Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Marking Nine Years at AICN....

In 2000, around Thanksgiving, I signed onto to AICN to add anime coverage to its then running Asian media column. Soon there after, as that feature faded away, AICN Anime was spun into its own column. For a couple of years before and for a while concurrent to, covering anime on AICN, I posted running topical updates on the website for the University of Massachusetts Japanese Animation and Manga Society. Initially there was not enough news out there for this to be daily, but I was soon chronicling the start of the anime/manga boom, updating several times a day. Back circa 1998,1999 this was novel, even if it was happening on a university club website rather than a dedicated domain. I'm not sure if I'm going on 11 years of continuous, online coverage of anime and manga or going on 12 years. It took me forever and a day to get the proper access to the UMJAMS site and forget when I actually started. Regardless, I think that I might not be the person who has been continuously covering the topic online the longest, but I am sure that I'm pretty high on the list. I've worked with some fantastic people in the industry, and to you, I say "my deep thanks!" And, I've worked with some challenging people within AICN, and to you, I'd say "regularly reading and responding to e-mail wouldn't kill y'ah!" If it doesn't sound like I'm hugely celebratory about this anniversary, it's because bad luck seems to strike at this point in my calendar. A couple of years ago, my apartment was flooded. This year, a critical laptop bit the dust. So, onward I go, with, as Onion AV Club once titled their book, the tenacity of the cockroach.

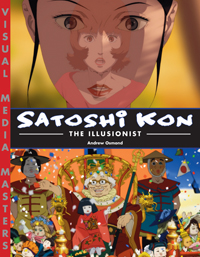

Resource Spotlight: Satoshi Kon: the Illusionist By Andrew Osmond Released by Stone Bridge Press

