Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

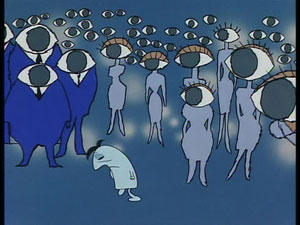

I'd like to think that the geek discourse has reached a point in its familiarity with Japanese pop media where Osamu Tezuka's (1928-1989) name is not only recognized, but bears more significance than simply the answer to the trivia question "who created Astro Boy?" With works like his black mooded sex-ed piece Apollo's Song and powerful religious dialogue Ode to Kirihito available in English, there's ample opportunity to see Tezuka as a creator whose ambitions extended beyond thoughtful children's works like Kimba the White lion. Personally, I've been a Tezuka fan since being deeply effected by his manga Adolf: A Tale of the Twentieth Century when I discovered it on a shelf at The Million Year Picnic a dozen years ago. After reading a large majority of the Tezuka manga available in English in the intervening years, I still found the Astonishing Work of Tezuka Osamu surprising. It's a stunning product of the forces that apparently drove Tezuka as a masterful artist and innovator. There's his experimentation; the drive to test a medium and stretch the limits of its ability to relate his stories. There's his social conscience; his willingness to address a matter like Vietnam in a work like Astro Boy, or dedicate a series like Black Jack to exploring his beliefs in medical ethics. And, because he was not the simple, idealized figure rendered in the caricatured artist in a beret, there's his competitiveness; his push to animate like Disney, to see that gekiga alterative, older audience work was drawing attention and jump onto the movement himself. Throughout the experimental animated shorts collected in the Astonishing Work of Tezuka Osamu, Tezuka is never at a loss for a social or artistic message. The artistic elements are as diverse as might be expected from almost three decades of test cases devised by a mind like Tezuka's. Each short is distinct from all others, and all are distinct from his manga. Other than a cameo by Astro Boy and rare appearances by his short-hand for breaking tension, the gassy, pig nosed gourd Hyoutan-Tsugi, the re-used templates found throughout his manga are absent from these animated works. Rarely do Tezuka's shorts look like an animated version of his manga the way that an Astro Boy or Kimba adaptation might. Instead, Tezuka displays a versatility that testifies to the fact that he was not stuck drawing the Disney/Fleischer-esqie cartoonishly stylized figures with which he is associated. North American manga discussion has often returned to the debate of whether that look is appropriate for Tezuka's more serious work. On one hand, it is criticized as being distractingly non-modern. From another perspective, the design is excused as being less important than the message, significance and other artistic merits of the work. Though the distinct look of Tezuka's short serve the purpose of that animation, I'd suggest that they argue for the success of his approach to manga. These experimental pieces demonstrate that Tezuka was neither dogmatically stuck on nor limited to the stylization he employed. As an artist who spent a career exploring and tailoring his work to media, his manga consistently worked with an approach to rendering people that he felt effectively conveyed their emotions and humanity. The experiments also possess a distilled quality that is unlike most Tezuka manga. While an image or page in a work of Tezuka manga rarely looked sloppy, stories often twist into overly complex convolutions due to what looks like a rush between the idea and the pen. In contrast, the effort to fit the experimental shorts into their intended structures give these works a sense of poetic order. Given the artistic demands and departure from comfortably familiar territory, the degree to which the shorts are narratively satisfying is a bit surprising. As is the vehemence of their social aspect. These works aren't simply Tezuka building and testing credibility as an animator. Nor, in most cases, are they Tezuka sharpening an odd corner into the edge of social critique as an afterthought. Tezuka's blunt assessment of the human species is pervasive and proves to be undulled over the decades span in which the shorts were produced. Watch them all across an afternoon, and they're liable to push a mood into "hide the sharp objects" territory. Tezuka's body of manga work often embraced both sides of a dichotomy. There was compassion for humanity and its perseverance, and at the same time, exasperation with crimes that the species committed against itself, and ways in which it hindered that push to survive. Where that manga tended towards a dialectic view of human nature, the shorts tend to be critical parables. In the lighter cases, he teases the point rather than jab it in, but, repeatedly, Tezuka highlights the disastrous leanings of humanity. This isn't so much an observation of inherent thanatos as it is pointing out the species' unthinking disregard for consequence. In The Astro Boy Essays, Frederik Schodt says "the first word usually associated with Tezuka and all of his work is hyumanizumu or 'humanism.' Most Japanese writers immediately seize upon this term and use it in either a positive sense (referring to Tezuka's love for humanity) or a derogatory sense (implying that he has an overly simple or naive view of human nature). Yet, in Japanese, as in English, humanism is an extremely vague term, and it is doubtful that most of those using it are aware of its sub-meanings." Tezuka was evidently keenly aware of the faults of humanity when producing his shorts. In their lighter moments, this results in bemused exasperation. In the darker ones, the observations are devastating. In their visual tinkering and in their philosophy, there is a wealth to consider and interpret throughout these experimental shorts.

