Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

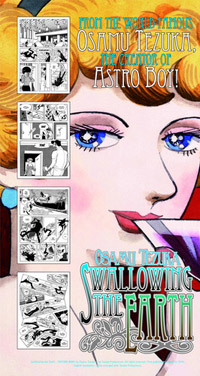

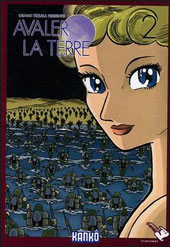

Manga Spotlight: Swallowing the Earth By Osamu Tezuka Released by Digital Manga Publishing Preview Available Here

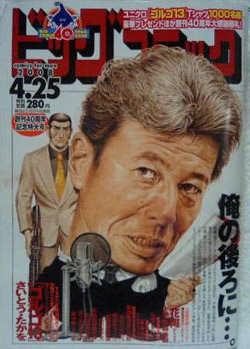

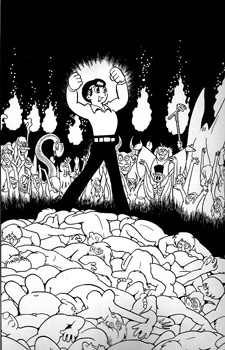

Otaku USA editor in chief Patrick Macias recently twittered a recommendation of "God of Manga" Osamu Tezuka's meeting of Highsmith and political outrage thriller Mw, saying of it "Tezuka's "serious" works are unspiriling coils of contrivance, wild shifts of tone, and implausible plots. In short, MANGA." Written in 1968, 8 years before Mw, Swallowing the World exhibits those qualities in an even rawer, more untested manner. Tezuka's imprint is chiseled into the profiles of anime and manga. He created crucially popular boy robot Astro Boy. He was instrumental in establishing many of the visual and genre foundations of manga storytelling. With Mushi Production's development of an Astro Boy anime, he laid out a template that still influences how anime is made. Manga was certainly the canvas for an audacious god, and while Tezuka's work was not always artistically or commercially successful, it was always illuminated by the spark of his brilliant creativity. Over 515 pages, Swallowing the World sees Tezuka furiously working through an attempt to tell a mature audience story that would field test an array of thematic and visual experiments. Frankly, it is a convoluted mess. However, as confused and unsettled as it remains over that giant page count, Swallowing the World is a mess the likes of which you'll only find in manga/comics and only from someone like Tezuka. As such, I'm unequivocally glad I read it. While I doubt that Swallowing the World was ever thought of as a well focused venture, a modern perspective brings its tempestuousness into focus. In it's preposterous over-inflation, Swallowing the World bolts a humanist treatise onto a plot with extravagance that would take the combined excess of a Moore James Bond flick and Kingdom of the Crystal Skull to measure against. That's before Tezuka's mind really starts whirling with inspired leaps and combinations, as he pulls in elements of pulp, mythologizes and pursues Twilight Zone digressions. Tezuka has produced convoluted stories in which the narrative knots are an intentional, involving element of the narrative. Here, he hasn't laid out a plot Rube Goldberg chain. In the case of Swallowing the World, the unmanaged coils of story are symptomatic of how the manga developed. Context, both social and creative, are crucial in this work of manga, whose meta-pleasures derive from watching an artist boiling over in the flames of creative stimuli. In 1942, on Guadalcanal Island Japanese officers Adachigahara and Seki track down and execute an escaped American POW. As he dies smiling in a field of flowers, the American holds out the photograph of an unimaginably beautiful woman and utters the name "Zephyrus".A shadow cadre of women bearing torches move in procession to a glass coffin. These women swear to their mother that they will exact revenge by bringing about global upheaval. With this promise, Swallowing the Earth introduces the "goddess" Zephyrus' decades long plan to realize a deathbed proclamation. "First money! If money controls mankind, robbing them of their freedom and happiness, I want you to destroy it!" "Next law! However possible, bring the law and moral codes throughout the world into utter chaos!" "And finally... MEN! Look down on all the men of the world with the scorn and ridicule they deserve! And do not even dream of marrying one!" More than two decades pass, when the manga returns to Adachigahara and Seki in 1966. Neither man has given up their yearning for glimpsed Zephyrus. However, while Seki has lived a content life as a laborer, Adachigahara has risen to become a captain of industry amidst Japan's swelling post recovery strength. Never finding satisfaction in worldly success, Adachigahara has clung to his hopes of locating the mystery woman of his dreams. In that pursuit, Adachigahara visits the cramped living space of his former comrade, hoping to enlist Seki's son as a proxy in his quest. As noted in the now offline official English Tezuka World site, Zephyrus' inspiration could be rephrased as a condemnation of selfishly pursuing objects of desire: women, money and political power - the kind of obsessions men like Adachigahara caricature. Counter intuitively, the title "Swallowing the Earth" is not a direct reference to Zephyrus' campaign to shatter social order. It's the philosophy of the younger Seki, Gohonmatsu. This good natured goon looks like he wandered into the manga off a golden age newspaper comic strip. Many reviewers have mentioned Popeye, but I'm inclined to agree with Frederik Schodt's Li'l Abner comparison for Gohonmatsu. He's a folksy figure who might have wandered out of an idealized, pre-industrial past. With hands in his pockets, the towering young longshoreman simply smiles down at the world around him. While petty desires, greedy impulses and vengeful determination buzz past him, Gohonmatsu Seki simply aims to gulp down as much alcohol as possible. This isn't a noble or heroic motivation for the guy who is ostensibly the manga's protagonist. However, despite his herculean buffoonishness, there is a Zen quality to Gohonmatsu's humility and satisfaction with labor. While he stands in opposition to Zephyrus' plan to turn the world upside down, his rejection of women, money, and prestige exemplify the results of her aims. Laying