Speaking of people who have been at it since the late 90's, it's been a couple of years since anime has had a full lengthed Satoshi Kon helmed head trip to marvel at, but he has been heard from again There's been Perfect Blue - 1998 Millennium Actress - 2001 Tokyo Godfathers - 2003 Paranoia Agent - 2004 Paprika - 2006 Then, between then and now, just his one minute Good Morning short for the Anime*Kuri 15 compendium. He had mentioned a project called Dream Machine, telling Anime News Network "The title will be Yume Miru Kikai. In English, it will be The Dream Machine. On the surface, it's going to be a fantasy-adventure targeted at younger audiences. However, it will also be a film that people who have seen our films up to this point will be able to enjoy. So it will be an adventure that even older audiences can appreciate. There will be no human characters in the film; only robots. It'll be like a "robot movie" for robots." Finally, after what could be thought of as an extended quiet period for Kon or typical radio silence for an anime movie production, as noted by Twitch and Catsuka, preview images of Dream Machine have made into the project's official site.In the last decade, movies and video games have made deep incursions into territory that was once the domain of anime and animation in general. There were images that were tremendously difficult to realize in live action and impossible in games, but available to animation. CG and improved game hardware have flipped the script. As a consequence, whole genres of anime have lost their importance. Who wants to sit back and watch elves and dragons fantasy anime, when games often offer a comparable visual experience, while allowing a player to participate. Yet, an area in which anime/animation can still assert an advantage is narratives in which the fantastic is blurred with the objective. Leveraging animation's ability for a director to erase boundaries and exercise nuanced control of the entire image, Kon is the master at this. There's the world as it theoretically is. Then, there is the world as it is reflected in media. Then, the world as it is interpreted by the human mind... subdivisible into conscious and subconscious, rational and irrational. In Kon's anime, these distinctions all collapse in on each other. Often starting with the foundation of a live action associated genre, whether it is Hitchcockian thriller (Perfect Blue), a Christmas story (Tokyo Godfathers) or life in retrospect drama (Millennium Actress), Kon convolutes it with the mind's paradoxes, contradictions and chambers of mirrors. His subjects project their interpretations out onto the world, at times seeing themselves as fantastic beings, dancing through the air or skipping through a city's neon signage. And yet, those interpretations are shaped by pressure from those around as well as a saturation of media influence. Rather than mechanistic stories, Kon's are shaped into knotted feedback loops. Only a handful of anime directors have received English language books. Hayao Miyazaki has been the subject of several. Brian Ruh's Stray Dog of Anime: The Films of Mamoru Oshii is certainly recommendable. Freelance journalist/ film and animation specialist Andrew Osmond's second book is Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist. His first, BFI Film Classics entry Hayao Miyazaki's Spirited Away impressed greatly. In numerous ways, the illusionist fills a gap in the English language library of books on anime. Satoshi Kon is deserving of his own book, and is deserving of a writer as good as Osmond. Neither "Satoshi Kon," the body of works, nor "Satoshi Kon" the person is an easy subject for this sort of examination. His works might not be as obtusely avant-garde as something like Mamoru Oshii's Angel Egg, but they do call out to be interpreted. Beyond that, Kon himself apparently enjoys the role of oracle. Ask a question and he'll provide an answer. Supposedly, during an American appearance, he gave an account of what Paranoia Agent was really about, then undermined the explanation he just revealed. While he's not a Lars von Trier, whose every word needs to be second and third guessed , not taking Kon at face value is also advisable. Osmond not only demonstrates an ability to keep pace with Kon, but proves to be Illusionist's chief asset. The background information on Kon's early years and early career had not previously been easily accessible in an English language narrative. That, in and of itself makes the Illusionist a great asset in advancing the discourse of anime. Osmond interviewed Kon and 1999 and 2007, but beyond that opening personal history, the value of The Illusionist is less data , facts, or original comments from Kon than it is Osmond collating, interpreting and scrutinizing what is known about Kon and his works. Anime has few who write about film as well as Osmond, or simply write as well as him. He offers a clarity in explaining how ideas are expressed through the medium that is not often found in English language writing on anime. A couple of snapshots of Osmond's work... On Kon's use of violence in Perfect Blue Murano's murder especially feels like a nauseous dream, scrambling male and female, killer and victim together. Mima herself holds the phallic blade, but the murder montage includes images from a photo-shoot earlier in the film, where Murano wields a long-lens camera towards the splayed nude girl, echoing Michael Powell's live action Peeping Tom. Even at the end we're not sure if Murano was killed by a man or a women, though there's maybe a clue when see we who wields a chisel at the climax. It's even logically possible (just) that Mima was the killer, as shown on screen. On Paranoia Agent, specifically a crucial confrontation with its phantom child assailant Shonen Bat (the Geneon release used localization "'lil Slugger was not love in many quarters, and Osmond uses the original, Shonen Bat) It's a reminder to the Pulp Fiction and Sin City generation that one can draw attention to artificial devices without irony, as Kon had already done in Millennium Actress. For anime fans, the episode echoes the infamous TV ending to Neon Genesis Evangelion where the action gave way to antirealist monologues in the last episodes. But, Paranoia Agent's approach is both more accessible and more refined, without Evangelion's therapy-speak. I couldn't find fault with Osmond's interpretations, but that doesn't mean that nobody will. In particular, I wonder what someone with a more formed, feministic interpretation of Kon's works would think of Osmond's assessment of ones like Perfect Blue and Paprika. Osmond quick judgements of other anime might provoke reaction. While I don't think that much of an argument can be mounted against the assertion that Vexille is a "lunkheaded" action movie, fans of Makoto Shinkai might not be enamored with the assessment of his work as "drippy." (Speaking of judgements, we get Kon describing an Oshii work as "a story that went nowhere and was nothing but exposition" and criticizing most anime as "extremely samey") Almost any anime fan is going to nitpick almost any work. Comparing Paprika's Goku outfit to Monkey stands out as a British point of reference, where the broadcast of Nippon Television's 1978 live action TV series popularized the Saiyuki character under that name. I also question whether Osmond has the time line for Perfect Blue's international release exactly right. "Perfect Blue opened in America a few weeks before the far more lucrative Pokemon: The First Movie." I think that the VHS of Perfect Blue and the theatrical run of the Pokemon movie both hit in November 1999. As a matter of personal taste, I'm not a huge fan of attempting to shape jokes in picture captions. As such, the likes of "Please to meet you, hope you guess my name... Shonen Bat," and for Paprika's butterfly pinning "Getting the point: Paprika heads into psycho-thriller territory. (But sexy psycho-thriller territory)" slightly irked me. Osmond's writing is far from sterile or over reverent, and I considered that to be a great asset. However, I'm not one for attempting to turn the space under images into a venue for jokes, especially if they aren't in line with the larger tone of a work. After a background chapter, discussing Kon's influences, development as an artist and early works, Satoshi Kon: the Illusionist discusses each of the Kon directed anime works: Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, Tokyo Godfathers, Paranoia Agent and Paprika. The chapters are organized as follows. "In Brief" - a largely plot based capsule description of the subject's concept, with maybe a highlight noted, such as Kon's appearance in Paprika. "Origins" - a look at production backstory, staff notes and inspiration. It's partially about how Kon went about developing and implementing the ideas in question. However, this is also the point at which Osmond draws out the tendrils extendable from the work in question. Given Kon's unusually extensive involvement in his anime, this is an end-to-end look at anime production, from concept through animation. This section also looks at the writers, animators and other contributors involved. English language anime discussion has a tendency towards narrow bandwidth when it comes to creative credits, but Osmond notes the impact of the illustration of Shinji Otsuka (who drew scenes such as transvestite Hana's hospital rant in Tokyo Godfathers), the input of cowriters like Sadayuki Murai (Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, but also Cowboy Bebop, Boogiepop Phantom, 2003 Astro Boy), and of course, the unforgettable collaboration with composer Susumu Hirasawa (Millennium Actress, Paranoia Agent, Paprika, also Berserk) Even before diving into explicit analysis of Kon's work, his alloying of media and reality is unavoidable. For example, Tokyo Godfathers tips its hat to Peter B. Kynes's Three Godfathers and at the same time, focuses on the often pop-media ignored reality of homelessness. The movie evokes youth violence both from and against its protagonists in a manner that tapped into Japan's zeitgeist and news headlines. Yet, some of what could be grounded in the concrete is based in the perception of Kon and the rest of the movie's creators. Concerning the movie's transvestite, gay character Hana, Osmond quotes Kon in saying "I had a lot of concern that some people, such as gay people, might get angry with me, or people might lay claims on me because of how I depicted the homeless. I really worried about it. There was no model for Hana; I did not create him by researching the gay community. The story needed someone like him, and in creating him, the story was enhanced. That's the only explanation I can give." Perfect Blue and Paprika, Kon's first and most recently released movies were based on novels, and these sections survey the adaptation process applied to the original prose. But, beyond that, the media that has influenced Kon and the media that did not proves to be an interesting subject forThe Illusionist's inspection. Though Perfect Blue is often compared to the works of Dario Argento, Kon hadn't seen any of the giallo director's works before interviewers started raising the subject. However, Kon is a movie fan. George Roy Hill's Slaughterhouse-Five is high on his list, as are the works of Terry Gilliam. "Kon especially rates three of Gilliam's early fantasies, Time Bandits, Brazil, and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen... he explained 'they're excellent films which mix dream and reality. The brilliant thing about Gilliam's work is his bitter criticism of inert and stagnant societies such as our own, as well as his childlike imagination and creativity." "Opening Scenes" - how kon initially presents his idea, crafts a first impression and in doing so, sets up his narrative sleight of hand. The noun "fake" comes up a number of times. After Perfect Blue, Kon's viewer likely new that they were being set up for a trick. However, unlike a M. Night Shyamalan film, anticipating the twist doesn't spoil the movie. In a set of works whose convolutions fascinate, it's interesting to isolate each work's teasing preamble and see how they compare. "Synopsis" - what occurs during the course of the subject work. These are nicely evocative box scores of the movies and TV series; for Paranoia Agent, it is an episode by episode account of the 13 part work. Osmond has a good hand for applying the twists of Kon's narrative to even, objective catalogues of the events of the stories in question. "Key Scene" - transcription of dialog with Osmond's reverse engineering of director's notes from a pivotal point in the subject work. "Analysis" - the championship rounds of a Satoshi Kon engagement. Osmond proves to be up to the task. I don't think that Paprika and company are any more available for a definitive analysis than Apocalypse Now or Cache. Nor to I think that Osmond's take is liable to steamrolls yours. Yet, it would be difficult to avoid nodding in agreement with the map to interpreting Kon that Osmond lays out over the course of the Illusionist. Entries are accompanied by running sidebars of "Points To Note" - collections of look for's, be aware of's and so on, feature items of interest concerning, voice actors, on screen appearances, connections and references. For example, what was edited in American television airing of Paranoia Agent, the movie references in Paprika, closest person to the real model for Millennium Actress' title character. There's plenty of lamenting of what sometimes appears to be the end time for anime and manga, or at least the finale for these media in North America. I'd to think I wouldn't have joined in on the kvetching if I thought the pessimism was entirely unfounded. Neither anime nor manga is facing existential challenges in Japan, but both have defining concerns to work through. At least in regards to the US anime industry, the question is out there as to whether there's support for much competition, or any print periodicals. While I'm concerned about the future, I'd single out 2009 as a great year in what I'd argue has been a great decade for anime and manga. And, not to get too Oprah, but Satoshi Kon: the Illusionist is one of the outstanding things about 2009, reflecting one of the outstanding things about the decade. 2009 has had some interesting works to offer readers. Artfully adult gekiga manga, such as a Drifting Life and Red Snow for one. It's also been the best year for mature comedy since the Pulp anthology ended, with releases like Sayonara Zetsubou Sensei, Little Fluffy Gigolo Pelu, Detroit Metal City, and the Sigiki lineup. And, 2009 might be the best year for English language topical books, ever (2007 is a contender). I'm probably forgetting some, but the ones I can think of include In conversations I've urge people that "if they buy one anime or manga related book this year, buy X," with the recommended title changing a half dozen times. I'm not sure that my fickle favoritism will settle with Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist as my ultimate chose, but I like the idea of it being the final favorite anime book of the final year of the 00's.