Tezuka In Animation and Role of Experimental Shorts

Osamu Tezuka had been tenuously involved with anime such as Toei Doga's Alakazam the Great (1960), where his involvement was debatably overstated for publicity, but he began making his mark on the field in earnest when he introduced anime to Japanese TV with 1963's Astro Boy.

In 1961, he founded Tezuka Osamu Production, soon renamed Mushi Productions, with the intended business model of producing commercial anime to fund experimental works. Work began with 1962's Tales of the Street Corner, a statement of capability with a style and expression distinct from the output by Disney or Toei.

From that artistic declaration, he moved on with the plan to produce anime that would be inexpensive and profitable. He selected his most popular manga creation, Astro Boy, underbid in a deal with Fuji TV to establish a financial barrier of entry to potential competitors and began inventing a process for cheaply producing 25 minutes of animation weekly.

From Frederik L. Schodt's Astro Boy essays, one of the best English language discussions of the subject: "Without realizing it, Tezuka and Mushi Productions created the template for modern Japanese animation. What they started as a system designed to make animation on the cheap eventually became a challenge and provided a new way of telling a story. Instead of movement and "realism," the emphasis was place on story, character development and emotional impact."

Anime production, especially for Japanese TV, is still subject to the template that Tezuka laid out in his Fuji TV/Astro Boy deal. Roland Kelts in Japanamerica notes that the low-bit of roughly $3000 an episode for Astro Boy is referred to as "Tezuka's Curse."

In that it created an industry, it can't be said Mushi Production model's failed. Yet, it did not succeed in providing a profit engine for Tezuka's work. The studio became overstaffed, debt leveraged and after a string of boundary pushing but commercially unsuccessful movies that includes 1001 Nights, Cleopatra, and Belladonna of Sadness, Mushi went bankrupt in 1973. It was revived in 1977, at which point no it was longer Tezuka's company.

Beyond that, the template it produced was one in which sponsors often controlled purse strings and as such became the master of anime productions. Roland Kelts notes "The loss of financial and artistic control is an unavoidable part of Tezuka's legacy, complicating his reputation in Japan and frustrating (or infuriating) later generations of anime artists."

Experimental shorts represented a third course in the scheme of animation; neither adhering to the rules of a televised project or a theatrical one. Often self funded, these were statements and not products. With the advent of animation festivals, an audience did develop for these works, but they remained non-commercial project. Anime, and especially Tezuka anime, was already an exported product long before the boom of the late 90's, but the idea of producing shorts for a festival audience also allowed the work to be conceived for an international set of receptive viewers.

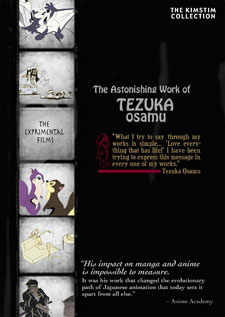

The Astonishing Work of Tezuka Osamu

Released by KimStim and Kino International

1. Tales of the Street Corner / 1962 / 16:9 / 39:04 / English Subtitles

Context: At this point in the history of the medium, anime was being produced in the form of movies, largely by Toei. Involved in that studio process, Tezuka contributed designs, concepts, storyboards and scripts, and in 1962, Tezuka had a writing credit on Sinbad No Boken. The launch of an Astro Boy tv series was still a year off.

2. Male / 1962 / 4:3 / 03:09 / English Subtitles

Context: Male was exhibited with the first episode of Astro Boy.

