Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Manga Spotlight: Azumanga Daioh: The Manga: The Omnibus By Kiyohiko Azuma Released By ADV Manga

As far as manga goes, ADV'S omnibus collection of Azumanga Daioh tops the list of gift ideas for any recipient, regardless of whether they are fans of Japanese comics. It's not one of the great epics or the great dramas of the tradition. It's not a testament to manga's capabilities. Where Azumanga Daioh shines brighter than just about any other manga is that, like Azuma's Yotsuba&!, you can crack the book open to any page and find a moment of charming nostalgia that is sure to elevate your mood. 686 pages of four panel comic strips (yonkoma), in, what for a North American audience is an oversized, 9" x 6.4" is a large stack of manga, and one that is suitable for random reading or losing a sizable chunk of time tracking the story's simple progression. Azuma innovates the well-worn field of high school comedy manga by paring it down to a point where it is just the characters in their familiar stage of life. Rather than building boy meets girl or any other combination of romantic relationships, Azuma simply distills a collection of fond moments. At their most exciting, these are "remember when..." stories. It's five girls, a few of their other friends, their homeroom/English teacher, their PE teacher, and that's about it. No boyfriends or extracurricular endeavors. Except maybe for some largely off-panel drama during its conclusion, the manga never really inhabits times where these characters struggle. Instead, it skims their high school careers through the moments that will later be remembered fondly: the times before school or between periods, the mid-class lulls, the vacations and the festivals. Even if the general consensus might be that if high school or college is the best time of your life, you've backed yourself into a pretty unfulfilling situation, Azumanga Daioh does credibly catalogue the nice moments that make those times special. While an essential key to Azumanga Daioh's appeal is an absence of bitterness, it is not entirely an over idealized retrospective of school days. There is a light Charlie Brown sense of limitations, and there is a poignancy the builds from the notion that youth and high school lifeare ephemeral. The protagonists' high school careers discernibly advance as the series progresses. One year passes into the next and by the end of the collection, everyone is graduating. Consequently, as simple and pleasant, and largely escapist as Azumanga Daioh is, unlike some of the problematic manga whose purpose is to offer a gently relaxing situation, this manga is not reductive or regressive. Azumanga Daioh was originally serialized in the anthology Dengeki Daioh,a periodical for seinen, older-male audiences. To a North American reader, Dengeki Daioh's series, which include Gunslinger Girl,Figure 17, Please Teacher/Please Twins, Strawberry Marshmallow, Kasimasi ~Girl Meets Girl~, Di Gi Charat, and Kamichu might seem intended for other audiences, that are younger or female. There is a wide avenue for steering off course in this arena. The approach is open to situations where one can scratch the surface on a work largely concerning female characters, think about it, and find that the mindset is in fact very male oriented. Azuma himself veered in that direction with Wallaby, a manga that ran concurrently to early Azumanga Daioh about a boy who dies and is given a new life as his female classmate's stuffed wallaby. Yet, in the case of Azumanga Daioh, Azuma side-steps the issue. These are young women written by a male, they do note each other's bust size and there is an emphasis on non-threatening cuteness, but, they are still young women on their own terms. With only one named male peer and a leering, gape jawed classics teacher who is spun as a golden hearted eccentric, empowerment is not included in the equation. Azuma fits together a selection of opposing character types that are arranged as complementary, opposing forces. Boundless energy, unrestrained by judgment versus slightly cynical alertness. Zoned out, spacey versus successfully intelligent. Introverted versus competitive. At the same time, because he is working in this genre, his manga picks up the suggestion of its baggage. Grouping the characters together, what initially stands out is that someone is tiny and cute, some one is tall and busty, some one is tanned, someone has glasses. At first glance, it's the "something for everyone" standby. So many shonen and senein manga have put together female casts to cover the broad permutations of what character types a male reader might want to look at, that, if you are a steady manga reader, it's hard to look at a snap shot of Azumanga Daioh without thinking of the dating-game model of storytelling. Azuma takes about 50 pages worth of strips to refine the style of illustration, introduce the complete cast and settle on the finer details of how the cast relates to each other. By the end of that coalescing period, the characters have taken on a life of their own. A thorough map of how each character thinks is quickly developed. Azuma doesn't reveal every personal detail about anyone, but he does spell out their likes and dislikes, aptitudes, economic standing, and what makes them react. With these well shaded dimensions, the cast becomes memorable. They are not astonishingly interesting people individually, but it is entertaining to watch them play off each other. If you were in the same restaurant as the group of friends, you might not listen to their conversation, at some point, you attention would likely be piqued to glance at what they were doing from across the room. There's a formula for four panel strips that starts with a situation being presented in panel one and a results of that situation being executed in panel four. Azumanga Daioh finds success in working with the mechanistic nature of the format. Azuma feeds in casual situations, where the involved parties can be themselves. The other input is a cast of characters who are memorable, likable, and given to predictable behavior. In this case, "predictability" becomes a positive attribute. Panel one presents the subset of the cast involved and the topic. Panel four exploits the situation, playing off some running gag/character attribute. Panel one: student watches English teacher converse with struggling foreigner. Panel four: the teacher bolts past the student exclaiming "No Good! He's German!" Panel one: cute student shows ADHD student her prized autograph. Panel four: cute student is in tears after ADHD student pretended to throw the autograph out a window. It's a simple system, but Azuma consistently builds laugh out loud funny gags with it. Panel one: during a sleep-over, spacey student rummages in a kitchen cupboard, with a thought bubble image of waking sleepers up by banging on a frying pan. Panel four: spacey student walks out the kitchen with a carving knife gripped in her hand.