- 500 Essential Anime Movies: The Ultimate Guide (haven't seen)

- Abram's Art of Osamu Tezuka and Manga Kamishibai

- God Of Comics: Osamu Tezuka And The Creation Of Post World War II Manga (an academic look at the works of Astro Boy creator Osamu Tezuka)

- Hayao Miyazaki's Starting Point: 1979-1996 (essays by Hayao Miyazaki)

- Mechademia 4 (haven't read yet)

- Otaku Encyclopedia (covered here)

- Otaku: Database Animals (a translation of a Japanese work, slightly out of date, but a keen view of the mindset not only driving anime fans, but, increasing its creators)

- Rough Guides to Anime and Manga (the manga one was more North American focused than what I was interested in, but I was very impressed by the anime guide's insightful overview)

- Schoolgirl Milky Crisis: Adventures in the Anime and Manga Trade (covered here)

- The Anime Machine: A Media Theory of Animation (haven't seen, plan to order)

- ga-netchu! The Manga-Anime Syndrome (essays from exhibition catalog of "Anime! High Art - Pop Culture" at

- Deutsches Filmmuseum, worth importing if you're interested)

Among the gripes articulated by us death of anime bemoaners is that anime for older audiences has been narrowing its focus in on moe, infantilism and questionable sentiments towards young, 2D girls. Yet, this has been a stupendous decade for anime for adults. While many of the trends started in the late 90's, they came to fruition in this one. Late night anime (TV Tokyo's airing of Serial Experiments Lain and Boogiepop Phantom) and satellite (Animax's Berserk, WOWOW's Big O - Cowboy Bebop might count for both) have yield numerous favorites. Programming blocks like Fuji TV's noitaminA (Honey and Clover, Paradise Kiss, Ayakashi - Classic Horror and Jyu Oh Sei) have sought to expand the audience for anime. Studio4C came into their own (see the Genius Party feature) with features like Princess Arete, Mind Game and Tekkon Kinkreet. With Ghost in the Shell taking them out of the 90's Production I.G continued producing Mamoru Oshii directed or conceived works, such as Jin-Roh: The Wolf Brigade, Blood: The Last Vampire, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence, Skycrawlers, and Tachigui: The Amazing Lives of the Fast Food Grifters, as well as boldly innovative works like FLCL, Dead Leaves, Kai Doh Maru, and Otogi Zoshi. And Madhouse continue to be the home of unique works, including a host of TV series like Black Lagoon Dennou Coil, Monster, Oh! Edo Rocket, Paradise Kiss, and Texhnolyze that could hold the interest of an adult audience, as well as movies like Rintaro's adaptation of Tezuka's Metropolis, Ghibli animator Kitaro Kosaka's cycling anime Nasu: Summer in Andalusia and Mamoru Hosoda's The Girl Who Leapt Through Time. Then, there's the work of Satoshi Kon. He previously wrote manga, had a major role in the Magnetic Rose stories of the Memories anime triptych, and his Hitchcockian psycho thriller Perfect Blue debuted in 1998, but with Millennium Actress (2001), Tokyo Godfathers (2003), Paranoia Agent (2004) and Paprika (2006), the 00's have been Kon's decade. Kon was not the darling of anime fans from day one. Perfect Blue was a divisive subject when it first started making the rounds. Its invocation of sexual violence certainly provoked some ambivalence, but as I remember the movie, it was its internet illiterate lead that cause much of the derision that the movie came in for. Nor has Satoshi Kon became a universal lauded figure. In Cartoon Brew's report from Annecy 2004 TOKYO GODFATHER: Like Satoshi Kon’s earlier film MILLENNIUM ACTRESS, this opening night film of the festival also whisked me away into a deep slumber. But that’s not the surprise. Following the film, I ran into animation legend Ray Harryhausen at the opening night party, and we chatted for a bit. He asked me what I had thought of TOKYO GODFATHERS and I admitted that I fell asleep during the film. Ray then gave his review of the film, and in the process showed me why he’s a legend: because he has great taste. Ray said there was absolutely no reason to produce GODFATHERS in animation because it didn't take advantage of the medium. He also pondered why the filmmakers had designed all the characters to be so unappealing and ugly. I didn't think there was any way I could have more respect for Ray Harryhausen than I already did, but he showed me a way. Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist certainly grapples with that question - particularly in the context of Tokyo Godfathers, but also in the introduction and throughout the chronicle of Kon's career. Those have become minority opinions. In the venerable anime periodical Protoculture Addict's Top Directors Who Aren't Hayao Miyazaki cover feature, Satoshi Kon occupied the list's zenith. It's not just the anime writers who have become Kon admirers. Anime random has demonstrated a thin bandwidth for creator credits. For example, Koji Morimoto is a prominent figure in anime. He cofounded Studtio 4c. He was involved with numerous memorable works, including the Beyond segment of AniMatrix and the Nike Chamber of Fear ad. Yet, he's the type of creator anime fans simply don't know. Sometime between Perfect Blue and Millennium Actress, Satoshi Kon became a name that anime watchers could not ignore. Japanese gaming magazine powerhouse Famitsu ran a survey of American otaku The results were What's been missing in this respect for Kon has been a creator narrative. Prominent in Manga Kamishibai's chapter on the modern forms of anime and manga was the statement "Though he was too young to be influenced by kamishibai, Satoshi Kon started in the 1980s as a manga-ka and went on to create the anime series Paranoia Agent and the acclaimed anime Millennium Actress - a kaleidoscopic recap of Japanese film history, including the years in frozen Manchuria. " While nothing in there is factually incorrect, it implies a transition from manga to televised anime to movies and in context, it suggests a normality to the path. As outlined in the Illusionist, one sees how Kon became a force in anime for mature audiences/. Earlier, I said that this has been an outstanding decade for anime for adults. Still, an artist like Satoshi Kon is a rare quantity, and that there was A Satoshi Kon working in the 00's is a notable distinction. Before smart phones and Nintendo DS took over, manga was read by all audiences. Anthologies like Big Comic could be read by an adult without embarrassment. Anime's a different story. For the most part, it's made for children and geeks. Accordingly, the few anime movies that do get released are by a large majority, the annual tie-ins to popular boys' (shonen) franchises like Naruto or One Piece. There have been and are still are shonen shojo anime, and even shojo anime movie franchises (Precure), but even that gender interests group are underrepresented in anime. Part of the value of Osmond's book is that it explains that while Kon grew up with an appreciation for geek classics like Battleship Yamato and Gundam, and while his opinions towards anime fans and their dedicated otaku subset are nuanced, he has an antipathy towards shonen contests of power like the above mentioned Naruto and One Piece. The Illusionist does not explicitly say as much, but a creator like Kon, with interests in cinema and the full dimensions of the human mind is not apt to be drawn to reducing thought and relationships to types, as often happens in bishojo (cute girl) anime. As Osmond quotes Kon from a 1999 interview "Animation based on popular comic books and giant robots and big-eyed girls with shamefully skimpy costumes will continue to fill the screen. I think that's okay. These productions fill demands; the audiences for them support the Japanese animation industry. Thanks to them, there is room for a non-mainstream creator like me. Of course, I hope many unusual pieces will also appear." The Illusionist notes that when Perfect Blue first hit North America in 1999, anime still had the "not for kids!" branding of sex, violence, and sexual violence established by the likes of Akira, Ninja Scroll, Urotsukidoji and MD Geist. By that warped perspective, Kon's movie was a smart, arguably more empathetic, take on anime's customary subject matter. A decade later, North American audiences possessing at least a causal familiarity with anime can recognize that Akira is a singular work and that, for better or worse, titles like Ninja Scroll and MD Geist represent a minority of anime productions. Perfect Blue wasn't simply a notable marker on anime's home turf. Kon's revisiting of that exceptional approach in different genres and topics across three movies and a TV series over the 00's has been a boon for fans of animation that speak to an adult audience. In fleshing out how and why Kon engaged that material, Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist becomes a book that anyone with an interest in mature anime ought to read.