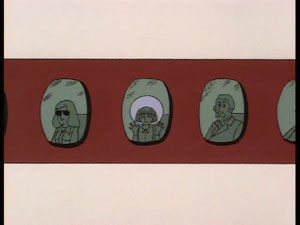

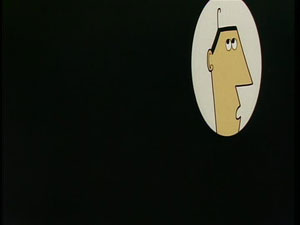

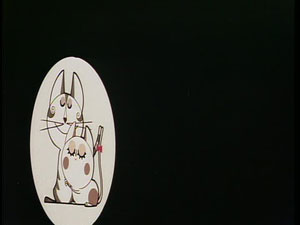

Based on Natsume Soseki's satire of the integration of Western ideas into Japanese society during the Meiji period, "Wagahai wa Neko de Aru ("I am a cat"), Male captures the action in oval apertures as an amorous cat comments on the woes of the man on the bed above him. The guy tries to smooth his cowlick. The cat cuddles with his lady love. The guy twiddles his thumbs, and smokes. The cat rolls his eyes. Ultimately the event for which the man had been waiting occurs and the short revealed something mature had happened - the kind of tragedy not to be found in a commercial animated movie of the age. Possibly, this could be considered the prototype of "anime - not for kids."

3. Memory / 1964 / 4:3 / 05:40 / English Subtitles

Context: Between the production of the last experimental short and this one, Tezuka had become a force in anime with the televised Astro Boy anime and the re-edited, colored Astro Boy: The Brave In Space movie.

4. Mermaid / 1964 / 4:3 / 08:17 / No Dialog

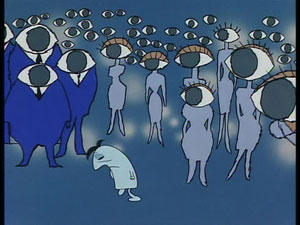

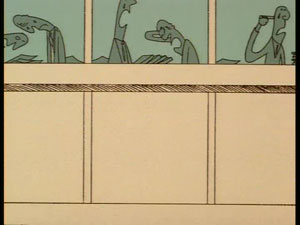

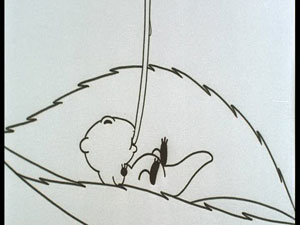

Tezuka's fascination with the subjective continues. This time the stylization is static and minimalistic.

The plot and context of Mermaid were compared by Tezuka's official site to Terry Gilliam's Brazil. In place of Memory's parades of the subjective, Mermaid features an imagination base instance of the mind externalized. A boy sees fish as mermaids. Though the short is animated with simple lines and small wave like motions, this mental rebellion constitutes a grave social break, for which there are equally grave consequences.

5. The Drop / 1965 / 4:3 / 04:18 / No Dialog

Context: Around 1965, Tezuka produced the manga and anime of Amazing Three, which featured Bokko, Nokko and Pukko, aliens sent to Earth who take the shapes of a rabbit a horse and a duck while judging humanities fitness to exist in the universe. Mushi reworked their anime production method to have animators working in parallel, with each drawing a different character. Amazing Three's (or Wonder Three) concept was later reused with Bremen 4: Angels in Hell (1981). Early in the decade (2000), Studio Pierrot and Digital Manga discussed staging an Amazing Three revival.

1965 also saw the premiere of Jungle Emperor Leo (aka Kimba the White Lion) - the first color TV anime series in Japan.

6. Pictures at an Exhibition / 1966 / 16:9 / 32:56 / No dialog

Context: In 1966, Tezuka's commercial work featured his return to the perennially popular Journey to the West epic with a new pilot film of Adventures of the Monkey King. Saiyuki/Journey to the West featured chaotic mythical primate Son Goku, who threw the Heavenly Kingdom into disarray before being subdued by Buddha and sent on the titular pilgrimage with the monk Xuanzang. Adventures of the Monkey King was criticized for presenting a bland Goku. When Tezuka reworked the pilot to produce the Goku's Great Adventures animated TV series (39 episodes, January 7, 1967 - September 30, 1967), the renewedly brasher, rebellious Goku provoked complains from the PTA.

