interview with Spike Jonze: "While WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE feels like a deeply personal film for Jonze, its depiction of a bratty kid run amok - and away to an island of moody monsters - is also incredibly inclusive. The specifics of Max's childhood may not resemble yours, but the highs and lows he experiences should be painfully familiar. No film has more perfectly captured what it feels like to be nine years old."

66. THE CONSTANT GARDENER (2005, d. Fernando Meirelles, w. Jeffrey Caine)

Beats the tar out of THE LITTLE DRUMMER GIRL. From my 2005 review for Collider: "It took a filmmaker as prodigiously talented as Fernando Meirelles to finally transfer John le Carré successfully to the screen, though his accomplishment reaches past the angry espionage of the novel to discover a doomed romanticism reminiscent of Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient. Borrowing that film’s lead (the great Ralph Fiennes), Meirelles has skillfully constructed a love story in which affection is not truly requited until both parties are murdered. Rachel Weisz’s Tessa Quayle hastens her death questing justice; Fiennes’s Justin Quayle brings about his by taking on Tessa’s cause after jealously investigating her possible infidelity. Justin’s a horrible sleuth, the meek antithesis of Harry Palmer, but Meirelles and le Carré aren’t after a rousing thriller in that mold. And though the movie brims with righteous indignation, it isn’t a political tract, either. What stays with you is the thought of Tessa and Justin reaching the same terminus alone."

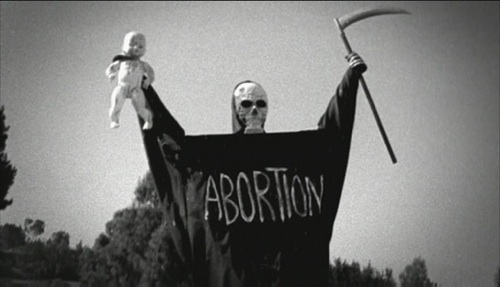

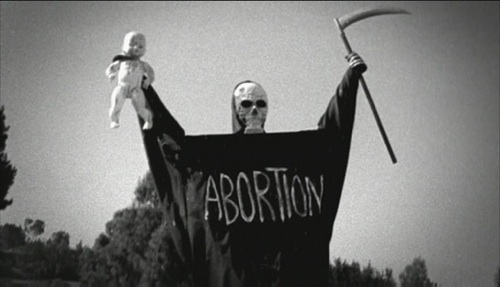

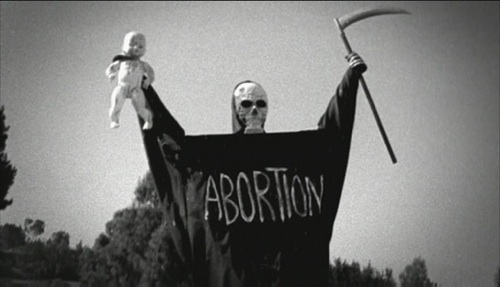

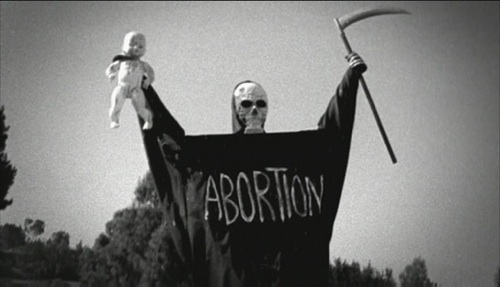

65. LAKE OF FIRE (2007, d. Tony Kaye)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "I knew where I came down on the abortion issue before I saw Tony Kaye's Lake of Fire; afterwards... I was a lot less certain. An objective and exhaustive documentary examining both sides of this roiling, often violent debate, Kaye challenges our preconceived notions by juxtaposing the tired, talking-point spiel regurgitated by the rank-and-file with thoughtful analysis from journalists like Nat Hentoff (who skillfully, if not entirely persuasively, argues the inconsistency of being anti-death penalty and pro-choice). But don't mistake this for a talking heads affair; Kaye reminds us, with his brilliant black-and-white cinematography, that he's one of the most visually gifted filmmakers working today. He's also unflinching in his depiction of the actual process of abortion, the aftermath of which will surely be too much for most viewers. Sensationalism aside, Kaye's still made the most thorough and even-handed documentary on this deeply divisive subject."

64. TIME OF THE WOLF (2003, w. & d. Michael Haneke)

This unusually straightforward work from Michael Haneke is about a French family struggling to cope with the end of the world as we know it. Haneke skimps on the catastrophic particulars and instead focuses on the collapse of society - which has been depicted hundreds of times before, but rarely with this level of verisimilitude. Isabelle Huppert is sensational as the mother fighting to protect her children and maintain civility as the strangers they encounter gradually give in to their basest survival instincts. What's surprising here is Haneke's near-acknowledgment that order can be reimposed; inevitably, as long as the planet's not in a sere shambles or a pipin' hot ball of fire (hey there, Alex Proyas!), we will rebuild. This is the one Haneke film that helps you up after it knees you in the nuts.

63. KAIRO (2001, w. & d. Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Hands down the best J-horror film of the decade - so long as you're counting AUDITION as a 1999 release. Though its "gimmick" of spooky images being captured via webcams feels incredibly quaint nowadays, Kiyoshi Kurosawa's 2001 classic is still an impeccably-crafted, slow-burner of a ghost story. As with most films of this subgenre, the set pieces are pretty much the show (this fucker is an unrepentant nightmare machine), but there's an unexpected scale and thoughtfulness to Kurosawa's story that's more Romero than Shimizu. Unlike RINGU or JU-ON, repeat viewings are anything but a case of diminishing returns.

62. TIME OUT (2001, d. Laurent Cantet, w. Cantet and Robin Campillo)

Laurent Cantet won the 2008 Palme d'Or for THE CLASS, but he turned in his best work seven years earlier with this depressingly relevant tale. From my 2001 AICN review: "Vincent (Aurelien Recoing) is a dedicated white-collar drone, forever on the road, traveling from one crucial business meeting to another, while keeping in touch with his family via cell phone, calling only to inform them that something else has come up, and that he won’t be home as planned. This is all a facade. In reality, Vincent lost his job several months ago, due precisely to this kind of itinerant behavior born out of a disaffection with a crushingly dull and depressingly pointless middle management position. Strangely, though, Vincent, rather than following up on job leads from a former co-worker, relishes his newfound freedom, driving aimlessly through the French countryside, and sleeping in his car rather than returning home, where his unavoidable financial responsibility to his family will surely intrude upon his semi-blissful existence.

There are probably thousands of Vincent’s out there – men and women stuck in that brutal middle-management loop with no sense of escape, and little self-worth. It is Cantet’s greatest triumph that he gives their heretofore satirized predicament a sobering, mournful voice."

61. GRINDHOUSE (2007, w. & d. Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "I'm probably grading Grindhouse on the experience of watching it at the New Beverly opening night, but this is my list, and I'll curve how I want to. Though I would never hail Planet Terror or Death Proof as masterpieces in their own right (not even Tarantino's extended cut of the latter, which inexplicably spoils Stuntman Mike's exquisite, over-the-shoulder introduction), mashed together with three lovingly crafted faux-trailers (and one disappointing display of onanism), they were pure moviegoing bliss. Did it help that I was knocking back smuggled-in Stone IPA's throughout the three-hour running time? Absolutely. Is that part of the grindhouse experience? Well, the boozing is; the relatively high-end taste for beer... not so much. But Grindhouse qualifies as epicurean trash, so why not wallow extravagantly?"

While I understand why the Weinstein's broke up the party when this thing grossed four dollars during its initial release, now that they've had a couple of years to recoup, it's time to give us us three-hour, unified cut of GRINDHOUSE.