- Hayao Miyazaki - Oscar winning direct or Spirited Away, the saint of anime

- Shinichiro Watanabe - director of one of the most western appealing anime, Cowboy Bebop

- Kyoto Animation - animators of several comedies finely tuned towards appealing to otaku, most prominent being the Melancholy of Haruhi Suzumiya

- Gainax - home of Otaku no Video, the studio formed by dedicated geek, who would go on to make the otaku redefining Neon Genesis Evangelion

- Hideaki Anno - creator direct of Evangelion

- Satoshi Kon

- bones - animators of the Cowboy Bebop Movie, Fullmetal Alchemist

- Sunrise - home of Gundam, Code Geass, and many of the other long mecha anime

- Studio Ghibli - home studio of Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata (Grave of the Fireflies, Pom Poko)

- Akiyuki Shinbo - probably the list most obscure. He has a number of works that are commercially available in English, including The SoulTaker, Le Portrait de Petit Cossette, and Pani Poni Dash, but he's really gathered a following from his extravagantly clever works that haven't been licensed, including Sayonara Zetsubo Sensei, Maria Holic and Bakemonogatari

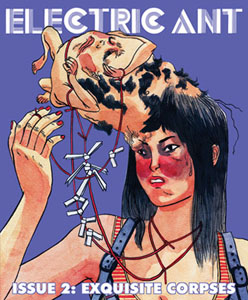

Zine Spotlight: Electric Ant 2: Exquisite Corpses See the official site here

ELECTRIC ANT #2 PREVIEW from ryan sands on Vimeo.