Anime Spotlight: School Rumble Volumes 1 - 3 Released by FUNimation

Shinji Takamatsu directs a competent, if slightly uninspired, adaptation of Jin Kobayashi's surprisingly charming manga, and like that source material, the anime comfortably accepts it's limitations. After being strip mined in work like Love Hina, the young male audience (shonen) high school love triangle may have been exhausted as a storytelling platform. Many of the newer works are perfectly fine for some one experiencing the plot for the first time, but decades after Kimagure Orange Road and Urusei Yatsura, the genre shows signs that it has moved into a position that defies reinvigoration. Zany has been done. Parody has been done. Nice has been done. However, if the shonen love triangle remains a well inhabited derelict structure, School Rumble simply has fun by running down its corridors. In presenting a situation that is humorously over-complex without trying to outdo or comment on previous entries, School Rumble's winning appeal is in that the series is open and unbowed in the face of "been there, done that." That benifit doesn't result an appeal that is quite as broad as Azumanga Daioh's; you do have to be a fan of comedy anime/manga to appreciate it. But, school Rumble does not require a commitment to or even an acceptance of the conventions of shonen relationship plotting. There's an agreeable contrast in a relationship comedy series that doesn't ask its viewer to love it's characters or invest any emotional capital in their endeavors. The first episode of School Rumble features the protagonist holding up a copy of Sun Tzu's Art of War, as if to declare the commencement of a no prisoners, all out battle royale for the affections of the person to whom she is enamored. Instead "know thyself as thine enemy and a hundred victories are yours" turns into an embarrassing vision of self deprecation. Instead of fierce conniving, the struggle is more akin to a blind stumble for the light switch than a tooth an nail scramble. While diagramming the situation results in a ferocious tangle of relationships, the truth of it is more along the lines of A loves B. B is oblivious to A's interest. B loves C. C is disinterested in everyone. Tenma is a puppy-cute girl who can hardly do a thing right, to the point where she relies on her younger sister Yakumo for just about everything. And, Tenma is hopelessly obsessed with Karasuma. Tenma doesn't have competition with other people for the affection of Karasuma, but, given the extent to which this guy is introverted, given his odd tastes and odd habits, it's hard to imagine this odd ball in a relationship with any other human being. Kenji Harima is the school's feared rebel, but, his infatuation with Tenma matches hers for Karasuma. As Tenma makes a fool out of herself trying to win the affections of Karasuma, who merely seems interested in eating and staring blankly and Harima makes a fool of himself trying to chivalrously win the affections of a largely unacknowledging Tenma, other characters exert parallel (or perpendicular) efforts with similar levels of success. For example, one of Tenma's classmates who has fallen for Yakumo, but also grew up training in martial arts with Mikoto, one of Tenma's circle of girlfriends. In his case, his efforts are thwarted by Yakumo's strict interest in protecting her sister.The outright jokes are rarely the high point of School Rumble. Whether it is linguistic gags, cultural ironies, or traditional references, School Rumble is packed with attempts at humor that are very Japanese. Some of these are amusing regardless. Tenma standing in front of the TV screen punching the air in time to her favorite samurai chambara serial is still grin-worthy if you didn't grow up watching that type of TV show. More often, even when the jokes are understandable, such as the word for rain coat being homonym for kappa-water goblin, they feel dropped on top of the situation. Similarly, there are cases where the physical humor suddenly careens into a situation that is outrageous enough to be laugh out loud funny, but, more often that approach pales in comparison to more decidedly manic, absurd comedies. This soft impact is further cushioned by the anime's slow meter. While the manga is punctuated by short chapters, the anime's rolling continuity between situations leaves a far gentler impression. While Studio Comet hasn't animated School Rumble badly, the targets for their efforts are oddly chosen. A brief cut to a train might employ a nice model and a vision of Tenma spiraling through the water might have an interesting disembodied quality to the effect, but the muted color scheme and use of static elements makes even the fiery Harima seem a bit distant and faded. However, that pacing and the mixed success of the jokes feed into what is really fun about School Rumble. Tenma, Harima and the rest of the cast do things that are strange and frequently futile, but to the characters