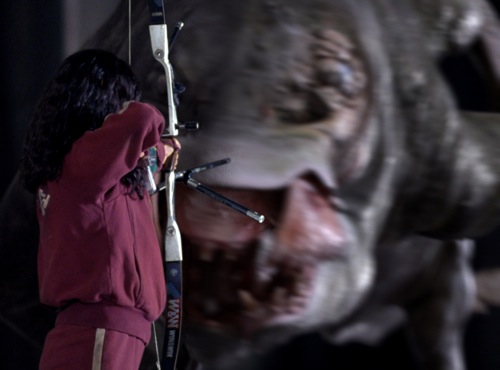

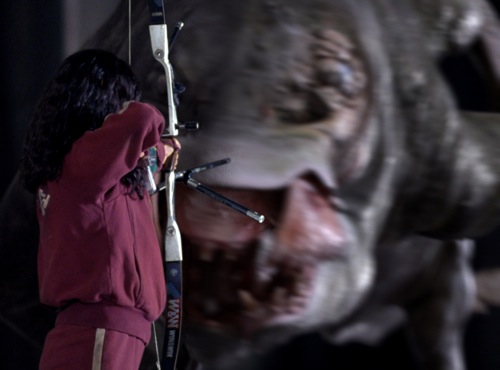

60. THE HOST (2006, d. Bong Joon-ho, w. Bong Joon-ho, Baek Chul-hyun and Ha Won-jun)

A heartwarming family dramedy about a giant sea monster that terrorizes Seoul as payback for a U.S. Army surgeon's careless disposal of formaldehyde.

THE HOST is a fearless melding of genres that never feels like its paying homage to one film in particular; it's also a perturbed critique of America's meddlesome involvement in the country. But it's mostly just an expertly-crafted monster movie from one of the most uniquely gifted filmmakers in the world.

59. TSOTSI (2005, w. & d. Gavin Hood)

From my Best of 2005 list for Collider: "How to account for a film that initially taps into the lurid exhilaration of City of God only to slam home with the moral authority of To Kill a Mockingbird? Three months after watching the film, I still don’t know much about Gavin Hood, so let’s start with Athol Fugard, the internationally renowned South African playwright on whose only novel the movie is based. The story is very simple: an unfeeling thug (a revelatory performance by Presley Chweneyage) shoots a middle class Johannesburg woman in the midst of a car jacking only to find a mile or two into his getaway that he has inadvertently kidnapped her infant child. While the parents enlist the unenthusiastic authorities to scour the shantytown for their baby, Tsotsi, not enough of a monster to cold bloodedly murder a defenseless newborn, ineptly tries to provide for the child if only to stop it from crying, and, in the process, backs away from the abyss toward which he’s been swaggering most of his life for lack of a better option.

[TSOTSI] is a timeless parable that captivates, enlightens and encourages us to better understand our fellow man no matter how far he’s fallen. And it does this without lecturing, condescending or pitying. Impossible."

And then Hood made RENDITION and WOLVERINE. Good for his bank account; bad for his art. Come back to us, Gavin.

58. HERO (2002, d. Zhang Yimou, w. Zhang, Li Feng and Wang Bin)

Zhang Yimou's high-minded answer to Ang Lee's CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON might have some uncomfortable nationalistic undercurrents, but they've never hindered my enjoyment of this gorgeously-shot film. Ching Siu-Tung's exquisite fight choreography and Christopher Doyle's sumptuous cinematography (abetted by Huo Tingxiao and Yi Zhenzhou's production design) combine to make HERO the most stylish and emotionally fulfilling martial arts picture ever produced.

57. BURN AFTER READING (2008, w & d. Joel and Ethan Coen)

From my 2008 review for AICN: "Joel and Ethan Coen's BURN AFTER READING opens with what appears to be a spy satellite's view of a computer-generated Earth. I think. Perhaps it's a model. Whatever it is, it's laughably fake, which means it's a detail the Coens really want you to notice. That this artificiality is accompanied by a bombastic Carter Burwell cue seemingly swiped from John Landis's SPIES LIKE US only serves to heighten the onrushing sense of parody; and as the camera comes crashing down through the fake clouds toward a fake United States and through the fake roof of a fake building in fake Langley, Virginia to reveal real CIA desk jockeys doing really stupid shit, your only response is to put your guard down and let the Coens enjoy their spirited, if inconsequential, NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN victory lap. Visually, they've just told you they're up to nothin' but funnin', right?

It's survival of the pettiest, and it's telling that the only person who achieves their objective is the one most hellbent on their own self-interest. But then the Coens' camera retreats from fake Langley, back through the fake clouds and out into the vast expanses of fake space, and we're reminded that people just don't get away with such things in our universe. It sure is swell to live in a world where justice prevails."

56. OLDBOY (2003, d. Chan-wook Park, w. Park, Jo-yun Hwang, Chun-hyeong Lim and Joon-hyung Lim)

The highlight of Butt-Numb-A-Thon V, this bizarro revenge yarn is Chan-wook Park at his most ferociously inspired. Considering Oh Dae-su's prolonged isolation and subsequent rough re-adjustment to regular society, I've always viewed OLDBOY as something of a metaphor for the still-unresolved North Korea-South Korea predicament. But it's so crazily over-plotted that any kind of thematic significance is secondary to the visceral pleasure of watching Oh Dae-su fuck up nearly everything and everyone in his path. First and foremost, this is an audience picture. Nothing wrong with that - not when it's this skillfully done.

55. MUNICH (2005, d. Steven Spielberg, w. Tony Kushner and Eric Roth)

From my Best of 2005 list for Collider: Steven Spielberg’s A Brief History of Revenge. Depicting the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre as the starting point of the modern Palestinian terrorism, Spielberg laments the downward spiral of violence even as he allows that the notion of inaction is patently absurd. Embedded in a breathtakingly assured suspense film that’s as masterful as the best paranoid thrillers of the 1970’s is the unsettling idea that civilization’s capitulation to bloodlust effectively destroyed (or, as some might say, exposed as a lie) the global pretense to morality celebrated after the Allied victory in World War II, ending with a coup de cinema in the picture’s final pan down the island of Manhattan. By utilizing the shadowy methods of the dispossessed as a means of squaring the dispute only begets more atrocities on both sides, and Spielberg pays his audience the compliment of being even-handed, which has been misconstrued by obfuscators on the right as “moral relativism”. There is a discussion to be had on the deploying of factually sketchy events to drive the point home, but dramatic license is hardly synonymous with dishonesty."

54. THE PIANIST (d. Roman Polanski, w. Ronald Harwood)

From my Best of 2002 list for AICN: "An unflinching, unsentimental survivor’s tale of the Holocaust that is ultimately more exhausting than profound. What lingers most in memory is Adrian Brody’s haunting central performance as a man with barely enough strength to endure."

I don't know why I was so dismissive of Roman Polanski's film back in '02, but it's now (correctly) regarded as a late-career triumph for the embattled director. THE PIANIST is a harrowing experience that contrasts jarringly with the saintly-survivor view of SCHINDLER'S LIST; talent, luck and compromise are essential, while decency is a potentially fatal luxury.

53. INTO THE WILD (w. & d. Sean Penn)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "Sean Penn always seemed on the verge of being a great filmmaker; it was just a matter of wedding his penchant for emotionally unsettled characters to material that wasn't too downbeat. So leave it to Penn to find the inspirational side to trekking off into the Alaskan wilderness and starving to death. This is, of course, a flippant way of saying that Penn personalized Jon Krakauer's fascinating tome about Christopher McCandless's ill-fated quest for a transformative rite of passage. Whereas Krakauer emphasized the cautionary (while trying to defend McCandless's folly), Penn celebrates the brave, kinda-crazy, off-the-grid romance McCandless indulged as a means of rejecting the prescribed path to professionalism set down by his no-nonsense father. It was a selfish journey to be sure, but Penn portrays it as a sacrifice for all those who would never stray from the expected and venture off into the unknown."