As stated when covering the first issue of the Electric Ant zine, if you're not following it's parent, Same Hat! blog, be sure to add it your book marks for RSS feed reader ASAP. The banner phrase seems haven scrubbed away in a recent design, but, Same Hat! still is "manga commentary, featuring horror, gag & erotic-grotesque nonsense." Last year, one of the anime conventions that I attended offered a panel on "ero guro." I was disappointed to find it was largely an internet harvested slide show of shocking illustrations, many of which were intended to be titillating. What upset me about the intentionally upsetting collection of images presented at the panel was the dearth of context offered. As a concept, it's deeper and more interesting than just a label for images of naked girls in the midst of grievous bodily harm. And, it's a subject that genre fans could benefit from a familiarity with. "Ero guro nansensu" (erotic, grotesque nonsense) was an artistic movement of Japan's Taisho era, a liberal time, also known as the "Taisho democracy," between the rapid modernization of the Meiji period and the war time that would open the Showa period. I don't think Germany's Weimar Republic is an entirely misrepresentative comparison. The movement looked to precursors in ukiyo-e prints like the infamous sea creature erotic encounter, Dream of the Fisherman's Wife and found itself tied into true crime sensationalism, such as the 1936's Sada Abe case, in which a woman strangled and castrated her lover, then carried around the severed organ in a bag. It would inform the abnormality infused work of Edogawa Rampo, a titan in Japanese crime and sci-fi fiction. Many forms of media still look back to ero guro, but, relevant to this column, its imprint can be seen in the work of manga artists such as Suehiro Maruo and Shintaro Kago. Bringing the conversation full circle, Ryan Sands and Hayden, the folks behind Same Hat! (and the English release of Tokyo Zombie) will be localizing Last Gasp's release of Suehiro Maruo's manga adaptation of Edogawa Rampo's The Strange Tale of Panorama Island. From Same Hat Panorama is an adaptation of a novella by Japanese detective fiction godfather, Edogawa Rampo. The story takes place at the end of the Taisho era, and follows an unsuccessful science fiction author with an uncanny resemblance to a former classmate/son of a rich industrialist family. When the industrialist's son dies, the author fakes his own death, digs up and hides the other man's body, then washes himself up starving on a beach in a town where the dead man's family lives. After some more intrigue and scheming, he proceeds to take redirect all of their money to build a mysterious pleasure palace island, and live like a sensual weirdo king. Crazy and amazing stuff! The name "Electric Ant" was chosen to mark the Sands edited/Hayden designed zine as a tribute to Philip K. Dick and Suehiro Maruo. It's not entirely ero guro nansensu, but does flow seamlessly into and out of the rapids in which pop culture takes a severe battering on that particular set of jagged rocks. Exquisite Corpses commences in territory that is not ero guro, but addresses that topic an attitude and approach consistent with the later savagery. The issue's chief feature concerns the Takarazuka Revue, a theatre troupe in which all parts are played by female performers. Takarazuka Revue has had a significant role in the history of anime and manga. Takarazuka is the home town of the great innovator of both of those media, Osamu Tezuka. As a child, Tezuka's mother often brought him to performances of the theatre group. He would go on to transform manga by rejecting its front and center theatrical view of the action in favor of a more fluid, cinematic one. And yet, Tezuka also paid tribute to theatre and Takarazuka specifically over the course of his work. In the essential example, Tezuka looked to the pageantry and costumes of the theatre when creating Princess Knight, a prototype for modern shojo, in which a princess with male and female hearts assumes the identify of a prince to protect her kingdom's throne and of the masked Phantom Knight to fight injustice. A similar aesthetic was tapped into in Riyoko Ikeda's Rose of Versailles, a critical part of the Year 24 Flower Group's movement towards shojo manga written by women. In the case of Rose of Versailles, the Takarazuka Revue influence came full circle, with Ikeda's story of a noble girl raised as boy to become a palace guard in the court of Marie Antoinette adapted into a musical with which Takarazuka Revue is often associated. In the 90's the Princess Knight/Rose of Versailles lineage was continued in Revolutionary Girl Utena. And, the two institutions still reference each other, in instances like the Takarazuka parody in Ouran High school Host Club. Sands writes about Takarazuka Revue, then interviews Zehra Fazal, an actress and playwright (her current work is one woman comedy/musical Headscarf and the Angry Bitch) who interned at Takarazuka. The history and significance of Takarazuka Revue are explained in the feature. His introduction concerns the institution rather than the anime/manga connection outlined above. If you don't know about Takarazuka or have vague familiarity, the piece will build an understanding of Takarazuka's style of performance. Yet, the intension here seems less didactic or analytical and more about impressions and personal experience. Though Sands was not embedded in the institution the way that Fazal was, he still offers a record of touching the source. Some people are pre-disposed toward being fascinated with Takarazuka, and maybe Electric Ant will be some predisposed person's first exposure, but even if you're not inclined towards a topical interest, Electric Ant is still offering a memorable account of an experience with an interesting institution From the editors's note, concerning the theme "Exquisite Corpses" - "In a word, Collaborations. In another word, Bodies... On the bodies tip, we tackled the gender bending of Takarazuka Revue, transsexual bars in Shinjuku, dominatrix training, German gay softcore films, and more." Consistent with the Takarazuka pieces, the rest of Electric Ant's text pieces are not reconfigured into an overly ordered lattice and not at a sterile distance. From the attention seizing Hellen Jo cover to the work throughout, Electric Ant features of a searing collection of exceptional artists who, if you don't know, you should. Graphical work includes the jam comic "Planet X Rises," "These Bloody Moments and the feature comic Empire Anthony Ha and Anthony Wu's "Asian Citizen Kane... in space!" AICN readers will find something to delight in the jam comic, which experimented with what talents artists could do with the rules 1) a man loses a tooth, only to find an ominous message hidden inside 2 A doomsday cult believes the world will end unless a seal named Tama is rescued 3 At some point, our protagonist must go on the run! Oral violence and men in the guts of seals ensue. "These Bloody Moments" is really the sort of exercise of ero guro nansensu mindset that a reader of this column could delight in. "Two dozen graphic depictions of violence from film, tv, books, and games." Consequently, the most cleverly beautiful, I guess you could call it fan art, of Final Fantasy VII (by Angie Wang) I've seen finds a place between a furious bit of Titus Andronicus by Mickey Zacchilli and a disconcertingly too real splash of An American Werewolf in London by Aeron Alfrey... not to mention tributes to Salo, Mars Attacks!, Robocop and more... worth the price of admission for a genre geek in and of itself.