1966 also saw the production of a pilot of proto-shoujo Princess Knight, the manga of which ran 1953-56 and 1963-66. A year later, the Princess Knight TV series would arguably become the first Japanese anime program aimed at girls. The series followed a girl, raised as a boy to protect her kingdoms throne, who adopts the third identity of the "Princess Knight" to fight for justice. Gender themes evoked here would later become a touch stone as women began becoming prominent writers of shoujo with the ascendance of figures like Riyoko Ikeda ( Rose of Versailles), Moto Hagio (They Were 11, To Terra) and the Year 24 Group

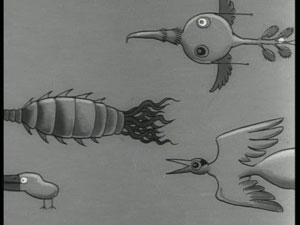

7. The Genesis / 1968 / 4:3 / 04:02 / English Subtitles / B&W

Context: 1968 was a busy year from the prime of Tezuka's career. There was a manga and pilot of Gum Gum Punch: a young children's work featuring a brother and sister given a gift from the god of gum that could be used to produce anything they need, along with the help of disciple Gum Gum. Likewise a manga and a pilot were produced for Prince Norman - a sci-fi concerning a conflict between aliens and super powered humans. According to Tezuka's site, the story was a reaction to how the Japanese student protest movement of the time had been reverberating through society, spawning children's manga that Tezuka judged to be too violent.

A pilot was produced for Dororo, his story of a swordsman with an artificial body questing after the yokai who came to possess his natural organs. This pilot adhered closely to the manga, and unlike the low budget, monochrome TV series that would air the following year, it was produced in color.

On the manga side of his work, Tezuka began Yamato, third part of his life's work, the Phoenix cycle, which chronicled a tragedy of authoritarian rule in 5th century Japan.

This was also the year in which Tezuka addressed changing social tides in Swallowing the Earth (featured in detail here).

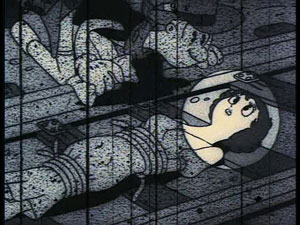

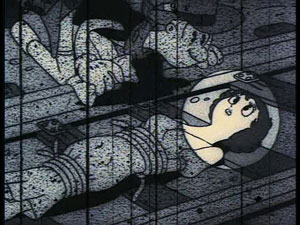

8. Jumping / 1984 / 4:3 / 06:22 / No Dialog

Context: In 1984, Tezuka conceived and directed TV anime movie Bagi: the Monster of Mighty Nature in order to address what he felt to be the issue of the moment - government approval of research into the use of recombinant DNA. Its concept of a rebellious young man and a pink puma woman produced by modified DNA might seem at home among modern anime, but its approach and its opinion are distinctively, and in some aspects, disturbingly Tezuka.

1984 was also the half way point in the serialization of Tezuka's painful historical Adolf. Released by Viz and out of print, Tezuka invents the story of Adolf Kaufmann a half German, half Japanese boy and Adolf Kamil, a Jewish boy living in a Japanese exile Jewish community starts before World War II and progresses through the 20th century.

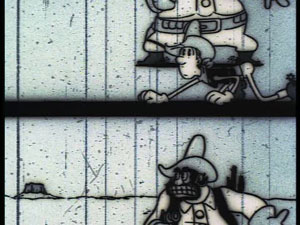

9. Broken Down Film / 1985 / 4:3 / 05:42 / No Dialog / B&W

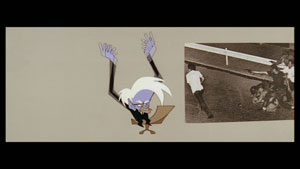

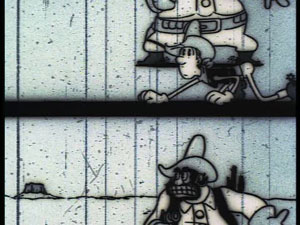

Largely a concept goof, Broken Down Film appears to be philosophically lightest short in the collection. While there is an aspect of meta commentary concerning the effect of time's passage on art, the presence of a social message is difficult to detect.