on further ironies, the physical, male lead is swept up and tossed by the plot's storms, serving as the object as much as the subject of the action. So, scorching revolutionary set against a detached, but determined free spirit...sounds like a reasonably intelligent dialectic? Except, in order to build that discussion, Tezuka stitched together a Frankenstein's Monster out of World War II tableaus, current event hot buttons, matinee highlights and satirical absurdity. Melodrama concerning selling scientific research to the Nazis in 1940 Lyon takes an Indiana Jones leap for a resolution on the South Pacific island ruins of the lost empire of Moo. Conceit is layered on conceit. Some are uneasy fits for a subject intended to be taken seriously, such as pulp secondary revenge plots along the lines of what you'd expect from a Batman villain. Others have not aged well, such as Zephyrus' use of LSD. Then, there are elements that are presented seriously in some instances, but also used as fodder for broad lampooning, such as a plot-crucial synthetic substance which, in one comedy scene, is excreted onto the faces of individual via tuches like spouts. Immortalized in his self cartooned image of the artist in a beret, it's easy to latch onto an idealized notion of Osamu Tezuka as a patron saint of manga. As might be expected, the reality was more complex, and Swallowing the Earth is caught up in the rip currents of the energies that fueled Tezuka's production of over 80,000 pages of manga over his life time. He was competitive. He was politically opinionated, but reluctant to be with associated concrete political statements. Tezuka's less admirable qualities as well as his brilliance leave their marks over Swallowing the Earth. From April 1968 to July 25, 1969 Swallowing the Earth appeared serially in Shogakukan 's "Big Comic" Big Comic is home to Golgo 13, a manga that is strictly sex and violence, and which takes absurd shots at various historical hot-points. For example, Viz's best of Golgo 13 collections include the titular assassin taking out Saddam Hussein's super-gun ballistics program, killing Princess Diana's lover shortly before her real death, jumping into the 1981 assassination attempt against the pope, and the like. Later Big Comic manga included the works of Naoki Urasawa (Monster), Hideo Yamamoto (creator of Ichi the Killer), Taiyo Matsumoto (Tekkon Kinkreet), Junji Ito (Tomie) and Ryoichi Ikegami (Sanctuary, Strain). (Correction: this later list of writers consists of contributors to spin-off Big Comic Spirits and not the long running Big Comic itself.) From the Big Comic description in 1996's Dreamland Japan by Frederik L. Schodt, a writer who is renowned for his work popularizing Tezuka in the English speaking world, who also pens the introduction to Swallowing the World. Big Comic: The grand-daddy of the Big family, Big Comic serializes works by big-gun artists. Long running stories have included the famous Golgo 13, by Takao Saito, about a Zen like professional assassin who always gets his mark; Hotel by Shotaro Ishinomori, about the inner workings of hotel life; and the gag strip Akabe-ei, by Hiroshi Kurogane. Don't look for sex and titillation here, though. This is serious stuff, written mainly by men over fifty and read by a faithful but aging male readership mostly over thirty.... Ads are scarce and are mainly for cars, marriage services, energy drinks, hair tonics, hair pieces, and so forth. In 1968, Big Comic was new and being read by young men. Shotaro Ishimori's chambara mysteries Sabu & Ichi's Arrest Warrant was moving to the anthology. Golgo 13 would commence half way through the run. Tezuka was not always the innovator of the scene, and Swallowing the Earth represents his attempt to jostle his way into the forefront. Even Zephyrus herself stands as a hallmark of how Tezuka was appropriating and repurposing then popular touch points. She becomes a Tezuka character, entering his "star system" retinue of cast templates with later appearances in Black Jack, Phoenix: Karma, and Unico. However, as noted by Schodt, her style of a buxom, free spirited blonde was a popular character type of her day. In the mid 60's Tezuka had recently completed the three year run of the original Astro Boy anime. He had worked on the second version of Princess Knight, a fairytale about a princess with male and female hearts that introduced or popularized themes that would later be developed when the Year 24 group revolutionized girls audience shoujo manga written by women. He had commenced working from the beginning of history and the end of humanity in his magnum opus, Phoenix. He was also still producing serial adventure manga for younger audiences. Some were dark and interesting, like the supernatural adventure Dororo (partially a reaction to popular monster manga like Shigeru Mizuki's GeGeGe No Kitaro). Others were a bit questionable: Amazing Three - the story of Bokko, Pukko and Nokko - aliens who come to Earth and transform into a rabbit, a duck and a horse; Ambassador Magma - a giant robot sci-fi in which Tezuka was sufficiently busy to require Inoue Tomo and Fukumoto Kazuyoshi assist the manga; and my favorite example of Tezuka's fallibility, Big X - manga concerning a boy who injects a drug to become Nazi super weapon Big X. And, perhaps the best evidence that Tezuka was going through an experimental period in those post Astro Boy years is Vampires (serialized in "Weekly Shonen Sunday" June 12, 1966 to May 7, 1967). From Tezuka World's description on the manga. In this unconventional work, a boy named Toppei who can transform himself into a wolf