Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Logo handmade by Bannister

Column by Scott Green

Surveying the prominent genres that are represented in anime and manga translated for North American audiences, horror notably stands apart in a unique niche. It is consistently present in the market, and consistently struggling. Furthermore, the field is often diluted. You'll find works that are not especially good or not especially horror. Horror manga is a rich tradition that is home to some outstanding creators, but there is little room for blanket statements concerning the genre. The difference is not just the sharp divides between categories such as gothic or splatter or folklore. There is a solid individuality to be found in specific creators and specific work. Even if you appreciate the baroque gruesomeness of Junji Ito's work, the pus covered, decaying morbidity of Hideshi Hino's works may or may not be to your liking. Yet, as distinct as a Ito's psyche-cracked, hyper rendered flesh is from Hino's congenitally defective cartoons, both are creators worthy of recognition, and both utilize the specific style with the qualities of their medium to devastating effect. In cases such as these, horror manga both demands and rewards close attention. In the case of anime, without splitting hairs and calling works like Serial Experiments Lain or Satashi Kon's Perfect Blue "horror", there are few unqualified successes to point out. There are, however, an abundance of piece-mail points of interest from the unforgettably mournful opening of Curse of the Undead Yoma to the violence of the infamous Urotsukidoji. The more prominent trouble is that in anime, the trappings of horror are frequently appropriated as garnish for another genre: vampire action, vampire romance, vampire comedy to name a few. The blockbusters in anime and manga have been serials, and the essential trait of successful horror is antithetical to the trait of successful anime/manga. Any given serial needs to confound expectations from time to time, but it also relies on predictability. Line up 30 giant robot anime, 30 fighting anime, or, it may be harder to do with English language releases, line up 30 sports anime and predictable, anticipated patterns will be at the core of the appeal. Horror adheres to patterns as well. The same urban legends, folklore and Kabuki plays are reused throughout the genre. But, in the case of horror, there is a sharper reliance on a swerve to the presumed premise. Ultimately, the observer needs to be thrown off balance. Especially if the work is not simply ticking down to some gore bomb (see the Saw box office), it should be leaving the consumer uneasy and disoriented. Anime and manga are full of classic tragic endings, but knowing that you are being set up for a fall in horror makes the reception different from something like Neon Genesis Evangelion or the boxing serial Ashita no Joe. In theory, it should not work if you are seeing the same thing again and again. Desensitization kills the genre, because the viewer knows attack that some attack is coming from the onset. This divergent appeal has proven to be a commercial liability for horror. History has suggested the work needs to be marketed to consumer who are not typically inclined towards anime or manga. Anime fans have long sighted unique visual presentation as a key point of attraction to the medium, but they did not exactly flock to Requiem from the Darkness, an anthology work about a Grimm-esque story gatherer wandering a landscape of Edo era Japan depicted through abstract dream images. Cult cinema fans might have embraced its giallo-like palette, but probably would not have known to look for the anime. Anecdotally, the most vocal supporters of Viz's release of Junji Ito's Uzumaki were more frequently readers of American comics rather than manga. However, casting a wider net has its own, equally severe, concerns. Choice in the field works against the market for horror anime and manga. Teen action serials that approach the quality of Naruto are in short supply. On the other hand, horror fan can sample the output of Hollywood, generally a few TV series, book shelves worth of prose, North American comics, and video games. Consequently, the consumer dollar is greatly diffused before reaching the manga shelf. Under that grand pressure, ambitious projects have an unfortunate history of fading quickly. The genre itself presents a compelling challenge to make sense of. Ordered by anticipated sales, then shortened by flagging ones, the jumbled lineage of horror anime and manga represents a jigsaw puzzle for enthusiasts. From the perspective of a North American observer, it is as if chaos has ruled in dictating who releases what, when. TOKYOPOP released Parasyte before the manga boom, when the company was still called Mixx. Eight years later, Del Rey is releasing it. Uzumaki was published by Viz as apart of their alternative anthology Pulp and its creator Junji Ito became synonymous with horror manga to North American reader. Pulp goes away, but Viz releases his fishy two volume work Gyo, and Orochi: Blood, a single volume of work by one of Ito's chief inspirations, Kazuo Umezu. Later, Dark Horse started releasing an anthology of Umezu work, and Ito's work from the beginning, starting with his Tomoe stories, which had themselves been previously published in North America by the defunct ComicsOne label. Dark Horse then halts Umezu and Ito, but Viz continues releasing Umezu's classic Drifting Classroom, and schedules new printings of Uzumaki and Gyo. A reason to sample horror and latch on to the best is that, in the face of media saturation, when horror media works, it really works. Flash animation of stick figures throwing punches can be exciting, but when a story disconcerts the observer or produces anxiety, it becomes a testimony for the power of its medium. Turning a page of one of Rumiko Takahashi's flesh-eating Mermaid stories and being confronted by a simple, yet striking image is a demonstration of the dictated pacing a skilled creator can accomplish with the flow of panels and pages in a comic: how all of a sudden the reader can be forced into a dead stop by a staggering image.