The tied to the tracks film is backdated to 1885. Set to the tune of Snake Rag, a Max Fleischer-esque rendering of a fearless white hat ranges into the scrub to rescue his lady fair from a grizzled brute.

The film stock looks terrible. It's scratched. Hardly a speck is free of artifacts.

Then, all of a sudden, hero and horse become entangled in a mass of the crud that had been screwing up the film. Soon, the fourth wall is as broken down as the film. Artifacts are being wiped away by the hero in order for him to see more clearly... speech balloons are being grabbed and tossed... patches in the film are being used to bushwhack foes.

I wonder if Broken Down Film was prompted by responses to Tezuka's work the likes of which have been seen from North American manga readers. It's the "looks old" knock, in which noting the age of a work becomes the primary observation - Black Jack or Phoenix don't look like modern manga, therefore they can't be taken seriously. Here, Tezuka reappropriates the criticism and turns it into a joke. He then does a double twist, looking into something more current before being yanked back, then finally, getting caught up and stumbling in the age degradation.

10. Push / 1987 / 4:3 / 04:16 / English Subtitles

Context: This is late in Tezuka's career, and the point at which his death of stomach cancer on February 9, 1989 seems to have lamentablely cut short a still evolving body of work. 1987 was the mid point of his work on the last complete chapter of the Phoenix cycle, Sun. This one featured a faith based conflict between aboriginal gods and Buddhism. 1987 also marked the beginning of his incomplete follow-up to his manga biography of Buddha, Ludwig B.

11. Muramasa / 1987 / 16:9 / 08:42 / No Dialog

Context: From 1987 to 1989 Tezuka worked on the Gringo, the unfinished, posthumously published look at politics and commerece, related in the story of an exiled corporate officer entangled in the agenda of a group of guerillas.

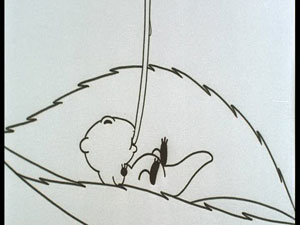

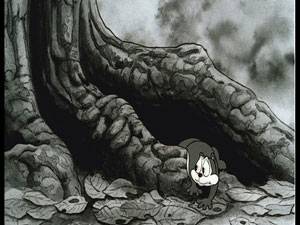

12. Legend of the Forest / 1987 / 16:9 / 29:25 / No Dialog

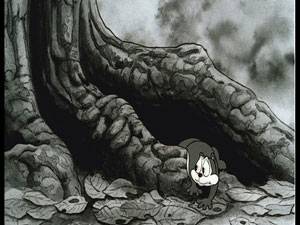

Inspired by Tschaikovsky's fourth symphony Op. 36, the first and fourth of a planned four part movement were finished. Visually, the Fantasia like piece aimed to capture the history of animation, and its evolution from a theatrically focused medium to one targeted to TV.

If Tezuka's work had continued past the Cold War, ecology might have replaced war as the primary bête noire of his productions. Manga such as Black Jack addressed it as an unappreciated threat, and in Legend of the Forest, it becomes the narrative theme.

13. Self Portrait / 1988 / 0.13 / No Dialog

Context: In response to an animated project falling through, Tezuka wrote the manga Neo-Faust, his third direct retelling of the legendary deal with the devil.

For The Sake Of Completeness...

The Astonishing Work of Tezuka Osamu not include Cigarettes and Ashes (1965). The three minute short features a chicken launch a war against its human oppressors.

The experimental short Party was not completed, but the short gag was to have looked an animator alone with his creations,

Mosquito, as envisioned late in his career, and the uncompleted short was to have looked to reconcile differences between film and animation.

The tribute Essays On Insects (13 minutes, August 3, 1995) presented five shorts adapted from Tezuka's "Essay in Idleness of Insects" in the spirit of his experimental work.