is the main character. The story begins when one day Toppei visits Mushi Productions, an animation production company, and persuades President Tezuka Osamu to hire him. Toppei, who actually belongs to a vampire tribe whose members transform themselves into wolves, has come to Tokyo to look for his missing father. The villain of the story, named Rock, discovers Toppei's secret, and then tries to plot against Toppei. In the meantime, Toppei's tribe, which has long been oppressed by human beings, secretly plans a revolution against them. Toppei and Tezuka Osamu try to stop the revolution; Rock tries to use it to the advantage of his own wicked designs; and then the police get involved. Everyone's intentions got entangled, and Toppei is in danger of being cornered. (Additional information about Vampires can be read here) Visually, Tezuka's aggression yields some spectacular results throughout the course of Swallowing the World. From his early days, Tezuka rejected stagey manga, in which characters and action are presented front, center. To see Tezuka's interpretation of manga as stage play, see Phoenix Volume Eight, which features an in manga performance of Robe of Feathers. Instead, he looked to how cinema and animation framed their subjects. In Swallowing the Earth, he went further and invented new grammar for manga. On a single page, a couple is shown falling in love through rectangular boxes vertically aligned against a black background. The boxes shrink and zoom as the view gives the couple privacy, moving from them to the flowers in a surrounding garden, then a butterfly on one of these flowers. Then, on the same page, a white text caption breaks the privacy and the view jumps to larger and larger images of embracing arms atop a bed. Tezuka was one of the great minds of the medium. He knew how to break convention. In Swallowing the World, he did it judiciously, emphasizing significant events. Whether or not you're a student of the medium, there's something to be appreciated there. In terms of developing a long term narrative for an adult audience, Tezuka was getting his sea legs. He was able to direct a causal channel throughout the cascading events, larger and more connected than his serial adventures. However, he then fails to make any sensible route for navigating that course. Tezuka World notes that he was undecided as to whether he should publish it as a long story or as a collection of independent shorts. To Swallowing the World's detriment, it never settles down structurally and tonally. As Tezuka changes the subject, one is libel to neither lead into nor complement the next. Major characters are introduced at the 11th hour while others come and go as the muse strikes Tezuka. While North American readers look for manga that reads well in a trade paperback collection, in the case of Swallowing the World Tezuka evidentially struggled with grafting a novelistic approach to manga with its serialized origin, or even whether novelistic manga was what he wanted. Beyond Tezuka's ambivalence towards Swallowing the Earth's narrative structure, the manga is swept up in the wildness of social change. No one needs an online anime and manga columnist to tell them that we're in the midst of tumultuous times. Works like Swallowing the World demonstrate how, sooner or later, this cultural moment bound going to inspire some heady media. 1968 found Japan in the midst of a metamorphosis. With the economic engine primed, the finical pendulum was on the other side of its current swing. The conflict in Vietnam was heating up. So was Japan's student protest movement. Across the globe Martin Luther King, Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. Tezuka had plenty of forces to grapple with, and in Swallowing the Earth, it feels like he was in a rush to comment on the changing society. Relating a parable of greed and mistreatment to comment on Japan's economic ascendance was within his comfort zone. Yet, Japan's student protest movement was too close and too specific to work its way into a Tezuka manga. As noted in Schodt's The Astro Boy Essays: Osamu Tezuka, Mighty Atom, Manga/Anime Evolution, though he loved media attention, Tezuka was reluctant to publically address or be associated with politics. The one notable exception was the Vietnam War, which he spoke against directly and through Astro Boy. This aversion to direct political involvement stood in contrast to the then younger animators like Hayao Miyazaki, and even more to the generation of student protesters who'd later become animators and manga artists themselves (such as Mamoru Oshii). Conversely, America's unrest had the distance to permit being evoked directly. From an American viewpoint and decades of perspective, Tezuka's use of charged caricatures and unnuanced handling of issues can be read as dated, bordering on offensive. Passages now seem closer to an Eddie Murphy SNL skit than the well formed development of a thesis. Tezuka's humanist sentiments are far from intentionally racist, but at the same time, his far gaze for material from which to draw lands him in some trouble. Swallowing the World finds the Prospero of anime and manga raising an unrelenting storm, gusting with Tezuka's attempt to raise a long form adult parable to crash against his political sentiments. It's literally awesome. The magic of watching Tezuka weave together diverse inspirations are also the manga's curse as it turns confused to a fault. It's not a well formed story, but it is a breathtaking performance. Forty years after the fact, Swallowing the World still glows with the creative energies that produced it.