themselves, their actions makes sense. Even if no one else gets it, for each character, it's all completely logical. A key joke of many shonen romances is the guy accidentally groping the girl, which she reacts too by landing a haymaker on the guy's jaw. Here, it's Karasuma no-selling the fact that Tenma is shooting love-letters at him via bow and arrow, or Tenma missing the self-sacrificing battery of hints that Harima is projecting at her to clue her into the fact that she has forgotten to sign her name on her classroom exam. The idea of radically different wave-lengths is a far more amusing operating concept for an anime comedy than many over-used premises. The lower expectation for the series aids this notion. One has to cheer for the noble, suffering Harima, who works hard, sacrifices and never catches a break. But, unlike the generic hero of a shonen romance, who is always one misstep away from his love, School Rumble does not really concern itself with calling the viewer to feel any real frustration when his efforts are thwarted. Communication failure becomes remains catalyst for the humor rather than an aggravation.

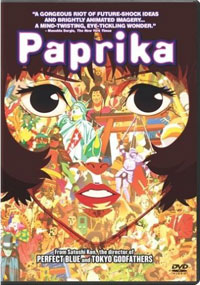

Anime Spotlight: Paprika Reposted from May 1, 2007 Released on DVD and Blu-ray By Sony Pictures today

Satoshi Kon is justifiably considered one the auteurs of anime, and his study of dreams, Paprika, is sure to reenforce that reputation. The movie is an animated triumph, and anyone who appreciates the medium should make it a point to see what Kon's imagination and study of the human subconscious has produced. Kon's work in animation has never been so creative or gorgeous, but the ideas at work in the film don't necessarily have the resonance of his previous efforts. Paprika might not be a Lynchian "what the hell did I just see" experience, but is also not an accessible gateway to the potential of the medium the way Madhouse's sibling movie The Girl Who Leapt Through Time might be. Rather than build off a strong connection with the characters, the reaction is likely to be one of disquiet. Kon's previous films inherited easily navigable roadmaps from the types of stories that they mirrored, whether they were thrillers, holiday feel-goods, procedurals or biographies. Given Kon's trademark attention to the nature of identity, those narratives proved mutable based on the perceptions of their subjects. But, Paprika is directly dream driven. There is a McGuffin, but its pursuit is often convoluted by associative diversions. The events are in no way difficult to follow, even as the protagonists stumble on planted warnings disguised as clues, but there is little certainty to the implications. There is depth and tenderness to the handling of the characters, but often the secondary individuals who shape the events seem like types. The narrative does reach a critical point when an affront forces an emotional reaction. The upsetting barb in the plot seems designed to be acutely provocative. It gives rise to questions, as Kon's works inevitably do, but not personal empathy. This observational detachment is exacerbated by the difficulty divorcing the experience from the craft. While the right brain is taken by the art, the left dissects the images. Even as the film is engulfed by a dream Wonderland, noticing the magic of the creation and motion on screen dominates any personal connection to what is depicted. When it arrived in North America in 1999, Satoshi Kon's Hitchcockian thriller Perfect Blue immediately began raising eyebrows. More often than not, viewers seemed not to know what to make of the story of a pop idol singer who decided to transition into the role of a serious actress, becoming the target of stockers and losing her personal sense of identity in the process. Satoshi Kon's less-idealized character designs lent the work the immediate impression of reality, but the nature of the medium itself still allowed him to blur the line between the concrete factual and the altered perception of the characters. Anime fans may have been ready for that and accustomed to challenging a sense of identity, but Kon still managed to architect a landscape with few firm footholds. Given that there was a sense of reality to its characters, the sexual violence of the movie, the movie's early look at an emergence of a widely read internet and the lack of the solid narrative judgement on the characters' decisions, made Perfect Blue a movie that provoked more questions than definitive opinions. Kon re-engages many of these ideas, including the role of the internet in one's subconscious, for Paprika. As with fellow Madhouse Studios production The Girl Who Left Through Time, Paprika adapts the prose work of Yasutaka Tsutsui. Many Tsutsui stories concern an intrusion of dream logic that highlights the disfunctions of the modern condition. The sensibilities that Kon exhibited in works such as Perfect Blue and Paranoia Agent could not find a better match than