52. MASTER AND COMMANDER: THE FAR SIDE OF THE WORLD (2003, d. Peter Weir, w. Weir and John Collee)

From my 2004 DVD Journal review: "It's impossible to imagine [Patrick O'Brian's] books being brought to life by anyone else but Weir, whose ongoing fascination with outsiders entering strange cultures is an ideal fit for the project. Unlike his previous films, however, the characters are all completely at home in their world; it's the audience who's the outsider. When one understands this, that opening, dimly lit tour of the [H.M.S. Surprise], scored to little more than the ambient sound of a working ship at sea, makes perfect sense. It's the moment of enchantment through which Weir works his customary magic, and it lingers undisturbed for a wonderful couple of hours until the closing credits finally breaks the spell. It's as good, as stirring, and as pleasurable as time spent under a reading light with O'Brian's prose."

Tom Rothman, the much-maligned Fox chairman, deserves an enormous amount of credit for getting this (financially unsuccessful) film made. So thank you, Tom, for this immersive, one-of-a-kind cinematic experience. There, I said it.

51. MULHOLLAND DR. (w. & d. David Lynch)

From my 2001 review for AICN: Technically, the film is a marvel. Peter Demming’s cinematography has an absurdly soft glow in daylight, but his most notable achievement is the way he renders darkness as an inescapably malevolent character. No one been this at home in the shadows since Gordon Willis. Meanwhile, Lynch lends this darkness a kind of voice through his sound design; a low, ominous rumble accompanies even the quietest moments, and seems ever on the verge of an abrupt crescendo to a roar. Consider yourself forewarned that Lynch is more than happy to kick the volume up to some frighteningly high-decibel levels (it’s his best use of sound since his perennially underrated TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME).

Yes, MULHOLLAND DRIVE is not for all tastes; it’ll be anathema for hard-core narrative junkies, and will send the faint-of-heart scrambling for the exits within the first ten minutes. For everyone else, it’s classic Lynch – perversely funny and unspeakably terrifying in near equal measures. To be precise, a masterpiece."

Halfway through. Apologies for relying so heavily on my old reviews for this batch, but it's been a very busy week. I'll be hard at work this weekend writing up as many fresh capsules as possible for the final fifty - which will be posted by Wednesday morning at the latest.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks

73. THE FOUNTAIN (w. & d. Darren Aronofsky)

Darren Aronofsky's madly ambitious film about the quest to not die, and to not let anyone we love die, leads with its soul and succeeds because the writer-director never once tries to over-intellectualize the experience. He just wants to break our heart. In trying together three not-too-disparate stories - about a conquistador's search for the tree of life, a cancer researcher's attempts to disappear his wife's brain tumor, and a future dude's intergalactic journey with a dying tree and his deceased wife's ghost - Aronofsky evokes deep sadness as we have our silly hopes crushed once again. Life and love are fleeting, loss is inevitable, and there ain't a damn thing we can do about it.

THE FOUNTAIN is the heartfelt flip-side to the oppressive nihilism of REQUIEM FOR A DREAM. It's also Aronofsky's finest film to date. Sadly, Clint Mansell's lovely score is now being used to sell insipid Hollywood product. If you love this film as much as I do, this cue should wreck you every time you hear it:

72. UNITED 93 (2006, w. & d. Paul Greengrass)

From my 2006 Collider review: “As for unflinching, documentary-style recreations of actual events, United 93 is as relentless as Gillo Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers (though, obviously, much more contained and much, much less political). Greengrass has no intention of sparing the audience any of the ugliness that transpired on the ill-fated flight, particularly in the grisly third act, and his ferociousness will certainly prove too much for more sensitive viewers. As someone who viewed the smoldering Twin Towers from the twenty-sixth floor of the MetLife Building in midtown Manhattan, and, like so many other New Yorkers, glumly went through the motions for a week or two following the attack on our city, I often wondered what the hell I was doing in the theater. Aside from bearing witness to Greengrass’s maturation as a filmmaker (and this is easily his most accomplished work yet), I spent most of the moments prior to the start of the film trying to figure out why I’d bothered.

...[But] that’s why United 93 needs to exist, and why I think it will become an important, widely-seen documenting of the day everything changed for Americans. We need to remember the heroic deeds in the early hours of 9/11, and, for the sake of unity, we don’t necessarily need politics to enter into it. That said, the apolitical nature of Greengrass’s film may wind up rendering it a little quaint once writers and directors grow a bit bolder in tackling the subject. Rossellini’s Open City and Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers still resonate today because they have a contentious point of view; though far from timid, the objective United 93 is ripe to eventually get overshadowed by more opinionated works.”

Even if those works come along in the next decade, UNITED 93 will always be a chilling and boldly unsentimental reminder that that could've been you or me on that plane. Several years after its theatrical release, this film now feels incapable of being overshadowed.

71. THE HOLY GIRL (2004, w. & d. Lucretia Martel)

A vast improvement over her first movie, LA CIENAGA (which felt like a study of human beings struck inactive by extreme humidity), THE HOLY GIRL finds Lucretia Martel figuring it out as she goes along - both as a director and a storyteller. Whereas little seemed to coalesce by the end of LA CIENAGA (thematically or narratively), everything sort of slides into place here, and what at first threatens to be a morality play about a middle-aged doctor's improper contact with a teenage girl (brought on by, what else, a theremin) gradually turns into a mediation on the absence of innocence. At least, that's my take. Martel's film is generously open-ended - even though it's also put together with a deceptive precision. She's a major talent. (And I must shamefully admit that I have yet to see THE HEADLESS WOMAN.)

70. BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN (2005, d. Ang Lee, w. Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana)

From my Best of 2005 for Collider: "When Ang Lee was told BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN, which utilizes young actors to tell a multi-generational tale of societal discovery, could be viewed as “GIANT turned inward”, he smiled and shot back, “Or GIANT turned outward”. Such irreverence may have been unexpected after the heartbreak of his lushly romantic epic, but that puckish comment underscores the wry humanity present in all of Lee’s films. Sure, he tackles weighty topics with occasionally tragic outcomes, but you can’t get to the wounded core of your characters without a touch of levity, which is abundant in Jack and Ennis’s gradual, unexpected courtship at the outset. Working from a fantastic script by Larry McMurty and Diana Ossana, Lee avoids the pitfalls of obviousness at every turn, right up to the pulverizing finale where the emotional understatement of all that’s come before pays off in well-earned tears - at which point BROKEBACK equals the impact of its fifty-year-old progenitor with a far more economical use of screen time. (It’s also important to note that, like George Stevens, Lee is not revising the Western genre; he's seeking to redefine an archetype much bigger than its filmic representation. In other words, comparisons to other Westerns are awfully limiting.)

I had no idea how apt those GIANT comparisons would be three years ago. And even though we got more, quantity-wise, from Ledger, the thought that he exited right at the moment he was coming alive as a performer is anything but comforting.

69. WALL-E (2008, d. Andrew Stanton, w. Stanton and Jim Reardon)

From my 2008 AICN review: Despite the gentle, MODERN TIMES-inspired satire, "true love" is the motor of this story. It's a lovely gesture, and it makes me smile, but there's a part of me that wonders whether we'd be referring to Stanton's film as genuflectingly brilliant if he left WALL-E's memory wiped at the end. Most all-ages classics require some semblance of sacrifice: we assume Elliott will never see E.T. again, whilst another noggin-knockin' trip to Oz would probably leave Dorothy talking like Leon Spinks. But after a few we-know-you're-not-going-there scares, WALL-E gets rebooted and is shipshape once again (like Uhura post-"The Changeling").