Anime Spotlight: Demon Prince Enma Volume 1 Released by Bandai Visual

Cuteness is relative when considering the world of Go Nagai. The anime version of Dororon Enma-Kun opened with the flaming crags of hell, and kiddy vocals singing as the bratty hero sticks out his tongue at the realm's overlord. That isn't half as creepy as the ending theme, which features a squad of ink-blot spirits slinking through photographs of keyholes, phones, the eyes of dolls, discarded shoes, manhole covers and the like, set to rustic music. The 2006 direct to video OVA was not exactly taking an innocent children's property and making it a blood and sex adult fair. It was taking a strange mid-range popularity work from a creator that the PTA loathed, and making its characters horny young professionals. Enma is a demon prince with the power of hell fire who is recognizable from his flame like orange hair, and his strange witch's hat. The adornment is actually a frequently sleeping, elderly demon named Grandpa Chapeauji. His opposites-attract companion is the kimino clad ice princess Yukihime. Given that this demon royalty apparently has not spent much time in the human world lately, they rely on Kapauru, a dirty old man kappa (water/turtle spirit) who has been hiding in plain sight as the "costumed" marketer for a cabaret club. Part of the fun of this older take on the characters is that not only are they sexualized, they are crazy in the manner of professional athletes or Paris Hilton celebutantes. Not only are they clueless, they're oblivious. Yukihime is haughty, but Enma takes the obnoxious hot head character type to a new level. Interacting with the pair would probably be far from fun, but there is a magnetism to watching the behavior of unabashedly unpleasant people. What they are doing in Japan looks a lot like solving supernatural mysteries, but for these hunters, the victims of wandering monsters are, at best, clues. If the target is already located, the suffering humans are irreverent. Enma and company are simply present to track down rogue demons and give the monsters the option of servitude or death. In keeping with the darker mood, rather than act buoyantly in their self importance, Enma and Yukihime sneer at the work. There is a hollow humor to this detached obnoxiousness. No well made Go Nagai adaptation should be humorless, but in this case, the subtext is that there is nobody looking out for the ill-prepared humanity. The first two episode volume is composed of a pair of standalone episodes as Enma and Yukihime track down Nobusuma: Rot-Pus Suck Demon and Piguma: Corpseless Demon. Both reference familiar horror standards, both in call-backs such as Poltergeist buzzing TVs and in the stories' premises. The first is an incest themed vampire story. The second is the story of a young woman with her life crashing down, who begins to see a doll killing the people who angered her. Even if the final act twists are obvious, the unusual nature of the demon hunters involved and the notion that even trying to overcome human frailty, these victims were still susceptible to falling under the influence of darker forces give the series a disconcerting edge. Driven by Elfen Lied director Mamoru Kanbe and writer Takao Yoshioka, the horror mysteries evolve into cute chick bloodbaths. The creative pair gained notoriety in North America for a televised anime series in which people where vivisected, their heads were twisted off, and the camera was given a close look at the cross-section as fingers or limbs were cut off. Enma's violence is frequently quick rather than lingering, but it is vicious and it is given the further leeway of an OVA release. Given the license granted by Go Nagai's name attached to a project, it is hard to be taken aback by tasteless lack of restraint. When Elfen Lied featured a mind addled young woman wetting herself, it seemed poorly conceived. When Demon Prince Enma showcases a stream of blood traveling up the intimate area of a young woman as she bathes, it is at least in the spirit of the venture. Demon Prince Enma falls into the category of "general appeal", if you take the term to mean young men who will pack movie theatres to see bloody horror. Enma's distributor packages their titles for dedicated anime consumers, meaning that the Japanese audio only DVD retails for $39.98. Neither the original manga nor its early TV series have been available in English, but unfamiliarity with the characters is a gap that casual viewers could bridge just as easily as more frequent anime consumers. Stellar sales for the less than stellar animated Lady Death feature demonstrated that there is a solid level of interest for T&A and blood animation. Unfortunately, the price point and packaging of Demon Prince Enma makes the title easy to pass up.