Ain't It Cool News Animation RSS Feed

1. Tales of the Street Corner / 1962 / 16:9 / 39:04 / English Subtitles

Context: At this point in the history of the medium, anime was being produced in the form of movies, largely by Toei. Involved in that studio process, Tezuka contributed designs, concepts, storyboards and scripts, and in 1962, Tezuka had a writing credit on Sinbad No Boken. The launch of an Astro Boy tv series was still a year off.

2. Male / 1962 / 4:3 / 03:09 / English Subtitles

Context: Male was exhibited with the first episode of Astro Boy. Based on Natsume Soseki's satire of the integration of Western ideas into Japanese society during the Meiji period, "Wagahai wa Neko de Aru ("I am a cat"), Male captures the action in oval apertures as an amorous cat comments on the woes of the man on the bed above him. The guy tries to smooth his cowlick. The cat cuddles with his lady love. The guy twiddles his thumbs, and smokes. The cat rolls his eyes. Ultimately the event for which the man had been waiting occurs and the short revealed something mature had happened - the kind of tragedy not to be found in a commercial animated movie of the age. Possibly, this could be considered the prototype of "anime - not for kids."

3. Memory / 1964 / 4:3 / 05:40 / English Subtitles

Context: Between the production of the last experimental short and this one, Tezuka had become a force in anime with the televised Astro Boy anime and the re-edited, colored Astro Boy: The Brave In Space movie.

4. Mermaid / 1964 / 4:3 / 08:17 / No Dialog

Tezuka's fascination with the subjective continues. This time the stylization is static and minimalistic. The plot and context of Mermaid were compared by Tezuka's official site to Terry Gilliam's Brazil. In place of Memory's parades of the subjective, Mermaid features an imagination base instance of the mind externalized. A boy sees fish as mermaids. Though the short is animated with simple lines and small wave like motions, this mental rebellion constitutes a grave social break, for which there are equally grave consequences.

5. The Drop / 1965 / 4:3 / 04:18 / No Dialog

Context: Around 1965, Tezuka produced the manga and anime of Amazing Three, which featured Bokko, Nokko and Pukko, aliens sent to Earth who take the shapes of a rabbit a horse and a duck while judging humanities fitness to exist in the universe. Mushi reworked their anime production method to have animators working in parallel, with each drawing a different character. Amazing Three's (or Wonder Three) concept was later reused with Bremen 4: Angels in Hell (1981). Early in the decade (2000), Studio Pierrot and Digital Manga discussed staging an Amazing Three revival. 1965 also saw the premiere of Jungle Emperor Leo (aka Kimba the White Lion) - the first color TV anime series in Japan.

6. Pictures at an Exhibition / 1966 / 16:9 / 32:56 / No dialog

Context: In 1966, Tezuka's commercial work featured his return to the perennially popular Journey to the West epic with a new pilot film of Adventures of the Monkey King. Saiyuki/Journey to the West featured chaotic mythical primate Son Goku, who threw the Heavenly Kingdom into disarray before being subdued by Buddha and sent on the titular pilgrimage with the monk Xuanzang. Adventures of the Monkey King was criticized for presenting a bland Goku. When Tezuka reworked the pilot to produce the Goku's Great Adventures animated TV series (39 episodes, January 7, 1967 - September 30, 1967), the renewedly brasher, rebellious Goku provoked complains from the PTA. 1966 also saw the production of a pilot of proto-shoujo Princess Knight, the manga of which ran 1953-56 and 1963-66. A year later, the Princess Knight TV series would arguably become the first Japanese anime program aimed at girls. The series followed a girl, raised as a boy to protect her kingdoms throne, who adopts the third identity of the "Princess Knight" to fight for justice. Gender themes evoked here would later become a touch stone as women began becoming prominent writers of shoujo with the ascendance of figures like Riyoko Ikeda ( Rose of Versailles), Moto Hagio (They Were 11, To Terra) and the Year 24 Group