On second thought, since I've made a similar argument in defense of Tom Cruise's kid "miraculously" returning at the end of Spielberg's WAR OF THE WORLDS, I'm going to be consistent and say the ending is exactly what it needs to be: WALL-E lays out for "the needs of the many", and he is duly rewarded by not being reduced to a memory-wiped droid. This doesn't mean WALL-E is now "genuflectingly brilliant", but it is top-shelf Pixar - and that's more than good enough to place here.

68. SUPERBAD (d. Greg Mottola, w. Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen)

From my Best of 2007 list from CHUD: "The return of Greg Mottola (director of the underrated and underseen The Daytrippers), the debut of Christopher Mintz-Plasse (the Anthony Michael Hall of his generation if he's unlucky, which I don't think he'll be) and more stellar Apatow. Everyone jokes that there's going to be a backlash at some point (maybe the box office failure of Walk Hard is an indication of this), but why? As long as the company keeps expanding, and the leads keep changing (though Seth Rogen is a bona fide superstar, and could do with a movie a year), what's there to resent besides success? In a way, I think Superbad points the way forward: it's the Apatow aesthetic in the hands of a filmmaker with a completely different skill set. It's also (in its theatrical incarnation) the tightest of the Apatow flicks thus far."

Two years later, it still is. Though the comedy gets pretty broad at times, SUPERBAD effortlessly exudes that universal, wild-night-out feel that made DAZED AND CONFUSED an instant classic. This is largely the doing of Mottola, who followed this up with the ADVENTURELAND, a bittersweet evocation of post-college ennui that deserves a much wider audience. I love both films, but SUPERBAD hits so many highs (Cera enchanting a roomful of cokeheads with his frightened rendition of "These Eyes"; Carla Gallo leaving her mark on Hill's pants; that nervous/giddy moment before Mintz-Plasse empties Hader's service revolver) that it just barely gets the nod.

67. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE (2009, d. Spike Jonze, w. Jonze and Dave Eggers)

A film that could very well move up this list as the years pile on.

I haven't gone back since my first viewing, but the final scene - where Keener falls asleep watching a safely-returned Max scarf down his dinner without a care in the world - hits me hard. Though we didn't realize it at the time, we all participated in those moments - where our mothers found solace in us just being happy and young and theirs. And you get the sense that Keener hangs on to consciousness for as long as she can because she knows how fleeting this all is. In a few years time, Max will enter middle-school, and this bond will dissolve. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE strikes many resonant, melancholy chords, but in the end, it just made me miss being a kid for my mom. And that's why it made me sad.

I also think the final shot of ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND is a complete downer, so if I'm alone in this reading, so be it.

From my 2009 AICN interview with Spike Jonze: "While WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE feels like a deeply personal film for Jonze, its depiction of a bratty kid run amok - and away to an island of moody monsters - is also incredibly inclusive. The specifics of Max's childhood may not resemble yours, but the highs and lows he experiences should be painfully familiar. No film has more perfectly captured what it feels like to be nine years old."

66. THE CONSTANT GARDENER (2005, d. Fernando Meirelles, w. Jeffrey Caine)

Beats the tar out of THE LITTLE DRUMMER GIRL. From my 2005 review for Collider: "It took a filmmaker as prodigiously talented as Fernando Meirelles to finally transfer John le Carré successfully to the screen, though his accomplishment reaches past the angry espionage of the novel to discover a doomed romanticism reminiscent of Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient. Borrowing that film’s lead (the great Ralph Fiennes), Meirelles has skillfully constructed a love story in which affection is not truly requited until both parties are murdered. Rachel Weisz’s Tessa Quayle hastens her death questing justice; Fiennes’s Justin Quayle brings about his by taking on Tessa’s cause after jealously investigating her possible infidelity. Justin’s a horrible sleuth, the meek antithesis of Harry Palmer, but Meirelles and le Carré aren’t after a rousing thriller in that mold. And though the movie brims with righteous indignation, it isn’t a political tract, either. What stays with you is the thought of Tessa and Justin reaching the same terminus alone."

65. LAKE OF FIRE (2007, d. Tony Kaye)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "I knew where I came down on the abortion issue before I saw Tony Kaye's Lake of Fire; afterwards... I was a lot less certain. An objective and exhaustive documentary examining both sides of this roiling, often violent debate, Kaye challenges our preconceived notions by juxtaposing the tired, talking-point spiel regurgitated by the rank-and-file with thoughtful analysis from journalists like Nat Hentoff (who skillfully, if not entirely persuasively, argues the inconsistency of being anti-death penalty and pro-choice). But don't mistake this for a talking heads affair; Kaye reminds us, with his brilliant black-and-white cinematography, that he's one of the most visually gifted filmmakers working today. He's also unflinching in his depiction of the actual process of abortion, the aftermath of which will surely be too much for most viewers. Sensationalism aside, Kaye's still made the most thorough and even-handed documentary on this deeply divisive subject."

64. TIME OF THE WOLF (2003, w. & d. Michael Haneke)

This unusually straightforward work from Michael Haneke is about a French family struggling to cope with the end of the world as we know it. Haneke skimps on the catastrophic particulars and instead focuses on the collapse of society - which has been depicted hundreds of times before, but rarely with this level of verisimilitude. Isabelle Huppert is sensational as the mother fighting to protect her children and maintain civility as the strangers they encounter gradually give in to their basest survival instincts. What's surprising here is Haneke's near-acknowledgment that order can be reimposed; inevitably, as long as the planet's not in a sere shambles or a pipin' hot ball of fire (hey there, Alex Proyas!), we will rebuild. This is the one Haneke film that helps you up after it knees you in the nuts.

63. KAIRO (2001, w. & d. Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Hands down the best J-horror film of the decade - so long as you're counting AUDITION as a 1999 release. Though its "gimmick" of spooky images being captured via webcams feels incredibly quaint nowadays, Kiyoshi Kurosawa's 2001 classic is still an impeccably-crafted, slow-burner of a ghost story. As with most films of this subgenre, the set pieces are pretty much the show (this fucker is an unrepentant nightmare machine), but there's an unexpected scale and thoughtfulness to Kurosawa's story that's more Romero than Shimizu. Unlike RINGU or JU-ON, repeat viewings are anything but a case of diminishing returns.

62. TIME OUT (2001, d. Laurent Cantet, w. Cantet and Robin Campillo)

Laurent Cantet won the 2008 Palme d'Or for THE CLASS, but he turned in his best work seven years earlier with this depressingly relevant tale. From my 2001 AICN review: "Vincent (Aurelien Recoing) is a dedicated white-collar drone, forever on the road, traveling from one crucial business meeting to another, while keeping in touch with his family via cell phone, calling only to inform them that something else has come up, and that he won’t be home as planned. This is all a facade. In reality, Vincent lost his job several months ago, due precisely to this kind of itinerant behavior born out of a disaffection with a crushingly dull and depressingly pointless middle management position. Strangely, though, Vincent, rather than following up on job leads from a former co-worker, relishes his newfound freedom, driving aimlessly through the French countryside, and sleeping in his car rather than returning home, where his unavoidable financial responsibility to his family will surely intrude upon his semi-blissful existence.

There are probably thousands of Vincent’s out there – men and women stuck in that brutal middle-management loop with no sense of escape, and little self-worth. It is Cantet’s greatest triumph that he gives their heretofore satirized predicament a sobering, mournful voice."