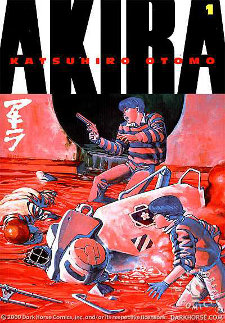

Manga Spotlight: Akira Volume 1 by Katsuhiro Otomo Released by Kodansha Comics

On April 28, 1952, Japan regained sovereignty following its post World War II occupation. The 50's began a decade in which Japan began supplanting destruction and scarcity with industrial strength. In 1956, manga artist Mitsuteru Yokoyama channeled this evolution in Tetsujin 28-go (localized Gigantor), the story of orphan Shotaro Kaneda, whose father left him the radio controlled steel girdered titan Tetsujin 28. Where Tetsujin was once intended to be used as a weapon of war, under Shotaro's control, he became a hero a new age of science and machinery. By 1964, Japan had emerged as a technologic and economic power, a transformation celebrated by the 1964 Tokyo Olympic Games. Beyond this established national pride and success, the 60's were also a decade that saw the rise of student protest movements, the likes of which famously informed the works of Mamoru Oshii, such as Patlabor, Jin-Roh and Blood: The Last Vampire: Knight of the Beast. Katsuhiro Otomo, born in 1954, chose to offer a bleak reflection of those changes in his seminal Akira. His Tokyo was bombed out in the opening instants of World War III. Rebuilt in the following four decades, by 2030 this Neo-Tokyo is about to resume its place among the global capitals with a new Olympic Games. Yet, it is marred by a blast crater that's become an irremovable part of the urban anatomy. As Susan Napier famously stated in Anime: From Akira to Howl's Moving Castle "psychoanalytically, the crater may be read in terms of the both the vagina and anus." And, despite the neon and skyscrapers, the city is not a locale that has been fixed by an urban revival, as seen in it's opening pages in which a gang of youth bikers from the dive bars, detention centers and orphanages screech down derelict high ways, past abandoned barricades, towards that crater. Otomo's Shotaro Kaneda is among that group, an astute, yet reckless 15 year old, able to snatch a gun and point it at the needed hostage without hesitation, able to ferret out and hide critical information, and also prone to hitting on any girl in sight and diving out of second story windows. And, Otomo's Tetsujin is among the bikers, Tetsuo Shima - who serves as the gang's tentative slowpoke, but who is fated to becomes a raging Frankenstein's Monster. The third element of Akira's Tetsujin 28 trinity is Colonel Shikishima. Named for Professor Shikishima, former assistant to Shotaro's father and ally to the boy, Akira's Shikishima is a barking military officer whose project is about to blow up in the face of that gang. Trying to assert himself in the pack, Tetsuo pulls his motorcycle into the front as the group barrels down the unused, blackened highways. Catching the form in his headlights, Tetsuo pulls off to avoid hitting a shriveled boy like figure with the number 26 branded into its hand. Before the bike can hit the child, the machine explodes. As Tetsuo convulses on the pavement, a pair of uniformed men pull up, mean mug Kaneda and co, radio base, and remove Tetsuo from the custody of the dumbfounded bikers. What happens next is not easily distilled. Tetsuo is in and out of government custody, rapidly developing psychic powers. Kaneda is in and out of his ramshackle vocational school, searching for Tetsuo between biker gang rumbles, hitting his home bar and chasing an anti-government terrorist girl into danger. I assume that the Akira anime isn't as widely seen now as it was in the VHS days, where it was king of the Blockbuster shelf. Yet, the 1988 feature, which not only raised, but largely established the profile of anime for adult audiences, is still probably useful as a point of reference for many North American genre fans. That anime was adapted by Otomo during the run of his Akira manga. Though it was Otomo translating his own work, the latter part of the Akira manga is substantially different from the ending of the movie - something also found in the comparison between Hayao Miyazaki's Nausicaa anime and manga. While there aren't the fundamental differences to be found in later parts of the manga, the first book is certainly reconfigured. For example, the battle against the gang of drugged out, face painted Clowns take place later and from different reasons than in the movie. Like the animated movie, the manga is dizzying. No human force governs the action with anything close to definitive authority. Everyone is going on about how time is of the essence. Kaneda moves through this world with sly cockiness, but he's getting bloodied by authorities and locked into rooms like the kid he is. The Colonel might be cooking the budgets and leading the nation by its nose, but he's still cut off at the knees by the likes of Kaneda, not to mention scrambling to keep up with the dynamic situation. The terrorists know more than they should, but are still often mistaken and reduced to confused tools. Politicians thinking that they are working all sides are still fumbling through comically encumbered committee meetings. Akira's illustration keeps pace with its frantic narrative. With an eye towards the thin lined details of European artists like Moebius, the rush through the painstakingly realized environs of Neo-Tokyo inhabits the brink of overwhelming. Nothing is spared as Otomo commits to capturing the trash, graffiti and broken down buildings as the seedy parts of town elbow in on the glitzier and more industrial districts. It's the 80's urban technopocalypse writ large. Though many works have been inspired by the approach, few, if any, have equaled it. Something like Eden: It's an Endless World might update the ingredients of Akira, but not with the full impact of its forbearer. Akira barrels down this crowded channel, with the 400 pages of the first volume screaming with motorcycles hurtling down highways and hovering gun platforms blasting through sewers. Otomo both manages and accentuates the action with a directorial eye towards staging. Akira may be manga's king of speedline use, but Otomo bolsters that visible velocity with a keen understanding for lighting and angle that makes the movement look comprehendible and feel genuine. With the on again, off again efforts to turn Akira into a live action movie, fans of the anime and manga are often left asking "why?!" and "how?!" Landscaped between the bomb crater and the Olympic stadium, Akira is definitively Japanese. The manga delves deeper into native concerns as it draws in the subject of imperialism, such that those who have finished the manga may regard the prospects of a Hollywood Akira as a real head-scratcher. I'm indifferent to the notion of an American produced live action Akira; not inclined to look forward to it, or rail against it. Yet, while I'm not convinced that the producers WILL do an effective American Akira, I do think that they CAN do an effective one. During the last round of talk about the movie, it was stated that the story would be transplanted to a version of New York City, rebuilt with Japanese money - presumably to capture the aesthetic of the manga. I'd go a different route. I think a relevant Akira should have foreign involvement distant and looming rather than present. 9/11 and terrorism certainly cast a shadow over the consideration of the proposed setting of a rebuilt New York City, but it might be the Great Recession that has brought about the proper cultural moment for an American Akira. While it is borderline offensive to compare the current state of the US to anything like the post World War II rebuilding that informed Akira, more Americans than any time in decades can identify with Akira's dystopian take on that re-ascendance. On one hand you have a broken system, with the crumbling school system, crumbling infrastructure and rampant disorder. On the other, you have the powers that be in the throes of the urge to move past the crisis, call the problem fixed, and mark the success with something like Akira's Olympic games (or stock market rebound). The story's youth heroes are institutionalized in the vague hope that they'll learn to conform and toe the line. Yet, without much to do, many prospects or a viable opposition with which to rebel, all that remains for them to do is drop some pills and tour the destruction. Find a lead with enough charisma to reflect Kaneda's spark and you have yourself an effecting movie. Think of it like Richard Kelly's Children of Men. Back to the concrete from the what if... This release adds a new chapter in the storied English language publication history of Akira. The manga first hit the US with the 1988-1995 run by Marvel Comics' Epic label, commenced the same year that the anime movie was sweeping the international scene and colorized by the Otomo selected Steve Oliff. The work was serialized across 38 issues, which were collection into 13 paperbacks and six hard covers, and it featured tribute art from the likes of Dave Gibbons and John Romita, as well as a Warren Ellis written tribute story. During the crest of North America's manga boom, Dark Horse picked up the license and from 2000 to 2002 released it with a new translation in a format that more closely adhered to the Japanese original - six black and white (with opening color pages) volumes. Then, Dark Horse's publication went out of print, a sign that suggested a confirmation of the chatter that Akira's Japanese rights holder, Kodansha, would be entering the North American manga publication market. In fact, that rumor has come to pass this fall. Kodansha is one of the major manga publishers/licensors, whose anthologies include notable shojo - Nakayoshi (Sailor Moon, CLAMP's Cardcaptor Sakura and Magic Knight Rayearth, Tezuka's Princess Knight), shonen - Weekly Shonen Magazine (Air Gear, Fairy Tail,Sayonara Zetsubo Sensei, School Rumble, Love Hina ) and seinen Afternoon (Oh My Goddess!, Parasyte, Blame!, Blade of the Immortal). Dark Horse apparently lost Akira and Ghost in the Shell in the transition, but continue to release works like Oh! My Goddess and Blade of the Immortal, and have acquired the rights to Kodansha's CLAMP releases, including Cardcaptor Sakura, Magic Knight Rayearth and Chobit (formerly released in North America by Tokyopop). In turn, TOKYOPOP's relationship with Kodansha appears to have been severed with the fate of works like Initial D, Beck: Mongolian Chop Squad and the various GTO spin-offs in question. Del Rey still releases numerous Kodansha titles, and has also picked up a few formerly released by Tokyopop (Samurai Deeper Kyo). In fact, Del Rey Manga's parent Random House has partnered with Kodansha, and begun handling the distribution and marketing of Kodansha Comics. In their venture into the English language market, Kodansha doesn't seem to be quick to lay down new road. Beyond Akira and new editions of Masamune Shirow's Ghost in the Shell, the only material that they've so far indicated plans to release is the upcoming Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex manga, which include Masayuki Yamamoto's Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex - Tachikoma na Hibi, based on the comedy shorts starring Stand Alone Complex's Tachikoma AI tanks and Yu Kinutani's adaptation of the anime. The Kodansha release of Akira is a minor upgrade of the Dark Horse one. It's another six volume distribution - the next two volumes are planned for January and April 2010. The same localization is used. Paper quality is a bit better, leading to a noticeably thicker book. I gave away my limited Dark Horse hard cover, so I'm not sure how the paper quality compares to that iteration. There's a new introduction by Katsuhiro Otomo, but the original prose is less than a half dozen sentences. The Kodansha Ghost in the Shell lacks the pages of cyborg Motoko Kusanagi's stoned, Sapphic vacation activities that were excised then re-added to Dark Horse's releases of the material. There's no reason to be ambivalent about the Kodansha Akira release. It's just not urgent. If you haven't read Akira, I'd tell you that it's bookshelf manga, a classic deserving of its reputation that warrants a place in any library of manga, regardless of how large or selective the collection may be. If you own the Dark Horse release, Kodansha offers little reason to replace what you have.