7. The Genesis / 1968 / 4:3 / 04:02 / English Subtitles / B&W

Context: 1968 was a busy year from the prime of Tezuka's career. There was a manga and pilot of Gum Gum Punch: a young children's work featuring a brother and sister given a gift from the god of gum that could be used to produce anything they need, along with the help of disciple Gum Gum. Likewise a manga and a pilot were produced for Prince Norman - a sci-fi concerning a conflict between aliens and super powered humans. According to Tezuka's site, the story was a reaction to how the Japanese student protest movement of the time had been reverberating through society, spawning children's manga that Tezuka judged to be too violent. A pilot was produced for Dororo, his story of a swordsman with an artificial body questing after the yokai who came to possess his natural organs. This pilot adhered closely to the manga, and unlike the low budget, monochrome TV series that would air the following year, it was produced in color. On the manga side of his work, Tezuka began Yamato, third part of his life's work, the Phoenix cycle, which chronicled a tragedy of authoritarian rule in 5th century Japan. This was also the year in which Tezuka addressed changing social tides in Swallowing the Earth (featured in detail here).

8. Jumping / 1984 / 4:3 / 06:22 / No Dialog

Context: In 1984, Tezuka conceived and directed TV anime movie Bagi: the Monster of Mighty Nature in order to address what he felt to be the issue of the moment - government approval of research into the use of recombinant DNA. Its concept of a rebellious young man and a pink puma woman produced by modified DNA might seem at home among modern anime, but its approach and its opinion are distinctively, and in some aspects, disturbingly Tezuka. 1984 was also the half way point in the serialization of Tezuka's painful historical Adolf. Released by Viz and out of print, Tezuka invents the story of Adolf Kaufmann a half German, half Japanese boy and Adolf Kamil, a Jewish boy living in a Japanese exile Jewish community starts before World War II and progresses through the 20th century.

9. Broken Down Film / 1985 / 4:3 / 05:42 / No Dialog / B&W

Largely a concept goof, Broken Down Film appears to be philosophically lightest short in the collection. While there is an aspect of meta commentary concerning the effect of time's passage on art, the presence of a social message is difficult to detect. The tied to the tracks film is backdated to 1885. Set to the tune of Snake Rag, a Max Fleischer-esque rendering of a fearless white hat ranges into the scrub to rescue his lady fair from a grizzled brute. The film stock looks terrible. It's scratched. Hardly a speck is free of artifacts. Then, all of a sudden, hero and horse become entangled in a mass of the crud that had been screwing up the film. Soon, the fourth wall is as broken down as the film. Artifacts are being wiped away by the hero in order for him to see more clearly... speech balloons are being grabbed and tossed... patches in the film are being used to bushwhack foes. I wonder if Broken Down Film was prompted by responses to Tezuka's work the likes of which have been seen from North American manga readers. It's the "looks old" knock, in which noting the age of a work becomes the primary observation - Black Jack or Phoenix don't look like modern manga, therefore they can't be taken seriously. Here, Tezuka reappropriates the criticism and turns it into a joke. He then does a double twist, looking into something more current before being yanked back, then finally, getting caught up and stumbling in the age degradation.

10. Push / 1987 / 4:3 / 04:16 / English Subtitles

Context: This is late in Tezuka's career, and the point at which his death of stomach cancer on February 9, 1989 seems to have lamentablely cut short a still evolving body of work. 1987 was the mid point of his work on the last complete chapter of the Phoenix cycle, Sun. This one featured a faith based conflict between aboriginal gods and Buddhism. 1987 also marked the beginning of his incomplete follow-up to his manga biography of Buddha, Ludwig B.

11. Muramasa / 1987 / 16:9 / 08:42 / No Dialog

Context: From 1987 to 1989 Tezuka worked on the Gringo, the unfinished, posthumously published look at politics and commerece, related in the story of an exiled corporate officer entangled in the agenda of a group of guerillas.

12. Legend of the Forest / 1987 / 16:9 / 29:25 / No Dialog

Inspired by Tschaikovsky's fourth symphony Op. 36, the first and fourth of a planned four part movement were finished. Visually, the Fantasia like piece aimed to capture the history of animation, and its evolution from a theatrically focused medium to one targeted to TV. If Tezuka's work had continued past the Cold War, ecology might have replaced war as the primary bête noire of his productions. Manga such as Black Jack addressed it as an unappreciated threat, and in Legend of the Forest, it becomes the narrative theme.

13. Self Portrait / 1988 / 0.13 / No Dialog

Context: In response to an animated project falling through, Tezuka wrote the manga Neo-Faust, his third direct retelling of the legendary deal with the devil.