61. GRINDHOUSE (2007, w. & d. Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "I'm probably grading Grindhouse on the experience of watching it at the New Beverly opening night, but this is my list, and I'll curve how I want to. Though I would never hail Planet Terror or Death Proof as masterpieces in their own right (not even Tarantino's extended cut of the latter, which inexplicably spoils Stuntman Mike's exquisite, over-the-shoulder introduction), mashed together with three lovingly crafted faux-trailers (and one disappointing display of onanism), they were pure moviegoing bliss. Did it help that I was knocking back smuggled-in Stone IPA's throughout the three-hour running time? Absolutely. Is that part of the grindhouse experience? Well, the boozing is; the relatively high-end taste for beer... not so much. But Grindhouse qualifies as epicurean trash, so why not wallow extravagantly?"

While I understand why the Weinstein's broke up the party when this thing grossed four dollars during its initial release, now that they've had a couple of years to recoup, it's time to give us us three-hour, unified cut of GRINDHOUSE.

60. THE HOST (2006, d. Bong Joon-ho, w. Bong Joon-ho, Baek Chul-hyun and Ha Won-jun)

A heartwarming family dramedy about a giant sea monster that terrorizes Seoul as payback for a U.S. Army surgeon's careless disposal of formaldehyde.

THE HOST is a fearless melding of genres that never feels like its paying homage to one film in particular; it's also a perturbed critique of America's meddlesome involvement in the country. But it's mostly just an expertly-crafted monster movie from one of the most uniquely gifted filmmakers in the world.

59. TSOTSI (2005, w. & d. Gavin Hood)

From my Best of 2005 list for Collider: "How to account for a film that initially taps into the lurid exhilaration of City of God only to slam home with the moral authority of To Kill a Mockingbird? Three months after watching the film, I still don’t know much about Gavin Hood, so let’s start with Athol Fugard, the internationally renowned South African playwright on whose only novel the movie is based. The story is very simple: an unfeeling thug (a revelatory performance by Presley Chweneyage) shoots a middle class Johannesburg woman in the midst of a car jacking only to find a mile or two into his getaway that he has inadvertently kidnapped her infant child. While the parents enlist the unenthusiastic authorities to scour the shantytown for their baby, Tsotsi, not enough of a monster to cold bloodedly murder a defenseless newborn, ineptly tries to provide for the child if only to stop it from crying, and, in the process, backs away from the abyss toward which he’s been swaggering most of his life for lack of a better option.

[TSOTSI] is a timeless parable that captivates, enlightens and encourages us to better understand our fellow man no matter how far he’s fallen. And it does this without lecturing, condescending or pitying. Impossible."

And then Hood made RENDITION and WOLVERINE. Good for his bank account; bad for his art. Come back to us, Gavin.

58. HERO (2002, d. Zhang Yimou, w. Zhang, Li Feng and Wang Bin)

Zhang Yimou's high-minded answer to Ang Lee's CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON might have some uncomfortable nationalistic undercurrents, but they've never hindered my enjoyment of this gorgeously-shot film. Ching Siu-Tung's exquisite fight choreography and Christopher Doyle's sumptuous cinematography (abetted by Huo Tingxiao and Yi Zhenzhou's production design) combine to make HERO the most stylish and emotionally fulfilling martial arts picture ever produced.

57. BURN AFTER READING (2008, w & d. Joel and Ethan Coen)

From my 2008 review for AICN: "Joel and Ethan Coen's BURN AFTER READING opens with what appears to be a spy satellite's view of a computer-generated Earth. I think. Perhaps it's a model. Whatever it is, it's laughably fake, which means it's a detail the Coens really want you to notice. That this artificiality is accompanied by a bombastic Carter Burwell cue seemingly swiped from John Landis's SPIES LIKE US only serves to heighten the onrushing sense of parody; and as the camera comes crashing down through the fake clouds toward a fake United States and through the fake roof of a fake building in fake Langley, Virginia to reveal real CIA desk jockeys doing really stupid shit, your only response is to put your guard down and let the Coens enjoy their spirited, if inconsequential, NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN victory lap. Visually, they've just told you they're up to nothin' but funnin', right?

It's survival of the pettiest, and it's telling that the only person who achieves their objective is the one most hellbent on their own self-interest. But then the Coens' camera retreats from fake Langley, back through the fake clouds and out into the vast expanses of fake space, and we're reminded that people just don't get away with such things in our universe. It sure is swell to live in a world where justice prevails."

56. OLDBOY (2003, d. Chan-wook Park, w. Park, Jo-yun Hwang, Chun-hyeong Lim and Joon-hyung Lim)

The highlight of Butt-Numb-A-Thon V, this bizarro revenge yarn is Chan-wook Park at his most ferociously inspired. Considering Oh Dae-su's prolonged isolation and subsequent rough re-adjustment to regular society, I've always viewed OLDBOY as something of a metaphor for the still-unresolved North Korea-South Korea predicament. But it's so crazily over-plotted that any kind of thematic significance is secondary to the visceral pleasure of watching Oh Dae-su fuck up nearly everything and everyone in his path. First and foremost, this is an audience picture. Nothing wrong with that - not when it's this skillfully done.

55. MUNICH (2005, d. Steven Spielberg, w. Tony Kushner and Eric Roth)

From my Best of 2005 list for Collider: Steven Spielberg’s A Brief History of Revenge. Depicting the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre as the starting point of the modern Palestinian terrorism, Spielberg laments the downward spiral of violence even as he allows that the notion of inaction is patently absurd. Embedded in a breathtakingly assured suspense film that’s as masterful as the best paranoid thrillers of the 1970’s is the unsettling idea that civilization’s capitulation to bloodlust effectively destroyed (or, as some might say, exposed as a lie) the global pretense to morality celebrated after the Allied victory in World War II, ending with a coup de cinema in the picture’s final pan down the island of Manhattan. By utilizing the shadowy methods of the dispossessed as a means of squaring the dispute only begets more atrocities on both sides, and Spielberg pays his audience the compliment of being even-handed, which has been misconstrued by obfuscators on the right as “moral relativism”. There is a discussion to be had on the deploying of factually sketchy events to drive the point home, but dramatic license is hardly synonymous with dishonesty."

54. THE PIANIST (d. Roman Polanski, w. Ronald Harwood)

From my Best of 2002 list for AICN: "An unflinching, unsentimental survivor’s tale of the Holocaust that is ultimately more exhausting than profound. What lingers most in memory is Adrian Brody’s haunting central performance as a man with barely enough strength to endure."

I don't know why I was so dismissive of Roman Polanski's film back in '02, but it's now (correctly) regarded as a late-career triumph for the embattled director. THE PIANIST is a harrowing experience that contrasts jarringly with the saintly-survivor view of SCHINDLER'S LIST; talent, luck and compromise are essential, while decency is a potentially fatal luxury.

53. INTO THE WILD (w. & d. Sean Penn)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "Sean Penn always seemed on the verge of being a great filmmaker; it was just a matter of wedding his penchant for emotionally unsettled characters to material that wasn't too downbeat. So leave it to Penn to find the inspirational side to trekking off into the Alaskan wilderness and starving to death. This is, of course, a flippant way of saying that Penn personalized Jon Krakauer's fascinating tome about Christopher McCandless's ill-fated quest for a transformative rite of passage. Whereas Krakauer emphasized the cautionary (while trying to defend McCandless's folly), Penn celebrates the brave, kinda-crazy, off-the-grid romance McCandless indulged as a means of rejecting the prescribed path to professionalism set down by his no-nonsense father. It was a selfish journey to be sure, but Penn portrays it as a sacrifice for all those who would never stray from the expected and venture off into the unknown."