Upcoming in Japan

Promos and Previews Trigun: Badlands Rumble - teaser for the anime movie due out in 2010Katanagatari - based on NisiOisin light novel Darker Than Black: Black Contractor OVA. The Black Contractor Durarara Perfect Guide - an intro to the new anime from the makers of Baccano, based on light novels by Baccano's author Mai Mai Miracle Higanjima Korean/Japanese co-produced adaptation of horror manga Anime Singapore's Storm Lion Pte Ltd and Japan's Production I.G, Inc. announced at the Animation Asia Conference a collaboration between the two companies in the creation 3D CG animated feature film Titan Rain. The movie is to be directed by Atsushi Takeuchi (mecha design and key animation Ghost in the Shell and Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence ), based on a story by Tow Ubukata (le Chevalier d'Eon) and Edmund Shern, TITAN RAIN will also feature characters and concepts will be designed by Takashi Okazaki, the world-famous creator of “Afro Samurai.” Bear McCreary (Battlestar Galactica) will be providing the soundtrack. * Sci-fi anime director Tatsuo Sato (Nadesico, Stellvia) is on board to direct Satelight (Aquarion, Noien, Macross F) produced Mini-skirt Space Pirates, based on the light novel by Sasamoto Yuuichi. Speaking of Sato's work, Nadesico will be will released on Blu-ray in Japan on February 24, with the TV series along with the Prince of Darkness movie and The Gekigangar 3 OVA. Stellvia will be released on Blu-ray on March 24th.* PEACH-PIT of Rozen Maiden and Ryukishi 07 of Higurashi will be collaborating on the anime adaptation of horror/mystery PSP game Okami Kakushi The anime is slated to be aired from January 2010 on TBS, BS-TBS and Sun TV The opening song "Tokino Muko, Maboroshino Sora(Over the time, Beyond the sky)"is done by FictiionJunction (Yuki Kajiura and Kajiura ), which will be their second single as a group. The ending song "Tsuki Shirube(Sign of the Moon)" is written and composed by Takumi Ozawa and sung by Yuuka Nanri, known for Mobile Suit Gundam SEED and .hack//Roots. Nanri was once a vocalist of FictionJunction and became solo singer in 2009.* Shonen Jump demon-boy manga Nurarihyon no Mago by Hiroshi Shiibashi will be adapted into anime.* Ohba-Kai's 4 panel comedy about Tono to Issho, concerning generals during the Warring States sengoku period of Japanese history, will be adapted into an anime series In conjunction with the upcoming Fate/stay night Unlimited Blade Works movie, the original TV series adaptation of Type-Moon's story of a battle between legendary heroes summoned to fights as proxies in modern Japan, will be re-released in Japan on two special edition Blu-rays. New animation and music is being produced for the re-edit of the TV series.* The Girl Who Leapt Through Time director Mamoru Hosoda stated at Singapore's Anime Festival Asia that he was offered a chance to direct the upcoming Haruhi Suzumiya movie, but that connection didn't work out.* "slow-life anime," (ennui-style) Peeping life is getting a new set of five shorts* Otaku2 reports that following the end credits of the Macross Frontier The False Diva Movie there was a very short clip of space battle animation and some illustration art of Ranka & Sheryl ending with the title for part two “The Wings of farewell".* Captain Harlock creator Leiji Matsumoto has animated a music video based on Queen's "Bohemian Rhapsody" Manga Natsume Ono (Ristorante Paradiso and House of Five Leaves) has launched new manga Tsuratsurawaraji ~Bizen Kumada-ke Sankin Emaki~ in the Morning2 anthology. As described by ANN, set in the Edo Period, the manga follows the long journeys of the daimyo Kumada's family between the capital and the family's Okayama home in southwestern Japan.* Hisaichi Ishii's four panel Nono-chan has been put on hiatus from its newspaper syndication while Ishii is on medical leave. " Nono-chan" is the latest name for My Neighbors the Yamadas, the family comedy adapted into Isao Takahata's Ghibli movie Live Action The upcoming Japanese DVD release of the third 20th Century Boys movie will feature 11 minutes of new scenes, including a new epilogue showing the fate of some of the manga adaptation's characters Tatsuya Fujiwara will be returning for a second live action film adaptation of gambling manga Kaiji Masaru Nagai will also be back in the title role of a new iteration of TV drama adaptation of manga about a biker who reinvents himself as a business man, Salaryman Kintaro Kyoko Hasegawa will play the lead role in the live action TV drama adaptation of work place manga Angel Bank: Dragon Zakura Gaiden