Manga Spotlight: Drifting Classroom Volumes 5 and 6 By Kazuo Umezu Released by Viz

As an older manga reader, The Drifting Classroom is a thrilling example of horror manga as gonzo social commentary. Yet, again and again, it inspires jealousy for anyone lucky enough to read the work at the impressionable age of 12. With violence that is more explicit and more pervasive than a Paul Verhoeven film, the "parental advisory: explicit content" warning is inarguably valid, but its look at social dynamics in a crisis and the inclusion of all sorts of people completely losing their composure had to have been entirely mind-blowing for young readers. Through Drifting Classroom, Kazuo Umezu presents an impish showcase of human nature. The manga calls to mind Osamu Tezuka's approach at looking at patterns of behavior under extreme circumstances. However, instead of the compassion that Tezuka seeded into his work, Umezu demonstrates a bemused hope that the natural condition of savageness can be righted through struggle. Murderous violence might blanket the work, but there is also a positive regard for rebellious people trying to set a better course. The manga has the feel of Lord of the Flies as presented by a bus load of screaming children mid-fall after a plunge off a cliff. Some readers have criticized the manga for being comprised entirely in the constant state of panic. This prompts the joking speculation on the range of emotions that Umezu might be capable of capturing in his manga. Except, that the tone is evidently intentional. There is a telling page that just shows cars traveling through a city corner, oblivious to the ends of the manga. In the same way that all of the characters are running and screaming, every car is speeding along, emitting exhaust, dust and a loud "vroom". Even outside the life and death struggle of the children, everything in the world of The Drifting Classroom is engulfed in a frayed panic. Volume 5 of Drifting Classroom recommences from the previous volume's cliff hanger: a primary school building, full of children is transported into the far future, and facing the latest threat, the children panic as a swarm of crawling insect begin eating them to the bone. As one child is devoured, he reaches out to grab the next, where-by the crawlies are transferred through the herd. As one child is reduced to exposed skeletons and pieces of flesh, it is almost as disturbing to see other students fall and be trampled. As over used and diluted as the adjective "extreme" might be, it is a valid description for Drifting Classroom. Film tends to be thought of as the primary popular visual medium for horror, but, if you are keeping a score card for memorable scenes, each volume of Drifting Classroom offers at least a couple that deserve to rank up the list with Zombi 2's eye or Texas Chainsaw Massacre's finger prick. In part, that is because Kazuo Umezu is using children. Watching unthinkable things happen to kids is effecting on a different level than watching teens or adult suffering the consequences of their decisions, That's not because these children are innocent angels, they are capable of vile actions against each other, but because, at least in theory, they aren't as hardened and equipped to deal with situations the way an adult would be. The other component of the horror's "extreme" nature is Kazuo Umezu's clever and unrelenting commitment to the awful. If a toddler is desperately calling for attention, Umezu puts the child in a boarded up building. Speadlines radiate from the glass as the child thumps on the pane. Inked with a solid stream of striation lines against the flow of the force marks, the child is vissibly stressing his surroundings. The fears of the moment are realized as the glass shatters outwards, gashing the child's hand. This might be more minor than the impalements or clubbings, but it demonstrates how Umezu's approach attacks on both ends of a painful event. He builds the anticipation for the crucial moment, then delivers on the awful truth that is as bad or worse than the imagined consequence. Volume 5 continues to view the tribulations of Drifting Classroom as a microcosm akin to a social simulation on fast forward. Previous conflicts lead to the founding a new society lead by a group of trouble makers and geeks from among the school's older children. As the mob panic and trampling of the insect attack demonstrated, there is still a tension between addressing problems as a social organization and the impulse of self preservation. When this group begins determining how sustainable the available food and water might be, there is a false sense that Umezu is establishing something static. While panic persists at a fever pitch throughout the manga, Umezu ensures that it does not settle into a monotonous progression of screaming faces. While the characters' reactions are always credible, the continually shifting social and environmental landscape makes predicting the next cause of woe impossible. The ferocity with which Umezu knocks over the structure he just built is stunning. Having established some social order, the violence that erupts becomes more sophisticated than just chaos or pack mentality jostling for power. Set off by a plague scare, the cascade of events paves the way for quarantine, coups, civil war and purges. The manga has previously employed the device of a parent in the present going to dire measures to help the future-stranded children. Volume 6 is largely comprised of a longer, repeat exercise. Read at age 12, this would be explosive. It's one thing to see children attack other when trapped in a deadly wilderness, but regardless of how terrible terrible the prospect of losing a child might be, seeing house wives go MMA on each other is on a whole other level. In a mundane context, applied to adults, the level of screaming and violent reactions doesnít seem nearly as plausible. This reaches its height with a component story of a professional baseball player who has a role to fulfill in saving the children. The Umezu-logic at work is characterized by its shaggy dog convolution, people punching each other in the streets as only he or Gundam's Yoshiyuki Tomino could imagine, and a lot of stabbing. Whatever faith one might have in Umezu and whatever intensions one might go into the manga with, this is difficult to take seriously. Umezu seems to come to this craziness honestly, but this does not look intentionally funny. At best, if you can appreciate it as seriously made, but zany cult media, you can at laugh this without it detracting from the rest of the manga's hysteria.