52. MASTER AND COMMANDER: THE FAR SIDE OF THE WORLD (2003, d. Peter Weir, w. Weir and John Collee)

From my 2004 DVD Journal review: "It's impossible to imagine [Patrick O'Brian's] books being brought to life by anyone else but Weir, whose ongoing fascination with outsiders entering strange cultures is an ideal fit for the project. Unlike his previous films, however, the characters are all completely at home in their world; it's the audience who's the outsider. When one understands this, that opening, dimly lit tour of the [H.M.S. Surprise], scored to little more than the ambient sound of a working ship at sea, makes perfect sense. It's the moment of enchantment through which Weir works his customary magic, and it lingers undisturbed for a wonderful couple of hours until the closing credits finally breaks the spell. It's as good, as stirring, and as pleasurable as time spent under a reading light with O'Brian's prose."

Tom Rothman, the much-maligned Fox chairman, deserves an enormous amount of credit for getting this (financially unsuccessful) film made. So thank you, Tom, for this immersive, one-of-a-kind cinematic experience. There, I said it.

51. MULHOLLAND DR. (w. & d. David Lynch)

From my 2001 review for AICN: Technically, the film is a marvel. Peter Demming’s cinematography has an absurdly soft glow in daylight, but his most notable achievement is the way he renders darkness as an inescapably malevolent character. No one been this at home in the shadows since Gordon Willis. Meanwhile, Lynch lends this darkness a kind of voice through his sound design; a low, ominous rumble accompanies even the quietest moments, and seems ever on the verge of an abrupt crescendo to a roar. Consider yourself forewarned that Lynch is more than happy to kick the volume up to some frighteningly high-decibel levels (it’s his best use of sound since his perennially underrated TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME).

Yes, MULHOLLAND DRIVE is not for all tastes; it’ll be anathema for hard-core narrative junkies, and will send the faint-of-heart scrambling for the exits within the first ten minutes. For everyone else, it’s classic Lynch – perversely funny and unspeakably terrifying in near equal measures. To be precise, a masterpiece."

Halfway through. Apologies for relying so heavily on my old reviews for this batch, but it's been a very busy week. I'll be hard at work this weekend writing up as many fresh capsules as possible for the final fifty - which will be posted by Wednesday morning at the latest.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks

71. THE HOLY GIRL (2004, w. & d. Lucretia Martel)

A vast improvement over her first movie, LA CIENAGA (which felt like a study of human beings struck inactive by extreme humidity), THE HOLY GIRL finds Lucretia Martel figuring it out as she goes along - both as a director and a storyteller. Whereas little seemed to coalesce by the end of LA CIENAGA (thematically or narratively), everything sort of slides into place here, and what at first threatens to be a morality play about a middle-aged doctor's improper contact with a teenage girl (brought on by, what else, a theremin) gradually turns into a mediation on the absence of innocence. At least, that's my take. Martel's film is generously open-ended - even though it's also put together with a deceptive precision. She's a major talent. (And I must shamefully admit that I have yet to see THE HEADLESS WOMAN.)

70. BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN (2005, d. Ang Lee, w. Larry McMurtry and Diana Ossana)

From my Best of 2005 for Collider: "When Ang Lee was told BROKEBACK MOUNTAIN, which utilizes young actors to tell a multi-generational tale of societal discovery, could be viewed as “GIANT turned inward”, he smiled and shot back, “Or GIANT turned outward”. Such irreverence may have been unexpected after the heartbreak of his lushly romantic epic, but that puckish comment underscores the wry humanity present in all of Lee’s films. Sure, he tackles weighty topics with occasionally tragic outcomes, but you can’t get to the wounded core of your characters without a touch of levity, which is abundant in Jack and Ennis’s gradual, unexpected courtship at the outset. Working from a fantastic script by Larry McMurty and Diana Ossana, Lee avoids the pitfalls of obviousness at every turn, right up to the pulverizing finale where the emotional understatement of all that’s come before pays off in well-earned tears - at which point BROKEBACK equals the impact of its fifty-year-old progenitor with a far more economical use of screen time. (It’s also important to note that, like George Stevens, Lee is not revising the Western genre; he's seeking to redefine an archetype much bigger than its filmic representation. In other words, comparisons to other Westerns are awfully limiting.)

I had no idea how apt those GIANT comparisons would be three years ago. And even though we got more, quantity-wise, from Ledger, the thought that he exited right at the moment he was coming alive as a performer is anything but comforting.

69. WALL-E (2008, d. Andrew Stanton, w. Stanton and Jim Reardon)

From my 2008 AICN review: Despite the gentle, MODERN TIMES-inspired satire, "true love" is the motor of this story. It's a lovely gesture, and it makes me smile, but there's a part of me that wonders whether we'd be referring to Stanton's film as genuflectingly brilliant if he left WALL-E's memory wiped at the end. Most all-ages classics require some semblance of sacrifice: we assume Elliott will never see E.T. again, whilst another noggin-knockin' trip to Oz would probably leave Dorothy talking like Leon Spinks. But after a few we-know-you're-not-going-there scares, WALL-E gets rebooted and is shipshape once again (like Uhura post-"The Changeling").

On second thought, since I've made a similar argument in defense of Tom Cruise's kid "miraculously" returning at the end of Spielberg's WAR OF THE WORLDS, I'm going to be consistent and say the ending is exactly what it needs to be: WALL-E lays out for "the needs of the many", and he is duly rewarded by not being reduced to a memory-wiped droid. This doesn't mean WALL-E is now "genuflectingly brilliant", but it is top-shelf Pixar - and that's more than good enough to place here.

68. SUPERBAD (d. Greg Mottola, w. Evan Goldberg and Seth Rogen)

From my Best of 2007 list from CHUD: "The return of Greg Mottola (director of the underrated and underseen The Daytrippers), the debut of Christopher Mintz-Plasse (the Anthony Michael Hall of his generation if he's unlucky, which I don't think he'll be) and more stellar Apatow. Everyone jokes that there's going to be a backlash at some point (maybe the box office failure of Walk Hard is an indication of this), but why? As long as the company keeps expanding, and the leads keep changing (though Seth Rogen is a bona fide superstar, and could do with a movie a year), what's there to resent besides success? In a way, I think Superbad points the way forward: it's the Apatow aesthetic in the hands of a filmmaker with a completely different skill set. It's also (in its theatrical incarnation) the tightest of the Apatow flicks thus far."

Two years later, it still is. Though the comedy gets pretty broad at times, SUPERBAD effortlessly exudes that universal, wild-night-out feel that made DAZED AND CONFUSED an instant classic. This is largely the doing of Mottola, who followed this up with the ADVENTURELAND, a bittersweet evocation of post-college ennui that deserves a much wider audience. I love both films, but SUPERBAD hits so many highs (Cera enchanting a roomful of cokeheads with his frightened rendition of "These Eyes"; Carla Gallo leaving her mark on Hill's pants; that nervous/giddy moment before Mintz-Plasse empties Hader's service revolver) that it just barely gets the nod.

67. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE (2009, d. Spike Jonze, w. Jonze and Dave Eggers)

A film that could very well move up this list as the years pile on.

I haven't gone back since my first viewing, but the final scene - where Keener falls asleep watching a safely-returned Max scarf down his dinner without a care in the world - hits me hard. Though we didn't realize it at the time, we all participated in those moments - where our mothers found solace in us just being happy and young and theirs. And you get the sense that Keener hangs on to consciousness for as long as she can because she knows how fleeting this all is. In a few years time, Max will enter middle-school, and this bond will dissolve. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE strikes many resonant, melancholy chords, but in the end, it just made me miss being a kid for my mom. And that's why it made me sad.