Upcoming in North America

Adult Swim is now offering a custom DVD service, where users can select up to 110 minutes of content with a cover image and menus for $20 CMXMY DARLING! MISS BANCHO VOL. 1 Written and illustrated by Mayu Fujikata CMX. Souka and her mother are looking for a fresh start, so they move to a new place where no one knows them. Souka embraces the idea of starting over and leaves her private school days behind to enroll in the local tech academy. But the first day of school is nothing like she imagined it would be—she is the only girl around! Unfortunately, not everyone welcomes Souka with open arms, including the school leader. But when she takes him down in front of everyone, Souka becomes the new boss on campus! Advance-solicited; on sale March 10 • 5" x 7.375" • 192 pg, B&W, $9.99 US • TEEN DEKA KYOSHI VOL. 2 Written and illustrated by Tamio Baba Advance-solicited; on sale March 24 • 5" x 7.375" • 162 pg, B&W, $9.99 US • TEEN + KING OF CARDS VOL. 9 Written and illustrated by Makoto Tateno CMX. Final volume! Manami tries to apologize to Ko and explain why Araki, his rival for Manami’s affections, has the ring she lost. Advance-solicited; on sale March 31 • 5" x 7.375" • 200 pg, B&W, $9.99 US • TEEN OH! MY BROTHER VOL. 2 Written and illustrated by Ken Saito Advance-solicited; on sale March 31 • 5" x 7.375" • 192 pg, B&W, $9.99 US • TEEN + THE LIZARD PRINCE VOL. 2 Written and illustrated by Asuka Izumi Advance-solicited; on sale March 3 • 5" x 7.375" • 192 pg, B&W, $9.99 US US • EVERYONE FROM EROICA WITH LOVE VOL. 15 Written and illustrated by Yasuko Aoike Advance-solicited; on sale March 10 • 5" x 7.375" • 184 pg, B&W, $9.99 US • TEEN I HATE YOU MORE THAN ANYONE VOL. 9 Advance-solicited; on sale March 17 • 5" x 7.375" • 192 pg, B&W, $9.99 US • TEEN FUNimation FUNimation Entertainment announced that it has acquired home entertainment, broadcast and digital rights to the 26 episode sci-fi action anime series “Testuwan Birdy Decode” from Aniplex. Based on the manga and four episode OVA series, the anime is directed by Kazuki Akane (“Escaflowne: The Movie” and “Heat Guy J”) and animated by A-1 Pictures Inc. (“Big Windup!” among others). ABOUT Tetsuwan Birdy Decode Birdy is an interstellar space agent sent to Earth to investigate the appearance of aliens under the secret identity of a popular Idol. A frantic late night mission causes her to catch an innocent schoolboy, Tsutomu in her deadly line of fire. Thanks to a special space technology, Birdy knows a way to restore his life by joining their two bodies into one. Now Tsutomu and Birdy must share the same body, mind and adventures while the his body slowly heals… FUNimation Entertainment will release the series on DVD in half season sets in 2010. FUNimation Entertainment also announced that it has acquired home entertainment, broadcast and digital rights to the 12 episode action anime series “Sekirei” from Aniplex. Based on the manga of the same name only available in Japan, the anime is directed by Keizou Kusakawa. ABOUT SEKIREI Minato Sahashi is extremely intelligent, yet his inability to cope well under pressure has led to his failing the college entrance exam – twice. As a result he has been branded a loser. One day he meets a girl named Musubi as she is being chased by two bandits and his life changes forever. The girl runs but takes him with her and soon finds that Minato, while unknown to him, is an Ashikabi, one of the mysterious set of masters that can become partners with some of the 108 cute girls, buxom women, and bishonen called “Sekirei”. Their partnership will allow Minato to realize his true capabilities and his own strength. FUNimation Entertainment will release the series on DVD in 2010. Finally, FUNimation®\ Entertainment announced that it has acquired home entertainment, broadcast, digital and merchandise rights to the 24 episode sci-fi action anime series “Full Metal Panic!” and the 12 episode “Full Metal Panic? Fumoffu” sequel from Kadokawa Pictures, Inc. “Full Metal Panic!” is based on a series of novels by Gatoh Shoji. The first season of the series covers the first 3 novels, while the sequel, “Fumoffu,” covers various of the short stories. FUNimation has previously releases the third season, Full Metal Panic! The Second Raid. ABOUT FULL METAL PANIC! Sousuke Sagara is a seventeen-year-old military specialist working for the secret organization MITHRIL and has been recently assigned to protect the latest “Whispered” candidate: Kaname Chidori. Sousuke will have to deal with enemies from his past as well some surprising characters. Unfortunately for Sousuke, the toughest part of his mission isn't only protecting Miss Chidori but also getting used to living as an average high