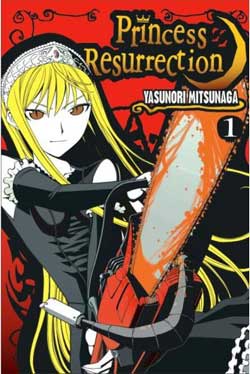

Manga Spotlight: Princess Resurrection By Yasunori Mitsunaga Volume 1 Released by Del Rey

If you've been following anime/manga for a while, you may have heard this one before. A supernatural maiden accidentally tramples a typical teenage guy while he was crossing the street. Feeling a bit bad about killing the young man, she revives him to become her immortal servent. That was the concept for Yuzo Takada's (All Purpose Cultural Cat Girl Nuku Nuku, Blue Seed) grizzly horror action 3x3 Eyes, and it gets revived for the more fashion conscious Princess Resurrection. The manga opens with Hiro dead in a hospital morgue, with a white cloth draped over his face. While the manga launches from a location that suggests modern Japanese horror, with airs of a traditional tableau, the manga's is creature population is unmistakably Western, and, with vampires, wolfmen (and girls), invisible men, electrically animated people and fish-people, it looks specifically influenced by the Universal Monsters. As Hiro lies dead, a young woman appears. What is most notable about this figure is her loligoth attire: lace fringed black dress, black leggings and long gloves, even a tiara. She sinks a fang into her finger, then lets the blood dribble onto Hiro's face. There is a quick flash back to Hiro's Death. He's on his way to the giant mansion on a hill where is older sister is to be employed as a live-in maid. Walking down the street, a van is suddently sent through the air, onto him. It turns out the van was launched by a short girl in a black and white maid's dress who had been pulling a cart with a comically large mountain of antique furniture. The aforementioned loligoth jumps down from the top of the cart and remarks "it's a good corpse." With his new lease on un-life, Hiro turns up at his sister's place of employment, and finds the loligoth girl brandishing a rapier and the short cart-puller holding up an entire tree. The pair is about to fight a Jon Talbain-esque werewolf and his pack of dogs. Hiro finds himself aiding the pair, receiving another lethal wound in the process. When itís all said and done, and Hiro and the werewolf are lying in pools of blood, the loligoth girl introduces herself as "Hime" (princess), "daughter of the king who stands above all monsters." So, Hiro, along with his large chested, maybe not so bright sister, and the little, super strong maid-creature, who can only say "hooba" and a few other cute monster people all end up working for Hime in her mansion. You can judge Princess Resurrection by its cover. It might borrow from a range of horror tropes, but it rarely treats any with a straight face. It does have the structure of a non-descript guy who is under the sway of a girl, but little has suggested that the typically accompanying romance will play a prominent role in the manga. Part of the appeal is the look of an exotic, nonplussed girl assaulting monster with deadly weapons, such as chainsaws, swords, battle axes or crossbows. It is Buffy the Vampire Slayer taken to comic absurdity: snobby girl in delicate fashion up to her elbows in blood. The naughty impression of a proper looking, or at least flamboyantly dressed princess getting her hands dirty does not wear out over the course of the volume, and the black and white fashion plays especially nicely in the similarly black and white manga. The other half of the appeal is watching the violence visited upon Hiro. As 3x3 Eyes did, Princess Resurrection takes advantage of its hero's living dead state to find impressively graphic ways of damaging the lead. Given the contract with the reader, that the violence inflicted on the character does not really matter, here's a level of Itchy and Scratchy sadistic mirth seeing the character's wide eyed loss of composure as he witness his own blood spilled. Not every joke is based around stab wounds or drowning. The manga also offers sight humor built around slightly modified versions of classic monsters and the goofiness of creatures from the Black Lagoon banging on drums and dancing around a bonfire is at least smirk-worthy. However, the most memorable bits are the pain gags, such as Hiro noticing that something is wrong after walking through cutting wires, then looking back with dismay to see that he has shed a foot and some limbs. The manga is sufficiently cartoonish, that it doesn't suggest any guilt in chuckling at Hiro's woes.