I also think the final shot of ETERNAL SUNSHINE OF THE SPOTLESS MIND is a complete downer, so if I'm alone in this reading, so be it.

From my 2009 AICN interview with Spike Jonze: "While WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE feels like a deeply personal film for Jonze, its depiction of a bratty kid run amok - and away to an island of moody monsters - is also incredibly inclusive. The specifics of Max's childhood may not resemble yours, but the highs and lows he experiences should be painfully familiar. No film has more perfectly captured what it feels like to be nine years old."

66. THE CONSTANT GARDENER (2005, d. Fernando Meirelles, w. Jeffrey Caine)

Beats the tar out of THE LITTLE DRUMMER GIRL. From my 2005 review for Collider: "It took a filmmaker as prodigiously talented as Fernando Meirelles to finally transfer John le Carré successfully to the screen, though his accomplishment reaches past the angry espionage of the novel to discover a doomed romanticism reminiscent of Anthony Minghella’s The English Patient. Borrowing that film’s lead (the great Ralph Fiennes), Meirelles has skillfully constructed a love story in which affection is not truly requited until both parties are murdered. Rachel Weisz’s Tessa Quayle hastens her death questing justice; Fiennes’s Justin Quayle brings about his by taking on Tessa’s cause after jealously investigating her possible infidelity. Justin’s a horrible sleuth, the meek antithesis of Harry Palmer, but Meirelles and le Carré aren’t after a rousing thriller in that mold. And though the movie brims with righteous indignation, it isn’t a political tract, either. What stays with you is the thought of Tessa and Justin reaching the same terminus alone."

65. LAKE OF FIRE (2007, d. Tony Kaye)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "I knew where I came down on the abortion issue before I saw Tony Kaye's Lake of Fire; afterwards... I was a lot less certain. An objective and exhaustive documentary examining both sides of this roiling, often violent debate, Kaye challenges our preconceived notions by juxtaposing the tired, talking-point spiel regurgitated by the rank-and-file with thoughtful analysis from journalists like Nat Hentoff (who skillfully, if not entirely persuasively, argues the inconsistency of being anti-death penalty and pro-choice). But don't mistake this for a talking heads affair; Kaye reminds us, with his brilliant black-and-white cinematography, that he's one of the most visually gifted filmmakers working today. He's also unflinching in his depiction of the actual process of abortion, the aftermath of which will surely be too much for most viewers. Sensationalism aside, Kaye's still made the most thorough and even-handed documentary on this deeply divisive subject."

64. TIME OF THE WOLF (2003, w. & d. Michael Haneke)

This unusually straightforward work from Michael Haneke is about a French family struggling to cope with the end of the world as we know it. Haneke skimps on the catastrophic particulars and instead focuses on the collapse of society - which has been depicted hundreds of times before, but rarely with this level of verisimilitude. Isabelle Huppert is sensational as the mother fighting to protect her children and maintain civility as the strangers they encounter gradually give in to their basest survival instincts. What's surprising here is Haneke's near-acknowledgment that order can be reimposed; inevitably, as long as the planet's not in a sere shambles or a pipin' hot ball of fire (hey there, Alex Proyas!), we will rebuild. This is the one Haneke film that helps you up after it knees you in the nuts.

63. KAIRO (2001, w. & d. Kiyoshi Kurosawa)

Hands down the best J-horror film of the decade - so long as you're counting AUDITION as a 1999 release. Though its "gimmick" of spooky images being captured via webcams feels incredibly quaint nowadays, Kiyoshi Kurosawa's 2001 classic is still an impeccably-crafted, slow-burner of a ghost story. As with most films of this subgenre, the set pieces are pretty much the show (this fucker is an unrepentant nightmare machine), but there's an unexpected scale and thoughtfulness to Kurosawa's story that's more Romero than Shimizu. Unlike RINGU or JU-ON, repeat viewings are anything but a case of diminishing returns.

62. TIME OUT (2001, d. Laurent Cantet, w. Cantet and Robin Campillo)

Laurent Cantet won the 2008 Palme d'Or for THE CLASS, but he turned in his best work seven years earlier with this depressingly relevant tale. From my 2001 AICN review: "Vincent (Aurelien Recoing) is a dedicated white-collar drone, forever on the road, traveling from one crucial business meeting to another, while keeping in touch with his family via cell phone, calling only to inform them that something else has come up, and that he won’t be home as planned. This is all a facade. In reality, Vincent lost his job several months ago, due precisely to this kind of itinerant behavior born out of a disaffection with a crushingly dull and depressingly pointless middle management position. Strangely, though, Vincent, rather than following up on job leads from a former co-worker, relishes his newfound freedom, driving aimlessly through the French countryside, and sleeping in his car rather than returning home, where his unavoidable financial responsibility to his family will surely intrude upon his semi-blissful existence.

There are probably thousands of Vincent’s out there – men and women stuck in that brutal middle-management loop with no sense of escape, and little self-worth. It is Cantet’s greatest triumph that he gives their heretofore satirized predicament a sobering, mournful voice."

61. GRINDHOUSE (2007, w. & d. Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "I'm probably grading Grindhouse on the experience of watching it at the New Beverly opening night, but this is my list, and I'll curve how I want to. Though I would never hail Planet Terror or Death Proof as masterpieces in their own right (not even Tarantino's extended cut of the latter, which inexplicably spoils Stuntman Mike's exquisite, over-the-shoulder introduction), mashed together with three lovingly crafted faux-trailers (and one disappointing display of onanism), they were pure moviegoing bliss. Did it help that I was knocking back smuggled-in Stone IPA's throughout the three-hour running time? Absolutely. Is that part of the grindhouse experience? Well, the boozing is; the relatively high-end taste for beer... not so much. But Grindhouse qualifies as epicurean trash, so why not wallow extravagantly?"

While I understand why the Weinstein's broke up the party when this thing grossed four dollars during its initial release, now that they've had a couple of years to recoup, it's time to give us us three-hour, unified cut of GRINDHOUSE.

60. THE HOST (2006, d. Bong Joon-ho, w. Bong Joon-ho, Baek Chul-hyun and Ha Won-jun)

A heartwarming family dramedy about a giant sea monster that terrorizes Seoul as payback for a U.S. Army surgeon's careless disposal of formaldehyde.

THE HOST is a fearless melding of genres that never feels like its paying homage to one film in particular; it's also a perturbed critique of America's meddlesome involvement in the country. But it's mostly just an expertly-crafted monster movie from one of the most uniquely gifted filmmakers in the world.

59. TSOTSI (2005, w. & d. Gavin Hood)

From my Best of 2005 list for Collider: "How to account for a film that initially taps into the lurid exhilaration of City of God only to slam home with the moral authority of To Kill a Mockingbird? Three months after watching the film, I still don’t know much about Gavin Hood, so let’s start with Athol Fugard, the internationally renowned South African playwright on whose only novel the movie is based. The story is very simple: an unfeeling thug (a revelatory performance by Presley Chweneyage) shoots a middle class Johannesburg woman in the midst of a car jacking only to find a mile or two into his getaway that he has inadvertently kidnapped her infant child. While the parents enlist the unenthusiastic authorities to scour the shantytown for their baby, Tsotsi, not enough of a monster to cold bloodedly murder a defenseless newborn, ineptly tries to provide for the child if only to stop it from crying, and, in the process, backs away from the abyss toward which he’s been swaggering most of his life for lack of a better option.

[TSOTSI] is a timeless parable that captivates, enlightens and encourages us to better understand our fellow man no matter how far he’s fallen. And it does this without lecturing, condescending or pitying. Impossible."