Tsutsui, whose short story collection Salmonella Men on Planet Porno is now available in English. Paprika rests on a Philip K. Dick style sci-fi conceit. The DC Mini is a cutting edge technology on the verge of revolutionizing psychotherapy. The device allows an operator to view, record and even enter the dreams of a patient. Unfortunately, the project is severely jeopardized when the units are stolen by what the research foundation labels as a terrorist effort with an inside connection. The crisis becomes critical when the project's overseer, Dr Shima begins spouting nonsense, "Even the five court ladies dance in sync to the frog's flute and drum. The whirlwind of recycled paper was a sight to see..." before jumping out of a fifth story window, in what is quickly diagnosed to be a case of dreams being projected into the minds of one who has previously connected to the DC Mini. Doctor Atsuko Chiba assumes charge in tracking down the missing devices, which have already been condemned as a moral affront and symptom of the arrogance of humanity by the foundation's frail, wheel chair bound chairman. At the same time, she minds the device's morbidly obese inventor, Dr Tokita, trying to get the boyish genius to take responsibility for his creation. Detective Konakawa, still recovering from an anxiety disorder, becomes entangled with the investigation through his connection to the mystery-woman Paprika. Dr Chiba is a pale, constrained woman, marked by insistent formality, tied hair, and conservative dress. This is not an especially effective Clark Kent disguise for her Paprika dream-therapist alter ego. Anyone who knows of both at least suspects that they are one and the same. Stellar Voice work is a key feature of how the movie functions. The cast is filled with highly respected voice actors, including Kouichi Yamadera (Cowboy Bebop's Spike Spiegel, Ghost in the Shell's Togusa), the heavy voiced Akio Ohtsuka (Ghost in the Shell's Batou) as Konakawa and Tohru Furuya best known as the near autistic boy genius pilot Amuro Ray in the original Gundam as Tokita (but also Sailor Moon's Tuxedo Mask, Saint Seiya's Pegasus and Dragon Ball's Yamcha). Dr Chiba/Paprika is voice by the queen of anime voices throughout the 90's, Megumi Hayashibara, whose work includes female Ranma, Slayer's Lina Inverse, the then against-type role of Rei in Neon Genesis Evangelion, Jessie/Musashi in Pokemon and Faye Valentine in Cowboy Bebop. As Dr Chiba, Hayashibara puts on a real performance as a character who intends to talk in measured tones, but who can become upset, rant, lose spirit, or express great care. As Paprika, Hayashibara is in classic anime character mode. Her exaggerated, high tones fit a wise attitude onto a cute demeanor. If you think of the kind of anime character you'd see on a poster or t-shirt, this is the kind of voice that would be attached to that image. The Paprika character herself is a living pop culture artifact. When sitting still, she takes on her role of therapist, asking probing questions in hopes of revealing the root cause for her patient's troubles, but as the movie's music video like opening credits depicts, her spirit is that of a iconic logo or spokesperson. In jeans and casual shirt, she skips through the city, hopping through billboards, t-shirts, computer screens and the like. She even moves like an idea. While Dr Chiba takes off her shoes, pumps and her arms and runs like a person trying to push their body into their rush, Paprika keeps her elbows stationary like a cartoon schoolgirl when running. Her comfortable ease extends to scenes of acute danger. Confronted face to face in the dream world, she nimbly hops to the side. It's obvious why her troubled patients have little conscious reservation sitting down and talking to her. There's an instant likable to that kind of cool, but even when she does have a sharp quip, she seems entirely unchallenging. Through Tokita's habit creating more DC Mini's rather than face trouble, there is commentary on geek escapism within the movie. However, given that characters respect Paprika rather than fall hard for her, it would seem that the thrust of Kon's message for the movie has little to do with anime fans specifically. Slipping in and out of the subconscious, Paprika proves to be the ideal scalpel for cutting into dreams. Trying to piece together the meaning and language of dreams proves to be a lot like looking into movies. Kon gets into the act to the point of including billboards from his previous works. As Paprika explains to Konakawa, REM dreams are longer, easier to analyze due to their similarities to full length block busters, where as the dreams of earlier sleep periods have the qualities of short artsy films. It's almost obvious that this would be a fertile field for Kon. The nature of dreams intersects with animation in that imagination becomes indistinguishable from reality. This can be as subtle as a strange way of water beading off a