And then Hood made RENDITION and WOLVERINE. Good for his bank account; bad for his art. Come back to us, Gavin.

58. HERO (2002, d. Zhang Yimou, w. Zhang, Li Feng and Wang Bin)

Zhang Yimou's high-minded answer to Ang Lee's CROUCHING TIGER, HIDDEN DRAGON might have some uncomfortable nationalistic undercurrents, but they've never hindered my enjoyment of this gorgeously-shot film. Ching Siu-Tung's exquisite fight choreography and Christopher Doyle's sumptuous cinematography (abetted by Huo Tingxiao and Yi Zhenzhou's production design) combine to make HERO the most stylish and emotionally fulfilling martial arts picture ever produced.

57. BURN AFTER READING (2008, w & d. Joel and Ethan Coen)

From my 2008 review for AICN: "Joel and Ethan Coen's BURN AFTER READING opens with what appears to be a spy satellite's view of a computer-generated Earth. I think. Perhaps it's a model. Whatever it is, it's laughably fake, which means it's a detail the Coens really want you to notice. That this artificiality is accompanied by a bombastic Carter Burwell cue seemingly swiped from John Landis's SPIES LIKE US only serves to heighten the onrushing sense of parody; and as the camera comes crashing down through the fake clouds toward a fake United States and through the fake roof of a fake building in fake Langley, Virginia to reveal real CIA desk jockeys doing really stupid shit, your only response is to put your guard down and let the Coens enjoy their spirited, if inconsequential, NO COUNTRY FOR OLD MEN victory lap. Visually, they've just told you they're up to nothin' but funnin', right?

It's survival of the pettiest, and it's telling that the only person who achieves their objective is the one most hellbent on their own self-interest. But then the Coens' camera retreats from fake Langley, back through the fake clouds and out into the vast expanses of fake space, and we're reminded that people just don't get away with such things in our universe. It sure is swell to live in a world where justice prevails."

56. OLDBOY (2003, d. Chan-wook Park, w. Park, Jo-yun Hwang, Chun-hyeong Lim and Joon-hyung Lim)

The highlight of Butt-Numb-A-Thon V, this bizarro revenge yarn is Chan-wook Park at his most ferociously inspired. Considering Oh Dae-su's prolonged isolation and subsequent rough re-adjustment to regular society, I've always viewed OLDBOY as something of a metaphor for the still-unresolved North Korea-South Korea predicament. But it's so crazily over-plotted that any kind of thematic significance is secondary to the visceral pleasure of watching Oh Dae-su fuck up nearly everything and everyone in his path. First and foremost, this is an audience picture. Nothing wrong with that - not when it's this skillfully done.

55. MUNICH (2005, d. Steven Spielberg, w. Tony Kushner and Eric Roth)

From my Best of 2005 list for Collider: Steven Spielberg’s A Brief History of Revenge. Depicting the 1972 Munich Olympics massacre as the starting point of the modern Palestinian terrorism, Spielberg laments the downward spiral of violence even as he allows that the notion of inaction is patently absurd. Embedded in a breathtakingly assured suspense film that’s as masterful as the best paranoid thrillers of the 1970’s is the unsettling idea that civilization’s capitulation to bloodlust effectively destroyed (or, as some might say, exposed as a lie) the global pretense to morality celebrated after the Allied victory in World War II, ending with a coup de cinema in the picture’s final pan down the island of Manhattan. By utilizing the shadowy methods of the dispossessed as a means of squaring the dispute only begets more atrocities on both sides, and Spielberg pays his audience the compliment of being even-handed, which has been misconstrued by obfuscators on the right as “moral relativism”. There is a discussion to be had on the deploying of factually sketchy events to drive the point home, but dramatic license is hardly synonymous with dishonesty."

54. THE PIANIST (d. Roman Polanski, w. Ronald Harwood)

From my Best of 2002 list for AICN: "An unflinching, unsentimental survivor’s tale of the Holocaust that is ultimately more exhausting than profound. What lingers most in memory is Adrian Brody’s haunting central performance as a man with barely enough strength to endure."

I don't know why I was so dismissive of Roman Polanski's film back in '02, but it's now (correctly) regarded as a late-career triumph for the embattled director. THE PIANIST is a harrowing experience that contrasts jarringly with the saintly-survivor view of SCHINDLER'S LIST; talent, luck and compromise are essential, while decency is a potentially fatal luxury.

53. INTO THE WILD (w. & d. Sean Penn)

From my Best of 2007 list for CHUD: "Sean Penn always seemed on the verge of being a great filmmaker; it was just a matter of wedding his penchant for emotionally unsettled characters to material that wasn't too downbeat. So leave it to Penn to find the inspirational side to trekking off into the Alaskan wilderness and starving to death. This is, of course, a flippant way of saying that Penn personalized Jon Krakauer's fascinating tome about Christopher McCandless's ill-fated quest for a transformative rite of passage. Whereas Krakauer emphasized the cautionary (while trying to defend McCandless's folly), Penn celebrates the brave, kinda-crazy, off-the-grid romance McCandless indulged as a means of rejecting the prescribed path to professionalism set down by his no-nonsense father. It was a selfish journey to be sure, but Penn portrays it as a sacrifice for all those who would never stray from the expected and venture off into the unknown."

52. MASTER AND COMMANDER: THE FAR SIDE OF THE WORLD (2003, d. Peter Weir, w. Weir and John Collee)

From my 2004 DVD Journal review: "It's impossible to imagine [Patrick O'Brian's] books being brought to life by anyone else but Weir, whose ongoing fascination with outsiders entering strange cultures is an ideal fit for the project. Unlike his previous films, however, the characters are all completely at home in their world; it's the audience who's the outsider. When one understands this, that opening, dimly lit tour of the [H.M.S. Surprise], scored to little more than the ambient sound of a working ship at sea, makes perfect sense. It's the moment of enchantment through which Weir works his customary magic, and it lingers undisturbed for a wonderful couple of hours until the closing credits finally breaks the spell. It's as good, as stirring, and as pleasurable as time spent under a reading light with O'Brian's prose."

Tom Rothman, the much-maligned Fox chairman, deserves an enormous amount of credit for getting this (financially unsuccessful) film made. So thank you, Tom, for this immersive, one-of-a-kind cinematic experience. There, I said it.

51. MULHOLLAND DR. (w. & d. David Lynch)

From my 2001 review for AICN: Technically, the film is a marvel. Peter Demming’s cinematography has an absurdly soft glow in daylight, but his most notable achievement is the way he renders darkness as an inescapably malevolent character. No one been this at home in the shadows since Gordon Willis. Meanwhile, Lynch lends this darkness a kind of voice through his sound design; a low, ominous rumble accompanies even the quietest moments, and seems ever on the verge of an abrupt crescendo to a roar. Consider yourself forewarned that Lynch is more than happy to kick the volume up to some frighteningly high-decibel levels (it’s his best use of sound since his perennially underrated TWIN PEAKS: FIRE WALK WITH ME).

Yes, MULHOLLAND DRIVE is not for all tastes; it’ll be anathema for hard-core narrative junkies, and will send the faint-of-heart scrambling for the exits within the first ten minutes. For everyone else, it’s classic Lynch – perversely funny and unspeakably terrifying in near equal measures. To be precise, a masterpiece."

Halfway through. Apologies for relying so heavily on my old reviews for this batch, but it's been a very busy week. I'll be hard at work this weekend writing up as many fresh capsules as possible for the final fifty - which will be posted by Wednesday morning at the latest.

Faithfully submitted,

Mr. Beaks

67. WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE (2009, d. Spike Jonze, w. Jonze and Dave Eggers)