windshield. Seeing it in Paprika, one has to wonder whether it is an unusual condition or a factor of a dream experience. Magnified, there is a freedom of associative transition that yields disturbingly confrontational images. The movie's prologue quickly tests ability for thought to turn malignant as Konakawa is rushed by a crowd where every assailant has his own face. The ramblings of Dr Shima referred to a procession of images that leaves an indelible impression throughout its appearances during the film. Kon accumulates an avalanche that convincing could drive people to jump out of windows. This rummage bin of the subconscious calls to mind a famous "monster parade" scene from Pom Poko, an environment talking animals fable from Ghibli's second great director Isao Takahata. The movie follows two clans of tanuki, a mammal frequently described to non-Japanese natives as a "raccoon dog." One of the abilities that legends ascribed to the animals is shape shifting. For their grand effort to halt the destruction of their habitat, Pom Poko's tanuki stage a massive parade of monsters. A spectacle pours forth as the tanuki adopt the shape of various yokai from traditional folklore. Despite the sci-fi nature of the DC Mini, the images employed suggests that the concerns being explored are not future speculations or even specifically modern. Unlike Paprika herself, these seem cumulative rather than products of the current zeitgeist. Paprika becomes adjusted into fantasy guises for excursion into this territory, becoming the monkey king Son Goku, the sphinx, Pinocchio of the like. There is a specific bawdy chorus line in when cell phone headed men in business suits look up the skirts of cell phoned headed teen schoolgirls, and dancing appliances play a prominent role in the parade, but the bulk of the crowd is filled with an absurdist flip on more long standing images. Traditional good luck charms spring around as Japanese temple arcs march with the Statue Of Liberty. Christian and Buddhist icons with undergarments laid over the statues file along together. A scene as simple as Dr Chiba walking or driving can be entrancing given what its minutia says about the character. Watching her posture, the direction of her eyes and how she physically presents her rhetoric in a, pardon the pun, animated conversation is a marvel. When that precise care is turned to convulsing masses of dream figments, the movie moves into masterpiece territory. Design meshes perfectly with the quantity and complexity of motion. For example, Tinkerbell-Paprika's evasive flight is as good as any aerial animation. The environments, structures and creatures of Kon's dream world becomes as well realized as any fantasy kingdom of any moving media. These experiences are etched into memory in no small part thanks to the contribution of electropop musician Susumu Hirasawa, who previously worked with Kon on Paranoia Agent and Millennium Actress. Anime fans might also know the artist from his work on Berserk. The distortion of layered babel chants rest on his march beat for a disturbingly catchy tune. You can't take your eyes of Kon's visuals, but it is Hirasawa that gives the experience its sense of infectious mania. Within its narrative story, Pom Poko's monster parade did not achieve its desired results. The onlookers marveled at the spectacle, puzzled on its origin, and ultimately pushed forward building a housing development on the tanuki's homeland. Scenes of Paprika are deeply effecting, and there is plenty of room for consideration, but it does not force any reevaluations. Dr Chiba's reactions are believable. Konakawa's troubles are intriguing and well developed. Unfortunately, it is too easy to disregard the antagonists as works of fiction, present simply to exacerbate trouble. Their agenda and behavior is the stuff of nightmares, but nightmares that an adult would have no trouble shaking off. Unlike most anime works, even the majority of mature minded ones, Paprika concerns people who are already entrenched in careers. As such, the ambiguity to the deeper implications of the movies events seems to stem from the fact that existential considerations aren't at the forefront of these characters' thoughts. Concerns about what was left behind and how the current point has been reach become funneled through the subconscious. Even with the root causes revealed, it's back to dream image interpretation to unravel the whole story. The the same time, Paprika actively resists imparting well packaged lessons. Tsutsui short stories have an air of creatively expressing deep dissatisfaction through gritted teeth. They can take the form of an apocalyptic rant made under ones breath. Kon's Paprika has tendencies in that direction, but it isn't nearly as caustic or as direct. It doesn't explicitly indict anything. The mentions of terrorism work into a trend where the speeches that offer preaching sermons are points where red flags call for a skeptical approach.